To study the clinical characteristics and outcomes in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients who underwent cardiac surgery.

MethodsRetrospective analysis of 30 SLE patients who underwent cardiac surgery at a single center. Demographics, comorbidities, clinical and serologic characteristics, cardiovascular risk scores and treatment were recorded. Type of surgery, postoperative complications, mortality and histology were analyzed.

ResultsDisease duration at surgery was 2 years. Valve replacement was the procedure most frequently performed (53%), followed by pericardial window (37%). At least one postoperative complication developed in 63% (mainly infections). An aortic cross-clamp time ≥76min was associated with at least one postoperative complication (OR 6.4, 95% CI 1.1–35.4, P=.03). Early death occurred in 5 patients (17%) and late in 3 (10%); main causes were sepsis and heart failure. Disease activity was associated with pericardial window (OR 12.6, 95% CI 1.9–79, P=.007); lymphopenia≤1.200 (OR 10.1, 95% CI 1.05–97, P=.04); age≤30 years (OR 7.7, 95% CI 1.2–46.3, P=.02); and New York Heart Association class III (OR 7.0, 95% CI 1.1–42, P=.03). Postoperative infection was associated with length of hospital stay≥2 weeks (OR 54.9, 95% CI 5.0–602.1, P=.001); intensive care unit stay≥10 days (OR 20, 95% CI 1.6–171.7, P=.01); duration of mechanical ventilation ≥5 days (OR 16.9, 95% CI 1.5–171.7, P=.01); and pulmonary artery systolic pressure ≥50mmHg (OR 7.8, 95% CI 1.4–41.2, P=.01).

ConclusionsCardiac surgery in SLE confers high morbidity and mortality. SLE-specific preoperative risk scores should be designed to identify prognostic factors.

Estudiar las características clínicas y desenlaces de los pacientes con lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) intervenidos de cirugía cardiaca.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio retrospectivo de 30 pacientes con LES y cirugía cardiaca en un solo centro. Se registraron comorbilidades, características demográficas, clínicas, serológicas, riesgo cardiovascular, tratamiento, tipo de cirugía, complicaciones postoperatorias, mortalidad e histología.

ResultadosLa duración de LES al momento de la cirugía fue de 2 años. El procedimiento más frecuente fue recambio valvular (53%), seguido de ventana pericárdica (37%). Al menos una complicación postoperatoria se presentó en el 63% (principalmente infecciones). Un pinzamiento aórtico≥76min se asoció con al menos una complicación (OR 6,4; IC 95% 1,1–35,4, p=0,03). La mortalidad temprana ocurrió en 5 pacientes (17%) y tardía en 3 (10%); siendo las causas principales sepsis e insuficiencia cardiaca. La actividad de la enfermedad se asoció a la realización de ventana pericárdica (OR 12,6; IC 95% 1,9–79; p=0,007), presencia de linfopenia≤1.200 (OR 10,1; IC 95% 1,05–97; p=0,04), edad≤30 años (OR 7,7; IC 95% 1,2–46,3; p=0,02) y NYHA clase III (OR 7,0; IC 95% 1,1–42, p=0,03). El desarrollo de infección postoperatoria se asoció con estancia hospitalaria≥2 semanas (OR 54,9; IC 95% 5,0–6021; p=0,001), estancia en UCI≥10 días (OR 20; IC 95% 1,6–171,7, p=0,01), duración de ventilación mecánica ≥ 5 días (OR 16,9, IC 95% 1,5–171,7, p = 0,01) y PSAP≥50mmHg (OR 7,8; IC 95% 1,4–41,2; p=0,01).

ConclusionesLa cirugía cardiaca en LES se asocia a alta morbimortalidad.

Cardiac involvement is common in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It affects all the components of the heart, including the pericardium, conduction system, myocardium, valves and coronary arteries, with prevalence of 8.3% to 50% of coronary artery disease and valve defects, respectively.1

In a multiethnic cohort of SLE patients, it was shown that the risk factors of cardiac injury are the Afro/Latin American ethnic group, the presence of primary cardiac disease and the damage index; whereas involvement of the central nervous system and antimalarial treatment are protectors.2 An association has been demonstrated between the use of glucocorticoids and anticardiolipin antibodies and valve disease.3,4

In all, 25% of the patients with SLE developed pericarditis at some time. Constrictive pericarditis and tamponade are infrequent in SLE. Pericardial biopsy is not indispensable for diagnosis.5

In these patients, there is a predominance of involvement of left heart, since the mitral valve is most frequently affected, followed by the aortic valve.4 Valve defect can be asymptomatic or fulminant, with heart failure and bacterial endocarditis. Echocardiography is the best imaging study for the evaluation of valve changes; aside from providing information on ventricular function and indirect estimation of pulmonary artery pressure.6 Echocardiographic findings include valve thickening and mitral regurgitation, with a low prevalence of pulmonary hypertension.7,8

The definitive diagnosis is obtained with the histopathologic analysis of the valve. Libman-Sacks endocarditis is the most common cardiac lesion in SLE and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), and it is characterized by clusters of sterile fibrin and platelets that can result in valve changes or serve as a niche for bacterial infections.1 Other histopathological findings in the valves are fibrosis, neovascularization, infiltration of mononuclear cells and immune complexes.6,7

Cardiac involvement in SLE is a primary cause of morbidity and mortality, with premature subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events.8 Cardiac surgery is not performed as a routine practice in these patients. The information on outcomes is restricted to case reports,1,6,7 with mixed results that limit the identification of prognostic factors, combined with the fact that there are no preoperative protocols or postoperative strategies designed for these patients.

The purpose of the present study is to analyze the characteristics and outcomes of SLE patients who underwent cardiac surgery.

Patients and MethodsA retrospective study that included all the patients diagnosed with SLE (classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology)9,10 who underwent cardiac surgery between January 2004 and December 2014 in the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition Salvador Zubirán, a tertiary center in Mexico City. The same cardiovascular surgeon performed all of the interventions. The patients were followed for 1 year after the operation or until death. We excluded patients for whom there was insufficient information, those with primary APS or another connective tissue disease, and those whose operation was carried out in another institution.

Prior to surgery, we calculated the risk score for all of the patients using the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation (EuroSCORE) and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons score.11,12 Surgery was approved only if the risk of death according to the EuroSCORE was < 20%.

The ethics committee of our center reviewed and approved the study.

Clinical VariablesWe recorded information on comorbidities, the demographic, clinical and serological characteristics leading to the diagnosis of SLE, as well as the presence of secondary APS.13

At the time of surgery, we documented the following variables related to SLE: disease duration; use of immunosuppressive agents, acetylsalicylic acid or oral anticoagulants; disease activity according to the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI-2K)14; accumulated damage based on the Systemic Lupus International Collaborative Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index (SLICC/ACR SDI)15; anti-double-strand (ds) DNA; and complement C3 and C4.

The cardiovascular variables at the time of surgery included: New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class for heart failure (class I-IV)16; EuroSCORE II11; standard laboratory tests; type of surgery; emergent surgery (performed before the following workday), urgent surgery (in patients who were not admitted electively, but required surgery during the current hospital stay for medical reasons and could not be discharged without the definitive procedure)11 or elective surgery; operative time, cardiopulmonary bypass time and aortic cross-clamp time; transfusion requirements and bleeding (mL); type of valve prosthesis; days in intensive care unit (ICU); duration of mechanical ventilation; and length of hospital stay.

The following early and late complications (<1 month and 2–12 months, respectively), aside from death and its causes in accordance with the death certificate. The histological findings in the valve were also recorded.

Statistical AnalysisThe continuous variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]) or median (minimum and maximum range); the categorical variables as number and percentage. The differences between groups were analyzed by Student's t test or the Mann–Whitney U test (continuous variables), and chi-square or Fisher's exact test (categorical variables). We calculated odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using univariate logistic regression analysis. A P<.05 was considered to indicate significance and the values reported are from 2-tailed tests. We utilized STATA version 12.0 software package.

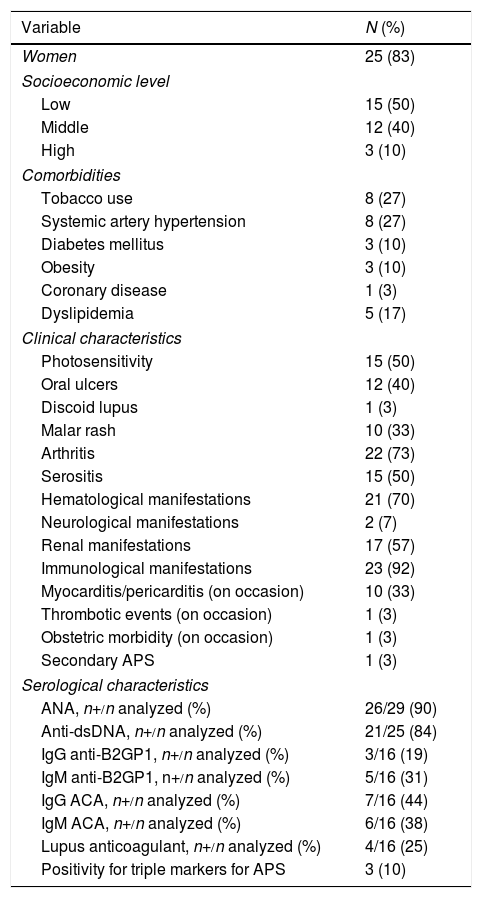

ResultsBaseline CharacteristicsThirty SLE patients underwent cardiac surgery during the study period. Twenty-five (83%) were women, with a median age of 27 years (range: 18–59). Half of the patients had a low socioeconomic level, and the main comorbidity was tobacco use and systemic hypertension, in 8 patients (27%). At diagnosis, 15 (50%) had serositis, whereas 10 (33%) developed myocarditis or pericarditis during the course of the disease. One patient (3%) had secondary APS; the most prevalent antiphospholipid antibody at the diagnosis of SLE was IgG anticardiolipin antibodies, present in 7 of 16 (44%). These characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Comorbidities and Demographic Characteristics and of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus at Diagnosis.

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Women | 25 (83) |

| Socioeconomic level | |

| Low | 15 (50) |

| Middle | 12 (40) |

| High | 3 (10) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Tobacco use | 8 (27) |

| Systemic artery hypertension | 8 (27) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (10) |

| Obesity | 3 (10) |

| Coronary disease | 1 (3) |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (17) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Photosensitivity | 15 (50) |

| Oral ulcers | 12 (40) |

| Discoid lupus | 1 (3) |

| Malar rash | 10 (33) |

| Arthritis | 22 (73) |

| Serositis | 15 (50) |

| Hematological manifestations | 21 (70) |

| Neurological manifestations | 2 (7) |

| Renal manifestations | 17 (57) |

| Immunological manifestations | 23 (92) |

| Myocarditis/pericarditis (on occasion) | 10 (33) |

| Thrombotic events (on occasion) | 1 (3) |

| Obstetric morbidity (on occasion) | 1 (3) |

| Secondary APS | 1 (3) |

| Serological characteristics | |

| ANA, n+/n analyzed (%) | 26/29 (90) |

| Anti-dsDNA, n+/n analyzed (%) | 21/25 (84) |

| IgG anti-B2GP1, n+/n analyzed (%) | 3/16 (19) |

| IgM anti-B2GP1, n+/n analyzed (%) | 5/16 (31) |

| IgG ACA, n+/n analyzed (%) | 7/16 (44) |

| IgM ACA, n+/n analyzed (%) | 6/16 (38) |

| Lupus anticoagulant, n+/n analyzed (%) | 4/16 (25) |

| Positivity for triple markers for APS | 3 (10) |

ANA, antinuclear antibodies; anti-ds (double-stranded) DNA; APS, antiphospholipid syndrome; IgG/IgM ACA, anticardiolipin antibodies; IgG/IgM anti-B2GP1, anti-beta 2 glycoprotein 1; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

The low prevalence of positive results for antiphospholipid antibodies at the diagnosis of SLE was due to the fact that only half of the patients had undergone testing for these antibodies at that time. However, over the course of the disease, 10 of 28 (36%) were found to be positive for IgG anticardiolipin, 15 of 28 (54%) for IgM anticardiolipin, 8 of 28 (29%) for IgG anti-beta 2 glycoprotein 1 (anti-B2GP1), 6 of 25 (24%) for IgM anti-beta 2 glycoprotein 1 (anti-B2GP1), and 7 of 24 (29%) for lupus anticoagulant.

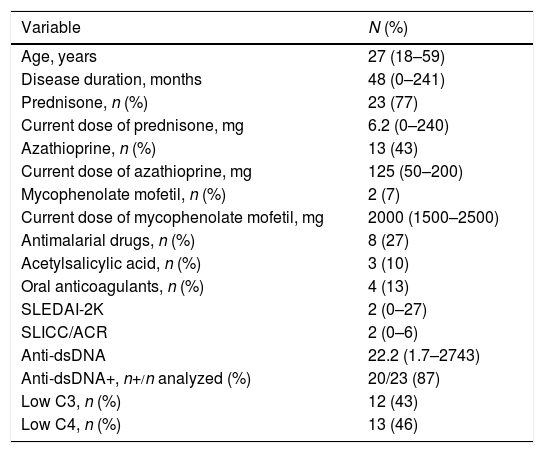

Characteristics at the Time of SurgeryThe duration of SLE was 48 months (range: 0–241). Twenty-three patients (77%) had been taking prednisone, with a median dose of 6.2mg (0–240); 13 (43%) received azathioprine, 2 (7%) took mycophenolate mofetil, and 8 (27%) antimalarial drugs. The disease activity according to the SLEDAI-2K was 2 (range: 0–27) and damage in terms of the SLICC/ACR was 2 (range: 0–6); 20 patients (87%) were positive for anti-dsDNA, and 4 (13%) were undergoing dialysis. We found no association between positive tests for anticardiolipin (IgG or IgM) at the diagnosis of SLE and valve defects (OR 1.5; 95% CI 0.2–7.6, P=.62). Table 2 shows these data.

Characteristics of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus at the Moment of Surgery.

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 27 (18–59) |

| Disease duration, months | 48 (0–241) |

| Prednisone, n (%) | 23 (77) |

| Current dose of prednisone, mg | 6.2 (0–240) |

| Azathioprine, n (%) | 13 (43) |

| Current dose of azathioprine, mg | 125 (50–200) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil, n (%) | 2 (7) |

| Current dose of mycophenolate mofetil, mg | 2000 (1500–2500) |

| Antimalarial drugs, n (%) | 8 (27) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid, n (%) | 3 (10) |

| Oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 4 (13) |

| SLEDAI-2K | 2 (0–27) |

| SLICC/ACR | 2 (0–6) |

| Anti-dsDNA | 22.2 (1.7–2743) |

| Anti-dsDNA+, n+/n analyzed (%) | 20/23 (87) |

| Low C3, n (%) | 12 (43) |

| Low C4, n (%) | 13 (46) |

Values expressed as medians (minimum-maximal) or n (%).

Anti-ds (double-stranded) DNA; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index; SLICC/ACR, Systemic Lupus International Collaborative Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index.

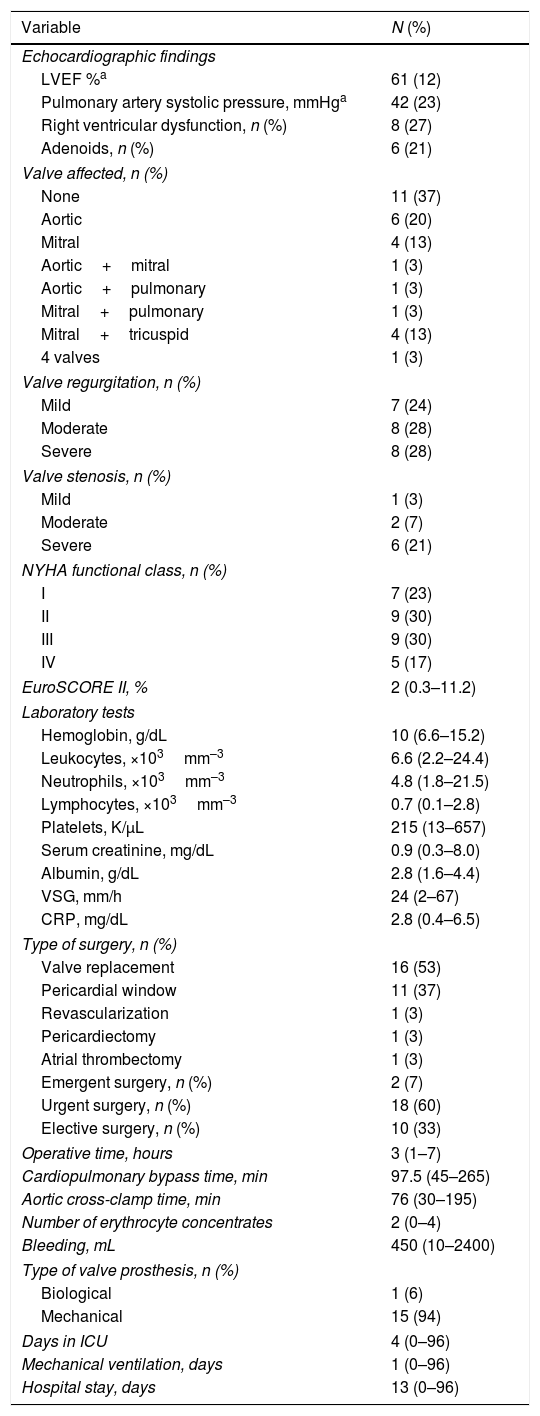

In all, 29 of 30 patients had undergone echocardiogram prior to surgery; 11 (37%) with no evidence of valve damage; in the remainder, the aortic valve was affected in 6 (20%); mitral in 4 (13%); mitral+tricuspid in 4 (13%); aortic+mitral, aortic+pulmonary, mitral+pulmonary and all 4 valves in 1 patient (3%), respectively. Valve regurgitation was more common than stenosis, and adenoids were observed in 6 cases (21%). The majority of the patients were in NYHA functional class II or III (9 patients, 30% of each group), and the median EuroSCORE II was 2% (range: 0.3–11.2).

Valve replacement was the most common procedure, performed in 16 patients (53%). The valves replaced were aortic (n=7), mitral (n=7), aortic+mitral (n=1) and mitral+tricuspid (n=1). Most of the prostheses were mechanical (15 patients, 94%); there was only 1 biological. The procedure for pericardial window was carried out in 11 patients (37%); in 9 of them, the indication was cardiac tamponade and, in 2, it was recurrent pericardial effusion. Nine of the 11 patients who had an intervention involving a pericardial window had undergone pericardiocentesis; in the remaining 2, the procedure was emergent. The 3 remaining patients underwent procedures for revascularization, pericardiectomy and atrial thrombectomy, respectively.

The surgical indication was urgent in 18 patients (60%), emergent in 2 (7%) and elective in 10 (33%). The hospital stay was 13 days (range: 0–96). Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the interventions.

Characteristics of Cardiac Surgery.

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Echocardiographic findings | |

| LVEF %a | 61 (12) |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure, mmHga | 42 (23) |

| Right ventricular dysfunction, n (%) | 8 (27) |

| Adenoids, n (%) | 6 (21) |

| Valve affected, n (%) | |

| None | 11 (37) |

| Aortic | 6 (20) |

| Mitral | 4 (13) |

| Aortic+mitral | 1 (3) |

| Aortic+pulmonary | 1 (3) |

| Mitral+pulmonary | 1 (3) |

| Mitral+tricuspid | 4 (13) |

| 4 valves | 1 (3) |

| Valve regurgitation, n (%) | |

| Mild | 7 (24) |

| Moderate | 8 (28) |

| Severe | 8 (28) |

| Valve stenosis, n (%) | |

| Mild | 1 (3) |

| Moderate | 2 (7) |

| Severe | 6 (21) |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | |

| I | 7 (23) |

| II | 9 (30) |

| III | 9 (30) |

| IV | 5 (17) |

| EuroSCORE II, % | 2 (0.3–11.2) |

| Laboratory tests | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 10 (6.6–15.2) |

| Leukocytes, ×103mm–3 | 6.6 (2.2–24.4) |

| Neutrophils, ×103mm–3 | 4.8 (1.8–21.5) |

| Lymphocytes, ×103mm–3 | 0.7 (0.1–2.8) |

| Platelets, K/μL | 215 (13–657) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.3–8.0) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.8 (1.6–4.4) |

| VSG, mm/h | 24 (2–67) |

| CRP, mg/dL | 2.8 (0.4–6.5) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |

| Valve replacement | 16 (53) |

| Pericardial window | 11 (37) |

| Revascularization | 1 (3) |

| Pericardiectomy | 1 (3) |

| Atrial thrombectomy | 1 (3) |

| Emergent surgery, n (%) | 2 (7) |

| Urgent surgery, n (%) | 18 (60) |

| Elective surgery, n (%) | 10 (33) |

| Operative time, hours | 3 (1–7) |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time, min | 97.5 (45–265) |

| Aortic cross-clamp time, min | 76 (30–195) |

| Number of erythrocyte concentrates | 2 (0–4) |

| Bleeding, mL | 450 (10–2400) |

| Type of valve prosthesis, n (%) | |

| Biological | 1 (6) |

| Mechanical | 15 (94) |

| Days in ICU | 4 (0–96) |

| Mechanical ventilation, days | 1 (0–96) |

| Hospital stay, days | 13 (0–96) |

Values expressed as medians (minimum-maximal) or n (%).

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; ICU, intensive care unit; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, classification of heart failure of the New York Heart Association.

Nineteen patients required cardiopulmonary bypass (16 valve replacements, 1 revascularization, 1 pericardiectomy and 1 atrial thrombectomy). The median duration of SLE was 6 years; the dose of prednisone at the time of surgery was 5mg (range: 0–50); 4 patients (21%) were receiving oral anticoagulation; the disease activity according to SLEDAI-2K was 1 (0–27); the SLICC/ACR was 2 (0–6) and 10 (77%) were positive for anti-dsDNA.

In all, 32% of the patients were in NYHA class II-III (6 patients per class), and the median EuroSCORE II was 2% (range: 0.3–9). The indication for surgery was urgent in 9 patients (47%). The median operative time was 4h (3–7), bleeding was 700mL (200–2400), and the hospital stay was 13 days (0–62). Twelve patients (63%) had a least 1 postoperative complication, infections being those most frequent (8 patients, 42%). Four patients died (21%), all during the first postoperative month.

Characteristics of the Patients Who Underwent Procedures for Pericardial WindowThese 11 patients had a shorter duration of SLE (median 5 months); they received doses of prednisone of 15mg (range: 0–240); they did not take oral anticoagulation therapy; disease activity according to SLEDAI-2K was 12 (0–26), accumulated damage by SLICC/ACR was 2 (0–5), and all were positive for anti-dsDNA.

Three patients (27%) were in NYHA functional class I, II and III, respectively, and only 2 patients (18%) showed valve involvement in the echocardiogram. The EuroSCORE II was 4% (range: 1–11); the median operative time was 1 hour (1–3); median bleeding was 30mL (10–1500), and the median hospital stay was 18 days (1–96). Five patients (45%) developed at least 1 postoperative complication and, of these, 4 (36%) were infections: Early death occurred in 1 patient (9%) and 3 (27%) had a late death.

We compared the patients who underwent valve replacement (n=16) and those whose intervention dealt with the pericardial window (n=11). We observed that the patients requiring a pericardial window were younger (21 vs 31 years, P=.008); had a shorter disease duration (5 vs 75 months, P=.01); their disease was more active at the time of the procedure (SLEDAI-2K: 12 vs 0, P=.001); they had higher anti-dsDNA titers (111.3 vs 16, P=.01); a higher percentage had low C3 and C4 (73% vs 29%, P=.04); they had lower albumin levels (2.3 vs 3.7g/dL, P=.08); they were more likely to undergo urgent surgery (82% vs 38%, P=.04); the operative time was shorter (1.3 vs 4.3h, P<.0001); and there was less bleeding (30 vs 850mL, P=.0002). No differences were observed in postoperative complications. The clinical associations in the patients who underwent the intervention for the pericardial window included: age (OR 0.86; 95% CI 0.74–0.98, P=.03) and disease activity according to the SLEDAI-2K (OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.02–1.34, P=.01).

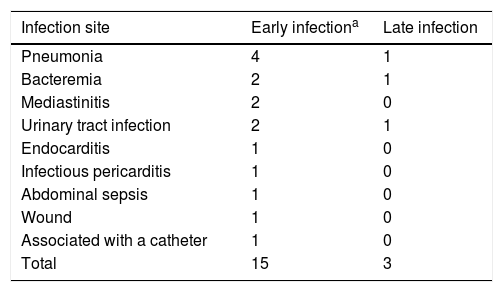

Early and Late Postoperative ComplicationsNineteen patients (63%) had at least 1 postoperative complication. Infections were most prevalent, occurring in 12 patients (40%); in all, 15 infectious events were recorded (12 early and 3 late). Three patients developed septic shock (2 early and 1 late); there were 3 patients with early cardiogenic shock and 3 cases of bleeding (2 early and 1 late); 2 required surgical reintervention (1 early and 1 late). Late thrombosis, late tamponade, early heart block and late valve failure occurred in 1 patient, respectively.

Aortic cross-clamp time of ≥76min was associated with the presence of at least 1 postoperative complication (OR 6.4; 95% CI 1.1–35.4, P=.03).

Table 4 shows the early and late sites of infection. The microorganisms isolated were:

Main Sites of Infection.

| Infection site | Early infectiona | Late infection |

|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | 4 | 1 |

| Bacteremia | 2 | 1 |

| Mediastinitis | 2 | 0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 | 1 |

| Endocarditis | 1 | 0 |

| Infectious pericarditis | 1 | 0 |

| Abdominal sepsis | 1 | 0 |

| Wound | 1 | 0 |

| Associated with a catheter | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 15 | 3 |

Listeria monocytogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Citrobacter amalonaticus, oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus auricularis, pericardial tuberculosis, Enterococcus, Candida parapsilosis and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Mortality and CausesThere were 8 deaths (27%); 5 were early (17%) and 3 late (10%). The median of the days between surgery and death was 9.5 (range: 0–81). The causes of early death were heart failure (n=1), sepsis (n=1) and hemopericardium (n=1); those causing late death were sepsis (n=2) and uremia (n=1). In 5 of the patients who died, the indication was urgent surgery, in 2 it was emergent and in 1 elective (P=.06 for emergent surgery).

We found no association between mortality and the presence of at least 1 postoperative complication (OR 3; 95% CI 0.9–18.2, P=.23). Those who died were 4 patients with pericardial window (2 of them emergent), 3 who underwent valve replacement and 1 with atrial thrombectomy.

Histopathological FindingsThe main histopathological findings in the 16 patients who underwent valve replacement were: myxoid degeneration (n=5), fibrosis (n=5), Libman-Sacks endocarditis (n=3) and endocarditis (n=3).

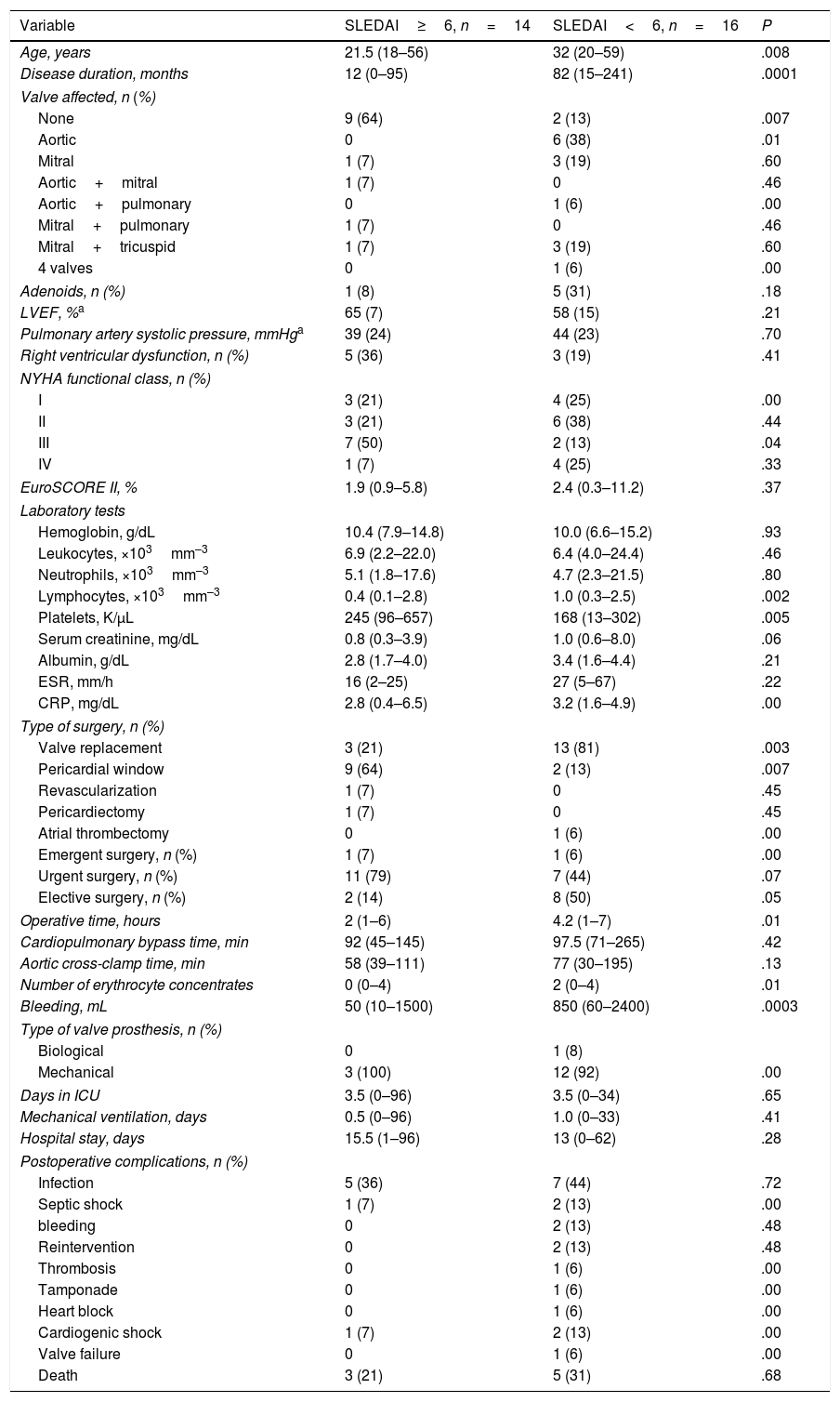

Postoperative Outcome in Terms of the Activity of Systemic Lupus ErythematosusWe compared the patients with SLEDAI-2K ≥ 6 (n=14) and SLEDAI-2K < 6 (n=14) at the time of surgery. The patients with higher activity were younger (21.5 vs 32 years, P=.008); had a shorter duration of SLE (12 vs 82 months, P=.001); had less valve involvement according to echocardiography (64% vs 13%, P=.007); NYHA functional class III (50% vs 13%, P=.04); less likelihood of elective surgery (14% vs 50%, P=.05); more accentuated lymphopenia (0.4 vs 1.0×103mm–3, P=.002); and a higher platelet count (245 vs 168K/μL, P=.005), when compared with patients with lower activity. In patients with higher activity, pericardial window was performed more frequently (64% vs 13%, P=.007); the operative time was shorter (2 vs 4.2h, P=.01); and there was less bleeding (50 vs 850mL, P=.0003).

The clinical associations in patients with active SLE were: pericardial window (OR 12.6; 95% CI 1.9–79, P=.007); lymphopenia ≤ 1200 (OR 10.1; 95% CI 1.05–97, P=.04); age ≤ 30 years (OR 7.7; 95% CI 1.2–46.3; P=.02); and NYHA class III (OR 7.0; 95% CI 1.1–42, P=.03). A duration of the disease≤1 year showed no association (OR 1.0; 95% CI 0.17–1.06, P=.06).

These results are summarized in Table 5.

Postoperative Outcome in Accordance With the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI-2K) Activity Index.

| Variable | SLEDAI≥6, n=14 | SLEDAI<6, n=16 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 21.5 (18–56) | 32 (20–59) | .008 |

| Disease duration, months | 12 (0–95) | 82 (15–241) | .0001 |

| Valve affected, n (%) | |||

| None | 9 (64) | 2 (13) | .007 |

| Aortic | 0 | 6 (38) | .01 |

| Mitral | 1 (7) | 3 (19) | .60 |

| Aortic+mitral | 1 (7) | 0 | .46 |

| Aortic+pulmonary | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Mitral+pulmonary | 1 (7) | 0 | .46 |

| Mitral+tricuspid | 1 (7) | 3 (19) | .60 |

| 4 valves | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Adenoids, n (%) | 1 (8) | 5 (31) | .18 |

| LVEF, %a | 65 (7) | 58 (15) | .21 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure, mmHga | 39 (24) | 44 (23) | .70 |

| Right ventricular dysfunction, n (%) | 5 (36) | 3 (19) | .41 |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | |||

| I | 3 (21) | 4 (25) | .00 |

| II | 3 (21) | 6 (38) | .44 |

| III | 7 (50) | 2 (13) | .04 |

| IV | 1 (7) | 4 (25) | .33 |

| EuroSCORE II, % | 1.9 (0.9–5.8) | 2.4 (0.3–11.2) | .37 |

| Laboratory tests | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 10.4 (7.9–14.8) | 10.0 (6.6–15.2) | .93 |

| Leukocytes, ×103mm–3 | 6.9 (2.2–22.0) | 6.4 (4.0–24.4) | .46 |

| Neutrophils, ×103mm–3 | 5.1 (1.8–17.6) | 4.7 (2.3–21.5) | .80 |

| Lymphocytes, ×103mm–3 | 0.4 (0.1–2.8) | 1.0 (0.3–2.5) | .002 |

| Platelets, K/μL | 245 (96–657) | 168 (13–302) | .005 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.3–3.9) | 1.0 (0.6–8.0) | .06 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.8 (1.7–4.0) | 3.4 (1.6–4.4) | .21 |

| ESR, mm/h | 16 (2–25) | 27 (5–67) | .22 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 2.8 (0.4–6.5) | 3.2 (1.6–4.9) | .00 |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |||

| Valve replacement | 3 (21) | 13 (81) | .003 |

| Pericardial window | 9 (64) | 2 (13) | .007 |

| Revascularization | 1 (7) | 0 | .45 |

| Pericardiectomy | 1 (7) | 0 | .45 |

| Atrial thrombectomy | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Emergent surgery, n (%) | 1 (7) | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Urgent surgery, n (%) | 11 (79) | 7 (44) | .07 |

| Elective surgery, n (%) | 2 (14) | 8 (50) | .05 |

| Operative time, hours | 2 (1–6) | 4.2 (1–7) | .01 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time, min | 92 (45–145) | 97.5 (71–265) | .42 |

| Aortic cross-clamp time, min | 58 (39–111) | 77 (30–195) | .13 |

| Number of erythrocyte concentrates | 0 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | .01 |

| Bleeding, mL | 50 (10–1500) | 850 (60–2400) | .0003 |

| Type of valve prosthesis, n (%) | |||

| Biological | 0 | 1 (8) | |

| Mechanical | 3 (100) | 12 (92) | .00 |

| Days in ICU | 3.5 (0–96) | 3.5 (0–34) | .65 |

| Mechanical ventilation, days | 0.5 (0–96) | 1.0 (0–33) | .41 |

| Hospital stay, days | 15.5 (1–96) | 13 (0–62) | .28 |

| Postoperative complications, n (%) | |||

| Infection | 5 (36) | 7 (44) | .72 |

| Septic shock | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | .00 |

| bleeding | 0 | 2 (13) | .48 |

| Reintervention | 0 | 2 (13) | .48 |

| Thrombosis | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Tamponade | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Heart block | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | .00 |

| Valve failure | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Death | 3 (21) | 5 (31) | .68 |

Values expressed as medians (minimum-maximal) or n (%).

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; ICU, intensive care unit; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, classification of heart failure of the New York Heart Association.

We compared the patients taking doses of prednisone ≥10mg/d (n=14) and <10mg/d (n=16). The first group had a higher SLEDAI-2K (6 vs 0, P=.01), higher leukocyte and platelet counts (8.4 vs 5.5×103mm–3, P=.04); 263 vs 191K/μL, P=.02, respectively), compared with those taking a lower prednisone dose. We found no differences between the groups in the other variables studied.

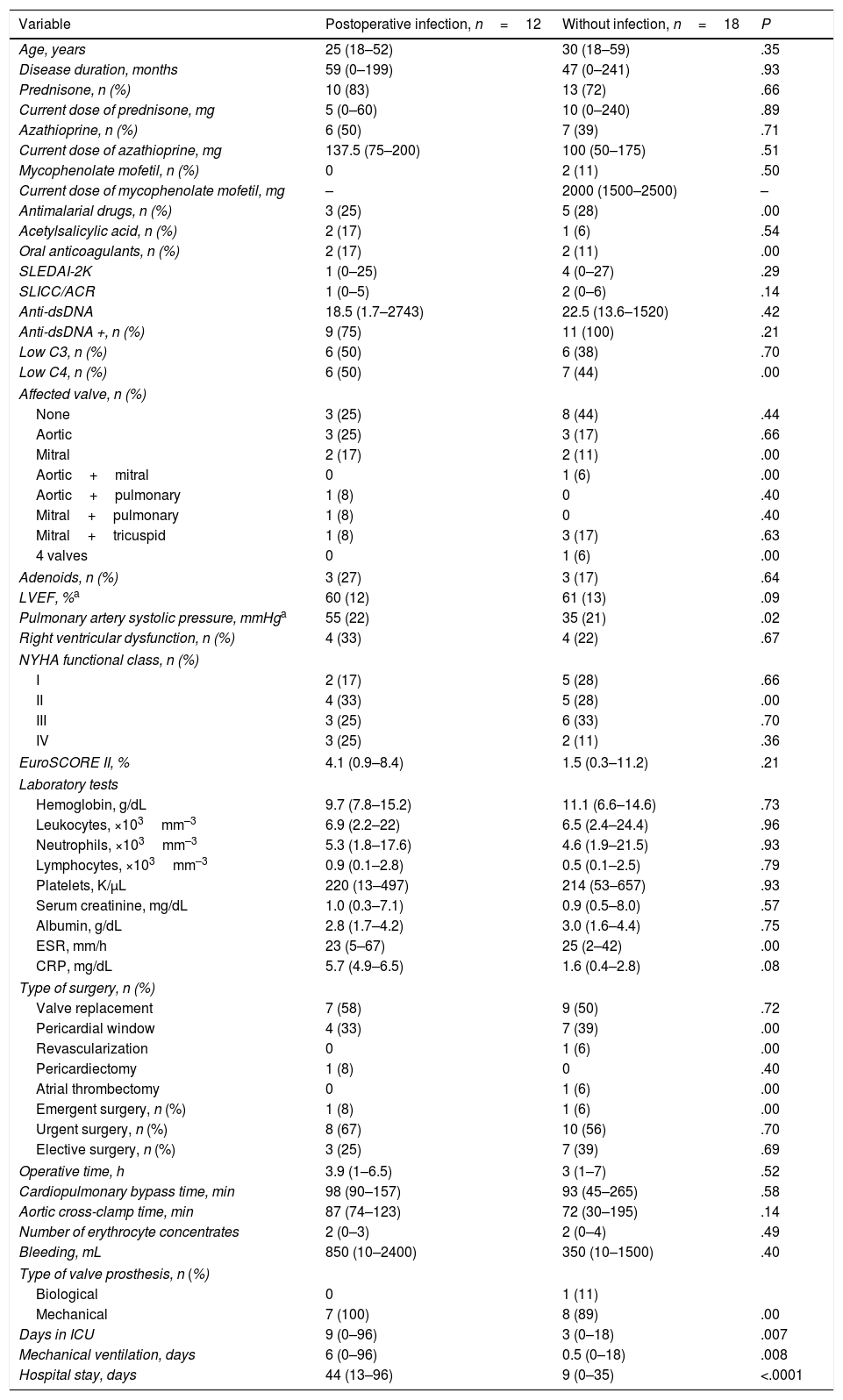

Patients With and Without Postoperative InfectionsWe compared patients with infections (n=12) and patients without these complications (n=18). The first group had a higher pulmonary artery systolic pressure (55 vs 35mmHg, P=.02); a longer stay in the ICU (9 vs 3 days, P=.007); longer mechanical ventilation time (6 vs 0.5 days, P=.008); and a longer hospital stay (44 vs 9 days, P=.0001), with respect to the patients without infections.

The clinical associations in the infected patients were: hospital stay ≥2 weeks (OR 54.9; 95% CI 5.0–602.1, P=.001); ≥10 days in ICU (OR 20, 95% CI 1.6–171.7, P=.01); ≥5 days of mechanical ventilation (OR 16.9; 95% CI 1.6–171.7, P=.01); and pulmonary artery systolic pressure ≥ 50mmHg (OR 7.8; 95% CI 1.4–41.2, P=.01). Table 6 summarizes the above data.

Characteristics of the Patients With and Without Postoperative Infections.

| Variable | Postoperative infection, n=12 | Without infection, n=18 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 25 (18–52) | 30 (18–59) | .35 |

| Disease duration, months | 59 (0–199) | 47 (0–241) | .93 |

| Prednisone, n (%) | 10 (83) | 13 (72) | .66 |

| Current dose of prednisone, mg | 5 (0–60) | 10 (0–240) | .89 |

| Azathioprine, n (%) | 6 (50) | 7 (39) | .71 |

| Current dose of azathioprine, mg | 137.5 (75–200) | 100 (50–175) | .51 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil, n (%) | 0 | 2 (11) | .50 |

| Current dose of mycophenolate mofetil, mg | – | 2000 (1500–2500) | – |

| Antimalarial drugs, n (%) | 3 (25) | 5 (28) | .00 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid, n (%) | 2 (17) | 1 (6) | .54 |

| Oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 2 (17) | 2 (11) | .00 |

| SLEDAI-2K | 1 (0–25) | 4 (0–27) | .29 |

| SLICC/ACR | 1 (0–5) | 2 (0–6) | .14 |

| Anti-dsDNA | 18.5 (1.7–2743) | 22.5 (13.6–1520) | .42 |

| Anti-dsDNA +, n (%) | 9 (75) | 11 (100) | .21 |

| Low C3, n (%) | 6 (50) | 6 (38) | .70 |

| Low C4, n (%) | 6 (50) | 7 (44) | .00 |

| Affected valve, n (%) | |||

| None | 3 (25) | 8 (44) | .44 |

| Aortic | 3 (25) | 3 (17) | .66 |

| Mitral | 2 (17) | 2 (11) | .00 |

| Aortic+mitral | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Aortic+pulmonary | 1 (8) | 0 | .40 |

| Mitral+pulmonary | 1 (8) | 0 | .40 |

| Mitral+tricuspid | 1 (8) | 3 (17) | .63 |

| 4 valves | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Adenoids, n (%) | 3 (27) | 3 (17) | .64 |

| LVEF, %a | 60 (12) | 61 (13) | .09 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure, mmHga | 55 (22) | 35 (21) | .02 |

| Right ventricular dysfunction, n (%) | 4 (33) | 4 (22) | .67 |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | |||

| I | 2 (17) | 5 (28) | .66 |

| II | 4 (33) | 5 (28) | .00 |

| III | 3 (25) | 6 (33) | .70 |

| IV | 3 (25) | 2 (11) | .36 |

| EuroSCORE II, % | 4.1 (0.9–8.4) | 1.5 (0.3–11.2) | .21 |

| Laboratory tests | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.7 (7.8–15.2) | 11.1 (6.6–14.6) | .73 |

| Leukocytes, ×103mm–3 | 6.9 (2.2–22) | 6.5 (2.4–24.4) | .96 |

| Neutrophils, ×103mm–3 | 5.3 (1.8–17.6) | 4.6 (1.9–21.5) | .93 |

| Lymphocytes, ×103mm–3 | 0.9 (0.1–2.8) | 0.5 (0.1–2.5) | .79 |

| Platelets, K/μL | 220 (13–497) | 214 (53–657) | .93 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0 (0.3–7.1) | 0.9 (0.5–8.0) | .57 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 2.8 (1.7–4.2) | 3.0 (1.6–4.4) | .75 |

| ESR, mm/h | 23 (5–67) | 25 (2–42) | .00 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 5.7 (4.9–6.5) | 1.6 (0.4–2.8) | .08 |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | |||

| Valve replacement | 7 (58) | 9 (50) | .72 |

| Pericardial window | 4 (33) | 7 (39) | .00 |

| Revascularization | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Pericardiectomy | 1 (8) | 0 | .40 |

| Atrial thrombectomy | 0 | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Emergent surgery, n (%) | 1 (8) | 1 (6) | .00 |

| Urgent surgery, n (%) | 8 (67) | 10 (56) | .70 |

| Elective surgery, n (%) | 3 (25) | 7 (39) | .69 |

| Operative time, h | 3.9 (1–6.5) | 3 (1–7) | .52 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time, min | 98 (90–157) | 93 (45–265) | .58 |

| Aortic cross-clamp time, min | 87 (74–123) | 72 (30–195) | .14 |

| Number of erythrocyte concentrates | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–4) | .49 |

| Bleeding, mL | 850 (10–2400) | 350 (10–1500) | .40 |

| Type of valve prosthesis, n (%) | |||

| Biological | 0 | 1 (11) | |

| Mechanical | 7 (100) | 8 (89) | .00 |

| Days in ICU | 9 (0–96) | 3 (0–18) | .007 |

| Mechanical ventilation, days | 6 (0–96) | 0.5 (0–18) | .008 |

| Hospital stay, days | 44 (13–96) | 9 (0–35) | <.0001 |

Values expressed as medians (minimum-maximal) or n (%).

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EuroSCORE II, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; ICU, intensive care unit; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, classification of heart failure of the New York Heart Association; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index; SLICC/ACR, Systemic Lupus International Collaborative Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index.

In our study, the procedure most frequently employed was valve replacement, followed by pericardial window. The most prevalent complication was infection, and the mortality rate was 8 patients (27%). The associations in patients with active SLE were pericardial window, lymphopenia ≤1200, age ≤ 30 years and NYHA class III; whereas postoperative infections were associated with a longer hospital stay and pulmonary artery hypertension.

In our population, the prevalence of serositis at the onset of SLE, like myocarditis and/or pericarditis over the course of the disease, was similar to that reported elsewhere.2,5,17–19 The mitral valve was that most frequently affected, as has been reported previously.5,6,17,18 We encountered a higher prevalence of valve defects by echocardiogram (63%), compared with earlier descriptions (40%).4 This is due to the fact that echocardiogram was performed in the patients prior to surgery, the reason why we also detected a higher prevalence of affected valves. We found no association between valve damage and anticardiolipin antibodies or other antiphospholipid antibodies. This could be due to the number of patients studied, since not all of them had had antibody determination at the time of the diagnosis of SLE, and to the fact that only 1 patient had secondary APS.

Among the factors related to SLE, the activity index and the accumulated damage have been associated with cardiac damage. The demographic factors (ethnic group and low socioeconomic level), have also been described in multiethnic cohorts that include Mexican patients with SLE.2 The hospital stay in our study was similar to that reported in a study on mitral surgery in SLE patients (12.6 days).20

In the present study, patients with active SLE had a more favorable outcome (shorter operative time and less bleeding). This finding was related to the predominance of pericardial window in these patients. The comparative analysis of the patients who underwent valve replacement with respect to those in whom pericardial window was carried out suggests that the patients who underwent pericardial window had a clinical profile characterized by lower age, a shorter disease duration, clinical and serological activity, and hypoalbuminemia, without differing from the patients who underwent valve replacement in terms of the incidence of complications.

In a study in patients without SLE who had cardiac surgery, a preoperative lymphocyte count ≤1500 cells/μL was identified as a prognostic factor of postoperative morbidity and mortality.21 However, in our study, lymphopenia was associated only with increased SLE activity.

We found no association between the use of glucocorticoids (prednisone ≥10mg/d) and postoperative adverse events. This finding can be explained because the prednisone dose was low in all the patients. The role of glucocorticoids in cardiovascular disease related to SLE is controversial, since these drugs are directly atherogenic and increase the risk of mitral regurgitation; they prevent premature atherosclerosis indirectly by controlling SLE activity.4,6,18 It can be hypothesized that low doses of glucocorticoids have a protective effect against cardiac manifestations.

Infections, especially pneumonias, were the most frequent postoperative complications in our study, despite the fact that the median prednisone dose was low (6mg/d). In patients without SLE who underwent cardiac surgery, the risk factors for postoperative pulmonary complications were different (e.g., older age, preoperative congestive heart disease, duration of cardiopulmonary bypass, phrenic nerve injury and postoperative acute kidney injury).22

The rate of mortality in patients with SLE and cardiac involvement is high. A study in Brazil reported a mortality of 17% in 48 patients with a median follow-up of 7.2 years,17 and another of 17% in 202 patients in the cohort from the Grupo Latinoamericano de Estudio de Lupus (Latin American Group for the Study of Lupus), with a median follow-up of 5 years.2 A multicenter study with 621 patients who underwent mitral valve surgery found a mortality <4%20; whereas, in our study, the early mortality rate was high (17%), despite a low preoperative EuroSCORE. These findings suggest that the traditional cardiovascular risk scores underestimate the risk of death in patients with SLE, possibly because these patients are not characterized by the risk factors considered by these scores (e.g., older age, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neurological disorders, recent history of cardiac surgery, ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension).

The main causes of death in our cohort coincide with those described in previous studies.1,17 Rather than the outcomes of valve surgery for endocarditis,23 we encountered a slight trend toward death in patients whose intervention was emergent.

We require strategies for the early detection of cardiac manifestations in SLE, including clinical and echocardiographic data. When cardiac surgery is required, it should be done with a multidisciplinary preoperative protocol that considers traditional cardiovascular risk factors as well as those associated with SLE.

The present study has certain limitations. One of them is the retrospective design and the inclusion of patients transferred from a tertiary center that had more severe disease, a fact that makes extrapolation of the results more difficult. Moreover, the inclusion of a control group was limited by the disparity in terms of age, sex and comorbidities in patients without SLE who underwent cardiac surgery in our center. The size of the sample limited the performance of multivariate analysis. The failure to determine antiphospholipid antibodies in all of the patients at the time of the diagnosis of SLE could explain the low prevalence of secondary APS in patients with valve disease.

The main strength of the study is that it constitutes the report with the highest number of SLE patients who underwent cardiac surgery in a single center. It stresses the vulnerability of these patients and the need to devise pre- and postoperative strategies to reduce complications and mortality. On the other hand, it analyzes both the clinical variables related to the disease and the surgical variables associated with the procedure.

In conclusion, cardiac surgery in SLE patients is associated with postoperative complications, mainly infectious, and a high mortality rate, although the population is young and has a low prevalence of traditional risk factors. The preoperative risk scores that are routinely used are not designed to estimate risk in these patients. Therefore, it is necessary to perform prospective studies with a larger number of patients to establish the appropriate scores that enable us to assess the postoperative outcomes in patients with SLE.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Tejeda-Maldonado J, Quintanilla-González L, Galindo-Uribe J, Hinojosa-Azaola A. Cirugía cardiaca en pacientes con lupus eritematoso sistémico: características clínicas y desenlaces. Reumatol Clin. 2018;14:269–277.