To investigate the prevalence and associations with clinical manifestations of anti-P ribosomal antibodies in patients with juvenile-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

MethodsClinical and serological data of 30 patients with juvenile-onset SLE (age at onset younger than 16 years) were compared with data of 92 patients with adult-onset SLE. Symptoms occurring during the entire disease course were considered. Anti-P ribosomal antibodies were tested by ELISA.

ResultsAnti-P ribosomal antibodies were found significantly more often in pediatric-onset SLE patients (26.7% vs 6.5%; OR=5.21 [95% CI=1.6–16.5], P=.003). Alopecia (OR=10.11, 95% CI=1.25–97) and skin rash (non-discoid) (OR=4.1, 95% CI=1.25–13.89) were significantly associated with anti-P ribosomal antibodies.

ConclusionAnti-ribosomal P antibodies are more often found in patients with juvenile SLE. Alopecia and skin rash were the only clinical manifestations associated to anti-ribosomal P antibodies.

Determinar la prevalencia y correlación clínica de los anticuerpos antirribosomal P en lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) juvenil y compararlos con LES del adulto.

MétodosSe incluyeron en el estudio 30 pacientes con LES juvenil y 92 pacientes con LES del adulto. Consideramos LES de comienzo juvenil a todos aquellos pacientes que comenzaron su enfermedad antes de los 16 años. Se consideraron las manifestaciones clínicas y serológicas que presentaron los pacientes desde el diagnóstico hasta el momento de inclusión en el estudio (manifestaciones acumuladas). El anticuerpo antirribosomal P fue evaluado mediante la técnica de enzimo-inmunoensayo (ELISA).

ResultadosLa presencia de antirribosomal P fue significativamente mayor en el grupo de pacientes con LES juvenil comparado con LES del adulto (26,7% vs. 6,5%; OR=5.21 [95% CI=1,6–16,5], p=0,003). La alopecía (OR=10,11; 95% CI=1,25–97) y rash cutáneo (no discoide) (OR=4,1; 95% CI=1,25–13,89) fueron las únicas manifestaciones clínicas que se asociaron en forma estadísticamente significativa con la presencia del anticuerpo antirribosomal P.

ConclusiónEste estudio confirma una mayor prevalencia de anticuerpos antirribosomal P en pacientes con LES juvenil. La alopecia y el rash cutáneo fueros las únicas manifestaciones clínicas asociadas a la presencia de antirribosomal P.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that can affect virtually any organ or system, manifested clinically by exacerbations and remission periods and serologically characterized by the presence of antinuclear (ANA), anti-native DNA and anti-Sm antibodies. While it is more common in adults, 15%–20% of patients with SLE are first diagnosed before age 16.1–3 In patients with juvenile SLE, the highest incidence is between 12 and 14 years, being rare before.5,4

Anti-P ribosomal antibodies are directed against a family of phosphoproteins related to the 60s ribosomal subunit. The antibodies target 3 phosphoproteins P0 (38kDa), P1 (19kDa), and P2 (17kDa). Several clinical studies have observed clinical and serological differences between juvenile and adult SLE patients. The disease in patients with juvenile SLE is more severe, treatments are more aggressive and patients accumulate more damage during its progression.3,5 This is due to a higher incidence of renal and central nervous system involvement in patients under 16.1,6–9

A high prevalence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies has been reported in some series of patients with juvenile SLE,10,11 while other groups have found a higher prevalence of anti-native DNA, anti-Sm, and anti-nRNP.12,13 The anti-P ribosomal antibody prevalence in patients with SLE varies from 6% to 36% depending on ethnicity, age, and certain clinical variables.14–16

Anti-P ribosomal antibodies have been associated with the presence of nephritis,17–23 autoimmune hepatitis, and neurological involvement.24–27 Three studies assessed the prevalence and association with clinical manifestations of anti-P ribosomal antibodies in youths, but the findings from these studies differ.7,11,28

There are no data in the literature on the prevalence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies and their association with clinical manifestations in Argentine patients.

The objective of our study was to determine the prevalence and clinical correlation in Argentine patients of anti-P ribosomal antibodies in juvenile SLE compared with adult SLE. As a secondary objective we compared the cumulative clinical manifestations of juvenile and adult SLE.

Patients and MethodsPatientsAll patients included in this study met 4 or more classification criteria for SLE as proposed by the American College of Rheumatology 1997 revised criteria.29,30 We consider juvenile SLE patients those who began their disease before age 16. We included 30 patients with juvenile SLE and 92 adult SLE patients in the study, from 7 reference centers in Argentina: Center for Medical Education and Clinical Research Norberto Quirno (CEMIC), Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires, Acute General Hospital José Penna, Hospital de Clinicas José de San Martín, Acute General Hospital Juan Antonio Fernández, Hospital San Martín de La Plata, Buenos Aires British Hospital and Pediatrics Hospital Prof. Dr. Juan P. Garrahan.

Clinical DataA specific questionnaire was designed for the study, where clinical data based on the examination and review of the clinical history of the patient was collected. Clinical manifestations presented by patients from diagnosis to the time of inclusion in the study (cumulative events) were detailed. The following events were considered: Discoid rash, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, alopecia, malar rash, Raynaud's phenomenon, leukopenia, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, serositis, arthritis, psychosis, seizures, neuropathy, transverse myelitis, acute confusional state, glomerulonephritis, vasculitis, dry mouth, dry eyes. Information was obtained on treatments received from the time of diagnosis of the disease to inclusion in the study. Activity was calculated using the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) at the time of sample collection. Antibody results were also recorded during the patient's history (ANA, anti-DNA, anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB, anti-Sm, and anti-nRNP).

All participants signed informed consent; the study was conducted after approval by the ethics committees of each institution.

Specimen Collection and Laboratory DeterminationsBlood samples for determination of antibodies were taken in the participating centers, and were analyzed centrally in the CEMIC laboratory of Immunology and Rheumatology. Measurement of anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB, anti-Sm, and anti-nRNP antibodies was performed by double-diffusion technique. The anti-P ribosomal antibodies were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using as antigen, a purified protein from bovine and/or rabbit thymus (ImmunoVision, Inc.) absorbed at 0.5μg/well (Maxisorb polystyrene plate; Nunc). Samples were considered positive when values ≥11U. Measurement of anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB, anti-Sm, and anti-P ribosomal antibodies nRNP was performed simultaneously on all samples.

Statistical AnalysisQualitative variables are presented as numbers and percentages, and quantitative variables as mean/median and standard deviation/minimum and maximum values. To determine an association, we employed chi-square (χ2) or Fisher exact tests. To quantify the strength of association we used odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). For analysis of the SLEDAI in patients with positive and negative anti-P ribosomal antibodies and between adult vs juveniles, Wilcoxon and Mann–Whitney's tests were used. Significance was considered as a P<.05. Statistical analysis was performed using the Epi Info statistical package™ 7 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]).

ResultsDemographicsTwenty-four patients (80%) in the youth group and 81 (88%) adults had Caucasian ethnicity. Two (6.7%) of the patients with juvenile SLE and 6 (6.5%) patients in the adult SLE group were males. The mean age at diagnosis in patients with juvenile SLE was 12.67±3.56 and for adults, 30±11.46 years. The mean age of patients at the time of inclusion in the study was 22.9±8.4 and 39.76±12.37 years for the group of juvenile and adult SLE respectively; the average duration of the disease at the time of inclusion in the study was 10.63±7.16 years in youths and 9.36±7.75 years in adults.

Clinical manifestations and treatment received:

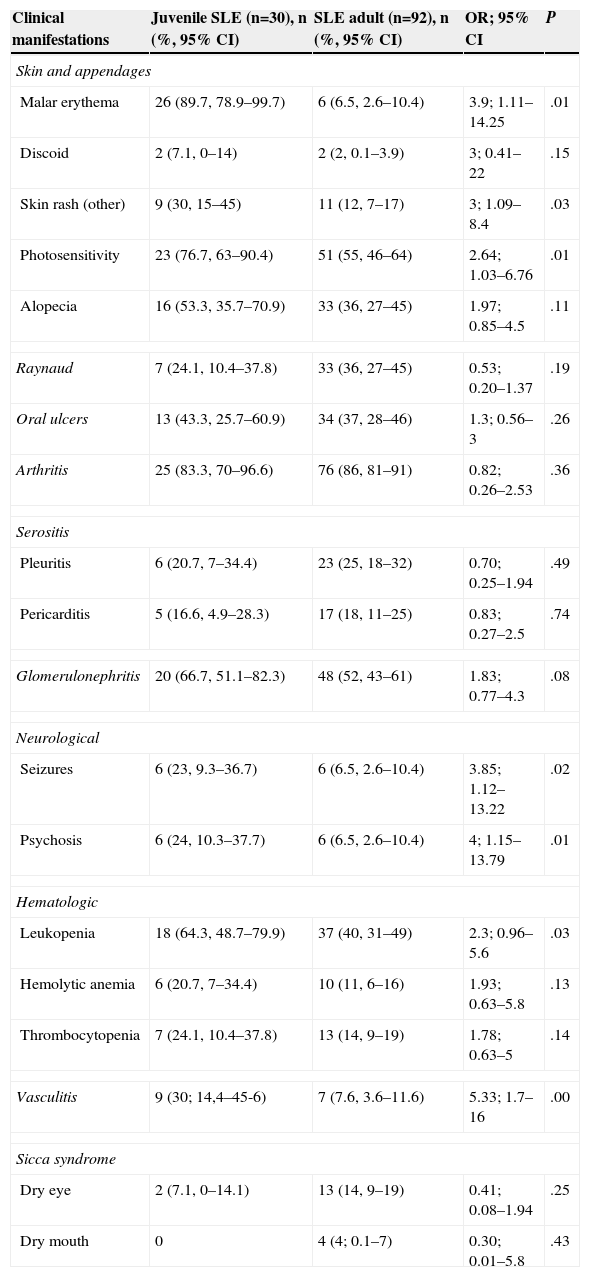

The prevalence of different clinical manifestations in both groups (adults and juveniles) is detailed in Table 1. Malar rash (OR=3.9, 95% CI=1.1–14.25), photosensitivity (OR=2.64, 95% CI=1.03–6.76), vasculitis (OR=5.33, 95% CI=1.7–16.0), non-discoid rash (OR=3.0, 95% CI=1.09–8.4) and neurological involvement: seizures (OR=3.85, 95% CI=1.12–13.22) and psychosis (OR=4, 95% CI=1.15–13.79) were found more frequently in the juvenile SLE. Five adult patients developed neurological manifestations (not in the ACR criteria): cognitive impairment in 3 patients, peripheral sensory polyneuropathy of the lower limbs in 1 patient and 1 patient with acute confusional state. No patient developed transverse myelitis or multiple mononeuritis.

Prevalence of Clinical Manifestations: Juvenile SLE Compared With Adult SLE.

| Clinical manifestations | Juvenile SLE (n=30), n (%, 95% CI) | SLE adult (n=92), n (%, 95% CI) | OR; 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin and appendages | ||||

| Malar erythema | 26 (89.7, 78.9–99.7) | 6 (6.5, 2.6–10.4) | 3.9; 1.11–14.25 | .01 |

| Discoid | 2 (7.1, 0–14) | 2 (2, 0.1–3.9) | 3; 0.41–22 | .15 |

| Skin rash (other) | 9 (30, 15–45) | 11 (12, 7–17) | 3; 1.09–8.4 | .03 |

| Photosensitivity | 23 (76.7, 63–90.4) | 51 (55, 46–64) | 2.64; 1.03–6.76 | .01 |

| Alopecia | 16 (53.3, 35.7–70.9) | 33 (36, 27–45) | 1.97; 0.85–4.5 | .11 |

| Raynaud | 7 (24.1, 10.4–37.8) | 33 (36, 27–45) | 0.53; 0.20–1.37 | .19 |

| Oral ulcers | 13 (43.3, 25.7–60.9) | 34 (37, 28–46) | 1.3; 0.56–3 | .26 |

| Arthritis | 25 (83.3, 70–96.6) | 76 (86, 81–91) | 0.82; 0.26–2.53 | .36 |

| Serositis | ||||

| Pleuritis | 6 (20.7, 7–34.4) | 23 (25, 18–32) | 0.70; 0.25–1.94 | .49 |

| Pericarditis | 5 (16.6, 4.9–28.3) | 17 (18, 11–25) | 0.83; 0.27–2.5 | .74 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 20 (66.7, 51.1–82.3) | 48 (52, 43–61) | 1.83; 0.77–4.3 | .08 |

| Neurological | ||||

| Seizures | 6 (23, 9.3–36.7) | 6 (6.5, 2.6–10.4) | 3.85; 1.12–13.22 | .02 |

| Psychosis | 6 (24, 10.3–37.7) | 6 (6.5, 2.6–10.4) | 4; 1.15–13.79 | .01 |

| Hematologic | ||||

| Leukopenia | 18 (64.3, 48.7–79.9) | 37 (40, 31–49) | 2.3; 0.96–5.6 | .03 |

| Hemolytic anemia | 6 (20.7, 7–34.4) | 10 (11, 6–16) | 1.93; 0.63–5.8 | .13 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 7 (24.1, 10.4–37.8) | 13 (14, 9–19) | 1.78; 0.63–5 | .14 |

| Vasculitis | 9 (30; 14,4–45-6) | 7 (7.6, 3.6–11.6) | 5.33; 1.7–16 | .00 |

| Sicca syndrome | ||||

| Dry eye | 2 (7.1, 0–14.1) | 13 (14, 9–19) | 0.41; 0.08–1.94 | .25 |

| Dry mouth | 0 | 4 (4; 0.1–7) | 0.30; 0.01–5.8 | .43 |

Patients used the following immunosuppressive therapy: methotrexate (MTX), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), azathioprine (AZA), cyclophosphamide (CF), glucocorticoids (prednisone or equivalent) >20mg; there were no statistically significant differences between adult and juvenile patients or between the patients positive or negative anti-P ribosomal antibodies (data not shown). Adult patients received hydroxychloroquine more frequently than juveniles (95.6% vs 83.3%; P=.025).

The SLEDAI score in the total population (adults and juveniles) was mean 3.89 (SD 4.68) in patients with juvenile SLE and 5.11 (SD 5.33) and 3.56 in adults (SD 4.44; P=.09).

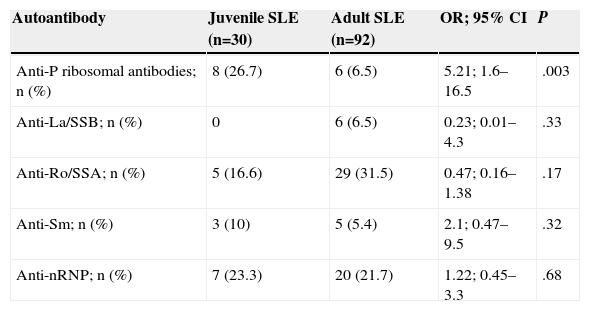

Prevalence of AntibodiesThe prevalence of antibodies is detailed in Table 2. Of the antibodies determined, the presence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies (OR=5.21, 95% CI=1.6–16.5) was significantly higher in the group of patients with juvenile SLE.

Prevalence of Autoantibodies in Patients With Juvenile SLE Compared to Adult SLE.

| Autoantibody | Juvenile SLE (n=30) | Adult SLE (n=92) | OR; 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-P ribosomal antibodies; n (%) | 8 (26.7) | 6 (6.5) | 5.21; 1.6–16.5 | .003 |

| Anti-La/SSB; n (%) | 0 | 6 (6.5) | 0.23; 0.01–4.3 | .33 |

| Anti-Ro/SSA; n (%) | 5 (16.6) | 29 (31.5) | 0.47; 0.16–1.38 | .17 |

| Anti-Sm; n (%) | 3 (10) | 5 (5.4) | 2.1; 0.47–9.5 | .32 |

| Anti-nRNP; n (%) | 7 (23.3) | 20 (21.7) | 1.22; 0.45–3.3 | .68 |

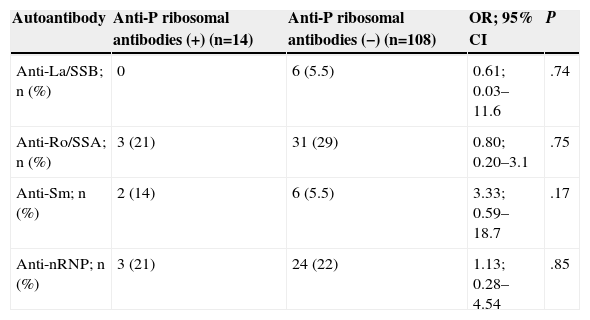

Table 3 shows the prevalence of other autoantibodies in patients with adult and juvenile SLE, according to whether they were positive or negative for anti-P ribosomal antibodies. The prevalence of all other autoantibodies was similar in both groups.

Prevalence of Other Autoantibodies in Patients With Positive and Negative Anti-P Ribosomal Antibodies.

| Autoantibody | Anti-P ribosomal antibodies (+) (n=14) | Anti-P ribosomal antibodies (−) (n=108) | OR; 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-La/SSB; n (%) | 0 | 6 (5.5) | 0.61; 0.03–11.6 | .74 |

| Anti-Ro/SSA; n (%) | 3 (21) | 31 (29) | 0.80; 0.20–3.1 | .75 |

| Anti-Sm; n (%) | 2 (14) | 6 (5.5) | 3.33; 0.59–18.7 | .17 |

| Anti-nRNP; n (%) | 3 (21) | 24 (22) | 1.13; 0.28–4.54 | .85 |

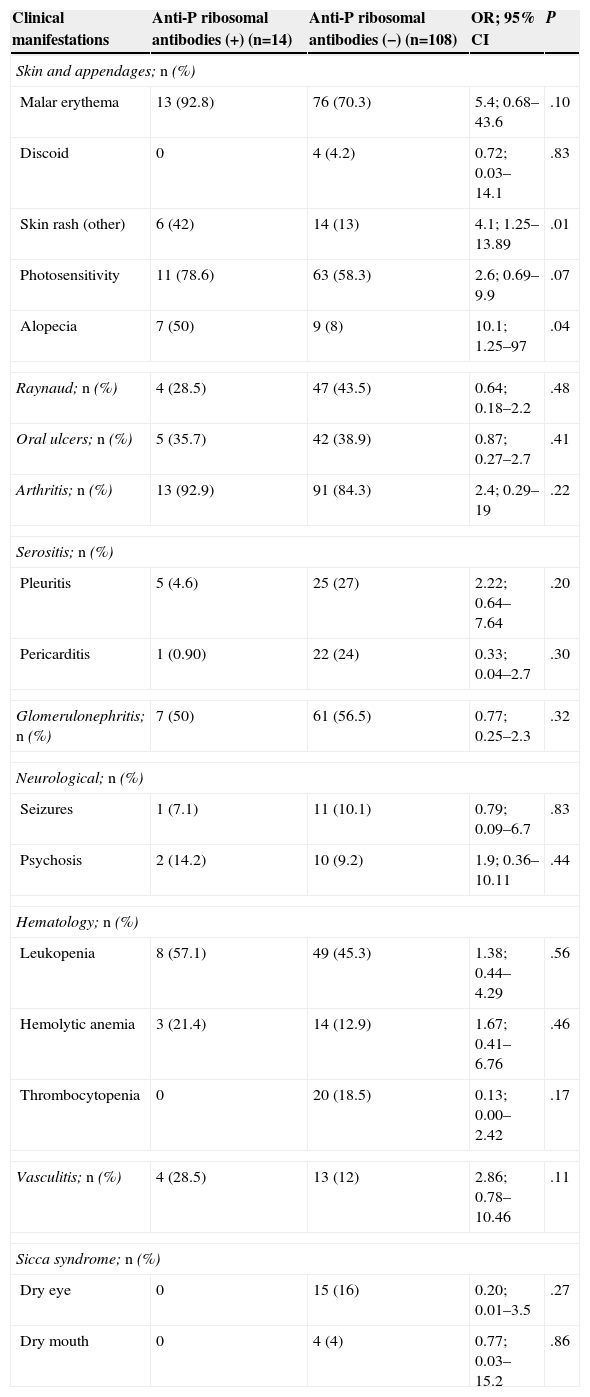

Table 4 shows the prevalence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies detailed according to the clinical manifestations. Alopecia (OR=10.11, 95% CI=1.25–97) and skin rash (non-discoid) (OR=4.1, 95% CI=1.25–13.89) were the only clinical manifestations that were significantly associated with the presence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies.

Differences in Clinical Manifestations Between Positive and Negative Anti-P Ribosomal Antibody-Patients.

| Clinical manifestations | Anti-P ribosomal antibodies (+) (n=14) | Anti-P ribosomal antibodies (−) (n=108) | OR; 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin and appendages; n (%) | ||||

| Malar erythema | 13 (92.8) | 76 (70.3) | 5.4; 0.68–43.6 | .10 |

| Discoid | 0 | 4 (4.2) | 0.72; 0.03–14.1 | .83 |

| Skin rash (other) | 6 (42) | 14 (13) | 4.1; 1.25–13.89 | .01 |

| Photosensitivity | 11 (78.6) | 63 (58.3) | 2.6; 0.69–9.9 | .07 |

| Alopecia | 7 (50) | 9 (8) | 10.1; 1.25–97 | .04 |

| Raynaud; n (%) | 4 (28.5) | 47 (43.5) | 0.64; 0.18–2.2 | .48 |

| Oral ulcers; n (%) | 5 (35.7) | 42 (38.9) | 0.87; 0.27–2.7 | .41 |

| Arthritis; n (%) | 13 (92.9) | 91 (84.3) | 2.4; 0.29–19 | .22 |

| Serositis; n (%) | ||||

| Pleuritis | 5 (4.6) | 25 (27) | 2.22; 0.64–7.64 | .20 |

| Pericarditis | 1 (0.90) | 22 (24) | 0.33; 0.04–2.7 | .30 |

| Glomerulonephritis; n (%) | 7 (50) | 61 (56.5) | 0.77; 0.25–2.3 | .32 |

| Neurological; n (%) | ||||

| Seizures | 1 (7.1) | 11 (10.1) | 0.79; 0.09–6.7 | .83 |

| Psychosis | 2 (14.2) | 10 (9.2) | 1.9; 0.36–10.11 | .44 |

| Hematology; n (%) | ||||

| Leukopenia | 8 (57.1) | 49 (45.3) | 1.38; 0.44–4.29 | .56 |

| Hemolytic anemia | 3 (21.4) | 14 (12.9) | 1.67; 0.41–6.76 | .46 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 20 (18.5) | 0.13; 0.00–2.42 | .17 |

| Vasculitis; n (%) | 4 (28.5) | 13 (12) | 2.86; 0.78–10.46 | .11 |

| Sicca syndrome; n (%) | ||||

| Dry eye | 0 | 15 (16) | 0.20; 0.01–3.5 | .27 |

| Dry mouth | 0 | 4 (4) | 0.77; 0.03–15.2 | .86 |

The SLEDAI score in the population with negative anti-P ribosomal antibodies was, on average 3.93 (SD 4.76) and, in patients with positive anti-P ribosomal antibodies, on average 3.58 (SD 4.12; P=.97).

DiscussionIn our study we analyzed the clinical and laboratory characteristics of SLE patients who presented their disease onset before age 16 (young) and compared them with adult SLE patients. The presence of malar rash, photosensitivity, vasculitis, skin rash and neurological involvement (seizures and psychosis) was more frequent in patients with juvenile SLE. When we compared the profile of autoantibodies between the 2 groups of patients, we found that anti-P ribosomal antibodies were significantly more prevalent in juvenile SLE (27% vs 5.62%). We found no association of anti-P ribosomal antibodies with other autoantibodies. Alopecia and rash (non-discoid) were the only clinical manifestations that were significantly associated with the presence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies.

Most of the studies reported above agree that there is a higher prevalence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies in juvenile SLE; our study confirmed these findings. It is known that certain characteristics of the study population, such as ethnicity, disease status (higher prevalence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies in active SLE) and treatment intensity makes the prevalence of this autoantibody variable and differs between different studies. Reichlin et al.11 reported a prevalence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies in 42% of patients with juvenile SLE where a large percentage of them had active SLE. Hoffmann et al.,7 unlike previous authors, found a prevalence of 25%, and Press et al.31 in a previously published study reported a prevalence of 20%. These last 2 studies showed no detail on the activity of the disease and had a prevalence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies similar to that of our study. There is considerable discrepancy in the literature regarding the association between anti-P ribosomal antibodies and different clinical manifestations in juvenile SLE. Reichlin et al.11 found that anti-P ribosomal antibodies were associated with renal involvement. Quite the opposite was reported by Hoffman et al.,7 who described that the presence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies in the absence of anti-DNA acted as a protector from kidney involvement. In the adult SLE population, other authors found no association between anti-P ribosomal antibodies and the presence of membranous nephropathy.20 Like us, Press et al.31 found no association between this autoantibody and kidney involvement.

The association of anti-P ribosomal antibodies with neurological manifestations in patients with juvenile SLE is also controversial. Aldar et al. observed autoantibody more frequently28 in patients with juvenile SLE and anxiety, but not with more severe clinical manifestations of the central nervous system. Reichlin et al.11 and Hoffman et al.7 do not mention the association between anti-P ribosomal antibodies and neurological compromise. In our study, although we found a higher prevalence of neurological manifestations (psychosis and seizures) in juvenile SLE, we did not find a statistically significant association between the anti-P ribosomal antibodies and such events, either in the analysis of the total patient population studied or in juvenile SLE.

It has been reported the anti-P ribosomal antibodies correlate with disease activity as measured by SLEDAI and with the presence of anti-DNA. In our study no relationship between disease activity measured by SLEDAI and anti-P ribosomal antibodies31 was found.

One of the major limitations of our study is the small number of patients with juvenile SLE due to difficulties in recruitment. The anti-P ribosomal antibodies were measured in a single determination, so we could not have detected their presence in patients who were inactive at the time of sampling. On the other hand, in the sample there are only 14 patients with positive anti-P ribosomal antibodies; this may have limited the possibility of finding statistically significant associations between antibody presence and clinical manifestations.

Despite the limitations, this study confirms the increased prevalence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies in patients with juvenile SLE and found no association of their presence with renal and CNS manifestations. Alopecia and rash (non-discoid) were the only clinical manifestations that were statistically associated with the presence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this research has not performed experiments on humans or animals.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of data from patients and all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Conflict of InterestThe authors have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Pisoni CN, Muñoz SA, Carrizo C, Cosatti M, Álvarez A, Dubinsky D, et al. Estudio multicéntrico de prevalencia de anticuerpos antirribosomal P en lupus eritematoso sistémico de comienzo juvenil comparado con lupus eritematoso sistémico del adulto. Reumatol Clin. 2015;11:73–77.