To determine the perceptions, attitudes and experiences among family caregivers of patients with musculoskeletal diseases (MSD).

MethodsIt is a descriptive, exploratory, qualitative study. Two discussion groups were organized with family caregivers of MSD patients, representing the caregiver profile: gender (men/women) and age (31–45 years/46–65 years); and patient profiles: MSD type (rheumatoid arthritis/ankylosing spondylitis), work status (yes or no for the variables housewife, at least 3 episodes of sick leave, patients who abandoned their work, and patients with permanent work disability). A content analysis based on the Grounded Theory was done to detect and explore emerging categories.

ResultsThe emerging dimensions were: alterations in daily life activities, need for caregiver support, physical and psychological impact on the caregiver, characteristics of the patient, and several aspects of care. Relevant experiences mentioned were: the diagnosis of a MSD changes the patient and their family members’ life affecting work, financial, social, psychological and physical spheres, making it necessary help for basic activities of daily living. Early age at onset or severe MSDs require dedication and effort on the part of caregivers which increases with time. This leads to a great emotional overload on the caregivers, which may be modulated by the support they receive when providing care.

ConclusionThe primary consequences for caregivers are loss of purchasing power, work problems, social isolation and emotional stress. Programs for effective at-home support need to be developed with streamlined administrative processes to quickly classify the level of disability and provide official assistance.

Conocer las percepciones, las actitudes y las vivencias de los familiares que cuidan a los pacientes con enfermedades músculo-esqueléticas (EME).

MétodosEstudio cualitativo, descriptivo y exploratorio. Se realizaron 2 grupos de discusión con cuidadores seleccionados mediante las variables: sexo, edad del cuidador (de 31 a 45 años/de 46 a 65 años), diagnóstico (artritis reumatoide/espondilitis anquilosante) y situación laboral del paciente (amas de casa/pacientes con al menos 3 episodios de baja laboral/pacientes que abandonaron su trabajo/pacientes con incapacidad declarada). Se hizo un análisis de contenido basado en la Grounded Theory para detectar las categorías emergentes.

ResultadosLas dimensiones emergentes fueron: alteraciones en la vida cotidiana, necesidad de apoyo del cuidador, repercusiones físicas y psicológicas sobre el cuidador, características del paciente y descripción de los cuidados. Entre las vivencias destaca que el diagnóstico de una EME altera la vida del paciente y los familiares, repercute en la esfera laboral, económica, social, psicológica y física llegando a necesitar ayuda para las actividades básicas de la vida diaria. Las EME diagnosticadas a edades tempranas o muy incapacitantes, exigen dedicación y esfuerzo en los cuidados que aumentan con el tiempo. Esto produce una gran sobrecarga emocional en el familiar, modulada por el apoyo recibido para cuidar.

ConclusiónLas principales consecuencias detectadas para los cuidadores son pérdida de poder adquisitivo, problemas laborales, aislamiento social y su sobrecarga emocional. Se precisa desarrollar programas de apoyo domiciliario eficaces, con trámites oficiales ágiles para poder clasificar rápidamente el grado de discapacidad y así poder tramitar ayudas oficiales.

Musculoskeletal diseases (MD) are highly prevalent and tend to be chronic, causing disability and great social, labor, economic and quality of life burden to patients and their family environment1,2 MD seriously affect the ability to develop work and activities of daily living. Only rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in Spain in 2004 caused the loss of over 42,000 adjusted life years due to disability (Disability Adjusted Life Years [DALYs]), representing 0.89% of total DALYs lost.3

The disability caused by MD is the reason some patients need a caregiver. Caregivers can be formal (paid) or informal. Informal care is known as providing support for dependents by people, mostly family (over 80% of cases), friends, neighbors or others who do not receive any financial reward for the help they provide.4,5 The profile of the informal caregiver (IC) more often corresponds to a woman about 50–60 years, first-degree relative, housewife, and with primary education.6–9 Caring for a family member can have a significant impact on health and quality of life of caregivers, leading to anxiety, irritability, insomnia, fatigue, decreased leisure time and changes in their social and economic situation.5,10–12 These situations can generate physical and psychological overload “and significant labor, social and personal losses in caregivers’.13,14

Despite the impact of MD on caregivers, is largely unknown how the IC manage, perceive and live the fact of caring for a relative with MD. For these reasons, we designed this study with the objective of knowing the perceptions, attitudes and experiences of relatives of patients with MD who they look after.

Materials and MethodsThe study design was qualitative research, developed with 2 discussions groups (DG) to explore the perceptions, attitudes and experiences of family members caring for a patient with MD for more than one year.

The inclusion criterion for the relative or IC was caring after the patients for more than a year and that the patient have a diagnosis of RA or ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The composition of the DG was segmented by caregiver variables (gender and age: 31–45 years, or 46–65 years), and the patient diagnosis (RA or SA) and employment status (housewife, at least 3 episodes of sick leave, having stopped working and having a declared disability).

The family selection was made after identifying patients with RA or SA contacting 3 Rheumatology departments in Madrid (Hospital La Paz, Hospital La Princesa, and Hospital 12 de Octubre), and 3 patient associations: National Arthritis Coordinator (CONARTRITIS), Madrid Association of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis (AMAPAR) and Sick Associated Parleños with Spondylitis and Arthritis (EDEPA). Each of the family members was informed of the purpose of the meeting, of the fact that the study results could improve support programs for caregivers that group discussion were anonymous but would be recorded on a voice recorder to transcribe the speech and then analyze it in writing that there would be no data enabling researchers to identify any participant that the decision to participate was voluntary and that participation would have no impact on the health care of the sick relative. All family members verbally agreed to participate.

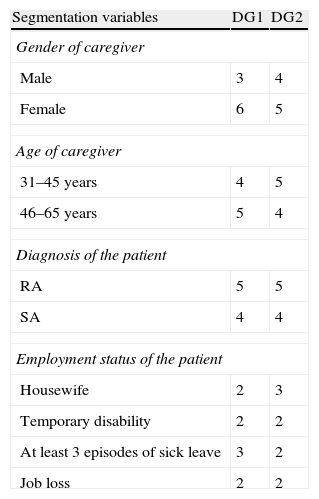

Relatives were included consecutively to provide the number and profile of the IC needed. Each GD attended 9 persons, whose composition is shown in Table 1. The DG met in July 2009, on different days, with sessions lasting approximately an hour and a half for each group.

Profile of Informal Caregivers Attending Discussion Groups.

| Segmentation variables | DG1 | DG2 |

| Gender of caregiver | ||

| Male | 3 | 4 |

| Female | 6 | 5 |

| Age of caregiver | ||

| 31–45 years | 4 | 5 |

| 46–65 years | 5 | 4 |

| Diagnosis of the patient | ||

| RA | 5 | 5 |

| SA | 4 | 4 |

| Employment status of the patient | ||

| Housewife | 2 | 3 |

| Temporary disability | 2 | 2 |

| At least 3 episodes of sick leave | 3 | 2 |

| Job loss | 2 | 2 |

DG, discussion group; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SA, ankylosing spondylitis.

Before the meeting of the DG, a discussion map was elaborated with the following topics included: personal changes of patients and caregivers (daily life, mood disturbances, patient's lost opportunities, employment consequences, economic impact or loss of purchasing power) and changes in the family (daily life, family overload, need to care for the family member who has RA or AS and undertaking tasks previously performed by the affected family member, loss of opportunities for family members and loss of purchasing power).These aspects of the discussion map were only enunciated by the moderator if they spontaneously emerged among group members.

The DG session was recorded and transcribed verbatim. The analysis of the transcripts was performed with the Nvivo 7.0 software and coded to detect emerging dimensions. Subsequently, an analysis of notoriety was done taking into account the number of times the dimensions appeared in the text. After coding, we conducted a descriptive content analysis based on Grounded Theory.15 Finally, participants were classified by the variables gender, shared care, availability of formal caregivers (FC) and employment status of the IC in order to know the relevance to address issues such as emotional overload, altered mood and guilt feelings.

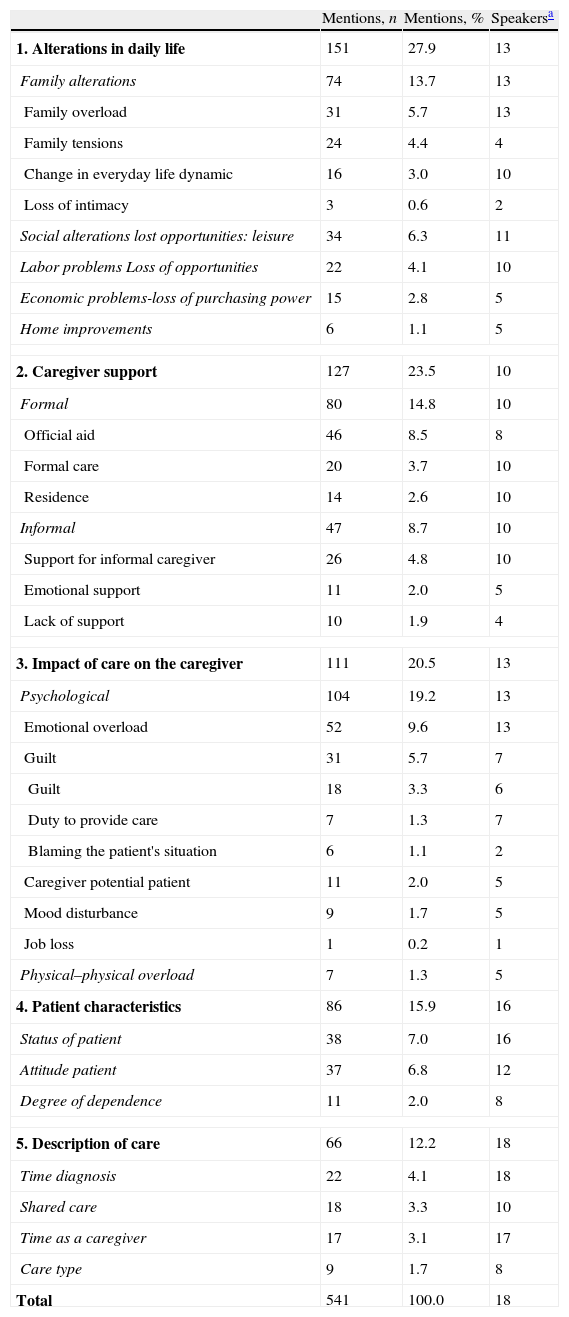

ResultsThe most noticeable topics after coding are shown in Table 2. The most frequently mentioned items are those related to family dynamic disturbances, followed by caregiver support, and the impact of care on the caregiver. Patient characteristics and description of care are less frequently mentioned.

Mentions of Emerging Issues in the Discourse of the Discussion Groups.

| Mentions, n | Mentions, % | Speakersa | |

| 1. Alterations in daily life | 151 | 27.9 | 13 |

| Family alterations | 74 | 13.7 | 13 |

| Family overload | 31 | 5.7 | 13 |

| Family tensions | 24 | 4.4 | 4 |

| Change in everyday life dynamic | 16 | 3.0 | 10 |

| Loss of intimacy | 3 | 0.6 | 2 |

| Social alterations lost opportunities: leisure | 34 | 6.3 | 11 |

| Labor problems Loss of opportunities | 22 | 4.1 | 10 |

| Economic problems-loss of purchasing power | 15 | 2.8 | 5 |

| Home improvements | 6 | 1.1 | 5 |

| 2. Caregiver support | 127 | 23.5 | 10 |

| Formal | 80 | 14.8 | 10 |

| Official aid | 46 | 8.5 | 8 |

| Formal care | 20 | 3.7 | 10 |

| Residence | 14 | 2.6 | 10 |

| Informal | 47 | 8.7 | 10 |

| Support for informal caregiver | 26 | 4.8 | 10 |

| Emotional support | 11 | 2.0 | 5 |

| Lack of support | 10 | 1.9 | 4 |

| 3. Impact of care on the caregiver | 111 | 20.5 | 13 |

| Psychological | 104 | 19.2 | 13 |

| Emotional overload | 52 | 9.6 | 13 |

| Guilt | 31 | 5.7 | 7 |

| Guilt | 18 | 3.3 | 6 |

| Duty to provide care | 7 | 1.3 | 7 |

| Blaming the patient's situation | 6 | 1.1 | 2 |

| Caregiver potential patient | 11 | 2.0 | 5 |

| Mood disturbance | 9 | 1.7 | 5 |

| Job loss | 1 | 0.2 | 1 |

| Physical–physical overload | 7 | 1.3 | 5 |

| 4. Patient characteristics | 86 | 15.9 | 16 |

| Status of patient | 38 | 7.0 | 16 |

| Attitude patient | 37 | 6.8 | 12 |

| Degree of dependence | 11 | 2.0 | 8 |

| 5. Description of care | 66 | 12.2 | 18 |

| Time diagnosis | 22 | 4.1 | 18 |

| Shared care | 18 | 3.3 | 10 |

| Time as a caregiver | 17 | 3.1 | 17 |

| Care type | 9 | 1.7 | 8 |

| Total | 541 | 100.0 | 18 |

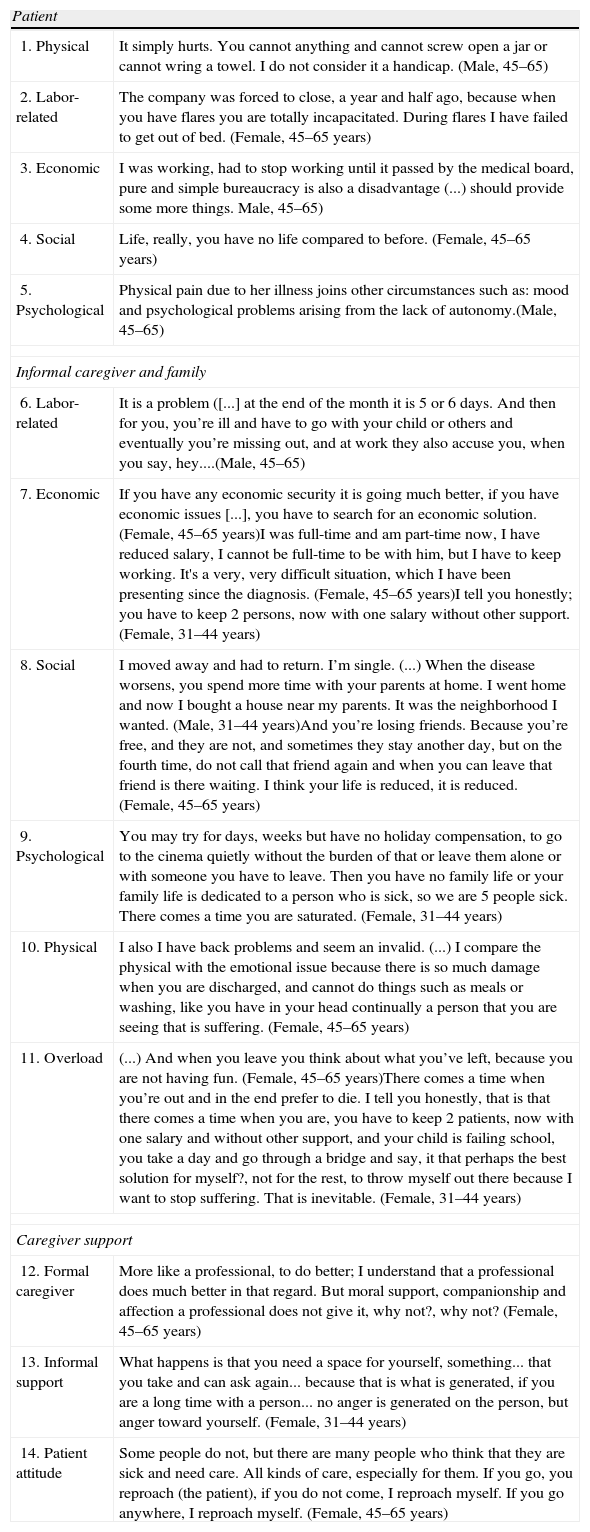

The content analysis allows the description of how the family absorbs patient care, whether it is a family in which a caregiver exclusively assumes all care, or families in which the load is shared between the members of one or more households (generally, children of patients, with their families). The IC argues that the diagnosis of MD is life changing, causing a shift in the patient's, the IC and the family's daily life. The change of life of the patients is motivated by pain and mobility problems that force them to reduce or abandon daily activities, which in turn must be assumed by other people. Caregivers perceive how this affects the patient, their IC and their family, in the physical, labor, economic, social and psychological spheres of life. As an illustration of this analysis, transcripts are shown verbatim in Table 3.

Verbatim Examples of the Impact of the Diagnosis of RA or SA on the Patient, Family or Informal Caregivers and Caregiver Support.

| Patient | |

| 1. Physical | It simply hurts. You cannot anything and cannot screw open a jar or cannot wring a towel. I do not consider it a handicap. (Male, 45–65) |

| 2. Labor-related | The company was forced to close, a year and half ago, because when you have flares you are totally incapacitated. During flares I have failed to get out of bed. (Female, 45–65 years) |

| 3. Economic | I was working, had to stop working until it passed by the medical board, pure and simple bureaucracy is also a disadvantage (...) should provide some more things. Male, 45–65) |

| 4. Social | Life, really, you have no life compared to before. (Female, 45–65 years) |

| 5. Psychological | Physical pain due to her illness joins other circumstances such as: mood and psychological problems arising from the lack of autonomy.(Male, 45–65) |

| Informal caregiver and family | |

| 6. Labor-related | It is a problem ([...] at the end of the month it is 5 or 6 days. And then for you, you’re ill and have to go with your child or others and eventually you’re missing out, and at work they also accuse you, when you say, hey....(Male, 45–65) |

| 7. Economic | If you have any economic security it is going much better, if you have economic issues [...], you have to search for an economic solution. (Female, 45–65 years)I was full-time and am part-time now, I have reduced salary, I cannot be full-time to be with him, but I have to keep working. It's a very, very difficult situation, which I have been presenting since the diagnosis. (Female, 45–65 years)I tell you honestly; you have to keep 2 persons, now with one salary without other support. (Female, 31–44 years) |

| 8. Social | I moved away and had to return. I’m single. (...) When the disease worsens, you spend more time with your parents at home. I went home and now I bought a house near my parents. It was the neighborhood I wanted. (Male, 31–44 years)And you’re losing friends. Because you’re free, and they are not, and sometimes they stay another day, but on the fourth time, do not call that friend again and when you can leave that friend is there waiting. I think your life is reduced, it is reduced. (Female, 45–65 years) |

| 9. Psychological | You may try for days, weeks but have no holiday compensation, to go to the cinema quietly without the burden of that or leave them alone or with someone you have to leave. Then you have no family life or your family life is dedicated to a person who is sick, so we are 5 people sick. There comes a time you are saturated. (Female, 31–44 years) |

| 10. Physical | I also I have back problems and seem an invalid. (...) I compare the physical with the emotional issue because there is so much damage when you are discharged, and cannot do things such as meals or washing, like you have in your head continually a person that you are seeing that is suffering. (Female, 45–65 years) |

| 11. Overload | (...) And when you leave you think about what you’ve left, because you are not having fun. (Female, 45–65 years)There comes a time when you’re out and in the end prefer to die. I tell you honestly, that is that there comes a time when you are, you have to keep 2 patients, now with one salary and without other support, and your child is failing school, you take a day and go through a bridge and say, it that perhaps the best solution for myself?, not for the rest, to throw myself out there because I want to stop suffering. That is inevitable. (Female, 31–44 years) |

| Caregiver support | |

| 12. Formal caregiver | More like a professional, to do better; I understand that a professional does much better in that regard. But moral support, companionship and affection a professional does not give it, why not?, why not? (Female, 45–65 years) |

| 13. Informal support | What happens is that you need a space for yourself, something... that you take and can ask again... because that is what is generated, if you are a long time with a person... no anger is generated on the person, but anger toward yourself. (Female, 31–44 years) |

| 14. Patient attitude | Some people do not, but there are many people who think that they are sick and need care. All kinds of care, especially for them. If you go, you reproach (the patient), if you do not come, I reproach myself. If you go anywhere, I reproach myself. (Female, 45–65 years) |

As reflected, the physical impact of the patient with advanced-stage MD or during flares leads to an important degree of dependence, which even requires help to perform ADL (Table 3, verbatim 1). Relatives state that, in the workplace, patients may end up abandoning their occupation, even before retiring age or due to disability. Some patients have presented disabling processes so long that they feel unable to work due to their degree of disability (Table 3, verbatim 2). They emphasize that their purchasing power is reduced due to recurrent sick leave, reduced working hours or job loss (Table 3, verbatim 3). Socially, due to loss of mobility, pain and disability, family members describe how the patients perceived changes in their life (Table 3, verbatim 4), with a tendency to isolation and emotional apathy (Table 3, verbatim 5).

Patients with advanced stages MD are chronic and usually have been diagnosed at relatively early ages, and their care requirements must be maintained for a long time. Recursively, relatives express how patients may require assistance in their ADLs that require considerable time, effort and dedication. The IC, in addition to assuming their care, must carry out activities previously performed the patient, without abandoning the obligations of everyday life. Taking care of the patients’ daily life alters both caregivers and families. The family routine seems to be just rotating around the patient, and the former must reconcile patient care with work and family social life.

One of the first problems are labor issues arising from the burden of care, for example, absenteeism caused by the constant request for permission to meet care needs, accompanying the patient to consultations and medical tests, and when their dependency increases due to the progression of the disease, in flares or in crisis come that require care for ADL. Some even stated that the caring for the patient force the individual to reduce the time devoted to family, with consequent loss of purchasing power (Table 3, verbatim 6). Some believe that the loss of purchasing power was caused by the decrease in revenue due to the possible reduction of the IC-time, patient and/or IC abandonment of work or limitations to advance in the workplace. Some also point out that spending increases due to care because, among other reasons, of the possible need for a caretaker, either permanent or ad hoc, for possible home improvements, or the need for special resources for the care of family and drug spending and/or due to an added member in their home, when the family member moves in with his IC (Table 3, verbatim 7).

According to relatives, social changes come when free and family time decreases (Table 3, verbatim 8). The isolation and loss of social network of the IC appear, because there is no free time, accentuating the emotional overload, together with other psychological effects, such as the familiar feeling of abandonment when left in the care of someone else to try to obtain relief. Leisure and family relationships also suffer because the patient's mobility limits and conditions plans. Constants are disclaimers and the impediments to enjoy leisure time that can generate in the IC a feeling of rejection toward their family (Table 3, verbatim 9).

The physical impact on the IC barely mentioned, focusing on the psychological consequences which are much more relevant to them (Table 3, verbatim 10). In general, there is a high emotional overload, with altered mood and guilt (Table 3, verbatim 11). These feelings are caused by the burden of care, the feeling of dependency of the patient and the excessive empathy with the suffering of the MD by the family, sometimes forget themselves. The IC report that the overload feeling arises when the IC and their families perceive that they do not have enough time for themselves, when relative asks for more help than needed or are becoming more dependent. One of the main indicators of overload is underlying guilt when the IC feel that, despite all the care provided, more and better care for the family member with RA or AS could still be provided. This feeling turns to the IC in the care of his family, reinforced by a sense of duty to provide care. Guilt feeds the providers attitude to some patients. Far from comforting the caregiver, they feel that their care is not sufficient and underlines their sense of futility. The IC emotional overload is marked by expressing feelings of sadness, bitterness and depression. The IC are very susceptible and easily irritated. They admit guilt just by turning against the patient, when the IC is abused, setting blame on the patients for their situation.

They recognize that one way to ease the burden of family care of AR or SA is receiving support through CF (Table 3, verbatim 12), through official or self-funded support by the family. The IC who have CF are easier to reconcile with family, work and social life and reducing tensions. The IC believe that formal caretakers are scarce and insufficient and do not solve their problems. The bureaucracy is often tedious. They claim aid is nonexistent in practice for home help as well as for psychological support for both the patient and the IC. In addition to formal support, the IC requested support from family and close friends who they also deemed insufficient (Table 3, verbatim 13). Having informal support means having time to devote to oneself, reduces the burden and leads to improved care, while the lack of support causes isolation. The lack of time to take a break generates more emotional overload and increases the demand for psychological support. The emotional overload of the IC leads to patients presenting mental disorders such as depression or anxiety. The IC mention having sought help from their family doctors, mainly receiving pharmacological solutions, while they demand emotional support to rebuild their social life and break out of isolation.

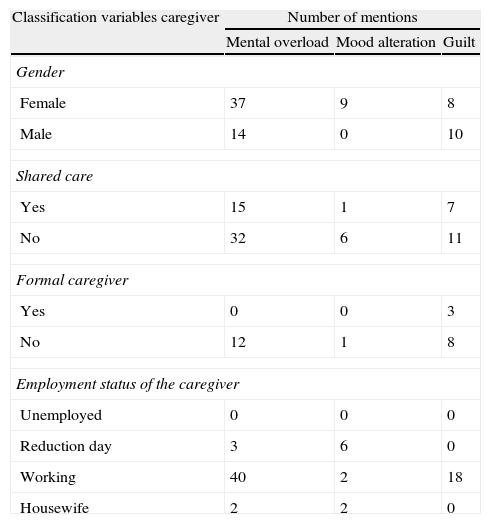

After analyzing the classification of the 3 major psychological impact items, overloading, altered mood and guilt, we see how the IC that are exclusively cared for by their family, lack of CF and are working, are the ones where this alterations are more common (Table 4).

Classification of Item Mentions by the Groups Regarding Mental Overload, Altered Mood and Guilt by Gender, Shared Care, Formal Caregiver and Caregiver Employment Status.

| Classification variables caregiver | Number of mentions | ||

| Mental overload | Mood alteration | Guilt | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 37 | 9 | 8 |

| Male | 14 | 0 | 10 |

| Shared care | |||

| Yes | 15 | 1 | 7 |

| No | 32 | 6 | 11 |

| Formal caregiver | |||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| No | 12 | 1 | 8 |

| Employment status of the caregiver | |||

| Unemployed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reduction day | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| Working | 40 | 2 | 18 |

| Housewife | 2 | 2 | 0 |

The main findings of the content analysis indicate that the support received by the IC to meet their family members’ care leads to an emotional overload, affecting their relationship with the patient and impacting their daily lives. The results support how the diagnosis of MD alters all areas of the patient's, IC and the family's daily life. The impact for both the patient and the family caregiver increases with an increasing degree of physical dependence, intensity and duration of care required, and less social support and help is received.13

An important factor which can improve the situation of the IC and the family is the supporting care. This aspect is recognized by the 39/2006 Law on the Promotion of Personal Autonomy and Care for dependent people, but despite having become a law, does not extend to all people in need. This IC support could avoid or reduce impact of care, and consequences such as labor problems, reduced income and social isolation, which leads to the emotional overload of the IC.13

Regarding the emotional overload, the economic benefits, and especially the psychological ones, of the IC working outside the home outweigh the disadvantages, improving IC–patient relationship.13 IC's that work need not abandon their job, helping fulfill their dual role and combine productive and family responsibilities. If they cannot reconcile this, options tend to be leaving their job, or being expelled from the labor market, or have limited options for progress in work. Similarly, the IC that does not work is less likely to do so.16

Consistent with this analysis, another study identified the IC main demands as formal aid at home (39%) and economic aid (32%).17 Caring non-stop for a patient worsens overloading, reduces self-esteem and worsens IC-patient relationship.13,14,18 These compensations serve to reduce emotional overload.

If institutionalized formal support is guaranteed, IC–patient relationship improves, increasingly reducing IC guilt for attempting to take a break, diluting the feeling of rejection toward the family and the feeling that “I do not care enough”.3

The IC state they also need emotional support, but instead are mainly given drugs for anxiety or depression, when they would prefer counseling, a fact that is reflected in other studies.13 In addition, their demand for receiving psychological help reduce the burden of care in order to enjoy leisure time, reversing the IC's damaged welfare and improving patient care.

Other research also highlights how the economic factor negatively influences the IC's family and emotional overload.13,18Given the serious lack of institutional support and the high cost patient care, only families with enough purchasing power to ensure formal support are able to reduce the impact of the burden of care on their daily lives. This lack of support is a great social opportunity to reduce labor costs.13,16,17

Invisible costs assume IC directed care, for example, devoting 625 million hours alone to patients with RA17 due to lost social rights (unemployment benefits, contributory pension) for being excluded from the labor market or not having been incorporated, while they were performing a necessary, but not recognized, unpaid job in a welfare state.13,16,17

Among the limitations of this study, those of a qualitative study may be mentioned. The results are not statistically representative, but they are a phenomenological explanation that helps to understand experiences, perceptions and attitudes of caregivers. Another weakness could be due to the non-availability of data on disability of patients, this being important in the impact of the families who participated in the focus groups. However, the distribution of employment status of patients (Table 1) can shed light on their degree of disability. As can be noted, the qualitative findings are consistent with results obtained in other studies in which there is a significant lack of welfare support.

In summary, the caregivers of patients with MD have negative consequences, such as loss of purchasing power, labor problems, social isolation and emotional overload. The results point to the importance of developing programs that minimize the effect of the impact on care of patients with MD who are protected by law dependency. These programs should ensure dignified care for patients with MD during flares, crises or permanently, if required, so that the IC can develop, at least, a job and is not affected by future impacts, such as loss of social rights that lead to poverty or even social exclusion. Development of effective home support programs and streamlined procedures requires officials to quickly classify the degree of disability and process aid.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this research has not been done on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors state that no patient data appear in this article.

FinancingThis study was funded by Abbott, who was not involved in its analysis or in drafting the manuscript.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Alfaro N, Lázaro P, Gabriele G, Garcia-Vicuña R, Jover JÁ, Sevilla J. Percepciones, actitudes y vivencias de los familiares de pacientes con enfermedades músculo-esqueléticas: una aproximación cualitativa. Reumatol Clin. 2013;9:334–339.