To identify priorities among comorbidities in axial spondyloarthritis (AxSpA) and recommend how to follow them from an eminently practical perspective.

MethodsA multidisciplinary group was selected (10 rheumatologists—6 of them experts in AxSpA—, 2 general practitioners, an internist, a cardiologist, a gastroenterologist and a psychologist). In a first discussion meeting, the scope and users were established and a list of comorbidities was voted based on frequency and impact. The panellists had to defend the inclusion of each comorbidity/item in the document with consistent arguments. Four panellists and two methodologists developed systematic reviews on controversial topics. In a second meeting, the results of the reviews and the arguments concerning the items to be included were presented. After the meeting, the final document was drafted.

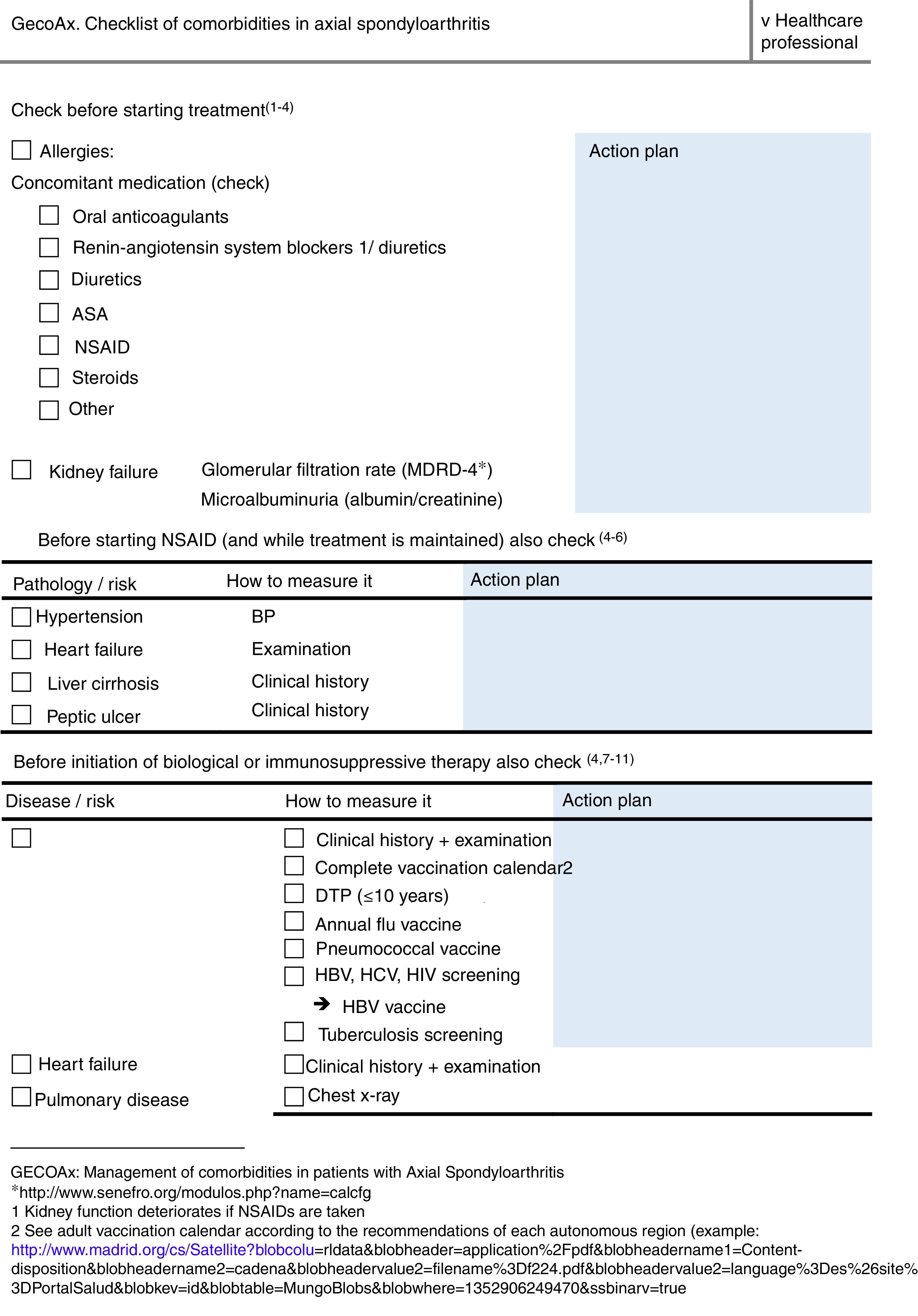

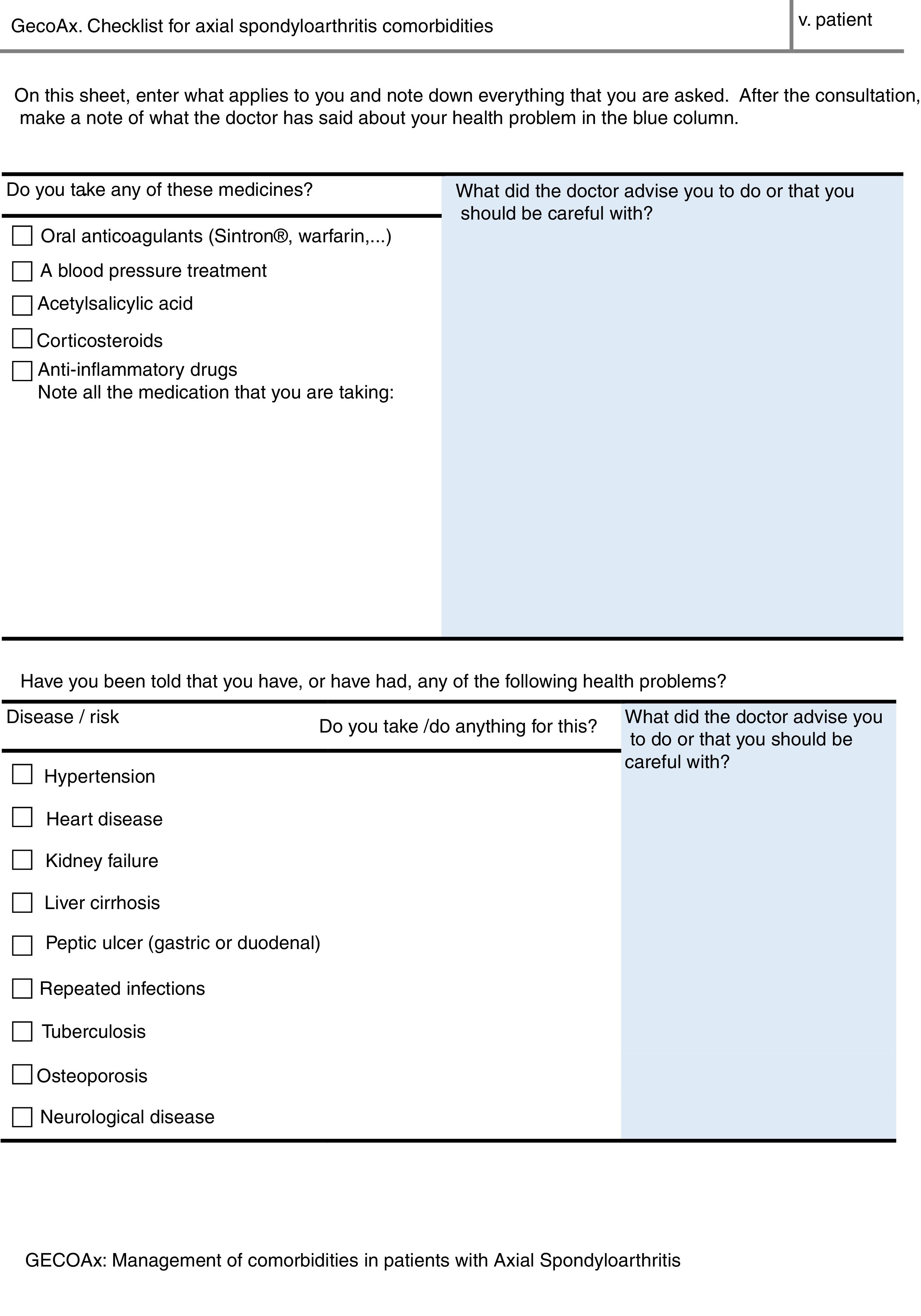

ResultsThe final document includes two checklists, one for health professionals and another for patients; they incorporate cardiovascular risk, renal comorbidities, gastrointestinal risk, lifestyle, risk of infections and vaccinations, pulmonary involvement, concomitant medication, psycho-affective disorders, osteoporosis, and risk of fracture. In addition, the document reflects the arguments favouring the inclusion of each item and how to record the items for subsequent collection. The panel considered it also appropriate to likewise establish «practices to avoid» applicable to comorbidity in AxSpA.

ConclusionsTwo checklists and a list of situations to avoid were generated to facilitate the management of comorbidities in AxSpA. In a future step, their utility and acceptance will be tested by a broad group of users that includes doctors, patients and nurses.

Identificar las comorbilidades prioritarias en la espondiloartritis axial (EspAx) y recomendar cómo hacer su seguimiento desde una perspectiva eminentemente práctica.

MétodosSe seleccionó a un grupo multidisciplinar (10 reumatólogos [6 expertos en EspAx], 2 médicos de familia, una internista, una cardióloga, una gastroenteróloga y una psicóloga). En una primera reunión de discusión, se establecieron el alcance y los usuarios, y se votó una lista de comorbilidades sobre la base de la frecuencia y el impacto. Los panelistas debían defender con argumentos consistentes la inclusión de cada comorbilidad/ítem en el documento. Cuatro panelistas y 2 metodólogos, desarrollaron revisiones sistemáticas en temas controvertidos. En una segunda reunión se presentaron los resultados de las revisiones y los argumentos de todos los ítems a incluir. Tras esta reunión se redactó el documento final.

ResultadosEl documento final incluye 2 listas de comprobación (checklist), una para profesionales sanitarios y otra para pacientes, que recogen: riesgo cardiovascular, comorbilidad renal, riesgo gastrointestinal, estilo de vida, riesgo de infecciones y vacunación, afectación pulmonar, medicación concomitante, trastornos psicoafectivos, osteoporosis y riesgo de fractura. Además, el documento refleja los argumentos para incluir cada ítem y la manera de recoger los ítems. Asimismo, el panel consideró oportuno establecer unas «prácticas a evitar» aplicables a la comorbilidad de la EspAx.

ConclusionesSe generaron 2 listas de comprobación y un listado de escenarios a evitar para facilitar el manejo de las comorbilidades de la EspAx. En pasos posteriores probaremos su utilidad y su aceptación por un grupo amplio de usuarios que incluya médicos, pacientes y enfermeras.

Multimorbidity is the most common form of presentation of chronic disease and has consequences for diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, service use and health outcomes.1

Axial spondyloarthritis (AxSpA) is not considered a rheumatic disease with a major comorbidity load, although it is far from comorbidity-free.2 This could be because it affects young people in the main, and this is precisely why comorbidities most often pass unnoticed and can become a major health problem.

The COMOSPA study cross-sectionally assessed more than 3000 consecutive patients for the prevalence of comorbidities and risk factors in spondyloarthritis patients in 22 countries, and the current gap between the available recommendations and routine clinical practice.3 The diseases that were found most frequently were osteoporosis (13%), gastroduodenal ulcer (11%), cardiovascular events (CV) (4%), solid cancers (3%), and hepatitis B virus infection (HBV) (3%). The most common risk factors for these diseases were arterial hypertension (AHT), smoking, dyslipidaemia, and a family history of CV disease or breast cancer.

The objective of clinical practice guidelines is to promote better quality and equity in healthcare provision, and to serve in decision-making. However, due to factors related to their preparation and implementation, their real impact on care is variable and they are only moderately effective in changing medical practice.4 Since this is not their speciality, the way rheumatologists approach comorbidities can result in inefficiencies and inequities that are based on training and updating of the target disease.

The aim of this paper was to identify priority comorbidities for rheumatologists in the management of patients with AxSpA, make recommendations as to their follow-up, and advise how to practically apply these recommendations, with the ultimate goal of helping rheumatologists assess comorbidities in patients with AxSpA, and ensure less variable management.

MethodsThe coordinator (CG), together with a methodologist (LC), selected a multidisciplinary group based on demonstrated experience and interest in the subject, as well as geographical criteria to ensure representativeness. The panel comprised 10 rheumatologists, an internist, a cardiologist, a gastroenterologist, a psychologist and two family practitioners. They were supported by three methodologists at all times.

At the first discussion meeting, the panel established the scope, users and aspects to be carried through in the recommendations, and the list of comorbidities to be studied and assessed. The panellists had to defend the inclusion or exclusion of each comorbidity/item on the document with consistent arguments. It was also decided, to ensure the maximum practical application, that the final product should be in checklist format, and that it should be extremely straightforward but based on the most solid arguments possible.

Four reviewers, trained and supervised by two methodologists, carried out systematic reviews of observational studies on comorbidities about which there was some controversy. To be specific, the reviews covered the frequency of fractures, osteoporosis and fracture risk factors in AxSpA, the frequency of CV events and the frequency of subclinical CV inflammation. In the first meeting of the group of experts, the questions were prepared using the PICO approach, synonyms were suggested for the search strategy, and the quality measures were chosen. The studies included in the reviews (in preparation as original manuscripts) served to support the items.

A draft of the final document was prepared after the first meeting, with arguments put forward by the panellists, and two checklists were suggested that included the items discussed. These two lists were designed by the methodologists with a view to facilitating data collection, and for checking by the patient and the practitioner. The systematic reviews and checklists were presented at a second meeting, discussed and modified. After the detailed review of the panellists’ contributions, it was also observed that recommendations arose about situations to avoid. Given the practical nature of this document, we decided to add a list of “practices to avoid” to the previous documents. After the second meeting, the items that had no consistent support were removed and the final document was drawn up.

ResultsThe final product of this consensus was the creation of two checklists, one for healthcare professionals (Fig. 1) and the other for patients (Fig. 2). The information in both checklists is complementary. Blank space was left on both sheets for any diagnostic and therapeutic decisions that might be made based on the arguments set out below. The panel suggested that the lists should always be used before starting any new treatment. Outside these situations, frequency of use should be decided based on the structure and features of each individual department and professional environment. In addition to their justification, suggestions are given in each item on how to identify the variables, and clear suggestions on what not to do (all of these are listed in Table 1).

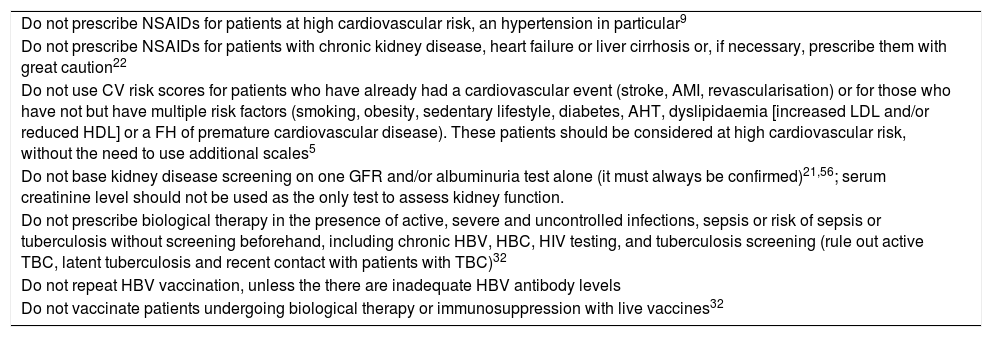

Practices to Avoid in Relation to Axial Spondyloarthritis Comorbidity.

| Do not prescribe NSAIDs for patients at high cardiovascular risk, an hypertension in particular9 |

| Do not prescribe NSAIDs for patients with chronic kidney disease, heart failure or liver cirrhosis or, if necessary, prescribe them with great caution22 |

| Do not use CV risk scores for patients who have already had a cardiovascular event (stroke, AMI, revascularisation) or for those who have not but have multiple risk factors (smoking, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, diabetes, AHT, dyslipidaemia [increased LDL and/or reduced HDL] or a FH of premature cardiovascular disease). These patients should be considered at high cardiovascular risk, without the need to use additional scales5 |

| Do not base kidney disease screening on one GFR and/or albuminuria test alone (it must always be confirmed)21,56; serum creatinine level should not be used as the only test to assess kidney function. |

| Do not prescribe biological therapy in the presence of active, severe and uncontrolled infections, sepsis or risk of sepsis or tuberculosis without screening beforehand, including chronic HBV, HBC, HIV testing, and tuberculosis screening (rule out active TBC, latent tuberculosis and recent contact with patients with TBC)32 |

| Do not repeat HBV vaccination, unless the there are inadequate HBV antibody levels |

| Do not vaccinate patients undergoing biological therapy or immunosuppression with live vaccines32 |

Patients with AxSpA have a poorer CV risk profile than controls; therefore the screening and monitoring of CV risk factors should be included in their general assessment. In Spain, the CARMA study, with a representative sample of 738 patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS), showed a prevalence of CV disease of 7.6%, with an odds ratio compared to healthy controls of 1.77 (95%CI: .96–3.27; P=.07).5 In the COMOSPA study, CV events (myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident) were present or had occurred in 4% of the patients.3 The frequency of CV events was evaluated by systematic review, including 11 estudios,3,6–15 and it was concluded that there might be a mild-to-moderate increased risk of peripheral vascular disease and cerebrovascular disease. There does not seem to be more risk of myocardial infarction than in the general population, and the diagnostic heterogeneity made it impossible to draw an approximate conclusion for other manifestations of ischaemic heart disease. The systematic review to evaluate the frequency of carotid intima-media thickness only yielded 2 publications,16,17 although 21 studies were also found that evaluated the carotid intima-media thickness in patients with spondylitis compared to healthy controls. An increased thickness was observed in 9/21 studies, and no differences were seen in 12. The conclusion of the review (in preparation) is that it is difficult to verify whether patients with AxSpA have increased carotid intima-media thickness.

Consumption of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) can also contribute to an increased CV risk, therefore it is particularly important in these patients, whose CV risk factor, and AHT in particular, should be more strictly monitored.9

The use of SCORE indices has less predictive ability in young people, but relative risk tables can be used (having a particular risk factor compared to not having one) or the “vascular age” estimated.18 In addition, patients who have already suffered a CV event, or those who have not but who have multiple risk factors or a family history of premature CV disease, should be considered at high CV risk, without the need to apply risk scales.18 The risk of a patient who has various risk factors, although not considered serious (e.g. metabolic syndrome) should not be underestimated. If a risk scale is applied (only applicable to patients who have not yet suffered an event), the SCORE index is recommended in Europe.18

Items entered on the checklist: cholesterol, blood pressure, diabetes and smoking.

Total High and Low Density CholesterolTotal, LDL and HDL cholesterol should be measured at least once a year. Subjects at high risk should have an LDL cholesterol less than 70mg/dL18 and should all be under treatment with statins, unless expressly contraindicated. All the patients should have a defined LDL-cholesterol therapeutic objective.19 Although triglycerides should be assessed within the lipid profile, since they are very modifiable by diet and are increased in metabolic syndrome, it is not clear whether they are an independent risk factor.

Blood PressureIt seems useful to measure blood pressure under standard conditions at each visit. The target blood pressure is <140/90mm/Hg.18 If the patient is hypertensive and under treatment with NSAIDs, they should be advised to measure their blood pressure at least once a month9 and if not hypertensive, every 2–3 months.18

DiabetesHbA1c and baseline glycaemia should be measured once a year, unless the patient has gained weight, in which case it should be more often.18 All patients should have a defined target HbA1c level.

SmokingPatients should be asked about their smoking habit at each visit. Smokers should be asked about their intention to quit, and be offered help to do so, referring them to the appropriate clinic (primary care doctor, units providing smoking cessation support, vascular risk units).19

With regard to practices to avoid: (1) NSAIDs should not be prescribed to patients with a high CV risk, and particularly those with AHT9 and (2) it is not necessary to use CV risk scores for patients who have already had a CV event or for those who have not had one but who have multiple risk factors or a family history of premature CV disease; they should be considered at high CV risk without the need to use scales.5

Renal ComorbidityAround 1%–30% of patients with spondylitis have a kidney disorder, according to the various studies, and it usually presents in the form of IgA nephropathy, amyloidosis-related nephropathy or nephropathy caused by drugs such as NSAIDs. Moreover, the condition can be due to poor control of comorbidities that are very common in patients with AS, such as diabetes or ATH.20

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and albuminuria should be assessed at least once a year to screen for chronic kidney disease (CKD) in at-risk populations. Diagnosis should not be based on a single GF or albuminuria determination, and must always be confirmed by several.21

With CKD, monitoring for CV risk factors and progression of the disease should be intensified.21

Items entered on the checklist: glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria.

Glomerular Filtration RateCalculated by MDRD-4 (or MDRD-IDMS).21

AlbuminuriaUsing the albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR): in the first urine sample of the day, the ACR is a more sensitive marker than proteinuria in the context of CKD secondary to diabetes mellitus, AHT or glomerular disease. It is an indicator of vascular damage, identifying subjects at high risk.21

With regard to practices to avoid: (1) NSAIDs should not be prescribed to patients with CV CKD, AHT, heart failure or liver cirrhosis, and if necessary, should be prescribed with great caution22 and (2) screening for kidney disease should not be based on a single GFR determination and/or albuminuria (which should always be confirmed)21; serum creatinine levels should not be used as the only test to assess renal function.

Gastrointestinal RiskThe factors that increase gastrointestinal (GI) risk in patients with AxSpA lie fundamentally in the three areas: taking NSAIDs, the use of methotrexate (MTX) in patients with peripheral disease and the association of AxSpA with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

The risk of GI events in relation to taking NSAIDs is common, and can cause significant morbidity and mortality. This risk is greater in patients with a previous GI history. In a European study, the incidence (95%CI) was 19.0 GI events (17.3–20.8)/100 people-year; uncomplicated events comprised 18.5 (17 to 20)/100 people-year, while the complications were 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1)/100 person-year, the greatest frequency being in the upper digestive tract.23

Prolonged use of MTX can cause liver damage.24

The association between spondylitis and IBD is common; therefore the rheumatologist should look out for warning signs to suspect the condition. Comorbidities were studied in a cohort of 935 AS patients, finding a standardised morbidity ratio for IBD of 9.28 (95% CI, 7.07–11.97).25

To prevent complications as far as is possible in relation to these comorbidities, risk factors should be assessed, the need to avoid alcohol should be stressed, and a healthy weight should be encouraged. It is important that patients treated chronically with MTX receive folic acid supplements (5mg weekly).26

It is important to remember that transaminase levels should be monitored (although for chronic damage this has some limitations; propeptide of collagen III27 could be assessed for these cases or fibroscan monitoring).

Items on the checklist: cirrhosis, changes in bowel habit and health habits.

Liver CirrhosisBearing in mind the possible liver metabolisation of the drugs used in AxSpA, it is necessary to know the patient's liver function grade, and adjust management of the underlying disease to this.23

Changes in Bowel HabitGiven the association of AxSpA and IBD, it is necessary to perform periodic screening for a potential association between both and to monitor symptoms that might relate to IBD.25

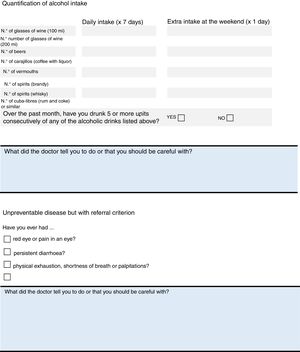

Health Habits (Shared With Other Sections)Smoking (see the CV risk section), alcohol (due to the medication prescribed, and the association with other comorbidities, such as osteoporosis).

LifestyleThe type of work, physical activity, smoking and other socioeconomic factors can affect the progress of AxSpA, and therefore must be taken into consideration.28

Items on the checklist: obesity, smoking, sedentary lifestyle and alcohol.

ObesityThis seems rather more common in patients with AxSpA than in the general population, and is an independent predictive factor in the subjective, objective and quality of life parameters of the disease.29

SmokingSee the CV risk section.

Sedentary LifestyleIn addition to the benefits of exercise in reducing the prevalence of other diseases, physical exercise also has benefits for AxSpA, improving spinal mobility, physical function, pain and the general condition of the patient; it can also help to reduce inflammation and CV risk factors.30

AlcoholSee the section on GI comorbidities.

Risk of Infections and VaccinationTreatment with certain drugs, such as anti-TNF agents, can increase the risk of infection in these patients, including tuberculosis infection.31 The most frequent infections in patients with AxSpA would be: HBV infection (although its incidence varies according to the country), serious bacterial infections, tuberculosis (TBC), and hepatitis C virus (HCV).3 Cases of tuberculosis infection (TBC) have been described in patients treated with TNF inhibitors, especially with monoclonal antibodies. However, the incidence of TBC in these patients is lower than that of other diseases such as RA or IBD.31

The vaccination status of patients with autoimmune diseases should be assessed at the start of the review. This is essential in patients who are candidates for biological therapies since there can be added immunosuppression, and therefore a vaccination programme should be established beforehand.32

Items on the checklist: vaccinations and screening. The sections included are based on national and international recommendations, and on the document on risk management of biological therapies of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology.32 It involves ruling out any active, systemic or localised infections since it comprises a contraindication at the start of biological therapy, special care should be taken with patients with a history of repeated infections, sepsis or at high risk of infection. Similarly, the adult vaccination calendar should be checked, according to each autonomous region, and it should be completed if not up to date, and patients undergoing biological therapy should not receive live vaccines.

Diphtheria-tetanus-poliomyelitis VaccineCheck whether this vaccine has been given in the past 10 years.

Flu and Pneumococcal VaccineRecommend the annual flu vaccine, and the pneumococcal vaccine.32

Hepatitis B and C Virus and Acquired Immunodeficiency VirusConduct screening, including serological tests to discount chronic infection.

TuberculosisDiscount active and latent TBC, and recent contact with bacilliferous patients. During monitoring, it is recommended that patients should be asked about possible contact, a study performed, and treatment given if necessary.

With regard to practices to avoid: (1) do not give these patients biological therapy in the presence of: active, serious and uncontrolled infections; sepsis or risk of sepsis and TBC, (2) do not give biological treatment to any patient without screening beforehand for chronic HBV, HCV, HIV and TBC.

Pulmonary InvolvementApical pulmonary fibrosis is seen in a small percentage (1%–2%) of patients with long-term spondylitis. They tend to be apical lesions, in pulmonary vertices, generally bilateral. They can form cavities that can be colonised by Aspergillus or Mycobacterium spp.2 Clinically, they can cause cough, dyspnoea, haemoptysis, and the diagnosis is radiological.

Worsening of interstitial lung disease in patients treated anti-TNF agents has been reported with fatal outcomes, although this has been observed more frequently in patients with RA. Given that the risk of anti-TNF therapy on interstitial lung disease has not been completely clarified, it is recommended that the risk/benefit of treatment with these drugs should be assessed on an individual basis.32

Items on checklist: Chest X-ray and assessment of the apices.

Chest X-rayDiscount the existence of infection in apical lesions, especially in patients who require anti-TNF treatment.32

It is also recommended that smoking should be avoided (see the information on smoking in the CV risk section), and strict clinical and lung function monitoring carried out of patients who require initiation of anti-TNF therapy, and in the case of clinical worsening, biological therapy should be discontinued.32

Concomitant MedicationIn general, an exhaustive clinical history should be taken, paying special attention to gathering the patients’ treatment data, to prevent the onset of secondary effects, treatment overlap or interactions.

Items on the checklist: oral anticoagulants, renin–angiotensin system blockers, acetylsalicylic acid and NSAIDs.

Oral AnticoagulantsSpecial caution should be taken when undertaking any intervention in the clinic, and to prevent potential drug interactions, especially with NSAIDs.

Renin–angiotensin System BlockingCombination of drugs useful in the control of blood pressure, reducing CV morbidity and mortality in patients at high risk.33

Acetylsalicylic AcidIn line with the latest EULAR recommendations for the management and prevention of comorbidities, aspirin consumption should be recorded in the history.33

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs/steroidsImportant, due to their possible relationship with AHT, renal function and CV risk.33

Psychoaffective DisordersThe relationship has been described between anxiety and depression and the activity of the disease.34 Up to half the patients have severe fatigue associated with the activity of the disease and with depression, more than half the patients have sleep disorders,35 and up to 34% of males with AxSpA have sexual dysfunction.36

Items on the checklist: measurement of depression, sleep quality and quality of sexual activity.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale37This is a self-report questionnaire with 13 sections, to identify anxiety and depression. A score of between 0 and 7 points is considered to indicate no clear disorder, between 8 and 10 would be doubtful, and scores ≥11 for each of the subscales are probably positive cases.

FatigueThe first item of the BASDAI index or the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-short form (MFSI-SF) are used to assess this parameter.

Sleep DisordersIt was decided to use one of the items of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index38 to evaluate possible sleep disorders; this serves as a first approach and helps to detects problems that require tests in greater depth.

Sexual DysfunctionThe International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)39,40 will be used for men, and some items taken from the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)41 for women (given the lack of short questionnaires, which can really be applied in clinical practice).

Osteoporosis and the Risk of FractureThe systematic review on the incidence of fractures yielded 11 studies,42–52 and concluded that the frequency of vertebral fractures varied a great deal between studies (from 4% to 33%), and that the incidence increases with the course of the disease, from 0.1% to 1.3% after a course of 45 years. A review (manuscript in preparation) of the risk fractures for osteoporosis in spondylitis showed, based on 43 articles analysed, that risk factors for osteoporosis are no more frequent in AxSpA than in other patients, except that there is greater alcohol consumption, and corticosteroids are required. A large part of the risk of spinal fracture in AxSpA patients is due to a biomechanical alteration of the spine that causes a loss of flexibility and makes it behave like a long bone, unable to dissipate the energy of impact.53 Therefore, the most important thing is to avoid falls or hyperextension injuries or direct trauma to the back, but it is also necessary to prevent associated osteoporosis.

Items on the checklist: variables relating to the risk of fracture and use of corticosteroids.

Variables Relating to the Risk of FractureThese include age, weight, alcohol consumption, family and personal history of fracture and radiographic signs of bamboo spine.

Vitamin DThis item was included, only to correct any deficiency.

Warning Signs of Extra-articular ManifestationsThe association between uveitis and AxSpA is well known. A systematic review found a 33.2% prevalence of uveitis in AS.54 Questions about digestive symptoms should form part of the routine assessment of these patients for prompt diagnosis and treatment of this comorbity.55 Aortic root and valve disease, and conduction anomalies are the most important manifestations of heart disease in SA. The myocardium, and exceptionally the pericardium, can also be affected.

Items on the checklist: uveitis, IBD and heart disease.

UveitisAsk about red eye or any loss of vision, as a basic screening method and recommend periodical visits to the ophthalmologist.

Inflammatory Bowel DiseaseIn the clinic, ask about any chronic diarrhoea, pathological products in the stools or the presence of perianal fistulas.

Heart DiseaseThe coexistence of aortic valve disease should be assessed by thorough auscultation, and an atrioventricular block discounted by baseline or annual ECG.

DiscussionRigorous systematic assessment of potential comorbidities can enable earlier detection, which should provide better care outcomes for patients with AxSpA. This document aims to provide this assessment.

We have put the items on to the checklists that all the panellists felt comfortable with, and felt that there were sufficient arguments to keep. Some comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia or cancer, were included initially, but discounted during the second round. Fibromyalgia was rejected as well as other rheumatic diseases, or diseases that involve pain; patients will be examined in the surgery, and the rheumatologist will assess the coexistence of other coinciding rheumatic diseases that might be affecting the patient. With regard to cancer, the incidence of cancer in AxSpA is no different from that of the general population, therefore it was decided not to include it (its management will be similar to that of other patients). Systematic triglyceride testing was also ruled out. The panellists considered that some mention should be made of fertility and pregnancy and, eventually, it was decided that only one reminder should be included on the checklist for patients (“If you are a woman and are planning to become pregnant, inform your doctor so that he/she can choose the best medication for you” (see Fig. 2).

As limitations of these recommendations, we should highlight that the current literature on the management of comorbidities in AxSpA and rheumatic diseases is generally sparse, and heavily biased in favour of research interests. This is why we consider it appropriate to base most decisions on multidisciplinary consensus.

Two checklists were created, and a list of situations to avoid to facilitate the management of AxSpA comorbidities. These recommendations are simple to apply due to their eminently practical format, and are accessible for use in clinical practice. At a later stage, we will test their usefulness and acceptance by a wide group of user that includes doctors, patients and nurses.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that neither human nor animal testing has been carried out under this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have complied with their work centre protocols for the publication of patient data.

Privacy rights and informed consentThe authors declare that no patients’ data appear in this article.

FinancingThis project has been declared of scientific interest by “the holder of the Extraordinary Chair in Inflammatory Autoimmune Diseases, Prof. Luis Carreño”.

This project was financed by Merck Sharp & Dohme Spain. Merck Sharp & Dohme had no influence on the development of the project or the final content of the manuscript.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare in relation to the content of this consensus.

Please cite this article as: González C, Curbelo Rodríguez R, Torre-Alonso JC, Collantes E, Castañeda S, Hernández MV, et al. Recomendaciones para el manejo de la comorbilidad en la práctica clínica en pacientes con espondiloartritis axial. Reumatol Clín. 2018;14:346–359.