The difficulty in diagnosis and the spectrum of clinical manifestations that can determine the choice of treatment for primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) has fostered the development of recommendations by the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER), based on the best possible evidence. These recommendations can serve as a reference for rheumatologists and other specialists involved in the management of APS.

MethodsA panel of four rheumatologists, a gynaecologist and a haematologist with expertise in APS was created, previously selected by the SER through an open call or based on professional merits. The stages of the work were: identification of the key areas for drafting the document, analysis and synthesis of the scientific evidence (using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN] levels of evidence) and formulation of recommendations based on this evidence and formal assessment or reasoned judgement techniques (consensus techniques).

Results46 recommendations were drawn up, addressing five main areas: diagnosis and evaluation, measurement of primary thromboprophylaxis, treatment for APS or secondary thromboprophylaxis, treatment for obstetric APS and special situations. These recommendations also include the role of novel oral anticoagulants, the problem of recurrences or the key risk factors identified in these subjects. This document reflects the first 21, referring to the areas of: diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of primary APS. The document provides a table of recommendations and treatment algorithms.

ConclusionsAn update of the SER recommendations on APS is presented. This document corresponds to part I, related to diagnosis, evaluation and treatment. These recommendations are considered tools for decision-making for clinicians, taking into consideration both the decision of the physician experienced in APS and the patient. A part II has also been prepared, which addresses aspects related to obstetric SAF and special situations.

La dificultad para el diagnóstico y la variedad de manifestaciones clínicas que pueden determinar la elección del tratamiento del síndrome antifosfolípido (SAF) primario ha impulsado a la Sociedad Española de Reumatología (SER) en la elaboración de recomendaciones basadas en la mejor evidencia posible. Estas recomendaciones pueden servir de referencia para reumatólogos y otros profesionales implicados en el manejo de pacientes con SAF.

MétodosSe creó un panel formado por cuatro reumatólogos, una ginecóloga y una hematóloga, expertos en SAF, previamente seleccionados mediante una convocatoria abierta o por méritos profesionales. Las fases del trabajo fueron: identificación de las áreas claves para la elaboración del documento, análisis y síntesis de la evidencia científica (utilizando los niveles de evidencia del Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN]) y formulación de recomendaciones a partir de esta evidencia y de técnicas de «evaluación formal» o «juicio razonado».

ResultadosSe han elaborado 46 recomendaciones que abordan cinco áreas principales: diagnóstico y evaluación, medidas de tromboprofilaxis primaria, tratamiento del SAF primario o tromboprofilaxis secundaria, tratamiento del SAF obstétrico y situaciones especiales. Se incluye también el papel de los nuevos anticoagulantes orales, el problema de las recurrencias o los principales factores de riesgo identificados en estos individuos. En este documento se reflejan las 21 primeras recomendaciones, referidas a las áreas de diagnóstico, evaluación y tratamiento del SAF primario. El documento contiene una tabla de recomendaciones y algoritmos de tratamiento.

ConclusionesSe presentan las recomendaciones de la SER sobre SAF primario. Este documento corresponde a la parte I, relacionada con el diagnóstico, la evaluación y el tratamiento. Estas recomendaciones se consideran herramientas en la toma de decisiones para los clínicos, teniendo en consideración tanto la decisión del médico experto en SAF como la opinión compartida con el paciente. Se ha elaborado también una parte II, que aborda aspectos relacionados con el SAF obstétrico y situaciones especiales.

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disease characterised by the development of deep vein or arterial thrombosis and/or morbidity during pregnancy, associated with the confirmed presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (APA). The APA currently included in the classification criteria are lupus anticoagulant (LA), anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL) and anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies (aβ2GPI)1–3 (Table 1).

Revised antiphospholipid syndrome classification criteria.3

| Clinical criteria |

|---|

| Vascular thrombosis: one or more episodes of arterial, venous or small vessel thrombosis in any organ or tissue of the organism, confirmed by appropriate imaging tests and/or histopathological analysis (the thrombosis must be present without evidence of inflammation of the small vessel)Morbidity during pregnancy:• One or more deaths of a morphologically normal foetus after at least 10 weeks of gestation, with normal foetus morphology documented by ultrasound scan or direct examination of the foetus• One or more premature births of a morphologically normal newborn baby before week 34 of gestation, due to: (1) severe eclampsia or preeclampsia, or (2) recognisable characteristics of placental insufficiency• Three or more consecutive spontaneous abortions prior to week 10 of gestation, having ruled out anatomical and hormonal anomalies in the mother and maternal as well as paternal anomalies |

| Laboratory criteria |

|---|

| Positive results must be obtained in serum or plasma on two or more occasions separated by periods of at least 12 weeks:• Lupus anticoagulant (LA) determined according to the recommendations of the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis• Type IgG and/or IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (aCL) measured by ELISA at medium or high titres (>40 GPL or MPL or >99 percentile)• Type IgG and/or IgM anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies (aβ2GPI) measured by ELISA at medium or high titres (>99 percentile) |

| Definitive APS |

|---|

| Presence of at least one clinical and one laboratory criterion. The laboratory test must be positive in two or more occasions separated by 12 weeks |

APS may present alone, when it is known as primary APS, or it may be associated with other autoimmune diseases, chiefly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It may present exceptionally as multiple thrombi in a short period of time, denominated catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (catastrophic APS), a severe clinical situation with a high mortality rate4 (Table 2).

Preliminary criteria for the classification of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome8

| Diagnostic criteria |

| 1. Evidence of the involvement of three or more organs, systems or tissues2. Development of manifestations simultaneously or in less than one week3. Histopathological confirmation of small vessel occlusion in at least one organ or tissue4. Analytical confirmation of the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant and/or anticardiolipin and/or antiβ2 glycoprotein I antibodies) |

| Definitive catastrophic APS |

| The four criteria |

| Probable catastrophic APS |

| • The four criteria, but only two areas affected• The four criteria, in the absence of analytical confirmation• Criteria 1, 2 and 4.• Criteria 1, 3 and 4 and the development of a third episode from one week to one month after presentation, in spite of anticoagulation; but less than one month, in spite of anticoagulation |

Primary APS is the most common cause of acquired thrombophilia. It is the cause of 10%–15% of all episodes of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), with or without pulmonary embolism; of one third of de novo cerebral accidents in patients under 50 years old, and of 10%–15% of cases of recurring foetal losses.5

Reasonable doubts now exist as to whether thrombotic complications and isolated obstetric morbidity are the manifestations of a single disease, or whether they are two different entities which have the presence of APA in common. While the association of APA with the development of thrombotic phenomena seems to be clear, the link between certain obstetric manifestations and the said antibodies is still the subject of debate.5

Another of the aspects that has yet to be exactly defined is the relevance of the presence of APA in patients who are asymptomatic or lack the manifestations included within the disease criteria. On the one hand, in these clinical situations it is of key importance to gauge the risk of developing APS complications in the future, so that primary prophylactic measures can be implemented in the population in question. The main risk factors identified in these individuals are the APA profile, the presence of cardiovascular risk factors, the presence of other manifestations associated with APS (but not included in the criteria) and suffering another associated autoimmune disease, especially SLE. While these risk factors have been shown to be useful in measuring the risk of thrombosis in this group of APA carrier individuals, their role in developing obstetric manifestations is less clear.6

The experts still feel doubts regarding the optimum treatment for APS.7 These doubts basically arise due to the lack of suitable clinical trials that would make it possible to answer the key questions for this disease: when primary prophylaxis should be started and how long it should last; the optimum treatment for thrombotic phenomena and the different obstetric manifestations; what to do in case of recurrences; the role of direct action oral anticoagulants (DOAC), or how to treat other non-thrombotic manifestations of APS, among many other open questions.

Due to all of the above considerations, it is necessary to establish recommendations based on the latest evidence and the opinions of experts in different specialities for the management and treatment of APS. The purpose of these recommendations is to help doctors in managing the disease, when interpreting the presence of APA as well as when selecting the most suitable therapeutic strategy.

MethodologyDesignThis project used qualitative synthesis of the scientific evidence together with consensus techniques which include the agreement of experts based on their clinical experience and scientific evidence.

Process phasesPreparation of the Recommendations document involved a series of steps, as described below:

- 1.

Creation of the work group. Preparation of the document commenced with the formation of a panel of experts, composed of four rheumatologists who are members of the SER, a haematologist and a gynaecologist. The rheumatologists were selected by open invitation to all of the members of the SER. The Clinical Practice Guides and Recommendations Commission (CPG) of the SER evaluated the curriculum vitae of all of the applicants according to objective criteria based on their contributions to knowledge about APS. This mainly consisted of their participation in high-impact journals during the past 5 years. The clinical and methodological aspects were coordinated, respectively, by a rheumatologist as the chief researcher and a specialist in methodology, a technician of the SER Research Unit.

- 2.

Identification of key areas. All of the members of the work group took part in designing the document and establishing its contents and key aspects. First they identified the clinical research questions that could have the most impact in offering information on the management of APS. They then decided which of these required answering in PICO question format (patient, intervention, comparison and outcome). The methodology to be following in the process of drawing up the recommendations was also defined.

- 3.

Bibliographical search. To answer non-PICO clinical questions a search was undertaken of systematic reviews and updated CPG in Medline and sources that specialise in guides. The other clinical questions were reformulated as four PICO format questions. A search strategy was designed to answer the PICO questions and a review of the scientific evidence in studies published until May 2017 was performed. The following databases were used: Pubmed (Medline), Embase and Cochrane Library (Wiley Online). The process was completed with a manual search of references, posters and conference summaries which the reviewers and experts considered to be of interest.

- 4.

Analysis and synthesis of the scientific evidence. Systematic reviews and CPGs identified for the non-PICO questions were evaluated by the methodological coordinator. It was agreed that only high quality ones would be considered suitable for inclusion as a source of evidence. Several rheumatologists in the SER evidence reviewers work group systematically reviewed the available scientific evidence for the PICO questions. After the critical reading of the complete text of the selected studies for each review they prepared a summary by using a homogenised formula, including tables and text, to describe the methodology, the results and the quality of each study. They described the reasons for the exclusion of the papers that were not included in the selection. The overall level of scientific evidence was evaluated using the levels of evidence of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)9 (see Appendix B).

- 5.

Preparation of recommendations. After the critical reading, the chief researcher and the members of the group of experts formulated the specific recommendations based on the scientific evidence. This formulation was based on the “formal evaluation” or “reasoned judgement”, having previously summarised the evidence for each one of the clinical questions. The quality, quantity and consistency of the scientific evidence were also taken into account, together with the generality of the results, their applicability and clinical impact. The recommendations were graded using the SIGN9 system (see Appendix B). The recommendations were divided into five main areas: diagnosis and evaluation, primary thromboprophylaxis, treatments of primary APS or secondary thromboprophylaxis, treatment of obstetric APS and special situations.

- 6.

External review. After the previous phases a final draft version of the document was prepared. This was sent to professionals selected for their knowledge of APS for a phase of independent external revision. The ultimate aim of this was to increase the external validity of the document and ensure the exactitude of its recommendations.

- 7.

Public exhibition. The draft of the SER Recommendations document was shown to members of the SER and other interested parties (the pharmaceutical industry, other scientific associations and patients’ associations) to gather their opinions and scientific arguments respecting its methodology and recommendations. No statements were received in response to this.

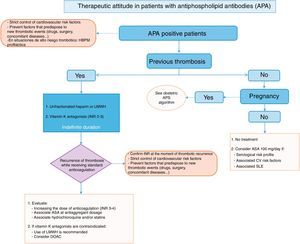

The document contains recommendations which are subdivided into the different areas described above. Treatment algorithms have been prepared on the basis of the recommendations, showing the approach to treating APS in summarised form.

ResultsThere are 46 recommendations on primary APS, and they cover five main areas: diagnosis and evaluation, primary thromboprophylaxis, the treatment of primary APS or secondary thromboprophylaxis, the treatment of obstetric APS and special situations. This document contains the first 21 recommendations, which are in the areas of diagnosis and evaluation, primary thromboprophylaxis and the treatment of primary APS or secondary thromboprophylaxis (Table 3).

SER recommendations for primary antiphospholipid syndrome (part 1).

| Diagnosis and evaluation | GR |

|---|---|

| Recommendation: in patients with APS the simultaneous detection of the three antiphospholipid antibodies included in the classification criteria is recommended (LA, aCL and aβ2GPI) to establish the risk of thrombosis or obstetric complications | C |

| Recommendation: there is a higher risk of clinical manifestations of APS when lupus anticoagulant or more than one antiphospholipid antibody is detected (double and most particularly triple positivity) in the same patient | B |

| Recommendation: in habitual clinical practice, in the general population with the suspicion of APS or in patients already diagnosed with the disease, the detection of antiphospholipid antibodies not included in the classification criteria is not recommended | D |

| Recommendation: the detection of antiphospholipid antibodies is not recommended if the patient is anticoagulated and diagnosed | √ |

| Recommendation: in patients with induced thrombosis, a low profile of thrombotic risk and without conventional cardiovascular risk factors, the repetition of antibody determination may be considered to evaluate the need for indefinite anticoagulation | √ |

| Recommendation: a repeat of the determination of the antiphospholipid antibodies included in the classification criteria is recommended (except for lupus anticoagulant), at least at 12 weeks | √ |

| Recommendation: if lupus anticoagulant was positive in the initial diagnosis and it is wished to confirm this, individualising each patient according to the risk of thrombosis, it is recommendable to suspend oral anticoagulation at least 1 or 2 weeks prior to determination, using a therapeutic dose of heparin (associated with an antiaggregant dose of acetylsalicylic acid case of previous arterial thrombosis) suspending it the night before the determination to prevent interference in the laboratory results | √ |

| Primary thromboprophylaxis | |

|---|---|

| Recommendation: in patients who are antiphospholipid antibody carriers, without clinical signs associated with APS, specific prophylactic treatment is recommended with low molecular weight heparin in situations of high thrombotic risk (prolonged immobilisation, recent surgery, puerperium or ovary stimulation, etc.) | C |

| Recommendation: in patients with a low risk profile prophylactic treatment is only recommended when associated cardiovascular risk factors are present. Low doses of acetylsalicylic acid should be used, while treating or correcting the cardiovascular risk factors | C |

| Recommendation: in patients who are carriers of antiphospholipid antibodies and associated thrombocytopenia, prophylactic treatment with low doses of acetylsalicylic acid is recommended | C |

| Recommendation: in patients with a medium/high risk prophylactic treatment during an indefinite time is recommended with low doses of acetylsalicylic acid | C |

| Recommendation: in patients who are carriers of antiphospholipid antibodies and without clinical signs associated with APS and who wish to conceive, it is recommended to evaluate prophylactic treatment with low doses of acetylsalicylic acid, according to their risk profile | C |

| Treatment of primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Secondary thromboprophylaxis | |

|---|---|

| Recommendation: patients with antiphospholipid antibodies and with a first episode of venous thrombosis should be treated with unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin followed by vitamin K antagonists | D |

| Recommendation: in the secondary prevention of venous thrombosis anticoagulation in a therapeutic range for an INR of 2–3 is recommended | D |

| Recommendation: in the secondary prevention of venous thrombosis anticoagulation during an indefinite time is recommended | D |

| Recommendation: patients with primary APS and previous arterial thrombotic events should be treated with standard anticoagulation (INR 2–3) to prevent the recurrence of arterial thrombosis | B |

| Recommendation: in thrombotic APS that is refractory to conventional treatment it is recommended to associate antiaggregant doses of acetylsalicylic acid, hydroxychloroquine or statins to the conventional therapy | D |

| Recommendation: when there is a formal contraindication against oral anticoagulants low molecular weight heparin is recommended as the alternative therapy | D |

| Recommendation: if recurring arterial thromboses occur while receiving standard anticoagulation, the treatment may be optimised by adding antiaggregation or increasing the anticoagulation dose (INR 3–4) | D |

| Recommendation: in refractory thrombotic APS as well as the conventional treatment it is recommended that cardiovascular risk factors be strictly controlled, while avoiding situations that predispose to new thrombotic events | D |

| Recommendation: direct action oral anticoagulants may be a good alternative in patients with venous thrombosis who are allergic to dicumarinics and/or difficulty in maintaining their INR in a therapeutic range with vitamin K antagonists | √ |

aβ2GPI: anti-b2-glycoprotein I; aCL: anticardiolipin antibodies; LA: lupus anticoagulant; GR: grade of recommendation (see Appendix B); APS: antiphospholipid syndrome.

Which of the APA included in the classification criteria (LA, aCL and aβ2GPI) are the ones with the highest risk of developing venous and/or arterial thrombosis and obstetric complications?

Recommendation:in patients with APS it is recommended that all three APA included in the classification criteria should be detected simultaneously (LA, aCL and aβ2GPI) to establish the risk of thrombosis or obstetric complications (grade C recommendation).

Recommendation:there is a higher risk of presenting clinical manifestations of APS when lupus anticoagulant or more than one different APA is detected (double and in particular triple positivity) in the same patient (grade B recommendation).

The clinical manifestations of APS are associated with the detection of APA. APA may be detected by the prolongation of phospholipid dependent coagulation tests, which is denominated lupus anticoagulant (LA), or by solid phase assays such as ELISA for aCL, IgG and/or IgM or aβ2GPI, Ig and/or IgM. APS classification criteria currently only include the detection of these APA. A patient fulfils the laboratory criterion when at least one of these APA is detected in serum or plasma, on two or more occasions at least 12 weeks apart. Nevertheless, the risk of thrombosis or obstetric complications may differ depending on whether one of these antibodies or a combination of the same is detected.

Recurrent abortions occur the most frequently in patients with type IgG and/or IgM aCL10,11(LoE 2++) or AL12,13(LoE 2−). aβ2GPI type IgG and/or IgM antibodies are associated with a higher rate of foetal losses11,14,15 than is the case with aCL and AL,16 and especially with a higher risk of late foetal losses12(2−). The majority of studies find that the detection of more than one APA in the same patient indicates an increased risk of recurring abortions.10,13,15–19(LoE 2++, 2+, 2−, 3)

Recurring venous and/or arterial thromboses are more frequent in patients with AL20–28(LoE 2++, 2+, 2−), aCL antibodies16,21,22,26,29–35(LoE 2++, 2+, 2−, 3) or aβ2GPI antibodies21,22,24,27,28,33,36–39(LoE 2++, 2+, 2−). The detection of more than one APA in the same patient indicates an increased risk of recurring venous and/or arterial thrombosis,24,25,37,39 in particular triple positivity for LA, aCL and aβ2GPI.16,23,24(LoE 2++, 2+)

In the light of these studies the preparatory group considers that in patients with APS the risk recurrent abortions and venous and/or arterial thrombosis is greater when different APA are detected in the same patient. The results of the different studies are consistent, and the majority suggest detection of all the APA included in the classification criteria (LA, aCL and aβ2GPI).

The preparatory group also understands that the results of the studied analysed are directly applicable to our medical system, as it is possible for all hospitals and speciality centres to detect the APA included in the classification criteria (LA, aCL and aβ2GPI).

Detecting more than one APA makes it possible to select the subgroup of patients with APS and the highest risk of recurring abortions and recurring venous and/or arterial thrombosis, with the resulting implications for prognosis and treatment.

Antiphospholipid antibodies which are not included in the classification criteriaWhen is it necessary to detect the APA that are not included in the current APS classification criteria?

Recommendation:in normal clinical practice, in the general population with the suspicion of APS or in patients already diagnosed with the disease, it is not recommended to detect the APA that are not included in the classification criteria (grade D recommendation).

The Sydney classification criteria only include three of the known APA: LA, the aCL (IgM and IgG) and the aβ2GPI (IgM and IgG). Detection of the other APA is still not indicated in medical care. There is insufficient information about their clinical significance, although many of the new APA described are potentially important in the physiopathology of APS, and currently it is not known whether they should be included in the diagnostic algorithm and routine study of patients with APS.

The most relevant of the new APA are described below, in terms of their involvement in thrombosis or obstetric problems.

aβ2GPI domain 1 antibodiesRecent studies have described a higher prevalence and higher titres of domain 1 of aβ2GPI antibodies in patients with multiple APAs, and several multicentre studies associate these with thrombosis and venous thrombosis above all. Detecting them has been suggested as a means of evaluating the risk of thrombosis in patients with APA, although studies are required to validate this.40–42(LoE 3, 4)

Isotypes IgA aCL and aβ2GPIThe IgA isotypes of the aCL and aβ2GPI may be of use in the diagnosis of seronegative APS, defined as clinical manifestations of the APS in the repeated absence of APA detected using routine techniques. Thus even though there is controversy on this point, some international experts advise requesting them when studying patients with the suspicion of seronegative APS.43(LoE 4)

Anti-prothrombin and anti-phosphatidylserine/prothrombin complex antibodiesAnti-prothrombin antibodies are detected directly on the plate, either against prothrombin or against the phosphatidylserine/prothrombin complex (aPS-PT). Although they may coexist in the same patient, these are different antibodies. The detection of aPS-PT antibodies is associated with a higher risk of thrombosis, and most especially with a higher risk of obstetric complications, although there role in the diagnosis of APS has yet to be defined.44,45 Recent data from a multicentre study have shown that phosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex IgG antibodies are one of the candidates for future inclusion in APS classification criteria.46

Anti-phosphatidylethanolamine antibodiesThe presence of anti-phosphatidylethanolamine antibodies (aPE) has been found to be associated with manifestations of thrombosis as well as obstetric morbidity. A multicentre study that evaluated the prevalence as well as the clinical and biological significance of aPE in 270 patients with thromboembolic events analysed their association with patients that presented the APA included in the criteria and fulfilled the APS classification criteria. 15% of the patients with thrombosis presented aPE, in comparison with 3% of the controls (P<.01). In 63% of the patients with aPE and thrombosis, the tests to determine APA were negative. The authors of this work concluded that there is a strong association between aPE and the risk of thrombosis, suggesting the possible usefulness of detecting this antibody in patients with thrombosis in which the APA are negative.47–50 Nevertheless, as is the case for the other antibodies that are not included in the classification criteria, their role in the diagnosis of APS has yet to be clearly defined APS.47–50

Anti-vimentin antibodiesThese antibodies activate the platelets and leukocytes. They increase p-selectin and are able to bind to cardiolipin.51,52 Patients with antibodies against the cardiolipin/anti-vimentin complex may present clinical manifestations of APS, although they are also detected in patients with other autoimmune diseases.

Anti-annexin A5 and anti-annexin 2 antibodiesAnti-annexin A5 antibodies have been linked to obstetric complications,53–55 and some studies have linked them to thrombosis, although their role in APS has not been established.54

Annexin 2 is a co-factor in plasmin generation and it has fibrinolytic activity.56–58 Anti-annexin 2 antibodies have been detected in patients with APS, and they may play a pathogenic role.56–58

Anti-protein SThese alter the function of protein S, and some studies connect them with a higher risk of venous thrombosis, although no high-quality studies have been conducted in patients with APS.59

Current evidence respecting the APA which are not included in the classification criteria is based on observational or cohort studies with few patients, and this hinders establishing recommendations for their detection and definitive inclusion in the APA panel. Laboratory detection techniques would have to be standardised prior to determining their clinical applicability. At a clinical level studies with more clinical evidence are needed to establish whether they should be included in the diagnostic criteria for APS.59,60

Anticoagulated patients with primary antiphospholipid syndromeWhich antiphospholipid antibodies can be used and when for the diagnosis and follow-up of an anticoagulated patient with APS?

Recommendation:the detection of antiphospholipid antibodies is not recommended if the patient is anticoagulated and diagnosed (grade √ recommendation).

Recommendation:in patients with induced thrombosis, a low risk profile for thrombosis and without conventional cardiovascular risk factors, antibody detection test repetition may be considered to evaluate the need for indefinite anticoagulation (grade √ recommendation).

Recommendation:it is recommended to repeat the determination of the antiphospholipid antibodies included in the classification criteria (except for lupus anticoagulant) at least at 12 weeks (grade √ recommendation).

Recommendation:if lupus anticoagulant was positive in the initial diagnosis and confirmation is required, individualising each patient according to their risk of thrombosis, it is recommendable to suspend oral anticoagulation at least 1 or 2 weeks before the determination, using heparin at a therapeutic dose (associated with acetylsalicylic acid at anti-aggregant dose levels in the case of previous arterial thrombosis) and suspending it the night prior to determination to prevent interfering with the laboratory results (grade √ recommendation).

APA is determined at least once for the majority of patients who develop thrombosis. However, once they are anticoagulated the experts agree that it is necessary to perform a new determination at 12 weeks, to comply with the Sydney criteria and ensure that the diagnosis of APS is correct. There is no inference between the aCL and aβ2GPI antibodies and anticoagulants, and tests for them can be repeated under anticoagulation. Nevertheless, in the case of LA there is interference at the level of laboratory testing, and interpretation may be erroneous in the presence of anticoagulants. International agreements therefore recommend determining LA without the presence of anticoagulants, so that anticoagulation in patients taking vitamin K antagonists (VKA) should be suspended during 1–2 weeks, switching to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) during this time at a therapeutic dose and suspending it 12h before the test.61,62

There are also two studies which were performed to validate LA detection tests in anticoagulated patients. They conclude that in the clinical situation in which an anticoagulated patient at high risk of thrombosis requires confirmation of LA positivity, it is possible to consider using the Taipan snake venom time test with Ecarin time to confirm their positivity and thereby avoid suspending anticoagulation. Nevertheless, in spite of its high specificity its sensitivity is low, and it is not available in all coagulation laboratories for routine determination. In any case, the clinical criterion should prevail, and the panel considers that for a patient at high risk of thrombosis it is not absolutely necessary to confirm LA to diagnose the disease.63,64

It is also important to monitor VKA in patients with APS, as different studies show that in patients with APS there is a phenomenon of warfarin resistance, and that given the interferences at the level of INR detection, it is considered to be important for anticoagulated patients to maintain an INR≥3. This parameter should be determined by using a citrated tube in the laboratory. In the case of recurring thrombosis events the studies conclude that determination of an anti-Xa should be performed to evaluate the real levels of anticoagulation. Moreover, at the current time finger-prick checks are less reliable than those using venous puncture.61,65–69

There is little evidence for the clinical significance of APA in monitoring APS in anticoagulated patients.65–69 A prospective study of patients who were anticoagulated due to arterial disease compared warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of ictus relapse, with a follow-up time of 2 years.69 There were no significant differences between the patients with or without positive APA, although patients with APA have a higher rate of events (31.7%) than those who do not have APA (24%). The authors conclude that although detecting APA without subsequent confirmation does not identify high risk patients, double positivity does identify these high risk patients. They also conclude that APA should be studied for young ictus patients.69

The relevance of these studies is based on improving knowledge about the complexity of monitoring anticoagulation in APS patients. It is not indicated to perform APA tests on anticoagulated patients indefinitely for their follow-up or during anticoagulant treatment. There are no data that would bring about a change of therapeutic attitude: it only identifies the patients who are at a high risk of relapse.70

Nor are there data on the usefulness of determining APA in patients with induced thrombosis, although given the risk of haemorrhage associated with VKA, in some cases monitoring may be individualised to determine whether patients need indefinite anticoagulant treatment or not.71,72

To summarise, some studies show how difficult it is to measure LA in the presence of anticoagulants, for diagnosis as well as when monitoring. Although it is possible to measure the other APA (IgM and IgG), there is no consistent evidence for their usefulness in long-term monitoring or that this gives rise to greater risk or a change of therapeutic attitude.

Primary thromboprophylaxisIn patients with APA who do not fulfil APS criteria, which prophylaxis is the most effective?

Recommendation:in patients who are carriers of antiphospholipid antibodies and without symptoms associated with APS, prophylactic treatment is recommended with low molecular weight heparin in situations with a high risk of thrombosis (prolonged immobilisation, recent surgery, during the puerperium or ovary stimulation, etc.) (Grade C recommendation).

Recommendation:in low-risk profile patients prophylactic treatment is only recommended when there are associated cardiovascular risk factors. This should consist of low doses of acetylsalicylic acid and correction or treatment of the cardiovascular risk factors (grade C recommendation).

Recommendation:in patients who are carriers of antiphospholipid antibodies and with associated thrombocytopenia, prophylactic treatment is recommended with low doses of acetylsalicylic acid (grade C recommendation).

Recommendation:in patients with a medium to high risk profile prophylactic treatment is recommended with low doses of acetylsalicylic acid during an indefinite period of time (grade C recommendation).

Recommendation:in patients who are carriers of antiphospholipid antibodies, without symptoms associated with APS and who wish to conceive, it is recommended that prophylactic treatment with low doses of acetylsalicylic acid be considered, according to their risk profile (grade C recommendation).

At the current time, the risk of thrombosis in individuals who are carriers of APA (fulfilling the serological criteria), without associated symptoms, is not well established. The data obtained in series of patients with highly heterogeneous characteristics varies in rates of annual incidence from 0% to 7.4%.6,73 APA are common in the general population, and not all carriers run the same risk of developing manifestations of the disease in the future.74 Of all the risk factors for developing clinical APS, the experts agree that four of them are fundamental, and that these should guide the classification of APA carrier individuals when deciding whether or not primary prophylaxis is necessary.34,74–77 These four factors are the APA profile, the presence of cardiovascular risk factors, the presence of other manifestations associated with APS (and not included in the criteria) and the fact of suffering another associated autoimmune disease, especially SLE (Table 4). While these risk factors have been shown to be of possible use in grading the risk of thrombosis in this group of APA carriers, their role in the risk of developing obstetric manifestations is not equally clear.6

Clinical and serological risk factors for the development of clinical manifestations in patients who are carriers of antiphospholipid antibodies.

| Clinical risk factors |

| Classical cardiovascular risk factors |

| Smoking |

| AHT |

| Dyslipidemia |

| Associated autoimmune disease |

| SLE |

| Manifestations associated with APS |

| Thrombocytopenia |

| Serological risk factors |

| High risk profile |

| Positive LA |

| Triple positivity (LA+aCL+aβ2GPI) |

| Persistent positive aCL at medium-high titre |

| Low risk profile |

| Intermittently positive aCL or aβ2GPI at medium-low titres |

aβ2GPI: anti-β2 glycoprotein I; aCL: anticardiolipin antibodies; LA: lupus anticoagulant; AHT: arterial hypertension; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus.

Prepared by the authors. Modified Ruiz-Irastorza et al.74 serological factors.

Although controversy clearly exists as to which APA positive patients should receive primary prophylaxis, the majority of experts agree that prophylaxis should be administered to all of these patients during high risk situations for thrombosis (prolonged immobilisation, recent surgery, pregnancy and the puerperium, ovary stimulation and nephrotic syndrome, etc.).6,74 This recommendation is based on the data of two observational studies in which APA positive patients without associated clinical signs showed a significant reduction in thrombosis events during monitoring when they were only given prophylaxis during risk situations (surgery or immobilisation).25,78(LoE 2+)

There is now only one clinical trial that covers primary prophylaxis in APA carrier patients. The clinical trial by Erkan et al.79 included 98 APA positive patients, with or without systemic autoimmune disease, who were randomised and received acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) (81mg/day) or a placebo, before being followed up for 3 years. This trial did not find a favourable result for primary prophylaxis with ASA. Three of the 48 patients with ASA had thrombosis (2.75 cases per 100 patients-years) vs none for the 50 control patients, giving a HR of 1.04 (CI 95%: 0.69–1.56; P=.830) (LoE 1+). Nevertheless, this study has been broadly criticised by experts, and it has numerous limitations. The small number of patients included, the short follow-up of the same, the APA profile of the patients and the high proportion of patients with SLE mean that the results of this work should be interpreted extremely cautiously.6 In spite of its limitations, the majority of experts consider that chronic treatment with prophylactic doses of ASA in APA carrier individuals with a low risk profile is not justified.6,74

Arnaud et al.80 carried out a meta-analysis of observational studies, asking the authors of the studies for the data of individual patients to determine whether ASA has a protective effect against the risk of a first thrombosis in APA positive patients without the clinical criteria for APS. 5 studies of international cohorts were included, with a total of 497 subjects and 79 cases of a first thrombosis (3469 patients-years of follow-up). After adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors, APA profiles and treatment with hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), the HR for a first thrombosis of any type in individuals treated with low doses of ASA vs those who were not treated was 0.43 (CI 95%: 0.25–0.75). Analysis of subgroups according to the type of thrombosis showed that ASA has a protective effect against arterial thrombosis (HR: 0.43; CI 95%: 0.20–0.93) but not venous thrombosis (HR: 0.49; CI 95%: 0.22–1.11). The analysis of subgroups depending on the underlying disease showed that ASA has a protective effect against arterial thrombosis in patients with SLE (HR: 0.43; CI 95%: 0.20–0.94) and in asymptomatic carriers (HR: 0.43; CI 95%: 0.20–0.93) (LoE 2++). In a prospective observational study81 that included asymptomatic individuals who were carriers of APA, and after a 9-year follow-up, the main factors identified as associated with the development of thrombosis were double/triple APA positivity, the presence of classical cardiovascular risk factors (smoking) and the concomitant presence of other autoimmune diseases. In this study prophylaxis during risk situations was associated with less development of thrombosis.81(LoE 3)

Thus although it is not possible to recommend primary prophylaxis for all APA carrier individuals, according to the little evidence that is available, all of the experts agree on the need to grade the risk of thrombosis according to the parameters defined above, as well as the correction and treatment of classical cardiovascular risk factors. They also agree on the need for primary indefinite prophylaxis with antiaggregant doses of ASA in individuals who are considered to be at risk.6,74 This risk group should include patients who have an associated autoimmune disease, especially SLE.74

Thrombocytopenia is the only one of the several clinical manifestations associated with APS but which are not included in the classification criteria for the disease which has been shown most conclusively to be associated with a higher risk of thrombosis.75,82–84 In other manifestations, such as cardiac or cutaneous involvement, it has not been possible to conclusively demonstrate such a clear association with the development of clinical or obstetric thrombosis.

To date no well-designed study has evaluated the efficacy of anticoagulation in APA patients without any associated clinical signs. Only one study conducted in a different population (purely obstetric APS and patients with SLE) compared this treatment with ASA associated with low intensity anticoagulation (INR 1.5) vs antiaggregant doses of ASA for the primary prophylaxis of thrombotic phenomena.73 In spite of the limitations of the study, no significant differences between both treatment groups were found in terms of the prevention of thrombotic events. However, the group that included low intensity anticoagulation had a higher number of episodes of bleeding.

While there is little information about primary thromboprophylaxis in APA carriers, even fewer studies have been published on prophylaxis for obstetric complications. Women with obstetric APS are currently considered to be at greater risk of developing thrombosis in the future.85 While treatment with heparin associated with ASA seems to be effective in the prevention of early foetal loss,86,87 this combination has not been proven to be effective in preventing late complications of the disease.86–88 The clinical situation in question – primary prophylaxis in women who are APA carriers – is hard to define at the current time due to the lack of studies in this population. While on the one hand APA detection is not usually requested for women who have not previously shown clinical signs of obstetric involvement, on the other hand the few studies which are available cover an extremely heterogeneous population, and several studies include patients with SLE and other autoimmune diseases.89(LoE 1+)

The study by Amengual et al.89 was a systematic recent review which analysed 154 pregnancies (92 with a prophylactic treatment and 62 with no treatment). It concluded that there is now no evidence that prove that giving prophylactic doses of ASA is better than a placebo or normal care to prevent unfavourable obstetric results during the first pregnancy of healthy women who are APA carriers.90–92 A recent study that has only been published in abstract form93 reviewed 70 pregnancies in 62 women who are APA carriers. The factors associated with a poorer obstetric prognosis were triple positivity for APA, the presence of acquired risk factors (fundamentally cardiovascular risk factors), the presence of manifestations associated with APS and lupus-like manifestations. Curiously, the patients with the worst obstetric prognosis were also more likely to receive combined therapy of low dose ASA and heparin.

Treatment of primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Secondary thromboprophylaxisPrimary antiphospholipid syndrome and venous thrombosisWhat is the treatment for venous thromboembolic disease?

Recommendation:patients with antiphospholipid antibodies and who have had a first episode of venous thrombosis should be treated with unfractionated heparin or low molecular weight heparin, and then by vitamin K antagonists (grade D recommendation).

Recommendation:for the secondary prevention of venous thrombosis anticoagulation is recommended in a therapeutic range for an INR of 2–3 (grade D recommendation).

Recommendation:for the secondary prevention of venous thrombosis anticoagulation is recommended for an indefinite time (grade D recommendation).

The most common form of venous thrombosis in APS is DVT with or without associated pulmonary embolism. The recommendations of groups of experts conclude that the treatment for acute venous thrombosis in APS is the same as it is for other patients with venous thrombosis, consisting of anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin or LMWH during at least 5 days, followed by a VKA.94(LoE 4)

Long-term treatment and the duration and intensity of anticoagulation are essential aspects that were reviewed in the literature. Nevertheless, there is little published scientific evidence regarding them.95–101

Firstly, retrospective studies undertaken in APS patients suggested that intense anticoagulation (INR≥3) is more effective than treatment using standard lower ranges.102 Two subsequent randomised clinical trials (RCT) did not confirm that this range of anticoagulation was better than the standard to obtain an INR of 2–3.103,104 Both studies were designed to demonstrate that anticoagulation with warfarin to obtain high ranges is better than a more moderate range in preventing recurrent thrombosis. In the first trial, 114 patients with APS (74% with previous venous thrombosis) were randomised and followed-up for an average of 2.7 years. The incidence of recurrent thrombosis was 10.7% in the patients treated with high range anticoagulation, vs 3.4% in the group treated with a moderate range (HR 3.1; CI 95%: 0.6–15). The risk of bleeding was comparable in both groups (5.4% in the high range group and 6.9% in the moderate range anticoagulation group; HR 1; CI 95%: 0.2–4.8). Overall, the proportion of haemorrhaging complications was also similar: 25% and 19% of the patients, respectively (HR 1.9; CI 95%: 0.8–4.2). Nevertheless, the study included a very heterogeneous group of patients; the majority of them only had isolated positive aCL IgG or LA, and they had a broad age range. Thus few patients at high risk of having more than one subtype of APA were included. In the second trial, 109 patients with APS (89% with previous venous thrombosis) were randomised and followed-up during an average of 3.6 years. The incidence of recurrent thrombosis amounted to 11.1% in the patients treated with high range anticoagulation, vs 5.5% of the group treated with a moderate range (HR 1.97; CI 95%: 0.49–7.89). Nor did the risk of bleeding differ between both groups (27.8% vs 14.6%; HR 2.18; CI 95%: 0.92–5.15). When the results of both trials were combined in a meta-analysis using the Peto method105 a significant increase was detected in the risk of slight bleeding in the patients treated with high dose anticoagulation (OR 2.3; CI 95%: 1.16–4.58; P=.02). The accumulated data did not show differences in the risk of thrombosis recurrence (high range vs moderate range; OR 2.49; CI 95%: 0.93–6.67), overall bleeding (OR 1.73; CI 95%: 0.93–3.31) or major bleeding (OR 0.73; CI 95%: 0.23–2.31). These results were subsequently endorsed by the recommendations of experts following the 13th International APA Congress.74

The systematic review conducted by Ruiz-Irastorza et al.106 includes 16 papers: 9 retrospective studies and prospective cohort studies,78,102,107–112 5 analyses of subgroups70,113–116 and 2 RCT.103,104(LoE 1+, 2+) Although this has the limitations intrinsic to the inclusion of studies with different designs, as it is less restrictive in its inclusion criteria it establishes conclusions that are more extrapolatable. The main conclusions of this review are that, in the case of venous thrombosis, secondary prophylaxis should be undertaken using standard range anticoagulation to reach an INR 2–3. Only in the case of recurring venous thrombosis, and according to the results of the cohort studies, is it recommended to anticoagulate at sufficient doses to maintain an INR≥3. On the other hand, one study showed that low intensity anticoagulation with an INR<1.9 does not properly prevent the risk of recurrence.111 The risk of major bleeding due to anticoagulation stands at from 2% to 3% per year,100 concluding that the recurrence of thrombosis is more frequent and leads to a higher mortality than the haemorrhaging complications caused by warfarin.

All of the works in the literature published on the treatment of venous thrombosis in APS refer to warfarin. However, in our context acenocumarol is the drug used preferentially. Although there is no study which specifically compares their efficacy in APS, other publications cover other clinical situations from which it is possible to extrapolate as they are similar, given that the mechanism of action is the same but with different pharmacokinetics.117,118

Different aspects have to be considered in connection with the duration of anticoagulant treatment, such as whether venous thrombosis is spontaneous or caused by other risk factors (e.g., immobilisation or oral contraceptives, etc.), the location of the venous thrombosis and its extension (DVT with or without pulmonary embolism) or the APA profile, among others.

In spite of the variability of the recommendations published for the secondary prevention of venous thrombosis in APS patients, all of the authors agree that the risk of recurrence is high in uncoagulated patients with APS, so that they recommend prolonged anticoagulation.

In a prospective study,116 105 patients with a single positive determination of aCL were randomly assigned to a group in which warfarin was suspended after 6 months of treatment. They suffered 23 recurrences vs 3 in the group of 106 patients treated indefinitely (HR 7.7; CI 95%: 2.4–25). All of the patients who suffered recurrence in the indefinitely treated group had suspended the treatment prior to the event. Nevertheless, this study has major limitations such as the fact that aCL were only determined once and that titres were low in 88% of cases. It may therefore be the case that some patients lacked APS classification criteria. A second prospective observational study119 which determined the presence of aCL and LA after the first episode of venous thrombosis found a HR of 4 for recurrence at 3 months (CI 95%: 1.2–13) in APA positive patients vs those who were APA negative. Although these patients received anticoagulant treatment, the incidence of recurrent thrombosis was higher in the APA positive patients vs those who were not. Prospective studies in patients with APS treated with antithrombotic therapy show an incidence of thrombosis recurrence of from 3% to 24% per year,31,70,103,104 while in other retrospective studies the range was higher (53%–69%).102,111 The latest recommendations of the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) conclude that in patients with non-induced proximal DVT or pulmonary embolism (in the absence of factors such as pregnancy, hormone therapy, immobilisation or recent surgery) anticoagulation should be maintained indefinitely.120 The general consensus is therefore that patients with APS and venous thrombosis should be treated indefinitely with anticoagulation.94

Nevertheless, these recommendations are of limited strength according to some authors, due to the low quality of the studies involved and their methodological limitations.121

The scenario is different for patients with persistently negative APA counts for years after suffering a thrombotic event, and in this situation it is unknown whether or not it is safe to suspend anticoagulation.122,123

Primary antiphospholipid syndrome and arterial thrombosisWhat is the treatment for arterial thromboembolic disease in a patient with APS?

Recommendation:patients with primary APS and previous arterial thrombotic events should be treated with standard anticoagulation (INR 2–3) to prevent recurrences of arterial thrombosis (grade B recommendation).

The treatment of arterial thrombosis in patients with APS is still controversial as to whether it should consist of platelet anti-aggregation, anticoagulation or both. In the case of anticoagulation there is debate about whether a dose to maintain an INR of 2–3 or a stronger dose should be used.

The management of arterial thrombosis and more specifically cerebral ischaemia is highly controversial in APS patients. This difficulty arises due to several factors, including the lack of well-designed randomised prospective studies; the fact that the majority of studies fail to differentiate between venous and arterial thrombosis; methodological and therapeutic heterogeneity, and lastly that the laboratory diagnosis of APS is not always carried out strictly in accordance with the classification criteria. Thus as little scientific evidence is found for this question and no primary studies were identified which were specifically designed to answer it, a parallel search was added to the initial search strategy. However, the papers found in the parallel search also failed to answer the clinical question, so they were not included. In the studies that were found it was impossible to obtain individualised data according to thrombosis type (venous or arterial) as they were designed to evaluate the efficacy of thrombosis treatment in general for patients with primary APS.

Due to the above reason, the preparatory group decided to eventually include studies which either do not distinguish between venous and arterial thrombosis, as well as ones that include only patients with venous thrombosis or with arterial thrombosis, but which do not distinguish between primary APS or APS that is secondary to SLE.70,103,104,124

The Antiphospholipid Antibodies and Stroke Substudy (APASS), conducted in the context of the Warfarin vs Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study (WARSS) clinical trial, found no significant differences between the use of anti-aggregation with ASA and warfarin in the prevention of thrombotic events, although it did not distinguish between venous and arterial thromboses. Even in this work the authors found that the presence of APA was not a predictive factor for the recurrence of thrombosis.70(LoE 1+)

At first, retrospective studies carried out in patients with APS suggested that intense anticoagulation (INR≥3) is more effective than treatment using lower standard ranges.106 No differences were found between high range anticoagulation with warfarin (for an INR of 3–4) and standard range (INR 2–3) in two clinical trials which did not discriminate between arterial and venous thromboses. These studies also had the limitation that their evidence could not be extrapolated to patients with previous arterial thrombotic events, as they excluded patients with previous ictus and those with recurrent thrombosis while anticoagulated.103,104 A secondary analysis of these trials shows that high range anticoagulation (INR 3–4) may reduce the risk of recurrence of thrombotic events in patients with APS. Nevertheless, this conclusion is controversial. On the one hand, when the results of both unique clinical trials are analysed together103,104 paradoxically a slight increase is observed in recurrences in patients treated using high range anticoagulation (INR 3–4), although this is not statistically significant (LoE 1+). However, the systematic review by Ruiz-Irastorza et al.106 presents a sub-analysis of the INR at the moment of recurrence of the thrombosis in the works that give this datum. These studies are heterogeneous and the author concludes that the majority of recurrences occur at an INR lower than 3, and suggests that intense anticoagulation may be a better option for the prevention of the said recurrences (LoE 1+).

More specifically, the conclusions regarding the management of cerebral ischaemia are based on studies that include patients with ictus of any origin, with overall analysis of the therapy and without distinguishing between primary APS or APS secondary to SLE. In general no significant differences were found between the use of anti-aggregation with ASA and standard range anticoagulation with warfarin. Nevertheless, in patients with primary APS and a history of a previous ischaemic cerebrovascular event, the combined therapy of ASA and standard range anticoagulation (INR 2–3) is effective in the secondary prevention of recurrences.124(LoE 1−)

Although the evidence is limited, the studies also show that the risk of recurrent thrombosis and mortality due to thrombosis is greater than the risk of mortality due to haemorrhaging in patients with APS who receive anticoagulation, even in the range INR 3–4.102–104,106,107,111,116

Lastly, a recommendations document was identified which had been prepared by the American association for the study of ictus.125 Two of the guidelines this gives for patients with ictus or a transitory ischaemic accident include APS criteria: (a) anticoagulation has to be considered, given the risk of recurrence of thrombotic events and bleeding, and (b) when anticoagulation has not yet commenced, treatment with antiaggregants is indicated (LoE 4).

In the light of the results, it is not possible to confirm the efficacy of any specific therapy in patients with primary APS and arterial thrombosis. It has not been possible to prove that any significant differences exist between anti-aggregation and anticoagulation or between using high or standard doses of anticoagulation in the secondary prevention of arterial thrombosis.

As no primary studies which evaluate the efficacy of therapies in patients with primary APS and arterial thrombosis, we cannot extrapolate the results of the studies used as scientific evidence to the target population of our recommendations. Nevertheless, after reviewing the evidence the expert panel considers that in patients with APS defined by clinical and analytical criteria, and particularly those with other vascular risk factors or at high risk due to triple APA positivity, it would be possible to recommend standard range anticoagulation (INR 2–3). Finally, the preparatory group has also decided to issue a recommendation that association with anti-aggregation should be assessed in cases with more than one recurrence or poor anticoagulation control.

Primary antiphospholipid syndrome and recurrenceFor patients with thrombotic APS who suffer a recurrence in spite of conventional treatment, what should be the therapeutic attitude?

Recommendation:in refractory thrombotic APS it is recommended that conventional therapy be combined with anti-aggregant doses of acetylsalicylic acid, hydroxychloroquine or statins (grade D recommendation).

Recommendation:when oral anticoagulants are formally contraindicated it is recommended that low molecular weight heparin be used as the alternative therapy (grade D recommendation).

Recommendation:if arterial thrombosis recurs while receiving standard anticoagulation, the treatment may be optimised by adding anti-aggregation or increasing the anticoagulation dose (INR 3–4) (grade D recommendation).

Recommendation:in thrombotic APS that is refractory to conventional treatment it is recommended that cardiovascular risk factors be strictly controlled, while avoiding situations that predispose to new thrombotic events (grade D recommendation).

The conventional treatment of thrombotic APS is still based on anticoagulant treatment with VKA.100,126 Treatment with moderate intensity anticoagulation (INR from 2 to 3) reduces the risk of a new venous thrombotic episode, as well as probably new arterial episodes. In patients with an acute cerebrovascular accident, ASA at antiaggregant dose as well as moderate intensity anticoagulation have proven to be effective in preventing new events.74,100 However, and in spite of correct conventional treatment, a noteworthy percentage of patients with thrombotic APS develop new thrombotic episodes.127 At the current time treating these patients with refractory thrombotic APS is still controversial, and there are no well-designed studies which cover this clinical situation.

Although it has been suggested that increasing the intensity of anticoagulation (INR>3.0) may be an option in patients with refractory thrombotic APS, 2 RCT have shown this option to be ineffective and to give rise to a higher risk of haemorrhage.103,104 In spite of these studies, the intensity of anticoagulation in patients with arterial thrombotic events remains controversial.128,129 In any case, firstly it is necessary to check whether the thrombotic recurrence occurred in a sub-therapeutic range of INR before considering the event as refractory or not to anticoagulant therapy.130 A document prepared by experts recommends the use of treatment with LMWH as an alternative to conventional oral anticoagulation in patients with refractory thrombotic APS.74 This recommendation is solely based on series of patients with a limited number of treated individuals131,132 and on the acceptable safety profile of LMWH (LoE 3). The need for daily subcutaneous injection and considerations on the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (which is uncommon with LMWH), and especially the risk of osteoporosis after prolonged use are the main limitations of this therapeutic option.133 In patients with refractory thrombotic APS the possibility of adding an anti-aggregant dose of ASA to the treatment with oral anticoagulants has been suggested.127,134 Although the combination of both treatments may be more effective than monotherapy in preventing the recurrence of an acute cerebrovascular accident, it is also associated with a higher risk of bleeding.70,124 Although it has only been published as an abstract, a study performed in Japan has suggested the possible efficacy of dual anti-aggregation in patients with recurring arterial APS.135

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is an antimalarial agent which is known to have anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic properties in patients with SLE.136 Likewise, in experimental models of APS as well as in in vitro and in vivo studies HCQ has been shown to have antithrombotic capacity.133,136 Additionally, in a retrospective study HCQ was shown to be able to reduce levels of APA and the incidence of arterial thrombosis in patients with primary APS137 and to reduce the levels of APA in patients with SLE.138 In a non-randomised prospective study139 HCQ associated with oral anticoagulants was shown to be able to reduce the risk of venous thrombotic recurrence in comparison with anticoagulation in patients with primary APS.

Statins have many properties that may be of use in the prevention and treatment of patients with thrombosis.140 A recent study that included different groups of APA-positive patients showed that the association of fluvastatin significantly reduced the pro-inflammatory and prothrombotic biomarkers associated with the presence of APA.141

The use of biological therapy in patients with APS and refractory APS has been restricted to small series of patients and individual cases. In a review of the recent literature described how rituximab may be of use in some manifestations, such as haematological alterations, cutaneous involvement, cognitive deterioration or renal involvement, even though its exact role in thrombotic APS is still unclear.142,143 The use of eculizumab has been described anecdotally, and it is usually not included in the indications for refractory thrombotic APS. The possible use of intravenous immunoglobulin in patients with refractory thrombotic APS has also been suggested in small series of patients, although to date not correctly designed studies has demonstrated this.144,145

It is a well-known fact that traditional cardiovascular risk factors as well as certain prothrombotic situations (drugs, surgery and concomitant diseases, etc.) may play a fundamental role in the development of thrombosis in patients with APA and/or APS.134,146,147 Although there are no studies which properly evaluate the impact of a strict control of cardiovascular risk factors and/or suitable preventative measures in certain prothrombotic situations, it would seem reasonable to think that proper control in both clinical situations could contribute to a reduction of the risk of recurrence of thrombosis in patients with APS.126

New oral anticoagulantsWhat is the role of direct action oral anticoagulants (DOAC) in the treatment of patients with thrombotic APS?

Recommendation:direct action oral anticoagulants may be a good alternative in patients with venous thrombosis who are allergic to dicumarinic drugs and/or in case of difficulty in maintaining the INR in a therapeutic range with VKA (grade √ recommendation).

The anticoagulation agents of choice for patients with thrombotic APS are still the VKA, given the lack of randomised studies of the DOAC for these patients, and in spite of the use of these drugs in the treatment of thrombotic disease.72,148–151

The DOAC have a similar degree of efficacy to warfarin in the treatment of thromboembolic disease, and they are safer in terms of the appearance of haemorrhages. Although these drugs may be useful in the treatment of APS, recommendations have yet to be established for their use instead of VKA. This form of therapy is highly attractive as it requires no monitoring and has fewer interactions with other drugs or foodstuffs. Nevertheless, the results in patients with APS are still hardly conclusive.

There are 4 phase II/III clinical trials, of which 2 have offered data on patients with APS (EINSTEIN and RAPS)148,152 while 2 are still in recruitment phase150,153 (TRAPS and ASTRO-APS).

The aim of the phase III EINSTEIN-DVT study was to evaluate whether rivaroxaban is not inferior to enoxaparin/VKA in the treatment of acute symptomatic DVT without symptomatic pulmonary embolism and in the prevention of recurring venous thromboembolic events. Few patients with known thrombophilic disease were included (6.2%), and of these only 14% had APS. The incidence of events for the main variable of efficacy was low in comparison with the standard treatment of enoxaparin/VKA (0.9% vs 2.6%, respectively), although the size of the sample was so small that no data indicate that treatment with DOAC was more effective.148

The RAPS study is an open prospective RCT on non-inferiority in patients with APS and a history of venous thromboembolic disease. Its main aim is to prove that the intensity of anticoagulation achieved with rivaroxaban is not inferior to the intensity attained using warfarin, and it used the thrombin generation test for this purpose. 116 patients with APS and with or without SLE were included. They had suffered at least one thromboembolic event and had been in standard treatment with warfarin during at least 3 months after their last venous thromboembolic event. There were no differences between rivaroxaban and warfarin in the development of new thrombotic events or the risk of bleeding. Although rivaroxaban did not achieve the main study objective (in terms of its anticoagulant effect at an analytical level) in comparison with warfarin, the authors conclude that they consider it to be a safe and effective alternative treatment in patients with APS. This study also shows the need for more studies that evaluate the role of DOAC in patients who need more intense anticoagulation after recurring thrombotic events while receiving standard intensity anticoagulation, and in those with a history of arterial thrombosis.152

The TRAPS, which is in recruitment phase, compares rivaroxaban and warfarin in patients at high risk of recurrence, with APS and a history of arterial or venous thromboembolic events.150 ASTRO-APS is a pilot study that is under way, and it compares apixaban with VKA in secondary prevention.153

There are several other studies which took place in real clinical practice: observational studies, records and series of clinical cases. No recurring thromboembolic events, major bleeding or severe adverse effects occurred in the majority of these studies. In some cases the selection of patients may be distorted, as warfarin had failed beforehand. The authors consider DOAC to be a therapeutic alternative in patients with APS, especially those with poor control of their INR, while awaiting the results of the clinical trials and depending on patient thrombotic risk profile.154,155

These results indicate that the DOAC72,154,155 and especially rivaroxaban, which has already passed randomised phase III studies,148,152 are a good alternative to VKA. As these results show non-inferiority, the group of panellists considers them to be highly applicable in clinical practice, as they are safer than VKA and, in a few years time they may be in more general use for patients with poorly controlled venous thrombosis and/or allergy to dicumarinic drugs, as well as in those with monitoring difficulties or VKA resistance, always personalising the thrombotic risk profile in each case.

ConclusionsThis is the first official consensus of the Sociedad Española de Reumatología on the diagnosis and treatment of primary APS. Following an exhaustive review of the scientific evidence, and as there are few high quality studies, these recommendations are based fundamentally on systematic reviews, cohort studies and studies based on cases and control, as well as expert opinion.

21 recommendations have been prepared for the areas of diagnosis and evaluation; primary measures of thromboprophylaxis, together with the treatment of primary APS or secondary thromboprophylaxis. A treatment algorithm has been prepared on the basis of the recommendations, and this summarises the approach to treating APS (Fig. 1).

To establish the risk of thrombosis or obstetric complications, in everyday clinical practice it is now only necessary to simultaneously determine the APA which are included in the classification criteria. These are detected using ELISA techniques (aCL and AB2GPI) or by coagulometric tests (LA). The risk of presenting clinical manifestations of APS increases when LA has been detected, especially if all 3 APA (triple positivity) are detected in the same patient. Doctors must take into account that the determination of LA in anticoagulated patients is not as reliable as it is in untreated patients.

The need for prophylaxis in individuals who are carriers of APA without any associated clinical signs associated with APS is controversial. The panel of experts recommends using antiaggregant doses of ASA in carriers with a serological profile corresponding to risk, as well as those with cardiovascular risk factors and/or associated autoimmune disease (especially SLE). APA carriers, regardless of their risk profile, should be given prophylactic doses of LMWH during situations of high risk of thrombosis.

There are few good quality studies which would make it possible to determine which therapeutic option is the best for the thrombotic manifestations of APS. The panel of experts recommends starting treatment with unfractionated heparin or LMWH in case of a first episode of venous thrombosis, before continuing for an indefinite time with VKA in a therapeutic range for an INR of 2–3. There is even more controversy regarding arterial thrombotic manifestations, but the panel of experts recommends the same initial therapeutic attitude for venous thrombosis.

If in spite of standard treatment thrombotic manifestations recur, the panel of experts recommends the therapeutic options of associating ASA and/or HCQ, or increasing the range of INR to 3–4.

Regarding the use of DOAC in the treatment of APS, and due to the lack of available information now, this panel of experts recommends that they be used prudently in certain situations, such as APS with VKA allergy or intolerance, or in patients with venous thrombosis without good INR control with the usual therapy.

After the exhaustive review of the diagnosis and treatment of APS, it is clear that well-designed multicentre trials are required to classify patients, not only according to their different clinical manifestations, but also according to serological profile and the presence of comorbidities. This would make it possible to determine which therapeutic option is the best in each clinical situation. More studies are also needed to supply deeper knowledge about the pathogenesis of the disease, as well as new studies to clarify the role played by the APA which are not included in the classification criteria and their possible use in patients with the suspicion of APS but who fail to fulfil the criteria in force at the time.

These recommendations are based on the data now available, and they must be considered to be a decision-making aid for doctors directly involved in the care of patients with APS. Although these recommendations are considered to be decision-making tools for doctors, the decisions of doctors who are experts in APS must also be taken into consideration, as well as the shared opinion of the patient.

Research agendaAfter the systematic review of existing scientific evidence for the treatment of primary APS to prepare these recommendations, the panel of experts considered that many aspects should be included in the future research agenda, including the following:

Detection of antiphospholipid antibodies/new antiphospholipid antibodies- -

Studies are required which can add to knowledge of the pathogenic power of the APA included in primary APS classification criteria as well as those which are not.

- -

Studies should be undertaken to make it possible to agree on which techniques are the best for identifying the APA associated with the pathogenesis of thrombosis and morbidity during pregnancy.

- -

In vitro and in vivo studies are needed to identify the APA which are involved in the pathogenesis of APS, to aid the design of clinical trials in patients without clinical manifestations.

- -

Additional clinical trials are necessary with DOAC in different clinical situations, to confirm their efficacy and safety in APS.

- -

New tools or scores have to be developed which make it possible to identify the asymptomatic individuals who are APA carriers at risk of developing thrombotic phenomena and especially obstetric manifestations of the disease.

- -

Multicentre prospective studies are needed to make it possible to determine which primary prophylaxis is the most effective in asymptomatic carriers of APA, graded according to risk profile.

- -

Specific studies are necessary in patients with venous and arterial thrombosis that include patients with different risk profiles (triple positivity or the concomitant presence of other prothrombotic risk factors).

- -

Prospective studies are required to evaluate the possibility of suspending anticoagulation in patients with venous thrombosis at low risk of recurrence (no triple positivity, IgM isotypes or thrombosis coinciding with other risk situations such as taking contraceptives or undergoing surgery, etc.).

- -

Prospective studies are also needed to compare the efficacy of treating using isolated anticoagulation vs a combination with antiaggregation in patients with arterial thrombosis.

Fundación Española de Reumatología.

Conflict of interestsRafael Cáliz Cáliz has received financing from Abbvie, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, MSD, UCB and GSK to attend courses/conferences, and he has received fees from SER for talks and writing chapters of books.

Víctor Manuel Martínez Taboada has received financing from Abbvie, Menariniand and Pfizer to attend courses/conferences; he has received fees from Abbvie, MSD, Novartis, BMS and Roche for talks; financing from Servier for participating in research; economic aid from Roche to finance an independent research project, and economic aid from Servier and Hospira for consultancy for pharmaceutical companies or other technologies.

María Galindo has received financing from Pfizer, UCB, Lilly, Abbvie, Menarini and MSD to attend courses/conferences; fees from Rubió, Abbvie, MSD, UCB, BMS, Lilly and GSK for talks, and economic aid from GSK, Lilly, Celgene and UCB for consultancy for pharmaceutical companies or other technologies.

Francisco Javier López Longo has received financing from MSD, GSK, UCB and Pfizer to attend courses/conferences; fees from GSK and Roche for talks; financing from UCB and Roche for educational programmes or courses; financing from GSK for taking part in research, and economic aid from Sanofi-Aventis for consultancy for pharmaceutical companies or other technologies.

María Ángeles Martínez Zamora has no conflict of interests to declare.