Sleep problems are common in spondyloarthritis (SpA), but the factors associated with them are only partially known. In this study, responses to item #16 from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society-Health Index (ASAS HI) that explores the sleep category according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) were compared between psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and axial SpA (axSpA).

MethodsPost hoc analysis of a multicentre cross-sectional study included a total of 201 consecutive patients. The prevalence, correlations, and disease factors associated with a positive response to item #16 were analyzed in both SpA populations.

ResultsForty-eight/111 (43.2%) patients with axSpA and 42/90 (46.7%) with PsA reported sleep problems. There was a moderate–high correlation between item #16 and the ASAS HI sum score in both populations (r≥.59). In axSpA, poor sleep was associated with disease activity (OR 8.45, p<.001), biological therapy use (OR .24, p<.05) and CRP levels (OR .16, p<.05). In PsA, disturbed sleep was independently associated with disease activity showing a dose-response effect (OR 1.16, p<.001). Taking both populations together, disease severity (OR 6.33, p<.001) and axSpA (OR .50, p<.05) were independently associated with a positive response to item #16. Correlations between the different components of the ASAS HI and item #16 were markedly different in both populations.

ConclusionsA positive response to item #16 was common in both SpA phenotypes. However, the link between inflammatory burden and disturbed sleep was higher in axSpA than in PsA.

Los problemas del sueño son comunes en la espondiloartritis (SpA), pero los factores asociados a ellos solo se conocen parcialmente. En este estudio, se compararon las respuestas al ítem 16 de ASAS HI (Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society-Health Index) que explora la categoría del sueño, de acuerdo a ICF (International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health) entre artritis psoriásica (PsA) y Spa axial (axSpA).

MétodosEl análisis post hoc de un estudio transversal multicéntrico incluyó un total de 201 pacientes consecutivos. Se analizaron en ambas poblaciones de SpA la prevalencia, las correlaciones y los factores de la enfermedad asociados a la respuesta positiva al ítem 16.

ResultadosUn total de 48/111 (43,2%) pacientes con axSpA y 42/90 (46,7%) con PsA reportaron problemas del sueño. Existió una correlación de modera a alta entre el ítem 16 y la puntuación acumulada de ASAS HI en ambas poblaciones (r≥0,59). En axSpA, el sueño escaso se asoció a la actividad de la enfermedad (OR 8,45, p<0,001), el uso de terapia biológica (OR 0,24, p<0,05) y los niveles de PCR (OR 0,16, p<0,05). En la PsA, la perturbación del sueño estuvo independientemente asociada a la actividad de la enfermedad, lo cual refleja un efecto dosis-respuesta (OR 1,16, p<0,001). Considerando ambas poblaciones conjuntamente, la severidad de la enfermedad (OR 6,33, p<0,001) y axSpA (OR 0,50, p<0,05) estuvieron asociadas de manera independiente a la respuesta positiva al ítem 16. Las correlaciones entre los diferentes componentes de ASAS HI y del ítem 16 fueron marcadamente diferentes en ambas poblaciones.

ConclusionesLa respuesta positiva al ítem 16 fue común en ambos fenotipos de SpA. Sin embargo, el vínculo entre carga inflamatoria y perturbación del sueño fue mayor en axSpA en comparación con PsA.

The spondyloarthritis(SpA) concept encompasses a range of conditions including axial spondyloarthritis(axSpA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) among others.1 It is estimated that axSpA can affect 1.6% of the general population, while these estimates approximate 0.6% of the adult population in PsA.2,3 The global impact that these diseases have on individuals, societies, and health systems is enormous, especially considering that most of these conditions are diagnosed between the third and fourth decade of life. The consequent loss in labor productivity that this entails is associated with worse quality of life (QoL), higher disease activity, worse physical function, and mental distress.4 Impaired ability to work also has obvious financial implications.4

Treatment goals in SpA may be different for physicians and patients. Thus, doctors tend to seek a remission of disease inflammatory activity, while the meaning of remission from the patient's perspective needs to be explored further as it may differ considerably with respect to the physician's view.4 For example, patients with rheumatoid arthritis characterized remission as decreased daily impact of their condition and the feeling of return to normality.5 Therefore, it is not uncommon to find disparate results between the measures of disease activity collected by physicians and the patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs).4,6,7

Poor sleep has been reported in 35–90% of patients with axSpA.8 Disturbed sleep is an important aspect of the disease for these patients and reflects the severity of disease activity, pain, fatigue, and functional disability. However, the direction of these relationships is undetermined.8 A recent PsA study reported a prevalence of sleep disturbances of 38%.9 In adjusted analysis, pain, fatigue, and worse physical function were associated with sleep disturbances. Sleep disturbances, pain, and anxiety/depression were associated with fatigue, whereas only fatigue was associated with anxiety/depression.9 As with axSpA, this study results reflect that the direction between altered sleep and other PsA-related features is also unclear.

The PsA impact of disease (PsAID) questionnaire and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society-Health Index (ASAS HI) are two instruments designed to capture the impact that these conditions generate in patient's dailylife.10,11 Both contain specific items to assess disturbed sleep. Due to its validity and feasibility, both are being increasingly used in clinical routine.12 In the present work, we compared responses to ASAS HI item #16 (“I sleep badly at night”) between patients with PsA and axSpA. This information can help shed light on the intricate relationships between both diseases and this QoL aspect.

Patients and methodsThis is a post hoc comparative analysis of two observational cross-sectional studies in which we verified the construct and discriminant validity of ASAS HI in axSpA and PsA. The inclusion/exclusion criteria, methodological details, main results, and ethical considerations, applicable to both studies, have been published elsewhere.13,14 This study complies with the declaration of Helsinki. The ethics committee of Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (Oviedo-Spain) and Hospital Sierrallana (Torrelavega-Spain) approved the research protocol of each study. Informed consent has been obtained from the subjects of both studies.

Briefly, detailed data on the family history of the disease, educational level, comorbidities, received treatments, analytical data, structural damage, disease sub-phenotypes, and several composite outcome measures were collected. The latter were used as external anchors to validate the psychometric properties of the ASAS HI in both subpopulations.13,14

As disease impact outcome we used the ASAS HI. The ASAS HI is a linear composite measure based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (also known as ICF) containing 17 items which address aspects of pain, emotional functions, sleep, sexual functions, mobility, self-care, and community life. Each positive answer is scored 1 while a negative answer is scored 0. The final score is the sum of individual items, so that the higher the score, the greater the negative impact due to the disease.11 Although the PsAID remains the gold standard for estimating PsA health-related QoL, we have previously shown a high correlation between ASAS HI and PsAID [r: 0.75 (95%CI: 0.64–0–83)].14 In addition, item #16 of ASAS HI (dependent variable in this study) is one of the strongest estimators associated with a PsAID high-impact disease (OR 7.1, p<0.05),15 thereby rendering ASAS HI as an adequate tool to assess QoL in both populations.

Statistical analysisA descriptive statistical analysis of all variables was performed, including central tendency and dispersion measures for continuous variables, and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. To test the differences between quantitative variables, parametric (Student's T test) and non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis H) were used according to the goodness of fit test. Differences between qualitative variables were measured by a Pearson's chi-square and Fisher's exact tests. The distribution of the components of ASAS HI was compared between both diseases. Pearson's r was used to analyze the correlations between item #16 with the sum score of the ASAS HI, as well as between this item and each individual component of this questionnaire. These correlations were represented through Pearson's correlation matrices. Disease severity was defined as BASDAI>4+ASDAS-CRP>2.1+DAPSA>14+physician's global disease assessment>4.A backward stepwise approach multivariate model was developed to evaluate the explanatory disease variables associated with a positive statement to item # 16. The variables included in the model were: age, sex, disease duration, depression, smoking, biologic therapy, C-reactive protein (CRP), BASDAI, ASDAS, and DAPSA. Statistical significance was set at a value below 5%. Data were analyzed using the R statistical software package.

ResultsSummary of study populationThis analysis included 111 consecutive patients with axSpA and 90 consecutive patients with PsA. Compared to axSpA, patients with PsA were older (55.3±14.3 years versus 43.3±10.6 years, p<0.001), were receiving fewer biological therapies at the inclusion visit (44.4% versus 55.9%, p<0.05); however, more PsA subjects were in remission/low activity upon study entry (73% versus 48.6%, p<0.001). Table 1 summarizes the main features of both populations.

Disease features of both populations.

| Axial spondyloarthritis | N: 111 | Psoriatic arthritis | N: 90 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs (mean±SD) | 43.3±10.6 | Age (yrs), (mean±SD) | 55.3±14.3 |

| Disease duration, yrs (mean±SD) | 7.6±6.8 | Arthritis duration (yrs), median (IQR) | 7 (3–14) |

| Psoriasis duration (yrs), median (IQR) | 16 (10–29) | ||

| Men, n (%) | 74 (66.7) | Men, n (%) | 52 (57.7) |

| AS, n (%) | 74 (66.7) | Plaque psoriasis, n (%) | 75 (83.3) |

| Peripheral involvement, n (%) | 18 (16.2) | Nail disease, n (%)≥3 | 33 (36.7) |

| Affected body areas, n (%) | 61 (67.8) | ||

| Family history, n (%) | 16 (14.4) | Family history of psoriasis, n (%) | 37(41.1) |

| Family history of PsA, n (%) | 6 (6.7) | ||

| Primary education, n (%) | 43 (38.7) | Primary education, n (%) | 25 (27.8) |

| Secondary education, n (%) | 34 (30.6) | Secondary education, n (%) | 45 (50) |

| University degree, n (%) | 34 (30.6) | University degree, n (%) | 20 (22.2) |

| Tobacco, n (%) | 44 (39.6) | Diabetes, n (%) | 13 (14.4) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 18 (16.2) | Hypertension, n (%) | 37 (41.1) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 14 (12.6) | Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 30 (33.3) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 6 (5.4) | Obesity, n (%) | 21 (23.3) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 26 (23.4) | Smokers, n (%) | 14 (15.6) |

| Cardiovascular events, n (%) | 1 (0.9) | Cardiovascular events, n (%) | 6 (6.7) |

| Enthesitis, n (%) | 8 (7.2) | Axial pattern, n (%) | 14 (15.6) |

| Anterior uveitis, n (%) | 14 (12.6) | Oligoarthritis, n (%) | 42 (46.7) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease, n (%) | 6 (5.4) | Polyarthritis, n (%) | 34 (37.8) |

| HLA-B27, n (%) | 88 (79.3) | ||

| NSAID use, n (%) | 89 (80.2) | Conventional DMARDs, n (%) | 81 (90) |

| Biologic therapy, n (%) | 67 (60.4) | Biological therapy, n (%) | 37 (41.1) |

| BASDAI, mean (SD) | 3.4 (2.3) | DAPSA, mean (SD) | 9.7 (7.8) |

| ASDAS-CRP, mean (SD) | 2.1 (0.8) | PsAID, mean (SD) | 2.8 (2.3) |

| ASAS-HI, mean (SD) | 5.4 (3.8) | ASAS-HI, mean (SD) | 5.8 (4.3) |

yrs: years, SD: standard deviation, n: numbers, AS: ankylosing spondylitis, HLA: human leukocyte antigen. NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, BASDAI: bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity, ASDAS-CRP: ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score-C-reactive protein, ASAS-HI: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society-Health Index, IQR: interquartile range, PsA: psoriatic arthritis, DMARDs: Disease Modifying AntiRheumatic Drugs, DAPSA: Disease Activity index for PSoriatic Arthritis, PsAID: Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease.

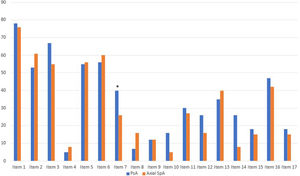

The distribution of the different ASAS HI components between both subgroups is represented in Fig. 1. The only ASAS HI item with a significantly higher positive response among axSpA women (89.2%) compared to axSpA men (70.3%) was item #1 (“pain sometimes disrupts my normal activities,” p=0.027). The only ASAS-HI item with a significantly higher positive statement among PsA women (73.3%) compared to PsA men (45.6%) was item #6 (‘I am less motivated to do anything that requires physical effort’, p=0.017).

Distribution of the different ASAS HI components among both study group. Item 1: Pain sometimes disrupts my normal activities; Item 2: I find it hard to stand for long; Item 3: I have problems running; Item 4: I have problems using toilet facilities; Item 5: I am often exhausted; Item 6: I am less motivated to do anything that requires physical effort; Item 7: I have lost interest in sex; Item 8: I have difficulty operating the pedals in my car; Item 9: I am finding it hard to make contact with people; Item 10: I am not able to walk outdoors on flat ground; Item 11: I find it hard to concentrate; Item 12: I am restricted in traveling because of my mobility; Item 13: I often get frustrated; Item 14: I find it difficult to wash my hair; Item 15: I have experienced financial changes because of my rheumatic disease; Item 16: I sleep badly at night; Item 17: I cannot overcome my difficulties. ASAS HI: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society-Health Index.

Forty-eight (43.2%) patients with axSpA reported a positive response to item #16. There was a moderate-high correlation between item #16 and the ASAS HI sum score (r: 0.60). The best correlations between this item and the rest ASAS HI components were found with item #1 referred to pain (r: 0.40) and #13 referred to feelings of frustration (r: 0.42). Fig. 2a illustrates the matrix of correlations of the different components of the ASAS HI in this study group. Upon multivariate analysis, poor sleep was related to disease activity measured by ASDAS (OR 8.45, 95% CI: 3.26–27.80, p<0.001), biological therapy use (OR 0.24, 95% CI: 0.06–0.87, p<0.05), and CRP levels (OR 0.16, 95% CI: 0.02–0.69, p<0.05). High BASDAI activity (OR 5.23, 95% CI: 2.19–13.21, p<0.001) or high ASDAS activity (OR 6.12, 95% CI: 2.52–15.69, p<0.001) were also related to poorer sleep. Table 2 shows the uni and multivariate models used for axSpA.

Matrix of correlations of ASAS HI and its components in axial spondyloarthritis (a) and psoriatic arthritis (b). Higher correlations appear darker while lower correlations make the color more subdued. Item 1: Pain sometimes disrupts my normal activities; Item 2: I find it hard to stand for long; Item 3: I have problems running; Item 4: I have problems using toilet facilities; Item 5: I am often exhausted; Item 6: I am less motivated to do anything that requires physical effort; Item 7: I have lost interest in sex; Item 8: I have difficulty operating the pedals in my car; Item 9: I am finding it hard to make contact with people; Item 10: I am not able to walk outdoors on flat ground; Item 11: I find it hard to concentrate; Item 12: I am restricted in traveling because of my mobility; Item 13: I often get frustrated; Item 14: I find it difficult to wash my hair; Item 15: I have experienced financial changes because of my rheumatic disease; Item 16: I sleep badly at night; Item 17: I cannot overcome my difficulties. ASAS HI: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society-Health Index.

Uni and multivariate models associated with positive responses to item #16 in axSpA.

| Variable | Univariate modelOR (95%CI) | p-Value | Multivariate modelOR (95%CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) | 0.75 | 0.97 (0.88–1.07) | 0.54 |

| Sex (male) | 0.75 (0.21–2.70) | 0.66 | ||

| Disease duration | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 0.74 | ||

| Biologic use | 0.26 (0.06–0.98) | 0.06 | 0.24 (0.06–0.87) | 0.04 |

| Depression | 2.14 (0.18–29.9) | 0.54 | ||

| BASDAI | 0.87 (0.39–1.97) | 0.73 | ||

| ASDAS | 13.45 (1.03–233.9) | 0.06 | 8.45 (3.26–27.8) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 3.69 (0.89–18.70) | 0.09 | 2.91 (0.79–12.2) | 0.12 |

| CRP | 0.14 (0.01–1.04) | 0.08 | 0.16 (0.02–0.69) | 0.03 |

axSpA: axial spondyloarthritis; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; BASDAI: bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index; ASDAS: ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score; CRP: C-reactive protein.

Forty-two (46.7%) PsA patients reported poor sleep. Moderate-high correlation (r: 0.59) was found between the ASAS HI sum score and item #16. The highest correlations between item #16 and the remaining ASAS HI items were with #6 (r: 0.42) and #13 (r: 0.49). However, correlation with pain was almost absent (r: 0.13). Fig. 2b illustrates the matrix of correlations of the different components of the ASAS HI in the PsA group. The only factor independently associated with item #16 was disease activity measured by DAPSA (OR 1.16, 95% CI: 1.08–1.26, p<0.001) with a dose-response effect. Thus, patients with moderate-high DAPSA activity showed a stronger relationship with item #16 (OR 5.02, 95% CI: 1.63–17.69, p=0.002). Table 3 shows the uni and multivariate models used for PsA.

Uni and multivariate models associated with positive responses to item #16 in PsA.

| Variable | Univariate modelOR (95%CI) | p-Value | Multivariate model OR(95%CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.4 | ||

| Sex (Male) | 0.51 (0.16–1.57) | 0.3 | ||

| Disease duration | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | 0.8 | ||

| Biologic use | 0.47 (0.14–1.40) | 0.2 | ||

| Obesity | 0.84 (0.24–2.75) | 0.8 | ||

| DAPSA | 1.22 (1.11–1.36) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.08–1.26) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 1.74 (0.43–7.36) | 0.4 |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; DAPSA: disease activity index for psoriatic arthritis.

Taking both populations together, a severe disease (OR 6.33, 95% CI: 3.31–12.63, p<0.001) and axSpA (OR 0.50, 95% CI: 0.25–0.95, p<0.05) were independently associated with a positive statement to item #16.

DiscussionIn this post hoc analysis, disturbed sleep correlated well with ASAS HI sum score, a suitable estimator of disease impact in PsA and axSpA. Although in both diseases item #16 was correlated with item #13, referred to the ICF category of emotional functions, the correlation between pain and sleep was closer in axSpA than in PsA. In the latter, there was a correlation between sleep and the motivation ICF category (closely associated with fatigue in this instrument). Therefore, drivers of disturbed sleep appear to be somewhat different in both SpA populations. On the other hand, we found a clear relationship between the activity and severity of both diseases and the presence of sleep disturbances. When both populations were analyzed together, patients with axSpA were more likely to report a positive response to item #16 (OR 0.50). Also, in patients with axSpA a tighter connection between inflammatory activity and sleep was detected, in such a way that those patients under biological therapy reduced the possibility of reporting disturbed sleep by 76%, while those with normal CRP did so by 84%.

Although the present study is based only on the components of ASAS HI, we have previously shown that ASAS HI and PsAID are highly correlated.14 Furthermore, the item #16 is one of the components most strongly linked to a PsAID high impact disease.15 Therefore, ASAS HI seems an adequate impact estimator of the different facets of QoL in both conditions.

As in other studies,8,9,16,17 we have shown that disease activity is clearly associated with sleep disturbances. Moreover, this relationship is dose-dependent in both types of patients. However, there are some differences between disturbed sleep drivers among both SpA phenotypes that deserve to be mentioned. Thus, for example, although pain is the aspect mostly reported by both types of patients among the ASAS HI items, the correlation between pain and poor sleep was pretty evident in axSpA but not so in PsA. In both diseases, the ICF category of emotional functions, represented by item #13, was associated with disturbed sleep. However, the ICF category of motivation to perform physical efforts (which is strongly linked to fatigue) was mostly associated with sleep disturbances in PsA, suggesting that fatigue is more clearly linked to poor sleep in PsA than in axSpA. In sum, in our study cohorts, poor sleep was explained by common factors to both diseases (disease activity, emotional functions), but also by more individual-related factors (fatigue-motivation in PsA and pain in axSpA).

Biological therapy is associated with better QoL outcomes, both physical and mental.18 Our patients with axSpA under biological therapy significantly reduced the possibility of reporting sleep disturbances, although we were unable to detect a similar effect in PsA. For their part, patients with axSpA and normal CRP values were significantly associated with lower chances of poor sleep. Overall, these data indicate that sleep disturbances are an integral part of the inflammatory process in axSpA, while in PsA these disturbances have a more multifactorial drift.16 Similarly, a clear fatigue-inflammation connection has been reported in axSpA, but not so in PsA.19,20

Some weaknesses of this study should be highlighted. Both study populations were relatively small and therefore not all the phenotypes of both processes were considered. Furthermore, the ASAS HI was designed for its interpretation as a whole and somewhat less through the sub-analysis of its different components. Also, we should keep in mind that emotional functions are linked to a very wide range of psychosocial concepts (anxiety, fear, uncertainty, sadness, depression, lack of motivation, anger, etc.) beyond frustration, so we still need to further explore the directions between poor sleep and these mental health components. The concept of severity used in this study (adding the activity metrics to the opinion of the evaluating physician) is not standard, and this can be criticized. Also, our findings between the use of biological therapies and sleep may be biased because the exposure to these therapies was not similar in both groups. Finally, item #16 analysis may result in a very indirect approach for the study of sleep disorders in these populations.

The strength of this study lies in being able to study a key aspect in the QoL of these patients (sleep) through an easily implementable tool in clinical routine such as the ASAS HI.12

Patients with axSpA and PsA frequently report sleep disturbances. The factors that drive sleep health may differ between the two conditions, so more research is needed. ASAS HI can help detect sleep disturbances, thus offering a more comprehensive and individualized approach to managing these diseases.

Compliance with ethical standardsThis study received the approval of the Ethical Committee for Clinical Research of the Principality of Asturias, Oviedo (Spain). The patients were informed of the study objectives and gave their consent to participate and publish the study.

FundingThis study has no funding.

Conflict of interestsAuthors declare no conflict of interests.