Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disease of uncertain etiology. Several drugs have been linked to the development of sarcoidosis or systemic granulomatous reactions indistinguishable from this disease. We present the clinical case of a patient diagnosed with breast cancer and undergoing treatment with capecitabine who, after developing systemic and musculoskeletal symptoms, was ultimately diagnosed with capecitabine-induced sarcoidosis.

La sarcoidosis es una enfermedad granulomatosa multisistémica de etiología incierta. Varios fármacos se han relacionado con el desarrollo de sarcoidosis o reacciones sistémicas granulomatosas indistinguibles de dicha enfermedad. Presentamos el caso clínico de una paciente diagnosticada de cáncer de mama y en tratamiento con capecitabina que tras comenzar con clínica sistémica y musculoesquelética es diagnosticada, finalmente, de sarcoidosis inducida por capecitabina.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of uncertain aetiology that mainly affects young adults.1 Current studies have shown that sarcoidosis is caused by a combination of genetic susceptibility, adaptive immune abnormalities, and environmental factors.2 Multiple factors associated with the development of the disease have been described, such as various infectious agents, exposure to different environmental products, and a number of different drugs.3

Clinical observationThe patient was a 44-year-old woman diagnosed with stage IV breast ductal carcinoma in 2016, initially treated with chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy. In January 2021, recurrence in bone was detected and treated with hormone therapy and denosumab, with a good radiological response to treatment. In February 2023, a control PET/CT scan was run in which liver metastasis was visualised, with a good response initially to treatment with chemotherapy and hormonal therapy. In November 2023, new tumour progression was detected at the hepatic level, for which reason treatment with capecitabine was initiated.

In December 2023, after the third cycle of capecitabine, the patient began with a low-grade fever of up to 37.7 °C and polyarthralgias, for which it was decided to admit her to complete the aetiological study. On examination, the patient presented pitting oedema in the lower extremities with inflammatory signs in both ankles and pain on mobilisation. In addition, she presented pain on palpation in knees and carpi but with no signs of arthritis in these joints. Cardiopulmonary auscultation was normal but abdominal examination was unusual. Blood tests showed an increase in C-reactive protein (15.53 mg/dl), leucocytosis with neutrophilia and an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) value of 77 U/l. The remainder of the additional tests run were either normal or negative (Table 1).

Results of analyses run.

| Lab Data | Result | Reference value |

|---|---|---|

| CRP | 15.53 mg/dl | ≤0.5 |

| ESR | 59 mm/h | 0−20 |

| ACI | 77.2 U/l | 13−63.9 |

| Leukocytes | 12,500 mm3 | 3900−10,200 |

| Neutrophils 10,600 mm3 | 1800−7400 | |

| Haemoglobin | 12.6 g/dl | 12−16,5 |

| Hematocrit | 37% | 36−46 |

| Platelets | 234,000 mm3 | 140,000−370,000 |

| RF | <10 IU/ml | ≤14 |

| Anti-CCP antibodies | <4.6 U/ml | 0−20 |

| ANA | Negative | |

| Urine sediment | Normal | |

| Uroculture | Negative | |

| Blood cultures | Negative | |

| CRP influenza A and B | Negative | |

| CRP SARS-CoV-2 | Negative | |

| Serologies | ||

| Syphilis | Negative | |

| Cytomegalovirus | Immunised. no data on acute infection | |

| Lyme | Negative | |

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ANA: antinuclear antibodies; Anti-CCP: anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; RF: rheumatoid factor.

Given the suspicion of symmetrical polyarthritis as a probable side effect of capecitabine, treatment with this drug was suspended and a tapering regimen of glucocorticoids was begun with a favourable clinical course, for which reason it was decided to restart treatment with capecitabine.

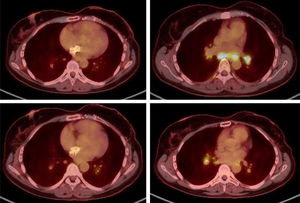

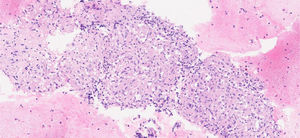

In February 2024, a PET/CT scan was requested to monitor the oncological disease, visualising multiple hiliomediastinal lymphadenopathies, with a characteristic pattern of granulomatous inflammatory disease (Fig. 1). A bronchoscopy was performed with a biopsy of these adenopathies, with an anatomopathological finding of non-necrotising granulomatous lymphadenitis (Fig. 2), confirming the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

The patient was asymptomatic and without any clinical repercussions at the pulmonary level, with normal respiratory function in tests, while also maintaining good oxygen saturation. For this reason, treatment with capecitabine was continued and active follow-up was carried out without any other additional treatment measures. A follow-up PET/CT scan run at 2 months showed an overall decrease in the intensity of uptake of hiliomediastinal adenopathies.

The only symptomatology presented by the patient in the following months was plantar toxicity. In September 2024, elevation of tumour markers was detected, and tumour progression was confirmed in the PET/CT scan run in October 2024, thus capecitabine was suspended. In this same test, total resolution of the hiliomediastinal lymphadenopathies described above was observed.

DiscussionSarcoidosis is a complex multisystem disease with variable phenotypes and great clinical heterogeneity. Pulmonary manifestations are the most frequent, however there may be involvement at other levels. Musculoskeletal manifestations appear in up to 15% of patients, with the most frequent joint pattern being oligoarticular involvement, predominantly in large joints and lower limbs, especially in ankles (90%) with accompanying periarthritis.4

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis was based on the combination of three main criteria: compatible clinical findings, histological evidence of non-necrotising granulomas, and the exclusion of any other cause of granulomatous disorders. The differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis included infectious conditions, neoplasms, autoimmune diseases, and occupational and environmental diseases.5

Drugs may be linked to the development of sarcoidosis, or systemic reactions similar to sarcoidosis. The main families of drugs associated with this type of reaction are check-point inhibitors, antiretroviral drugs, tumour necrosis factor-alpha antagonists, and interferons.6

Capecitabine is an oral 5-fluoracil prodrug used as a chemotherapy agent in the treatment of solid tumours, primarily in colon and breast cancer. Its most frequent adverse effects are gastrointestinal alterations, mucositis, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, asthenia, fatigue, anorexia, hepatotoxicity and neurotoxicity.7

In the literature, two cases of sarcoidosis have been reported that developed after treatment with capecitabine, one in a patient diagnosed with colon cancer8 and the other in a patient diagnosed with breast cancer.9

On the website: https://www.ehealthme.com/ where data on the safety of post-marketing drugs was collected from 59,451 people on treatment with capecitabine, 17 people (0.03%) developed sarcoidosis, however only one of them was in the context of metastatic breast cancer, as in the case of our patient.10

The mechanism by which capecitabine is related to the development of sarcoidosis is unclear, although the main hypotheses are based on the changes that this drug gives rise to in the immune system. Capecitabine can induce activation of the immune system and generate an increase in proinflammatory cytokines, favouring the development of sarcoidosis.8,9

In this clinical case, the patient did not present clinical symptoms at the pulmonary level but did at the systemic and musculoskeletal level. Other possible diagnoses causing the symptoms were excluded and the histological presence of non-necrotising granulomas was confirmed. Given the clinical symptoms, the results of the additional tests run and the temporal relationship with the initiation of the drug, the diagnosis of capecitabine-induced sarcoidosis was reached.

ConclusionsMultiple drugs may be associated with indistinguishable granulomatous systemic reactions to sarcoidosis. In the event of a clinical picture and histological lesions compatible with sarcoidosis in a patient who has recently started a new drug, the possibility of this differential diagnosis should be taken into account.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.