Halitosis is a common reason for consulting a physician that entails a broad differential diagnosis, as it can be a manifestation of extraoral or systemic diseases, like the case of Sjögren's syndrome (SS) that we present here.

The patient was a 36-year-old woman, with nothing remarkable in her medical or surgical history, who was referred from primary care with a 1-year history of persistent halitosis. She had been examined by dentists and had her teeth cleaned several times, but there was no evidence of oral disease to explain her condition. She had been studied in the ear, nose and throat and the gastroenterology departments, and had undergone computed tomography of the sinuses, rhinoscopy, upper gastrointestinal series, breath test and laboratory analyses, none of which had revealed signs of disease. She had tried mouthwashes, proton pump inhibitors, prokinetic agents and over-the-counter products, but the halitosis persisted, limiting her quality of life. In internal medicine, she reported having halitosis every day. It improved on eating and with chewing gum. She needed to drink water constantly, even at night, and had a feeling of dry mouth and frequent ocular discomfort, with pruritus, that she attributed to her job and stress. She had no complaints associated with organs or apparatuses. Physical examination only revealed evident halitosis when she exhaled through the mouth and dry tongue; the rest of the oral cavity was normal. The results of laboratory analyses with a complete blood count, tests for hemostasis, and kidney and liver function tests were normal. Indirect immunofluorescence only revealed an antinuclear antibody titer of 1/160 with a homogeneous pattern and the presence of anti-Ro. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasound were normal (Table 1, available in online supplementary material). The Schirmer test in both eyes resulted in moisture of less than 5mm in 5min, and the score with rose Bengal staining was 4 points. As the patient refused to undergo salivary gland biopsy, gamma scintigraphy of parotid glands was performed. It revealed a grade II/IV bilateral diffuse uptake deficit. On the basis of the results obtained, a diagnosis of halitosis secondary to xerostomia associated with SS was established. The recommendations were that she eliminate caffeine consumption and use sugarless mint or lemon-flavored candy and alcohol-free mouthwashes. Frequent hydration was also indicated, as was the use of artificial tears and saliva. As the patient perceived a partial improvement in dry mouth and halitosis, treatment with pilocarpine was initiated, with incremental doses up to 5mg/6h, at which point, satisfactory symptom control was achieved. Progressive improvement in dry mouth and halitosis were observed in office visits and there have been no complications during follow-up.

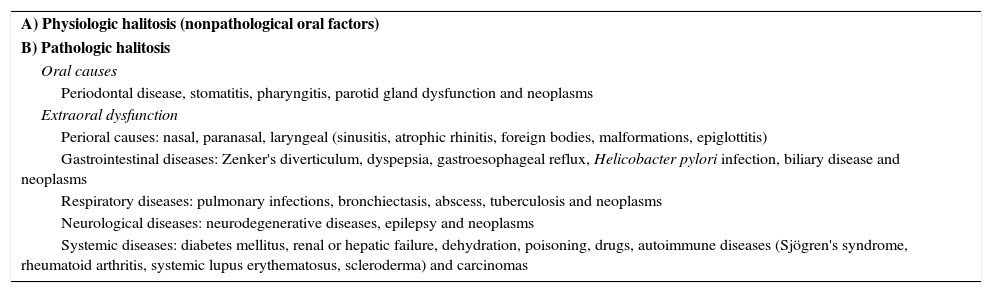

Differential Diagnosis of True Halitosis.

| A) Physiologic halitosis (nonpathological oral factors) |

| B) Pathologic halitosis |

| Oral causes |

| Periodontal disease, stomatitis, pharyngitis, parotid gland dysfunction and neoplasms |

| Extraoral dysfunction |

| Perioral causes: nasal, paranasal, laryngeal (sinusitis, atrophic rhinitis, foreign bodies, malformations, epiglottitis) |

| Gastrointestinal diseases: Zenker's diverticulum, dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux, Helicobacter pylori infection, biliary disease and neoplasms |

| Respiratory diseases: pulmonary infections, bronchiectasis, abscess, tuberculosis and neoplasms |

| Neurological diseases: neurodegenerative diseases, epilepsy and neoplasms |

| Systemic diseases: diabetes mellitus, renal or hepatic failure, dehydration, poisoning, drugs, autoimmune diseases (Sjögren's syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma) and carcinomas |

Halitosis is defined as an unpleasant odor in the exhaled breath, which can result in an important social problem, and may be the consequence mainly of dental disease.1 In some cases, it is associated with extraoral disease (ear, nose and throat, gastrointestinal, hepatic, neurological, respiratory or systemic), which may require specific treatment and follow-up.2 Sjögren's syndrome is a chronic autoimmune disease in which there is a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in the exocrine glands and in certain extraglandular tissues. It causes a progressive destruction of the latter, producing xerostomia and xerophthalmia, among other symptoms.3 Saliva is composed of water, electrolytes, proteins, glycoproteins, defensins, proteases, histatins and lysozymes, as well as other molecules with biological and biochemical properties that are essential in the maintenance of the oral physiology.

Xerostomia is among the classification criteria of the disease, and is the complaint most widely reported by patients, among other oral problems caused by the reduced salivary flow. Our patient met 5 of the 6 American-European criteria established in 2002.4,5 The microbiological composition of the saliva plays an essential role since, in patients with reduced salivary flow, as in SS, there is a modification in the bacterial flora. This circumstance is related to an increase in the concentration of microorganisms like Lactobacillus acidophilus, Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans, among others, which favors the development of caries, infections (candidiasis), burning mouth syndrome, glossodynia, dysphagia, halitosis and oral lesions.6,7 Halitosis is a result of this reduced salivary flow. However, it is rarely mentioned as a major manifestation leading to the perception and suspicion of a diagnosis of SS, as occurred in our patient.6 The treatment consists of multiple hygienic and dietary measures that favor oral hydration, the use of artificial saliva and, in the most severe cases, systemic therapy, for example, with cholinergic agents.8,9

Please cite this article as: Ruiz Serrato A, Infantes Ramos R, Jiménez Ríos A, Luján Godoy PP. Síndrome de Sjögren y halitosis: descripción de un caso clínico. Reumatol Clin. 2016;12:298–299.