Tuberous sclerosis, also called Bourneville Pringle disease, is a phakomatosis with potential dermal, nerve, kidney and lung damage. It is characterized by the development of benign proliferations in many organs, which result in different clinical manifestations. It is associated with the mutation of two genes: TSC1 (hamartin) and TSC2 (tuberin), with the change in the functionality of the complex target of rapamycin (mTOR). MTOR activation signal has been recently described in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and its inhibition could be beneficial in patients with lupus nephritis.

We report the case of a patient who began with clinical manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) 30 years after the onset of SLE with severe renal disease (tipe IV nephritis) who improved after treatment with iv pulses of cyclophosphamide.

We found only two similar cases in the literature, and hence considered the coexistence of these two entities of great interest.

La esclerosis tuberosa (ET), también llamada enfermedad de Pringle Bourneville, es una facomatosis con posible afectación dérmica, neurológica, renal y pulmonar. Se caracteriza por el desarrollo de proliferaciones benignas en numerosos órganos, que dan lugar a las diferentes manifestaciones clínicas. Se asocia a la mutación de 2 genes: TSC1 (hamartina) y TSC2 (tuberina), con la alteración funcional del complejo diana de la rapamicina (mTOR). La activación de la señal mTOR ha sido descrita recientemente en el lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES), y su inhibición podría resultar beneficiosa en pacientes con nefritis lúpica. Presentamos el caso de una paciente que 30 años después del inicio de LES con afectación renal grave (glomerulonefritis tipo IV), resuelta con pulsos intravenosos de ciclofosfamida, comenzó con manifestaciones clínicas del complejo esclerosis tuberosa (CET).

Consideramos de interés la coexistencia de estas 2 entidades, ya que solo hemos encontrado 2 casos similares en la literatura.

The tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant disease, with variable expression and multisystem involvement, characterized by the growth of benign tumors referred to as hamartomas (neurofibromas and angiofibromas). The organs most frequently affected are brain, skin, kidneys, eyes, heart and lungs. The symptoms of TS may be present at birth or appear at later ages. The severity of the disorder varies widely, ranging from mild forms to severely disabling disease.

The prevalence ranges between 1/6000 and 1/10000 live births1. It is the result of the mutation of 1 of 2 genes, TSC1 (encoding hamartin) or TSC2 (encoding tuberin), which leads to a change in the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), characterized by continuous and deficient activation. A possible role of the alteration of the mTOR complex in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has also been reported. As the mTOR pathway has been found to be activated in SLE, its inhibition would benefit patients with lupus nephritis.

Patients with TSC would have a high risk of developing SLE, since the mTOR pathway plays a key role in T cells and can activate autoimmunity.2 Moreover, using rapamycin to block the mTOR signal has been effective in the treatment of SLE in humans.3 However, to our knowledge, only 2 cases of the association of TSC and SLE have been reported.4,5 Both patients were young women diagnosed with TS, who subsequently developed SLE with severe renal involvement. One died, after experiencing seizures and developing sepsis, gastric bleeding and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage during treatment to induce remission.5 The authors describing the latter case suggest that the activation of mTOR by the mutations involved in TSC might have led to the activation of the immune system and to the development of severe SLE. In contrast, although our patient's disease presented with the signs and symptoms of SLE and severe lupus nephritis, her outcome was favorable and she has achieved complete remission of her renal condition.

Case ReportThe patient was a 47-year-old woman who, at the age of 14 years, had been diagnosed with SLE on the basis of joint disease (polyarthritis), accompanied by mucocutaneous (aphthous stomatitis, malar rash and photosensitivity), renal (nephrotic syndrome) and hematologic (hemolytic anemia, leukopenia, lymphopenia) manifestations, hypocomplementemia and serological evidence (antinuclear antibody titer, 1:2560 [homogeneous pattern], anti-DNA antibody level, 62IU/mL). The renal involvement was defined by biopsy as diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis (World Health Organization type IV). She was treated with high-dose glucocorticoids (1mg/kg/day) and 6 cyclophosphamide pulses/month (750mg/m2 body surface area) to induce remission, followed by 1 cyclophosphamide pulse every 3 months for 2 years, with no complications. Since then, the patient has continued to take hydroxychloroquine and low-dose glucocorticoids. Her renal function has remained normal, and she has had no further serious manifestations of SLE or significant laboratory abnormalities, including complement levels and cell counts. She still tests positive for antinuclear antibodies, at a titer of 1:640, and has an anti-double-stranded DNA antibody level (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA]) of 18IU/mL (slightly over the upper normal limit of 15IU/mL).

A biopsy of the skin lesions performed in 2000 was consistent with pigmented dermatofibromas.

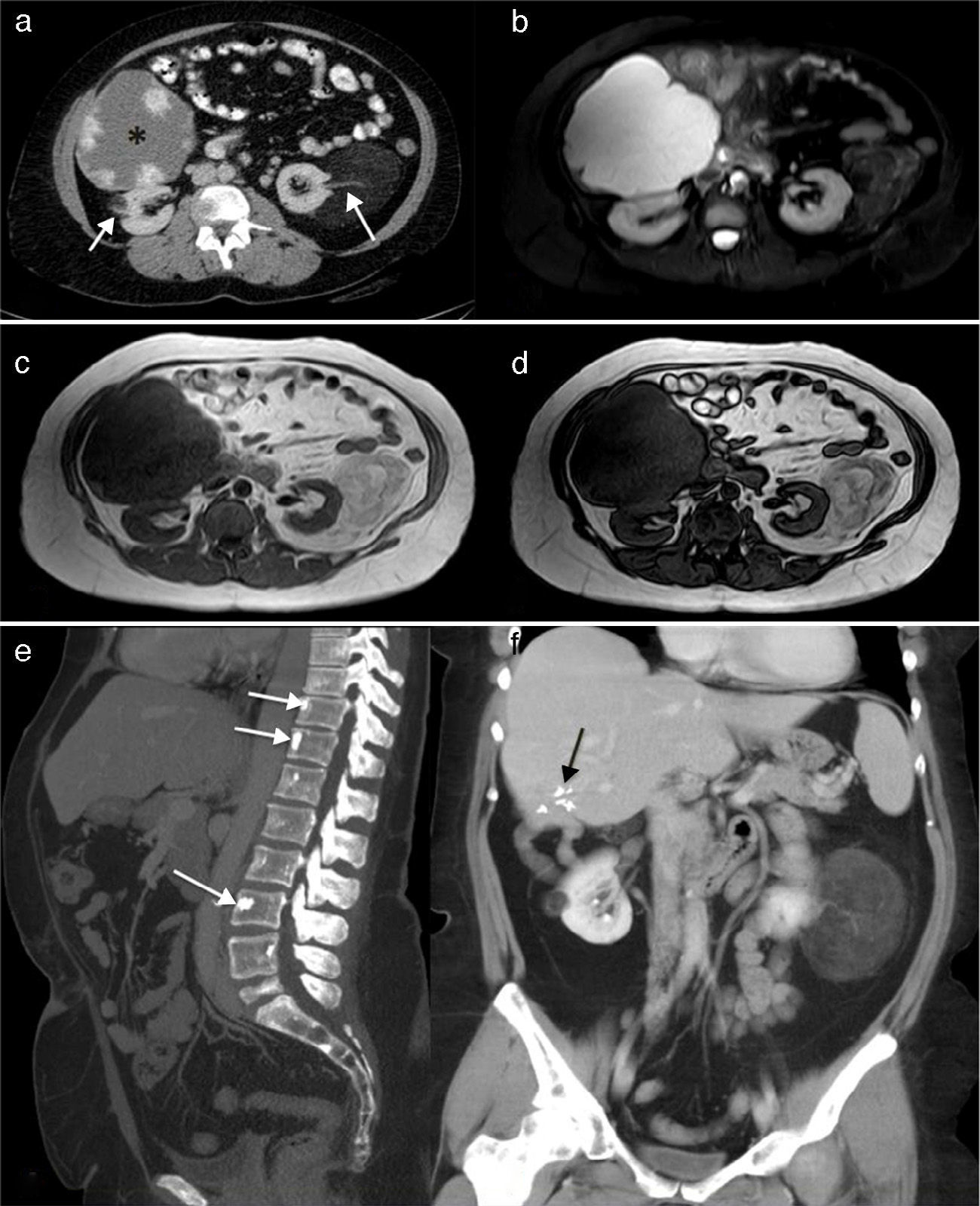

In February 2012, at the age of 44 years, with nothing notable in her obstetric history (no miscarriages and a normal pregnancy and delivery of a healthy daughter), she presented with heavy intermenstrual bleeding secondary to uterine myomas. Bilateral renal angiomyolipomas, a large hepatic hemangioma, rectal polyps and bone islands in axial skeleton were incidental findings on imaging studies (Fig. 1).

(a) Renal computed tomography (CT) showing a giant hepatic hemangioma (*) and bilateral low-density renal angiomyolipomas, similar to fat and the vascular pedicle (arrows). (b) Axial short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) images. The hepatic hemangioma is markedly hyperintense and the renal angiomas show low signal intensity with a few hyperintense areas on the left that represent the tumor vascularization. (c and d) T1-weighted gradient echo images in phase and reversed phase, respectively, showing the left renal angiomyolipomas with an intensity similar to fat, and hypointense areas in its interior that correspond to the vascular structures. The reversed phase image (d) shows that the signal of part of the tumor is canceled out because of the fat content. (e) Sagittal maximal intensity projection (MIP) reconstruction of CT images, showing a few vertebral bodies corresponding to bone islands (arrows). (f) Coronal MIP reconstruction of CT images. The hepatic hemangioma has been resected and the black arrows indicate the clips that remained after surgery. The 2 renal angiomyolipomas are clearly seen.

The presence of renal angiomyolipomas, together with facial angiofibromas (Fig. 2), 2 of the major criteria, led to the diagnosis of TSC; in addition, the patient had multiple dental enamel pits, hamartomatous rectal polyps and bone cysts (the latter being considered minor criteria), resulting in a definitive diagnosis according to the criteria for TSC (Table 1).6 She has never had seizures or other neurological manifestations. Since the diagnosis, she is being treated with everolimus and has not experienced any secondary effects or worsening of SLE.

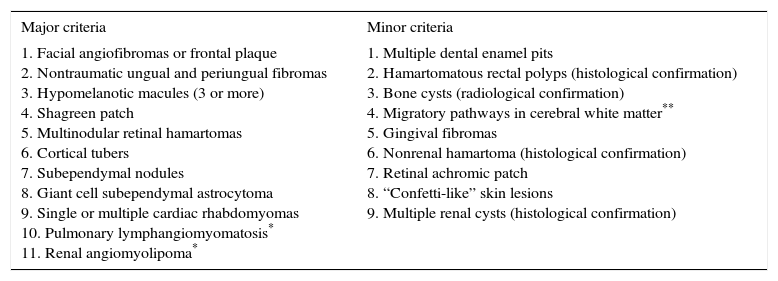

Diagnostic Criteria Corresponding to Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC)6

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Facial angiofibromas or frontal plaque 2. Nontraumatic ungual and periungual fibromas 3. Hypomelanotic macules (3 or more) 4. Shagreen patch 5. Multinodular retinal hamartomas 6. Cortical tubers 7. Subependymal nodules 8. Giant cell subependymal astrocytoma 9. Single or multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas 10. Pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis* 11. Renal angiomyolipoma* | 1. Multiple dental enamel pits 2. Hamartomatous rectal polyps (histological confirmation) 3. Bone cysts (radiological confirmation) 4. Migratory pathways in cerebral white matter** 5. Gingival fibromas 6. Nonrenal hamartoma (histological confirmation) 7. Retinal achromic patch 8. “Confetti-like” skin lesions 9. Multiple renal cysts (histological confirmation) |

Definitive diagnosis of TSC: 2 major criteria or 1 major and 2 minor criteria.

Probable diagnosis: 1 major and 1 minor criterion.

Possible diagnosis: 1 major criterion or 2 or more minor criteria.

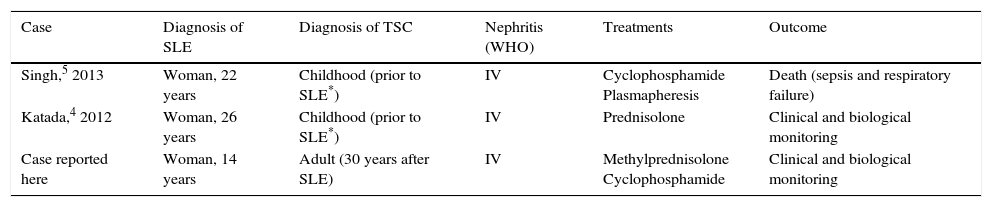

Our patient, like the 2 whose cases have been published to date,4,5 presented with severe renal involvement (diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis) as the initial manifestation of SLE. Whereas the diagnosis of TSC preceded that of SLE in the other 2 cases, in ours, the clinical signs of TSC were detected 30 years after the diagnosis of SLE. Table 2 summarizes the major features of the 3 cases.

Summary of the Major Features of the Three Cases.

| Case | Diagnosis of SLE | Diagnosis of TSC | Nephritis (WHO) | Treatments | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singh,5 2013 | Woman, 22 years | Childhood (prior to SLE*) | IV | Cyclophosphamide Plasmapheresis | Death (sepsis and respiratory failure) |

| Katada,4 2012 | Woman, 26 years | Childhood (prior to SLE*) | IV | Prednisolone | Clinical and biological monitoring |

| Case reported here | Woman, 14 years | Adult (30 years after SLE) | IV | Methylprednisolone Cyclophosphamide | Clinical and biological monitoring |

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TSC, tuberous sclerosis complex; WHO, World Health Organization.

Singh et al.5 reported a case of the association TSC/SLE with a catastrophic outcome due to serious complications (seizures, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, sepsis, etc.). According to the authors, the development of SLE in a patient with TSC, with activation of mTOR signaling, could produce an especially aggressive form of SLE, like that of the patient they describe. They suggest that, as a result of the altered mTOR signaling pathway, patients with TSC may have undetected autoimmunity and should undergo antinuclear antibody testing.

No genetic study was performed in the case we report. A definitive diagnosis of TSC was established because the patient met the clinical criteria (2 major and 3 minor criteria). The genetic criteria are not indispensable for the diagnosis.

The expressivity of TSC is highly variable, meaning that the manifestations and patient age at onset can differ widely.

On the other hand, we were unable to study the aforementioned gene sequences or their possible mutations to demonstrate the mechanisms that may have led to the association of the 2 diseases. However, despite the serious, florid manifestations of the 2 conditions observed in our patient, her course has been stable and she has responded well to conventional therapies, as also appears to have occurred in the case reported by Katada et al.4

ConclusionThe functional alteration of mTOR that occurs in TSC as a consequence of mutations in the TSC1 or TSC2 gene may play a role in the pathogenesis of SLE. Thus, we recommend that patients with TSC be tested for antibodies. The pathogenesis of SLE is complex and the coexistence of TSC does not necessarily imply a greater severity of SLE.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Carrasco Cubero C, Bejarano Moguel V, Fernández Gil MÁ, Álvarez Vega JL. Asociación lupus eritematoso sistémico y esclerosis tuberosa, un caso. Reumatol Clin. 2016;12:219–222.