To assess the percentage of patients who fulfill the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1990 as well as the ACR 2010 classification criteria, to evaluate whether there is a correlation between tender points and the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) as well as signs and symptoms that predict a fibromyalgia (FM) subtype and to identify those which have greater impact on functioning.

Materials and methodsWe performed a cross-sectional comparative study of 206 patients with previous clinical diagnosis of FM. The studied variables were age, sex, years of disease, tender points, control points, WPI, Symptom Severity Score, subtype of FM, presence of other rheumatic disorders and the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) score.

ResultsThe new diagnostic criteria of FM correctly classified 87.03% of patients who satisfied the ACR 1990 criteria. Both criteria were equally effective in assessing the impact of the disease. FM had a severe impact on the quality of life in 74.87% of patients. Somatoform disorder was the predominant subtype. Hyperalgesic FM had a significantly lower FIQ score than the somatoform disorder and depressive subtypes.

ConclusionThe ACR 2010 criteria are a simple evaluation tool to use in the primary care setting, that incorporate both peripheral pain and somatic symptoms. New and old criteria should coexist; they enable a major comprehension and ease the management of this prevalent disease.

Evaluar el grado de concordancia entre los criterios antiguos de fibromialgia (FM) y los criterios del American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 2010, valorar si hay correlación entre puntos y áreas dolorosas, así como los signos y los síntomas que permitan predecir un tipo específico de FM (depresivo, hiperalgésico o somatizador) e identificar aquellos que presenten mayor correlación con la afectación vital de la enfermedad.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio transversal comparativo en el que se incluyó a 206 pacientes con diagnóstico clínico previo de FM. Las variables evaluadas fueron: edad, sexo, años de evolución de la enfermedad, puntos dolorosos, puntos control, áreas dolorosas, presencia de fatiga, alteraciones del sueño y trastornos cognitivos, síntomas somáticos, tipo de FM, presencia de otras enfermedades reumatológicas y la puntuación promedio del cuestionario de impacto de la fibromialgia (FIQ).

ResultadosLos nuevos criterios diagnósticos clasificaron correctamente el 87,03% de los casos que cumplían con la antigua definición. Ningún criterio fue superior al otro para valorar el impacto de la enfermedad. El 74,87% de los pacientes presentó una afectación vital severa. Se evidenció un predominio del tipo de FM somatizador. El tipo hiperalgésico presentó un promedio de FIQ más bajo que los tipos depresivo y somatizador.

ConclusiónLos criterios del ACR 2010 constituyen una manera simple de evaluar pacientes con FM y tienen en cuenta las manifestaciones subjetivas de la enfermedad. Los nuevos criterios deberían convivir con los criterios antiguos; aportan una mayor comprensión y facilitan el manejo de esta patología tan prevalente.

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a syndrome characterized by diffuse, chronic musculoskeletal pain, non-articular in origin, which is evidenced by palpation of tender points in specific anatomic areas and is usually accompanied by unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, morning stiffness and cognitive impairment. Fibromyalgia affects about 0.5%–5% of the population and is characterized by ambiguity in the diagnosis, uncertainty in the understanding of its pathophysiology and the difficulties of physicians to address it globally.1

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) published classification criteria, based on an examination of tender points, requiring specialized evaluation.2 The presence of chronic widespread (more than 3 months), generalized pain (in at least 3 of the 4 body quadrants), with 11 or more of 18 specific tender points was evaluated.

The impression that the FM was exclusively a musculo-skeletal disease was erroneously created. With the passage of time, there appeared a number of objections (practical and philosophical) to the 1990 ACR classification criteria. It first became increasingly evident that the tender point count was a barrier and was rarely performed in primary care, where most cases of FM were diagnosed, and when they did, these were often evaluated incorrectly. Many physicians were unaware of how to perform the examination of tender points, or simply omitted the procedure. Thus, in practice, the diagnosis of FM has been based primarily on the symptoms reported by patients.

Second, although the symptoms of fibromyalgia (fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, cognitive, etc.) were not considered by the ACR 1990, they have lately been recognized as having hierarchical importance. FM, then, is no longer considered a peripheral musculoskeletal disease and there has been a growing recognition of central sensitization of pain as the underlying neurobiological basis, which explains most of the systemic symptoms.

The new FM diagnostic criteria proposed in 2010 consist of a widespread pain index (Widespread Pain Index [WPI]) and a Symptom Severity Score [SS-Score]. According to the literature, this new method correctly classified 88.1% of cases diagnosed by the 1990 ACR criteria and, since it is essentially based on the information provided by patients, requires no physical examination nor requires specialized observer training, and is well suited to the field of Primary Health Care.3

On the other hand, the heterogeneity of the disease implies that not all patients with FM present and evolve in the same way; For these reasons, Giesecke et al. have issued a recommendation to classify FM into 3 groups, those associated with depression, those where there is an important functional or somatoform disorder or do not have psychopathology. This classification enables the homogenization of groups of patients with similar characteristics and potential common therapeutic approaches.4,5

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the degree of agreement between the old criteria for FM and the 2010 ACR criteria.

Secondary objectives were to assess whether there is a correlation between points and painful areas, and signs and symptoms that predict a specific type of FM (depressive, hyperalgesic or somatizing) and, secondly, to identify the signs and symptoms that exhibit a greater correlation with vital disease involvement, the impact of the disease for different types according to each criterion.

Materials and MethodsWe present a cross-sectional comparative study, approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Chiron Dexeus University Hospital of Barcelona, Spain.

The study included patients with a clinical diagnosis of FM, 18 or older, who came successively to the outpatient Rheumatology Clinic of the Valld’Hebron Hospital and the Chiron Dexeus University Hospital in Barcelona between 15 August 2012 and 15 November 2012, and provided informed consent for participation in the study. The data was processed using the SPSS statistical software version 22.

The variables evaluated were: age, gender, years of disease progression, pain points, control points, painful areas, presence of fatigue, sleep disturbances and cognitive disorders, somatic symptoms, type of FM (hyperalgesic, depressed or somatizer, according to the classification of Giesecke et al.,5,6 reference institution, concomitant presence of other rheumatic diseases, and the average score of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire [FIQ].7

At the start of the visit, the interrogation was conducted4 and then forms were completed to evaluate new criteria for FM. The patient then proceeded to the physical examination of tender points and then 3 control points (back of the thumb, middle third of the forearm and forehead)8,9 were evaluated. Finally, the patients were given questionnaires to assess the impact of disease and psychological disorders.

The WPI comprises 19 areas of the body and the patient should show where he or she had pain in the past week. WPI scoring one point for each painful area (score 0–19) was calculated. The SS-Score was determined considering the following symptoms: fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, cognitive manifestations and somatic symptoms. Each symptom is assigned a 0 to 3 score, according to its severity (in the case of the first 3) or the amount (in case of somatic symptoms).

It was considered that a patient met the diagnostic criteria for FM if a WPI score ≥7 and an SS-Score ≥5 or WPI 3–6, SS-Score ≥9 was present.

The pain visual analog scale was used to assess the type of FM, as were the 28-item GoldbergGeneral Health Questionnaire28, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, the catastrophic pain score and the Short Form (SF-36) on health status.10 Thus, the presence of depression, anxiety, catastrophizing, hyperalgesia, pain sensitivity and perceived control over it was assessed.

The statistical methods used for data analysis consisted of the Cohen's f association or agreement index, the Pearson correlation coefficient, Student's t hypothesis test to prove its significance and the analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a F hypothesis test of Snedecor, the test for multiple comparisons (t test) and confidence intervals.

ResultsThe study included 206 patients; 130 were seen at the Rheumatology Department of the Valld’Hebron Hospital and 76 at the Chiron Dexeus University Hospital in Barcelona (Spain). The mean age ± SD of the patients was 53.71±9.48 years. The youngest patient was 30 years and the oldest 82 (Table 1). 95.1% of FM patients analyzed were female. The mean time since disease onset was approximately 8±5.84 years. At the time of the visit, 89.8% of patients met the previous criteria for the diagnosis of FM. 90.29% of patients with FM had no history of another rheumatic disease, while in 20 patients (9.71%) FM was associated with various systemic rheumatic diseases. For various reasons (data loss, refusal to perform the tests), 41 patients (19.9%) could not be classified according to the type of FM. Of the remaining 165, 68.5% (113) belonged to the somatizing type, 20.60% (34) were depressed and only 10.9% (18) had no associated psychopathology. The mean FIQ score was 68.86±18.60 points. Of the 199 patients who answered the questionnaire, 7.54% had scores <39. This means that the disease did not cause interference with the activities of daily living. 17.59% had a moderate vital condition. The remaining patients (74.87%) had a FIQ>59, resulting in a marked disease interference with activities of daily living.

General Characteristics of the Population.

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean±SD | 53.71±9.48 |

| Female, n (%) | 196 (95.1) |

| Years of disease progression, mean±SD | 8.04±5.84 |

| Positive Old Criteria, n (%) | 185 (89.8) |

| Types of fibromyalgia (%)4 | |

| Somatizing | 113 (68.5) |

| Depressive | 34 (20.6) |

| hyperalgesic | 18 (10.9) |

| FIQ, socre, mean±SD | 68.86±18.6 |

SD: standard deviation; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire.

At the time of evaluation, 89.8% of the sample met the 1990 ACR criteria for FM and 84.5% met the ACR 2010 criteria. 78.15% of patients met the requirements of both classifications.

New diagnostic criteria correctly classified 87.03% of the cases that met the old definition. On the other hand, 92.53% of patients who met the ACR 2010 criteria also met the old criteria (Table 2).

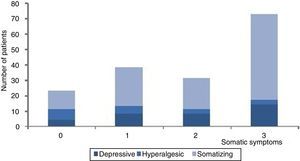

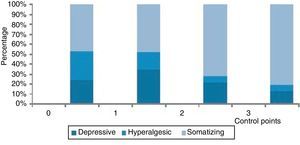

Regarding the control points, 83% of patients had at least one positive on physical examination. There was no association between the presence of these control points or somatic symptoms with the somatizing FM type. These variables behaved independently (Cohen index f=0.26 and 0.24, respectively) (Figs. 1 and 2).

There was a significant moderate positive linear relationship (r=0.540) between the painful points and areas. There was also a statistically significant positive linear association, of weak intensity between tender points, painful areas, somatic symptoms and the symptom severity index with the FIQ (Table 3).

Associations and Correlations Between Variables.

| Variables analyzed | Pearson correlation coefficient (r) | Significance (P) |

|---|---|---|

| Painful Points/painful areas | 0.540 | <.001 |

| Painful Points/FIQ | 0.427 | <.001 |

| Painful Areas/FIQ | 0.462 | <.001 |

| Somatic Symptoms/FIQ | 0.477 | <.001 |

| Sleep, fatigue, cognitive disorders/FIQ | 0.447 | <.001 |

FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire.

The mean FIQ of patients who met the former criteria for FM was greater than those who did not comply with them (71.43±15.78 vs 44.53±25.26). This difference was highly significant (P<.001). Patients who met the new criteria for FM also had a mean FIQ significantly higher than those who did not (71.94±16.41 vs 51.53±20.86).

However, there were no significant FIQ differences between patients who fulfilled 1990 and 2010 ACR criteria, nor among those who did not meet any of the two criteria (Table 4).

Difference in FIQ According to 1990 and 2010 ACR Criteria for FM.

| Criteria | Mean±SD of FIQ | No. | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old | |||

| No | 44.53±25.26 | 19 | <.001 |

| Yes | 71.43±15.78 | 180 | |

| New | |||

| No | 51.53±20.86 | 30 | <.001 |

| Yes | 71.94±16.41 | 169 | |

| Total | 68.86±18.60 | 199 | |

SD: standard deviation; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; FM: fibromyalgia; n: sample.

The average FIQ was significantly lower (P=.01) in patients who had the hyperalgesic FM type (51.8±23.29) than in the depressive and somatizer types (75.34±13.62 and 73.96±14.52, respectively). Between these two subgroups there were no significant differences (P=.898) (Table 5).

Average FIQ Depending on FM Type.

| Type of FM | n | Mean FIQ±SD | 95% Confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Depressive | 32 | 75.34±13.62 | 70.43 | 80.25 | P<.001 |

| Hyperalgesic | 18 | 51.83±23.29 | 40.25 | 63.42 | |

| Somatizing | 112 | 73.96±14.52 | 71.25 | 76.68 | P<.001 |

| Total | 162 | ||||

SD: standard deviation; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; FM: fibromyalgia; n: sample.

In our study, the demographic characteristics of the sample did not differ from the large published series.4,11

The largest subgroup of patients belonged to the somatizing type, which has been identified as having the worst prognosis for presenting high levels of anxiety, depression, catastrophizing and hyperalgesia, and a low control over pain; in other studies, the predominant type was depressive FM, which represents about half of the cases 5.

Most patients who met the criteriaACR 2010 for FM also meet the old criteria for FM in a manner similar to that published by Wolfe et al.,3 where it was observed that up to 14% of patients diagnosed with FM using the 1990 ACR criteria did not meet the new criteria.

When analyzing the tender points, a moderate positive correlation between these and the painful areas reported by patients was evident; in the study of Wolfe et al., these variables showed a strong association 2.

The control points have been proposed as markers of allodynia or hyperalgesia. In our sample, when analyzed along with somatic symptoms, they showed no significant correlation with the somatizing FM type. It was not possible to predict this type of FM without the specific tests to correctly subclassify the disease.

The control points, even when considered a marker for a group of patients with the lowest threshold for pain, do not imply more severe symptoms or more marked functional impact.

The FIQ score pointed to a prevalence of patients with severe life impact, similar to the results reported by Schaefer et al.12

Patients who met either the 1990 or 2010 ACR criteria for FM, had a larger than impact on activities of daily living than those who do not meet them; On the other hand, no method was superior to the other in assessing the impact of disease. A significantly lower than average FIQ was seen in patients with FM compared to those in hyperalgesic type that in the depressive or somatizing type.

All variables taken into account to define new and old criteria for FM showed a weak positive correlation with the FIQ; both pain and somatic symptoms, restless sleep, fatigue and cognitive impairment, contributed similarly to the vital involvement of the disease.

All patients included in the study had a previously established diagnosis of FM. The percentage who did not meet criteria was probably due to symptomatic improvement. As the study was conducted in two reference centers, most of the patients included had several years of treatment; this may have resulted in only those who maintained active symptomatology were being followed, which would explain the large number of patients with somatoform syndrome and severe functional life impact.

FM is the second or third most common diagnosis in the rheumatology practice and is estimated to represent 10%–15% of visits in primary health care.13

The demonstration of objective changes in the field of neurophysiology has provided medical evidence to recognize this disease that occurs only with subjective changes and lacks objective findings. Altered pain processing has been demonstrated at various levels in the nervous system and FM is now considered a neurobiological disease. The pathophysiological mechanism is mainly based on central sensitization, along with genetic and endocrine factors, sleep deprivation, psychosocial stress and physical trauma.

Although in recent years progress has been made in the understanding of this condition, we still lack an objective clinical test to confirm a diagnosis or assess response to treatment. However, this is no different from other, better-known diseases, for example, irritable bowel syndrome, migraine and depression. Despite the existence of a scientific base that has demonstrated organic changes, skepticism still exists on the validity of subjective symptoms and FM remains a huge challenge for the clinician, who must integrate the neurobiological field with the psychosocial one.

The application of the new criteria in primary care has not been assessed in prospective studies; its use is discussed, as it dispenses with the physical examination and ignores any additional study. Although the diagnosis of FM is based mainly on accepted clinical practice largely subjective parameters, the use of the new criteria, which are based solely on the symptoms provided by the patient, carries the risk of missing significant findings of the clinical examination that may guide to alternative diagnoses.

Furthermore, new diagnostic criteria are a simple tool for use in primary care, correctly classifying the majority of cases and, through the SS-Score, assessing the severity and outcome of patients. According to this new concept of FM, symptoms are interpreted not as an all or nothing phenomenon, but with varying severity and intensity fluctuations.14 In this sense, according to Fitzcharles et al, the new criteria are superior to the ACR 1990, as the latter are not useful for monitoring patients chronologically; the loss of a point or painful area for any reason, including symptomatic improvement, may cause some criteria to be erroneously unmet.

In the study by Wolfe et al., the 2010 ACR criteria were easy to apply and a simple way to assess the general health status in patients with FM. They can find a concomitant depression and detect FM in patients with other diseases.15,16 Anyway, so that comparative studies are carried out, it is convenient to use both diagnostic criteria without omitting physical examination. Also, to evaluate their applicability outside the field of the rheumatology clinic, their implementation would be useful in a multicentre study in the field of Primary Health Care.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted only in 2 Rheumatology Units in one city. Second, all patients had a previous diagnosis of FM and most had many years of evolution of the disease, making it impossible to compare the application of both criteria for classification in patients without diagnosis. It was also performed in a short period of time and the number of patients studied was low. Also, for various reasons, almost 20% of patients did not complete the questionnaires in order to be classified according to the threshold of pain and psychological factors.

Since FM is a multifactorial disease, it must be understood from the perspective of a biopsychosocial model, rather than a limited biomedical approach. The new criteria, translated into Spanish, have a sensitivity and specificity similar to the ACR 1990 criteria, and must live alongside the old criteria; they are accessible as a useful tool in the field of Primary Health Care; their ease of application makes them a valuable tool, which provides a greater understanding and facilitates the management of this prevalent condition. Only time and the acceptance of the rheumatology community will tell if the new criteria for FM are here to stay.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare this research did not perform experiments on humans or animals.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of data from patients and all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Conflict of InterestNo financial, work-related or personal conflict of interest was disclosed.

Our sincere thanks to the patients who agreed to participate in this study.

Please cite this article as: Moyano S, Kilstein JG, Alegre de Miguel C. Nuevos criterios diagnósticos de fibromialgia: ¿vinieron para quedarse? Reumatol Clin. 2015;11:210–214.