Although non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (EspAax-nr) is well understood within health institutions, being considered along with radiographic EspAax (EspAax-r) as part of the same disease spectrum, patient understanding is unknown. The aim is to describe the patient's knowledge of the EspAax-nr entity.

MethodsAtlas 2017, promoted by the Spanish Federation of Spondylarthritis Associations (CEADE), aims to comprehensively understand the reality of EspAax patients from a holistic approach. A cross-sectional on-line survey of unselected patients with self-reported EspAax diagnosis from Spain was conducted. Participants were asked to report their diagnosis. Socio-demographic, disease characteristics and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) were compared between those patients self-reporting as EspAax-nr and EspAax-r.

Results634 EspAax patients participated. Mean age 45.7±10.9 years, 50.9% female and 36.1% university-educated. 35 (5.2%) self-reported as EspAax-nr. Compared to EspAax-r patients, those with EspAax-nr were more frequently women (48.6% vs 91.4%, p<0.001), had longer diagnostic delay (10.1±8.9 vs 8.5±7.6 years), higher psychological distress (GHQ-12: 7.5±4.9 vs 5.6±4.4) and similar degree of disease activity (BASDAI: 5.7±2.1 vs 5.7±2.0), and unemployment rates (20.0% vs 21.6%). 20.0% of EspAax-nr received biologics vs 36.9% of EspAax-r, p=0.043. Visits to the rheumatologist in the past year were similar in both groups (3.8±4.5 vs 3.2±3.8), while GP visits were much higher within EspAax-nr (8.0±10.7 vs 4.9±13.3 p=0.003).

ConclusionFor the first time, EspAax-nr characteristics and PROs have been analyzed from the patient's perspective. Both groups reported similar trends with the exception of EspAax-nr being more frequently women, younger, having longer diagnostic delay and lower use of biologic therapy.

Aunque se comprende bien la espondiloartritis axial no radiográfica (EspAax-nr) dentro de las instituciones sanitarias, se desconoce la comprensión del paciente cuando se considera conjuntamente con la espondiloartritis axial radiográfica (r-axSpA), como parte del mismo espectro de la enfermedad. El objetivo de este artículo es describir el conocimiento del paciente de la entidad EspAax-nr.

MétodosEl objetivo de Atlas 2017, promovido por la Federación Española de Asociaciones de Espondiloartritis (CEADE), es comprender la realidad de los pacientes con espondiloartritis axial (EspAax) desde un enfoque holístico. Se realizó una encuesta transversal online a pacientes españoles no seleccionados, con diagnóstico autoreportado de axSpA. Se solicitó a los participantes que informaran su diagnóstico. Se compararon las características sociodemográficas y los resultados reportados por el paciente (RPO) entre los pacientes que autoreportaron EspAax-nr y EspAax-r.

ResultadosParticiparon 634 pacientes de EspAax, con edad media de 45,7 ± 10,9 años, siendo mujeres el 50,9%, y un 36,1% con formación universitaria. Treinta y cinco de ellas (5,2%) autoreportaron EspAax-nr. En comparación con los pacientes de EspAax-r, aquellos con EspAax-nr eran mujeres con mayor frecuencia (48,6 vs. 91,4%, p < 0,001), tenían mayor demora en el diagnóstico (10,1 ± 8,9 vs. 8,5 ± 7,6 años), y mayor grado de angustia psicológica (12-item general health questionnaire [GHQ-12]: 7,5 ± 4,9 vs. 5,6 ± 4,4) y grado similar de actividad de la enfermedad (bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index [BASDAI]: 5,7 ± 2,1 vs. 5,7 ± 2), y tasas de desempleo (20 vs. 21,6%). El 20% de los pacientes de EspAax-nr recibían terapia biológica vs. el 36,9% de pacientes de r-axSpA, p = 0,043. Las visitas al reumatólogo el año anterior fueron similares en ambos grupos (3,8 ± 4,5 vs. 3,2 ± 3,8), mientras que las visitas al médico de atención primaria eran más frecuentes dentro del grupo de nr-axSpA (8 ± 10,7 vs. 4,9 ± 13,3 p = 0,003).

ConclusiónPor vez primera, se han analizado las características de EspAax-nr y PRO desde la perspectiva del paciente. Ambos grupos reportaron tendencias similares, exceptuando que el grupo de EspAax-nr estaba más frecuentemente formado por mujeres, más jóvenes, con mayor demora en el diagnóstico y menor uso de terapia biológica.

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that encompasses radiographic (r-axSpA, traditionally known as ankylosing spondylitis [AS]) and non-radiographic (nr-axSpA) forms. This inflammatory disease can lead to chronic pain, structural damage, and disability.1 In particular, physical restrictions and worsening quality of life caused by the disease are closely related to the limitations that patients face in their professional, social and family spheres.2,3

During the last decades, there has been a tremendous increase in the volume of research on axSpA. However, its non-radiographic form has been the focus of attention in the recent years. Unlike AS, which was first described around 1900,4 nr-axSpA was first described in the 1960s.5 As a silent form of axSpA that courses without structural damage in sacroiliac joints or the rest of the spine, nr-axSpA diagnosis has implied a recent challenge for Rheumatology. Up to date, no study has been able to report the incidence or prevalence rates of nr-axSpA.6

Since the appearance of MRI scan and its possibilities, there has been an overemphasis on radiological criteria in the diagnosis of spondyloarthritis.7 This has supported the advance in the research of the radiographic forms of axSpA at the expense of its non-radiographic forms. Either way, MRI by itself cannot serve as the touchstone to make a diagnosis of early axSpA due to limitations in both sensitivity and specificity, and because even an advanced imaging modality cannot capture the entire clinical spectrum of the condition.8

As a result, before the new Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) criteria, the previous classification criteria for SpA did not take into account the existence of non-radiographic forms, i.e. the 1984 Modified New York Criteria, the 1990 AMOR Criteria or the 1991 European Spondyloarthropaty Study Group criteria.9 It has not been until 2009 when the ASAS published new classification criteria to reliably classify axSpA in both its radiographic and non-radiographic forms,10 with solid sensibility and specificity (82.9% and 84.4% respectively).11 This is the first set of classification criteria that introduces nr-axSpA as a differentiated stage of the axSpA continuum.7

This way, it is not surprising that patients with r-axSpA and nr-axSpA experience a similar burden of disease, reporting similar levels of disease activity and functional limitation,12 mental health13 and overall level of quality of life.14 Research has also informed of substantial work impact on nr-axSpA patients, not significantly different from those of r-axSpA patients.15

The concept of nr-axSpA was coined a decade ago after the development of ASAS classification criteria for axSpA. After this period, nr-axSpA entity seems to be well understood and implemented within rheumatology and drug regulatory agencies. Nevertheless, the understanding and knowledge of nr-axSpA by patients is unknown as specific research on the subject is non-existent. The purpose of the present study is to describe the characteristics and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) of patients who self-reported as nr-axSpA and compare them to those who self-reported as r-axSpA, using data from the Spanish Atlas.

Materials and methodsWorking groupAtlas 2017 is an initiative of the Spanish Federation of Spondylarthritis Associations (CEADE), carried out by the Health & Territory Research (HTR) of the University of Seville and the Max Weber Institute, with the collaboration of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) and sponsored by Novartis Farmacéutica Spain.

Design and survey developmentA patient questionnaire was designed for individuals suffering from axSpA based on expert opinion of a panel of rheumatologists and patient research partners with axSpA. The questionnaire collected data regarding the following areas: diagnosis, treatment, comorbidity, employment, functional limitation and psychological health.

The interest of the Atlas was to collect a real-world sample, rather than relying on patients collected in clinical settings, a method that is subject to sampling bias as patients recruited this way are typically “good patients” with better treatment adherence and in close contact with the health system. For this reason, the distribution of the patient survey was done through CEADE, which forwarded it to local axSpA-specific patient organizations. Participating patients could send the survey to family and friends with the disease, using a non-probabilistic snowball sampling method.

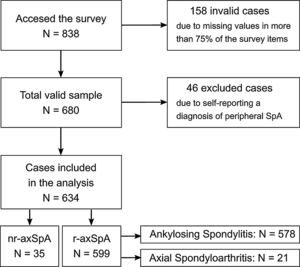

The online questionnaire surveying periods lasted from May 1 to August 15, 2016. After the validation and normalization of the information, the sample consisted of a total of 680 patients who responded to the majority of the questionnaire (completion rate was higher than 75%; see sample flow chart in Fig. 1). An extensive report of the Atlas 2017 method can be consulted for further information.16

Inclusion criteria were age of 18 years or older (adults), living in Spain during the survey and a self-reported diagnosis of axSpA. Diagnosis and type of condition was assessed by a multiple choice question at the beginning of the questionnaire which stated “Are you diagnosed with…?” followed by the following five options: “Ankylosing Spondylitis”, “Axial Spondyloarthritis”, “Non-radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis”, “Peripheral Spondyloarthritis” and “None of the above”. The selection of the latter option (“None of the above”) prevented the person from continuing to fill in the questionnaire and any data entered until that point was thus automatically discarded. For this study, patients who reported self-diagnosis of Peripheral Spondyloarthritis were removed from the sample. Two groups were considered, the r-axSpA group, comprised of those patients self-reporting diagnosis as either “Ankylosing Spondylitis” or “Axial Spondyloarthritis” and the nr-axSpA group, composed those declaring “Non-radiographic Axial Spondyloarthritis” as their diagnosis.

Supplementary indicesIn addition, a range of supplementary measures were collected in the questionnaire to assess specific areas:

- 1.

BASDAI (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index): A validated self-administered questionnaire assessing disease activity in patients with axSpA.17

- 2.

Spinal Stiffness Index: this index, based on the ASAS concept of spinal stiffness18 was developed specifically for this study, assesses the degree of stiffness experienced by patients in the spinal column, distinguishing between the cervical, dorsal, and lumbar areas. Possible responses range from least to most affected column (1: without stiffness, 2: mild stiffness, 3: moderate stiffness, and 4: severe stiffness), total scores are obtained by adding together the responses in each of the three areas of the spine without weighting resulting in a scale ranging from 3 to 12.

- 3.

Functional Limitation Index: this index, developed specifically for this study, assesses the degree of functional limitation in 18 daily life activities (dressing, bathing, showering, tying shoe laces, moving about the house, climbing stairs, getting out of bed, using the bathroom, shopping, preparing meals, eating, household cleaning, walking down the street, using public transportation, driving, going to the doctor, doing physical exercise, having sex). The activities were selected and validated by the scientific committee of the Atlas taking into account the opinion of patient research partners. Each of these 18 daily life activities was assigned as 0 for no limitation, 1 low limitation, 2 medium limitation and 3 high limitations, resulting in values between 0 and 54. A total score from 0 and 18 was considered low limitation, between 18 and 36 medium limitation and between 36 and 54 high limitation.

- 4.

GHQ-12 (General Health Questionnaire–12): This questionnaire evaluates psychological distress using 12 items. For the present study, these were transformed into a dichotomous score (0-0-1-1), called the GHQ score. The cut-off point of 3 implied those with a score of 3 or more may be experiencing psychological distress.19

For the analyses, nr-axSpA group was compared with a r-axSpA group, combining the data from the AS and axSpA conditions (Fig. 1). Sociodemographic, disease-related, employment status, healthcare utilization and treatment variables were compared between groups patients using Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis and Chi-square tests to assess the statistical significance of the observed differences between both groups.

ResultsA total of 680 people participated in the Atlas 2017 survey of which 46 participants who self-reported Peripheral axSpA were discarded, resulting in 634 being included in this study. For this sample of 634 participants, mean age was 45.7±10.9 years, 50.9% were female and 36.1% university-educated. 35 (5.5%) self-reported a diagnosis of nr-axSpA while the remaining 599 (94.5%) were classified as r-axSpA as they self-reported either AS (96.5%) or axSpA (3.5%). The vast majority of patients with self-reported nr-axSpA were women (91.4%), compared to 48.6% of women across patients with self-reported r-axSpA (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics and patient-reported outcomes of patients with self-reported nr-axSpA (N: 35, unless other specified) and r-axSpA (N: 599, unless other specified).

| Variable | Self-reportednr-axSpA (N: 35)mean±SD or n(%) | Self-reportedr-axSpA (N: 599)mean±SD or n(%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.1±8.8 | 46.0±10.9 | 0.045* |

| Gender (female) | 32 (91.4) | 291 (48.6) | <0.001*** |

| Education level (university) | 17 (48.6) | 212 (35.4) | 0.351 |

| Marital status (married) | 20 (57.1) | 434 (72.5) | 0.223 |

| Disease duration | 14.1±10.1N: 18 | 21.8±12.1N: 486 | <0.001*** |

| HLA B27 | 20 (64.5)N: 31 | 350 (75.9)N: 461 | 0.155 |

| BASDAI (0–10) | 5.7±2.1N: 18 | 5.7±2.0N: 368 | 0.792 |

| High BASDAI (≥4) | 15 (83.3)N: 18 | 294 (79.9)N: 368 | 0.721 |

| Spinal Stiffness Index (3–12) | 6.5±2.5N: 24 | 7.5±2.7N: 437 | 0.053 |

| Functional Limitation Index (0–54) | 45.6±10.4 | 42.1±10.0N: 531 | 0.007** |

| GHQ-12 (0-12) | 7.5±4.9N: 20 | 5.6±4.4N: 418 | 0.087 |

| Anxiety diagnosis | 6 (17.1) | 116 (19.4) | 0.746 |

| Depression diagnosis | 5 (14.3) | 86 (14.4) | 0.991 |

| Fibromyalgia | 4 (11.4) | 44 (7.3) | 0.375 |

| Diagnostic delay (years) | 10.1±8.9N: 32 | 8.5±7.6N: 482 | 0.193 |

Of the people with self-reported r-axSpA and nr-axSpA who completed the BASDAI scale the average score was exactly the same (5.7) which implies that the average disease activity was high (exceeding 4 which is the cut-off point indicating high disease activity score, according to rheumatologic standards) for both groups. The mean diagnostic delay declared by people with self-reported nr-axSpA was more than a year and a half longer than among those with self-reported r-axSpA (10.1 compared to 8.5). Patients with self-reported nr-axSpA showed higher levels of psychological distress, averaging at 7.5 at the GHQ-12 score whereas patients with other forms of self-reported r-axSpA averaged 5.6 (Table 1).

Distribution of self-reported r-axSpA and nr-axSpA patients regarding active and inactive population was equivalent, with similar unemployment rates. Out of the inactive population, two thirds of patients with self-reported nr-axSpA were on temporary sick leave at the moment of the survey compared to one quarter of patients with self-reported r-axSpA (Table 2).

Employment status of patients with self-reported nr-axSpA (N: 35) and r-axSpA (N: 599).

| Employment status | Self-reportednr-axSpA (N: 35)mean±SD or n(%) | Self-reportedr-axSpA (N: 599)mean±SD or n(%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active | 20 (57.1) | 370 (64.5) | |

| Employed | 16 (80.0) | 290 (78.4) | 0.864 |

| Unemployed | 4 (20.0) | 80 (21.6) | |

| Inactive | 15 (42.9) | 204 (35.5) | |

| Temporary sick leave | 10 (66.6) | 47 (23.0) | 0.006** |

| Permanent sick leave | 3 (20.0) | 55 (27.0) | |

| Retired | 0 (0.0) | 59 (28.9) | |

| Early retired | 0 (0.0) | 9 (4.4) | |

| Homemaker | 1 (6.7) | 26 (12.7) | |

| Student | 1 (6.7) | 8 (3.9) |

*The association is significant at the 0.05 level.

**The association is significant at the 0.01 level.

***The association is significant at the 0.001 level.

Patients with self-reported nr-axSpA reported equivalent distributions regarding their disease-related appointments to healthcare specialists in the year prior to the survey with few exceptions. Patients with nr-axSpA reported a greated frequency of visits to orthopedic specialist and general practitioner, more than double to the physiotherapist and almost triple to the gastroenterologist (Table 3). Regarding the number of medical test taken by patients with self-reported nr-axSpA, similar frequencies were reported along both self-reported nr-axSpA and r-axSpA patients (Table 4).

Specialists appointments in the past 12 months of patients with self-reported nr-axSpA (N: 35) and r-axSpA (N: 599).

| SpecialistAppointments | Self-reportednr-axSpA (N: 35)mean±SD or n(%) | Self-reportedr-axSpA (N: 599)mean±SD or n(%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatologist | 3.8±4.5 | 3.2±3.8 | 0.377 |

| General practitioner | 8.0±10.7 | 4.9±13.3 | 0.003** |

| Clinical nurse | 2.0±4.3 | 2.1±8.4 | 0.873 |

| Orthopedic specialist | 0.9±2.0 | 0.5±2.0 | 0.003** |

| Physiotherapist | 14.3±28.3 | 6.4±19.0 | 0.012* |

| Ophthalmologist | 1.0±1.8 | 0.8±2.2 | 0.135 |

| Pulmonologist | 0.2±0.6 | 0.2±0.8 | 0.462 |

| Cardiologist | 0.2±1.0 | 0.2±0.8 | 0.574 |

| Psychologist | 1.4±3.3 | 2.0±9.9 | 0.034* |

| Gastroenterologist | 0.142±0.4 | 0.058±0.5 | 0.002** |

Medical test undertaken before diagnosis of patients with self-reported nr-axSpA (N: 35) and r-axSpA (N: 599).

| Medical test | Self-reportednr-axSpA (N: 35)mean±SD or n(%) | Self-reportedr-axSpA (N: 599)mean±SD or n(%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-rays | 3.8±4.5 | 3.2±3.8 | 0.377 |

| MRI | 1.7±2.5 | 0.6±1.4 | <0.001*** |

| Ultrasound scan | 0.4±0.7 | 0.3±0.8 | 0.051 |

| Radionuclide scintigraphy | 0.2±0.5 | 0.1±0.4 | 0.014* |

| CT scan | 0.03±0.2 | 0.04±0.3 | 0.911 |

| Blood test | 3.8±5.4 | 3.1±3.8 | 0.947 |

| Urine test | 1.9±2.8 | 1.9±2.9 | 0.794 |

With regard to pharmacologic treatments administered to patients, similar NSAID and DMARD usage rates were reported for both groups (r-axSpA and nr-axSpA). With respect to biologic treatment, there were differences, as more than a third of self-reported r-axSpA patients declared to be taking biologics as opposed to the fifth of self-reported nr-axSpA patients that declared to be taking biologics (Table 5).

Pharmacological treatment undertaken in the past 12 months of patients with self-reported nr-axSpA (N: 35, unless other specified) and r-axSpA (N: 599, unless other specified).

There is a discussion whether nr-axSpA and r-axSpA are different clinical entities or different stages of the same disease.20 The fact that most of the studies report about 10–40% of patients with nr-axSpA to progress to r-axSpA over a period of two to ten years,21 and that both entities share similar disease characteristics incline researchers towards the approach of being part of the same disease spectrum. According to published data, radiographic and non-radiographic forms of spondyloarthritis mainly differ in presence of substantial sacroiliac joints damage in r-axSpA forms and a higher proportion of females, young patients and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) serum levels among nr-axSpA forms.22 However, r-axSpA and nr-axSpA seem to have more aspects in common than differentials. Research from several cohorts such as the DESIR23 or SPACE24 have found similarities between both groups regarding symptom duration, age at onset of first symptoms, prevalence of HLA-B27 carriership,25 patient-reported outcomes, and the presence of extra-articular or peripheral manifestations.26,27 They also share a common course, as there are similarities in their disease development. As found out by the GESPIC cohort, both nr-axSpA and r-axSpA share factors associated to radiographic progression such as presence of syndesmophites and acute phase reactants.28 However, most of these previous data with regard to nr-axSpA comes from studies conducted in central or northern Europe and focused on the clinical aspects of the disease.

The Atlas places its focus of interest on Spain, a country in the Mediterranean zone, with a representative sample of the different Autonomous Communities and not only exploring clinical data but also considering functional limitation in daily life, work life and mental health from patient's perspective. In this study, nr-axSpA account for only about 5% of all axSpA. One possible factor that could explain this low percentage is that the recruitment was done through the national patient organization (CEADE) and therefore, it is not possible to infer any consideration regarding the prevalence of nr-axSpA in relation to that of axSpA. Additionally, women comprised a substantial percentage of the sample, which is common in studies conducted through online surveys.29

In spite of this, results of the present study including self-reported nr-axSpA and r-axSpA patients are consistent with published data collected directly in clinical settings. Patients with self-reported nr-axSpA informed of trends similar to that of patients with r-axSpA in the following aspects explored: sociodemographic, employment, healthcare utilization, disease activity, spinal stiffness and pharmacological treatments. Regarding socio-demographic, disease characteristics and PROs, the only significant observed differences were that, compared with patients with r-axSpA, those with nr-axSpA had a higher proportion of females, greater functional limitation in daily life activities and were more frequently on temporary sick leave. In addition, a trend toward a longer diagnostic delay and worst mental health status in patients with nr-axSpA was also observed. We examined whether the presence of fibromyalgia could have affected PROs or diagnostic delay. However, it is unlikely that the presence of fibromyalgia could have altered our results because the percentage of fibromyalgia reported was within the published values of axSpA30,31 and, additionally, there were no statistically significant differences in the distribution of fibromyalgia between the two groups.

Results of this Spanish Atlas survey are aligned with those of previous studies like that of the GESPIC cohort, in which, of all aspects assessed between radiographic and no-radiographic forms of axSpA, only a difference in gender ratios was found (women were more likely than men to have a diagnosis of nr-axSpA).22 Another study, also carried out in Germany in a sample of 100 patients (44% of them with a non-radiographic diagnosis) concluded that even if nr-axSpA and axSpA patients differed in signs of inflammation, they showed no differences regarding health status and disease activity. The same study also reported a higher prevalence of nr-axSpA in women.12 On the other hand, patients with nr-axSpA in the Atlas reported higher functional limitation in daily activities. These results differ with data from other populations such as SPACE or DESIR, in which no differences between groups were found for functional limitation. This may be explained by the different instrument employed to assess this outcome and also by the difficulties of patients with shorter disease duration to cope with the disease, as in our study the nr-axSpA group had a significantly shorter disease duration compared to that of SPACE and DESIR. In addition, patients with nr-axSpA reported to be on temporary sick leave more frequently than patients with r-axSpA. Similarly, to functional limitation, this could also be related to the difficulties to cope with the disease, as they are younger and so entering the labour market. Furthermore, in our study patients with self-reported nr-axSpA declared a higher level of psychological stress than their radiographic counterparts. However, sample size for that comparison was particularly low in the case of self-reported nr-axSpA so statistical results may be subject to sample bias, and can compromise the conclusions drawn from these results. In any case, other studies that have assessed psychological burden have not found statically significant differences between nr-axSpA and axSpA groups.26

Another aspect standing out in patients with self-reported nr-axSpA is a tendency for longer diagnostic delay with respect to those with self-reported r-axSpA, probably related to the absence of evidence of radiographic damage. Paradoxically, if we assume that some of the non-radiographic patients’ progress to a radiographic stage, for sure a number of r-axSpA patients were only diagnosed at the beginning of their radiographic stage. This means that current r-axSpA patients could have go through a previous non-radiographic phase that was at the time totally unknown to rheumatologists and was, therefore, ignored and deprived of an early diagnosis and treatment.

As for the medical test used for diagnosis, both groups followed a similar diagnostic pathway with the exception of MRI scan, more frequently used in the nr-axSpA group. This is understandable as the rheumatologist, with the support of the radiologist, would probably run various scans in order to really determine whether or not there was radiographic damage. Statistically significant differences also arise for the radionuclide scintigraphy option, although the frequency of use of this medical test is too low for drawing conclusions on a sample this size.

Regarding healthcare utilization, both groups reported similar profiles. However, the group self-reporting as nr-axSpA declared to visit general practitioners, orthopedic specialists and physiotherapists more frequently than their counterparts. This need to visit more medical specialists could be due to poorer disease outcomes. On the other hand, nr-axSpA patients reported less visits to psychologist/psychiatrist in the year prior to the survey, despite declaring greater psychological distress. This would point to an unmet need for psychological support for this group of patients.

Other important idea suggested by the data collected is that, despite self-reported nr-axSpA patients have similar levels of disease activity and spinal stiffness than r-axSpA patients, they are not receiving biologic treatments at an equivalent rate.

LimitationsHowever, this study has some limitations. First, all data of the survey was self-reported, and did not attempt to confirm participant diagnosis nor to support participant responses with clinician reported assessments. As such, clinical data such as the BASDAI or GHQ-12 scores, as well as the report of extra-articular manifestations may suffer from response bias. Nevertheless, the sample characteristics were consistent with previous cohorts including patients with confirmed axSpA and nr-axSpA,12,14,22,25,32 and as the aim of the survey was to better understand the patient perspective, direct feedback was preferred. Secondly, as the sample was unselected there was no means to ensure the size of the nr-axSpA subgroup. The final sample had in total 35 patients with self-reported nr-axSpA, which precluded the possibilities of the inferential analysis. Low sample size of the nr-axSpA group could be due to either misdiagnosis or patient misunderstanding of the disease, although women, well-represented in the sample, are more likely to be knowledgeable about their health status. Still, the descriptive analysis supports the goal of our study: to check the health and disease status of a neglected population of nr-axSpA patients.

ConclusionFor the first time, nr-axSpA disease characteristics and PROs, as well as patients’ journey towards diagnosis, healthcare and treatments have been analysed from the patient's perspective. Results show a high burden of disease of nr-axSpA patients, comparable to that of the r-axSpA group, with similar work impact and use of healthcare resources, suggesting that both nr-axSpA and r-axSpA are associated to an equivalent level of suffering. Nr-axSpA patients reported the same level of disease activity, and similar levels of spinal stiffness, compared to r-axSpA patients, even if they are not receiving the same rate of biologics treatments.

Further research is needed on clinical aspects and impact on daily life aspects for a better understanding of the patient experience with the condition and the improvement of their healthcare, management and quality of life.

Authors’ contributionsM. Garrido-Cumbrera made substantial contributions to study conception and design and to the interpretation of the data. He contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the last version to be published.

J. Gratacos made substantial contributions to study conception and design and to the interpretation of the data. He contributed to the writing of the manuscript and aproved the last version to be published.

E. Collantes-Estevez made substantial contributions to study conception and design and to the interpretation of the data. He contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the last version to be published.

P. Zarco made substantial contributions to study conception and design and to the interpretation of the data. He contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the last version to be published.

C. Sastre made substantial contributions to study conception and design and to the interpretation of the data. He contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the last version to be published.

S. Sanz-Gómez made substantial contributions to study conception and design and to the interpretation of the data. He contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the last version to be published.

V. Navarro-Compán made substantial contributions to study conception and design and to the interpretation of the data. She contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the last version to be published.

FundingThe Atlas 2017 study was supported by Novartis Farmacéutica Spain, which in no mean affected the analysis or interpretation of results.

Conflict of interestDr. Jordi Gratacós has received unrelated honoraria or research grants from Abbvie, BMS, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB.

Dr. Eduardo Collantes-Estévez has received unrelated honoraria or research grants from Abbvie, BMS, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB.

Mr. Carlos Sastre is an employee of Novartis Farmacéutica Spain.

Dr. Victoria Navarro-Compán has received unrelated honoraria or research grants from Abbvie, BMS, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB.

The rest of the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Mr. José Correa-Fernández, from Health and Territory Research (HTR), Universidad de Sevilla, carried out the data analysis.