Glucocorticoids (GC) constitute one of the cornerstones of therapy for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and are likely the most frequently prescribed chronic therapy after methotrexate. Both in surveys (QUEST-RA) and in trials about half of RA patients are on chronic GC therapy, with considerable variation between countries.1 It was expected that the introduction of targeted therapies such as the biologics would lead to reductions in GC use, but this has not really materialized.2

GC are associated with many adverse events, and treatment guidelines always stress that GC use must be as brief as possible, and at the lowest possible dose. So there is a discrepancy between ‘the real world’ and the guidelines (and pharma marketing).

The purpose of this viewpoint is to provide a realistic perspective on the current state of the art regarding the balance of benefit and harm of GC in RA, and to compare disease-modifying strategies that include GC with strategies that include biologics and synthetic targeted agents. It is not a systematic review, although the reader is pointed to other reviews for reference.

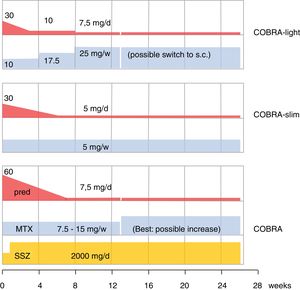

Notes on scope and definitionsLow dose GC therapy is defined as 7.5mg/d of prednisolone equivalent or less, and intermediate dose as >7.5 and ≤30mg/d.3 Most studies on GC have employed doses between 5 and 10mg/d. Some have started with a high dose (30–60mg/d) rapidly ‘stepping down’ to low dose, and some have looked at ‘bridging strategies’ where intermediate doses were given for the initial months, either as oral therapy or as repeated intramuscular injections. Intravenous pulse therapy has rarely been studied and falls outside the scope of this viewpoint.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are those drugs that are able to alter the course of disease, and this is usually translated to mean that the drug is able to slow or halt the progression of joint damage as assessed on radiographs of hands and forefeet. Traditional DMARDs such as methotrexate (MTX), sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine were also called ‘slow-acting’ and distinguished from GC because the latter act rapidly. Until quite recently, GC were not regarded as DMARD because of a wrongly held belief that GC did not slow progression of damage. Despite quite convincing evidence to the contrary (dating back to the early 1960-ies!),4 this belief is tenacious, and many review articles on the treatment of RA still distinguish between ‘traditional DMARDs’ and GC. Newer DMARDs are often called ‘Targeted therapies’ and include targeted biologicals (‘bDMARDs’) and targeted synthetic agents (‘tsDMARDs’; currently only Janus kinase-inhibitors).

‘Treat to target’ (T2T) is an ill-defined concept: both the specified target and the treatment protocol varies widely; most research in treat-to-target is in early RA.

Regarding outcome measurement, In RA trials ACR (American College of Rheumatology) response (suite: 20-50-70)5 and DAS28 (Disease Activity Score-28 joints),6 including EULAR response7 are most commonly used. Although both perform admirably in distinguishing active from placebo, and also weak from strong drug treatment, they work best in the setting of moderate to severe disease activity. Both are suboptimal in the setting of low disease activity or remission.

Evidence for benefit of treat-to-target and combination therapy in early diseaseA systematic review on T2T published in 2017 included 16 studies.8 Only 6 of these compared T2T with usual care (usually MTX monotherapy), providing some evidence that T2T is better, via earlier achievement of desired state. The 10 other trials compared different strategies against each other.

There is a substantial body of evidence for the benefit of GC in early RA, but much less for established RA; this is discussed below. This contrasts with the evidence for most other therapies, where the focus is on established RA. Also, most GC trials describe a treatment strategy where GC combined with other DMARDs is compared to DMARDs alone. For non-GC traditional DMARDs there is usually evidence for both combination therapy and monotherapy. For the biologics and tsDMARDs, the most frequently studied combination is that with MTX.

In registration (phase 3) trials of new DMARDs, most frequently patients with an insufficient response to MTX are randomized to additional placebo or the new DMARD. This is technically also a combination study, but it supplies little information on the true value of the combination because patients have already shown insufficient response (or failure) on MTX.9

For non-GC DMARD strategies mostly initial combo vs MTX monotherapy studies have been performed. Recent and older reviews collected very limited evidence that initial combo is better: most trials were negative, except for some evidence to suggest a benefit of ‘triple therapy’ (MTX+SSZ+HCQ) over MTX monotherapy.10,11

In the course of their development, all targeted agents have been studied in early RA (MTX naïve patients), where MTX monotherapy was compared with the combination, sometimes also with a third arm (targeted agent monotherapy).

A recent review12 summarized the results as follows: for disease activity a combination works better than MTX monotherapy; the new agent as monotherapy is only marginally better than MTX monotherapy, with the possible exception of tofacitinib monotherapy. More specifically, MTX + several biologics (abatacept, adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, rituximab, tocilizumab); and tofacitinib monotherapy resulted in an ACR50 response range of 56–67%, compared to 41% for MTX monotherapy. For damage, several MTX-biologic combinations (adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab, or infliximab) were statistically superior to MTX monotherapy, but in all treatment groups the estimated mean 1-y change was less than the minimal clinically important difference (5 units on the Sharp van der Heijde score13). Since this review, similar evidence for baricitinib has been published.14

Evidence for GC-DMARD strategiesAs stated above, most evidence for the efficacy of GC is in early RA. However, this is about to change as the GLORIA trial has recently closed inclusion and will present results in 2021. It is a large (n=452) pragmatic trial running in 7 European countries that compares the addition of 5mg/d prednisolone or placebo to standard of care therapy in RA patients aged 65+.15 Also, a withdrawal study presented at last year's American College of Rheumatology meeting showed that patients in low disease activity on tocilizumab plus low-dose GC were worse off if they tapered the GC, indicating continued efficacy beyond that of tocilizumab.16

The older literature is already conclusive on the efficacy of GC; effective in this review is shorthand for improvement on signs and symptoms AND slowing of damage progression; effects are consistent, as summarized in Cochrane reviews.4,17,18 As designer of COBRA, the first step-down trial, this schedule has a special place in my heart.19 Since its publication, its evidence has been replicated (BeSt trial20,21) and the schedule has been shown to be effective in lower dose modifications,22,23 as shown in Fig. 1. However, more simple schedules are also effective24–26. The benefits of early GC also extend to less starts of expensive biologic therapy,20,26 and counteraction of the systemic inflammatory effects that may include glucose intolerance, lipid disorders, mood disturbance and weight loss.19,27,28 Finally, GC co-therapy reduces the chance of hypersensitivity reactions to other antirheumatic drugs.19 In Amsterdam an interesting experiment studied glucose metabolism during a week of 60 or 30mg/d prednisolone in early untreated RA.29 These patients subsequently went on in the COBRA-light trial.22 41 patients were given 60 or 30mg/d. At baseline 23 patients had impaired glucose tolerance, and 3 had unrecognized diabetes type 2! The extent of glucose intolerance correlated with disease activity. After 1 week of either 30 or 60mg/d prednisolone, the mean glucose tolerance was unchanged. However, 7 patients with initially impaired tolerance progressed to diabetes mellitus, whereas 9 regressed to normal! Even in these early patients, progression to diabetes was more likely with longer symptom duration (36 v 16 weeks).

So how does combination therapy that includes GC compare with biologic therapy? Quite well, actually. The most well-known example is the BeSt trial where infliximab plus high dose methotrexate was indistinguishable from traditional COBRA therapy (treatment schedule, see Fig. 1) in efficacy.20 A recent review confirmed this with other GC schedules and biologics (Fig. 2).10 These results strongly suggest biologics should not be started in early RA before a combination that includes GC has been tried.

Systematic review of combination of TNF inhibitors and methotrexate (aTNF+MTX) compared to traditional combination therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Forest plots show mean (95%CI) difference per trial, and weighted mean difference (random effects model) over all trials. Only traditional combinations (DMARD comb) that contain glucocorticoids (GC, light blue) are as good as aTNF+MTX, other combinations (dark blue) are not. Middle blue rhomboid: overall estimate. DAS28: Disease activity Score-28 joints; SvdH (erosion): Sharp van der Heijde radiographic damage erosion subscore; Double: MTX+sulfasalazine; Triple: Double+hydroxychloroquine. GC: glucocorticoids; iv: intravenous. Trial references: APPEAL,39 BeSt (T is trial arm 3, with COBRA; D is trial arm 2, with Double)21; IMPROVED40; LARA41; RACAT42; TEAR43; IDEA44; SWEFOT.45

Most concern with GC in RA is not whether they work, but the ‘certainty’ that the harm outweighs any benefit. The number of observational studies that ‘prove’ this point increases every day, but in this (and many other) setting observational studies can never overcome the strong confounding by indication.30–32 This occurs because patients with poor prognosis are not only more likely to receive these agents, and poor prognosis RA is itself associated with many of the adverse events that are traditionally associated with GC. A recent example of this, only presented in abstract is a study from the CATCH cohort, that looked at 1689 early RA patients33: 59% received GC within the first 3 months (30% oral). These patients were older, less likely to be employed, had shorter disease duration, were more often rheumatoid factor or anti-citrullinated protein antibody positive, and were worse in all indicators of disease activity, and in physical disability scores. They had a worse course in the first year including more biologic starts.

In contrast, the experience from randomized trials (where by definition GC therapy is not associated with RA prognosis) consistently contradicts that low-dose GC (≤7.5mg prednisolone equivalent/d) given for extended periods is associated with excessive harm. However such evidence has proved hard to publish: a systematic review is still languishing in abstract form.34 However, a published case in point is our series on the long-term effects seen in the COBRA cohort: evidence for prolonged protection against damage,35 and no signs of excessive harm36 or increased mortality.37 It is certain that GC can cause serious harm, but it is highly likely that such harm is mostly seen in conditions where GC are given for long periods in high doses. Such conditions include complicated lupus and vasculitis, but most are non-rheumatologic, such as lymphoma.

In conclusion, it is time we dropped our strange reservations against the inclusion of GC in our treatment armamentarium, as a ‘normal’ drug, with pro's and con's like any other treatment. This includes getting rid of our collective self-denial, where guidelines (‘short-term’, ‘taper as rapidly as possible’38) are completely at odds with daily practice (about 50% of our RA patients on long-term GC therapy), but also optimal attention to effective preventive measures (screening and treating comorbidity, bone protection). Finally, more public funding and research effort must be spent on acquiring more knowledge about this essential agent.