Lung Ultrasound is an accessible, low-cost technique that has demonstrated its usefulness in the prognostic stratification of COVID-19 patients. In addition, according to previous studies, it can guide us towards the potential aetiology, especially in epidemic situations such as the current one.

Patients and methods40 patients were prospectively recruited, 30 with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and 10 with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). The patients included underwent both a chest X-ray and ultrasound.

ResultsThere were no differences in the 2 groups in terms of clinical and laboratory characteristics. The main ultrasound findings in the SARS-CoV-2 group were the presence of confluent B lines and subpleural consolidations and hepatinization in the CAP group. Pleural effusion was more frequent in the CAP group. There were no normal lung ultrasound exams. Analysis of the area under the curve (AUC) curves showed an area under the curve for Lung Ultrasound of 89.2% (95% CI: 75%.0–100%, p < .001) in the identification of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. The cut-off value for the lung score of 10 had a sensitivity of 93.3% and a specificity of 80.0% (p < .001).

DiscussionThe combination of the findings of the Lung Ultrasound, with a Lung Score greater than 10, added to the rest of the additional tests, can be an excellent tool to predict the aetiology of the pneumonia.

La Ecografía Pulmonar es una técnica accesible, de bajo costo y que ha demostrado su utilidad en la estratificación pronostica en pacientes con COVID-19. Además, según estudios previos, nos puede orientar hacia la potencial etiología, especialmente en situaciones epidémicas como la actual.

Pacientes y métodosSe reclutaron prospectivamente 40 pacientes, 30 con neumonía por SARS-CoV-2 y 10 por neumonía adquirida en la comunidad (NAC). A los pacientes incluidos, se les realizó tanto una radiografía como ecografía de tórax.

ResultadosNo hubo diferencias en los 2 grupos en cuanto a las características clínicas y analíticas. Los principales hallazgos ecográficos fueron en el grupo de SARS-CoV-2 la presencia de líneas B confluyentes y consolidaciones subpleurales y la hepatinización en el grupo de NAC. El derrame pleural fue más frecuente en el grupo de NAC. En ningún caso la ecografía pulmonar fue normal. El análisis de las curvas ROC mostró un área bajo la curva para la Ecografía Pulmonar del 89,2% (IC 95%: 75,0–100%, p < 0,001) en la identificación de la neumonía por SARS-CoV-2. El valor de corte para la puntuación del puntaje pulmonar de 10 tuvo una sensibilidad del 93.3% y especificidad del 800% (p < 0,001).

DiscusiónLa combinación de los hallazgos de la Ecografía Pulmonar, con un puntaje pulmonar mayor de 10, complementando el resto de las pruebas complementarias, puede ser una excelente herramienta para predecir la etiología de la neumonía.

Twelve months after the declaration of the pandemic due to the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19), with more than 115 million confirmed cases worldwide,1 new tools continue to be explored to improve diagnostic and treatment protocols to avoid further system collapse.2

Community acquired pneumonia (CAP) is one of the most common pathologies within respiratory tract respiratory infections, treated in the hospital emergency departments (HED). Given its high rate and potential severity, imaging modalities are required to facilitate safe and rapid patient assessment.

This fact has increased the need for an accessible diagnostic method, low in cost, and easy to use tool for the early classification of risk in patients with COVID-19, which will also direct us to the potential aetiology, especially in future epidemic situations.3,4

Lung ultrasound is the best tool for this proposal, providing us with an evidence-based method to help classify patients according to their risk of presenting with complications5,6 or sequelae.7 It is innocuous, fast and widely available, useful in different vulnerable populations (e.g. pregnant women, paediatric ages, the elderly, intubated patients) and different areas (homes, nursing home or out-of-hospital emergency), complementing other imaging techniques, such as chest X-ray and computed tomography.8

We conducted this study to determine the impact of lung ultrasound to distinguish pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2 compared with other aetiologies during the current pandemic situation.

Patients and methodsA prospective study conducted in the HED of an academic hospital, undertaken in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of our centre. Informed consent was obtained from each patient recruited.

Patient selectionWe included patients attending the HED and whose reason for hospital admission was a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia (clinically compatible and positive RT-PCR test) and patients with CAP of other aetiology (compatible chest X-ray, at least 2 negative RT-PCR tests and satisfactory response to antibiotic treatment).

A convenience sample of patients meeting these inclusion criteria was selected according to the availability of the principal investigator. Patients were followed up during the following week of hospitalisation.

Initial patient assessmentInitial patient assessment included collection of clinical data, physical examination (temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation), chest X-ray and analysis (haemogram, glucose, ions, kidney function, liver enzymes, lactate dehydrogenase, ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP), coagulation and D-dimer).

Ultrasound data collectedAn internist with extensive experience in thoracic ultrasound (according to American College of Emergency Physicians criteria)9 performed all examinations using a GE VENUE cart ultrasound machine equipped with a curvilinear probe (1.5–4.5 MHz) (General Electrics Healthcare, Madrid, Spain) as a pocket device, a Butterfly IQ (Butterfly Network, Guilford, CT, USA).

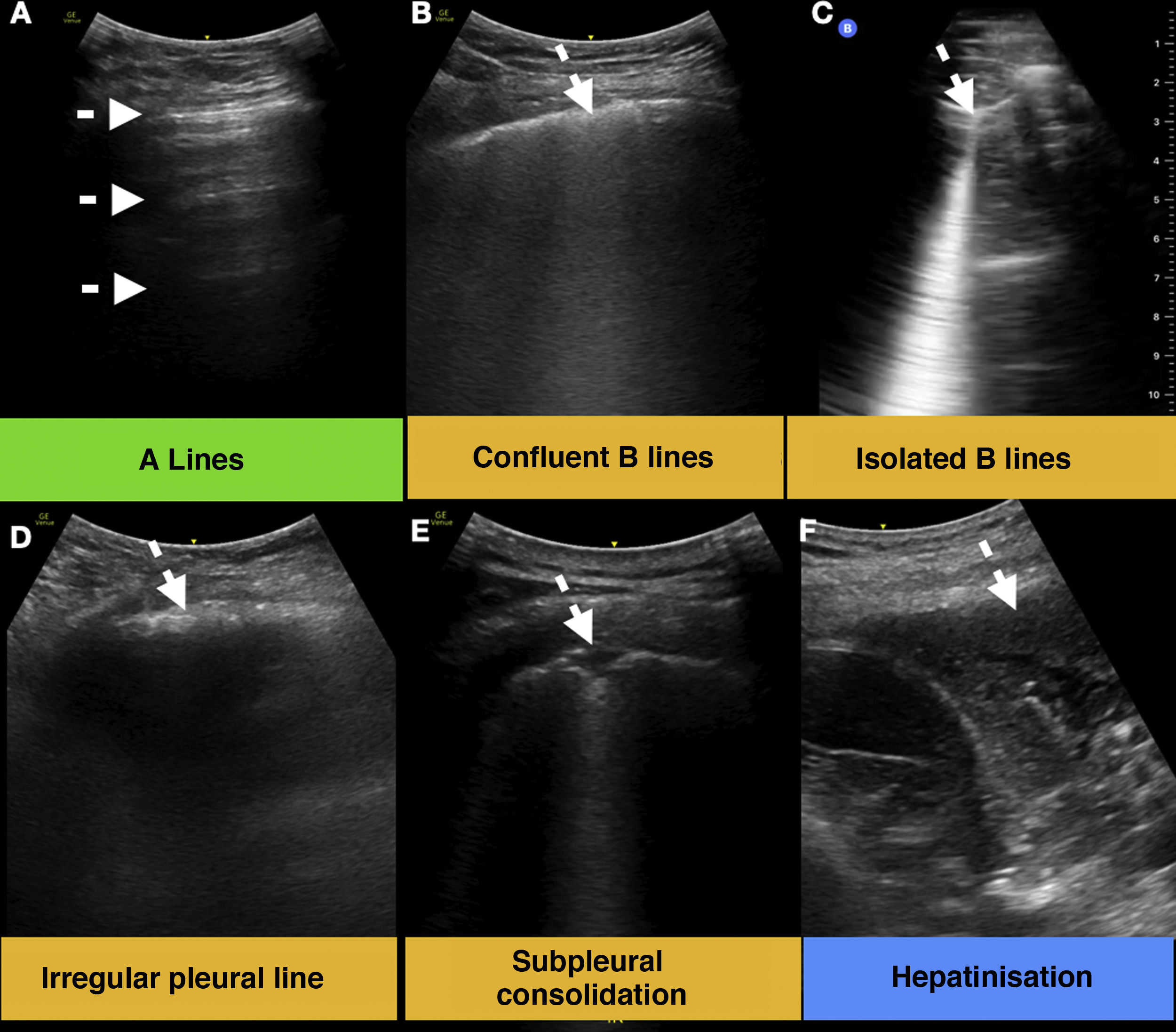

Lung ultrasound was performed with the patient in 60 and lateral decubitus, following a 12-zone protocol 5−6. Each intercostal space (probe parallel to the space, avoiding costal shadows) of the upper and lower parts of the anterior, lateral and posterior regions of the left and right chest wall was carefully examined. In each area, the following ultrasound findings were recorded (Fig. 1):

- -

A-lines, score of 0; isolated B-lines or irregular pleural line, score of 1; confluent B-lines, score of 2; subpleural consolidation or hepatinisation, score of 3.

- -

Adding the highest scoring finding in each area, we obtain the lung score with values between 0 and 36 (maximum value per area 3, for 12 areas in total).

The studies were performed in ignorance of the patient's personal history, vital signs, laboratory results and therapy.

The main objective of this study was to describe and characterise lung ultrasound findings in patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia versus CAP of other aetiologies in patients admitted to the emergency department.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were expressed as absolute value and percentage, quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation (SD). For comparisons between groups, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for qualitative variables and Student’s t-test for quantitative variables. Statistical significance was set at p-value < .05. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS v25.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsA total of 40 patients, 30 with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and 10 with CAP of other aetiologies, were included between December and January 2021 (summarised in Table 1). Of the patients with CAP with a filial aetiology, four had pneumococcal pneumonia and one had gram-negative pneumonia. There were no differences in the 2 groups in demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics, except for a higher presence of tachypnoea in the SARS-CoV-2 group and leukocytosis in the CAP group. The main treatment in the SARS-CoV-2 group was corticosteroids (dexamethasone 6 mg/d) versus antibiotherapy in the CAP group, all patients in both groups took at least antithrombotic prophylaxis.

Demographic, clinical, analytical and radiologic characteristics of patients included in the study (N = 40).

| SARS-CoV-2 (N = 30) | CAP (N = 10) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | |||

| Gender — woman | 17 | 4 | .361 |

| HBP | 12 | 7 | .100 |

| DL | 12 | 2 | .251 |

| DM type 2 | 6 | 2 | 1000 |

| Obesity | 3 | 0 | .535 |

| Smoker | 2 | 3 | .066 |

| Heart disease | 10 | 6 | .136 |

| Pneumopathy (COPD/asthma) | 5 | 4 | .126 |

| ICU admission | 3 | 2 | .482 |

| Physical examination | |||

| Heart rate — lpm (SD) | 79.8 (18.4) | 80.9 (9.3) | .866 |

| Respiratory rate — rpm (SD) | 25.6 (1.1) | 20.7 (2.9) | *.017 |

| Temperature — t° (SD) | 36.1 (1.0) | 36.8 (.9) | .068 |

| Systolic blood pressure — mmHg (SD) | 127.5 (17.8) | 123.7 (18.9) | .572 |

| Oxygen saturation — % (SD) | 92.1 (4.2) | 92.9 (3.2) | .607 |

| Lab results | |||

| Haemoglobin — g/dL (SD) | 13.7 (1.9) | 12.1 (2.6) | .041 |

| Leukocytes — /mL (SD) | 8294 (4572) | 16,757 (20,533) | *.038 |

| Lymphocytes — /mL (SD) | 1238 (519) | 1217 (957) | .928 |

| Dimer D — ng/dL (SD) | 2376 (4269) | 1127 (975) | .369 |

| LDH (SD) | 316 (105) | 389 (182) | .149 |

| GPT — U/L (SD) | 48.1 (30.9) | 27.1 (32.1) | .076 |

| GOT — U/L (SD) | 53.8 (45.8) | 33.1 (27.3) | .190 |

| Creatinine — mg/dL (SD) | .94 (.36) | 1.4 (1.5) | .108 |

| C-reactive protein — g/L (SD) | 88.1 (88.4) | 89.1 (76.2) | .974 |

| Treatment | |||

| Corticoid steroids | 21 | 0 | *<.001 |

| Antibiotic therapy | 16 | 10 | *.007 |

| Intermediate heparin dose | 4 | 0 | *.002 |

| Therapeutic heparin | 4 | 0 | *.002 |

| Chest X-ray | |||

| Normal — (%) | 4 | 0 | .224 |

| Interstitial filter | 26 | 10 | .224 |

| Unilateral | 4 | 6 | *.010 |

| Bilateral | 22 | 4 | *.010 |

| Lung ultrasound | |||

| Normal | 0 | 0 | 1000 |

| Hepatinisatoin | 0 | 7 | *<.001 |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 3 | *.002 |

| Isolated B lines or irregular pleural (affected areas /12 per patient) | 61/360 | 11/120 | *.038 |

| Confluent B lines (affected areas /12 per patient) | 113/360 | 9/120 | *<.001 |

| Subpleural consolidation (affected areas /12 per patient) | 107/360 | 19/120 | *.002 |

CAP: community-acquired pneumonia; SARS-CoV-2: acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SD: standard deviation.

The main ultrasound findings were the presence of widely distributed confluent B-lines and subpleural consolidations (smaller size, generally < 1 cm) in the SARS-CoV-2 group, and hepatinisation (larger consolidations) located in posteroinferior lobes in the CAP group. Pleural effusion was more frequent in the CAP group. In our cohort, in no case was the lung ultrasound normal.

Radiography was pathological in all cases except for 4 patients with SARS-CoV-2. These 4 patients ranged in age from 87 to 89 years, lung ultrasound showed mainly confluent B-lines and subpleural consolidations, with lung scores of 12, 20, 24 and 29, as well as absence of hepatinisation or pleural effusion. The infiltrate in the PDA group was multilobar in 4 patients.

ROC curve analysis showed an area under the curve for the lung score of 89.2% (95% CI: 75.0%–100%, p < .001) in identifying SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. The cut-off value for the lung score of 10 had a sensitivity of 93.3% and specificity of 80.0% (p < .001).

DiscussionIn epidemic situations, as is currently the case in COVID-19, it is essential to have reliable and easily accessible diagnostic tools that can guide us in the diagnosis and management of patients, especially in areas with limited resources. Some studies are beginning to suggest that lung ultrasound may be a first-line diagnostic tool to complement conventional chest radiography and computed tomography.6,8

Lung ultrasound can provide early guidance towards viral aetiology in lower respiratory tract infections by identifying confluent B-lines and bilaterally distributed subpleural consolidations, where the diagnostic accuracy of physical examination and chest radiography is lower.10

Unfortunately, there are few studies on this issue in the adult population; most of them have been performed in the paediatric population. A study during the H1N1 pandemic showed that lung ultrasound was able to distinguish between viral pneumonia (presence of B-lines and subpleural consolidations) and bacterial pneumonia (pulmonary hepatinisation) or the presence of bacterial superinfection bacteriana.3 Similar findings have been observed in adults with H1N1.11

As in our study, we observed that larger consolidations (hepatinisation) and more localised involvement (lower total lung score) are more specific to CAP, as opposed to SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, with subpleural consolidations (smaller size) and more diffuse distribution (higher lung score). However, lung consolidations, visible on ultrasound, are not pathognomonic of pneumonia.12 Consolidations can be seen in pulmonary oedema, pulmonary embolism, atelectasis, pulmonary contusions, tumours, interstitial diseases – such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic sclerosis – … as well as other pathologies.

SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia has ultrasound findings very similar to other viral infections of the lower respiratory tract, extensive and bilateral involvement, in the form of B-lines and subpleural consolidations. Again, ultrasonography is superior to clinical assessment, physical examination and chest radiography for the diagnosis of lung involvement.5,13

Our study aimed to establish the role of lung ultrasound in determining the aetiology of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and to determine a cut-off point with acceptable sensitivity and specificity, helping to prioritise which patients may benefit most from antibiotic treatment.

This study's results should be interpreted with an understanding of its limitations. Firstly, the sample size was small, and included only patients with an indication for hospital admission. Secondly, the aetiology was not found in 5 of 10 patients in the CAP group, although the aim was to reasonably rule out the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, recruitment was not consecutive, but based on the availability of the principal investigator (during his working hours). Finally, the physician who performed the lung ultrasound scans was aware of the SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis of pneumonia, given the need to determine isolation and infection transmission control measures. On the other hand, we must also consider that, during the months of the study, the high incidence may have led to the pulmonary involvement being attributed to SARS-CoV-2 rather than to other microorganisms.

Future studies should explore the role of the lung score for guidance and therapeutic monitoring in a larger sample size.

The combination of lung ultrasound findings, with a lung score greater than 10, complementing the other complementary tests, may be an excellent tool for predicting the aetiology of pneumonia.

Authorship/collaboratorsAll the authors contributed to this study.

Conception and design: YTC, AGH. Analysis and interpretation: YTC. Data collection: YTC, AGH, LDD, PGM, AGR, SGP, AVA, JHJ. Article redaction: YTC, AMV, LDD, PGM, EGA. Critical review of the article: YTC, EMH. Final approval of the article: YTC, AGH, AMV, LDD, PGM, EMH, AGR, SGP, AVA, JHJ, EGA. Statistical analysis: YTC. General responsibility: YTC.

The principal researcher, Yale Tung Chen, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Y. Tung-Chen, A. Giraldo Hernández, A. Mora Vargas et al. Impacto de la ecografía pulmonar durante la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2: distinción entre la neumonía viral y la bacteriana. Reumatol Clín. 2022;18:546–550.