Sarcoidosis is chronic non-caseifying granulomatous disease that is multisystemic and idiopathic.1,2 Löfgren’s syndrome (LS) is an acute grade I form of sarcoidosis which evolves benignly and without sequelae in 95% of cases.3,4 It gives rise to stereotyped clinical findings: erythema nodosum (EN), bilateral hilar lymphadenopathies, involvement of the joints and fever (the classic triad).3,4 We present the case of a patient who debuted with classic LS.

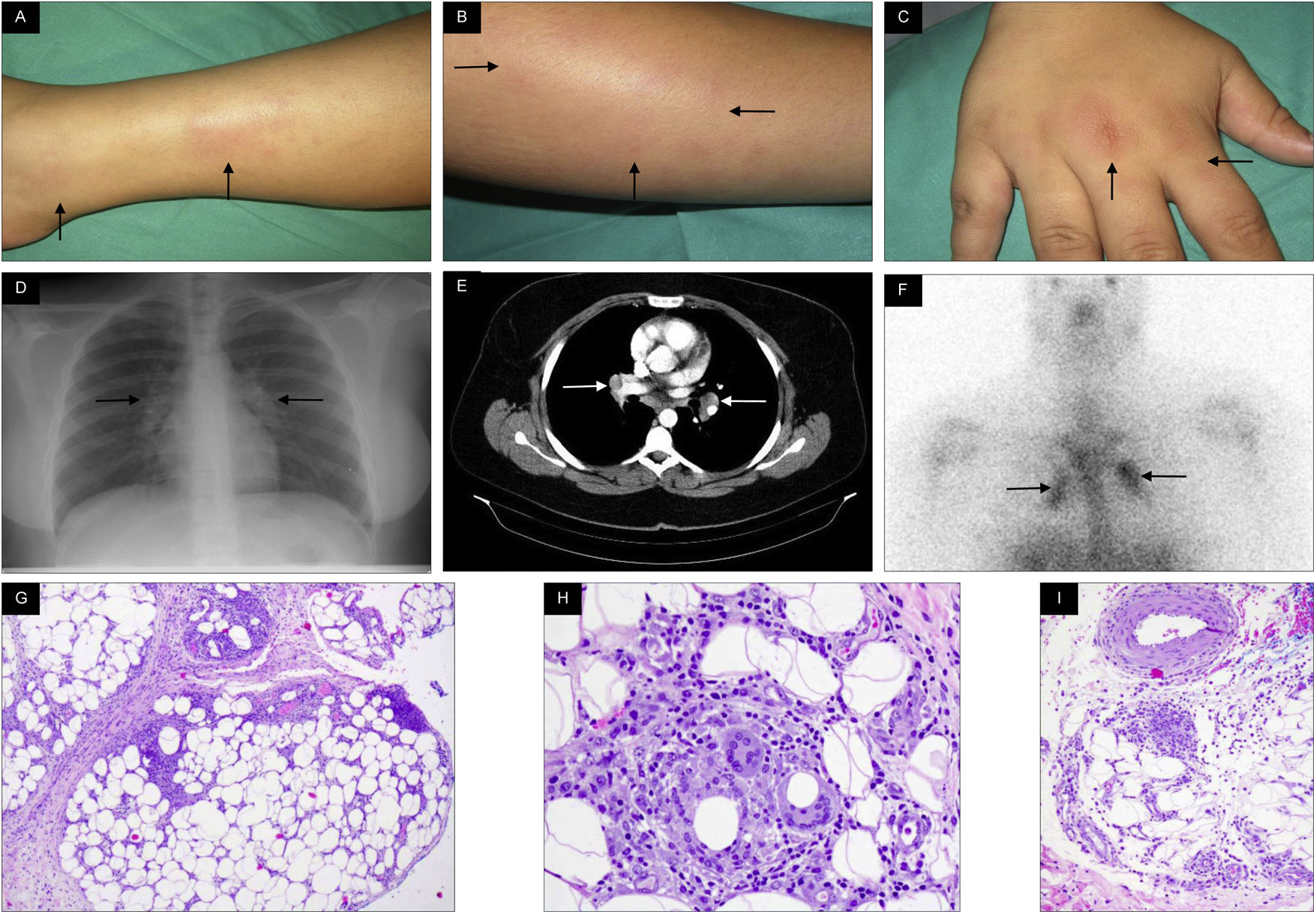

A woman in the third decade of life, Caucasian, an active smoker with a BMI of 34 and subclinical hypothyroidism, without other noteworthy medical factors. She was admitted due to symptoms that had evolved over 4 weeks, of asthenia, 38 °C fever and cutaneous bilateral pretibial and forearm lesions (Fig. 1Aand B) that are clinically indicative of EN: erythematous papules, indurate, painful and not pruriginous, as well as pain and tumefaction in both ankles, knees and hands, indicative of periarthritis (Fig. 1C). The rest of the physical examination was normal. In blood analysis the erythrocyte sedimentation rate in the first hour of 78 mm stood out, with 13,000/mm3 leucocytosis. Viral and bacterial serology was performed, together with ACE, autoantibodies, calciuria, blood and Mantoux cultures, all of which were negative. Thoracic x-ray (Fig. 1D) showed bilateral hilar lymphadenopathies, corroborated by high resolution thoracic CT imaging (Fig. 1E) and gammagraphy using gallium-67 (Fig. 1F), with a normal pulmonary parenchyma. Biopsy of a skin lesion showed predominantly septal histiocytic inflammatory infiltrate, without necrosis or vasculitis, with negative Ziehl-Neelsen staining, compatible with EN (Fig. 1G, H and I). Bronchoscopy, respiratory function tests, eye fundus and the bone x-ray series were normal. The Ziehl-Neelsen staining and Löwenstein–Jensen bronchoaspirate culture from the bronchoscopy were negative. LS was diagnosed by exclusion and clinical-radiological means. Treatment with 40 mg oral prednisone commenced (in decreasing doses), with a favourable evolution after 12 and 24 weeks of clinical, radiological and respiratory function follow-up.

(A and B) Skin lesions in the form of erythematous indurate papules at pretibial level on the right leg and left forearm, respectively, indicative of erythema nodosum. (C) Tumefaction of the right hand, indicative of periarthritis. (D, E and F) Simple x-ray of the thorax, CT image of the thorax and gallium-67 gammagraphy showing bilateral hilar lymphadenopathies. (G, H and I) Histopathology of a skin lesion showing predominantly septal histiocytic inflammatory infiltrate, without necrosis or vasculitis.

Transbronchial biopsy is indicated in all probable cases of sarcoidosis, except for those with classic LS (only in the case of unilateral hilar or isolated right paratracheal lymphadenopathies).1–4 Nevertheless, several entities should be considered in the differential diagnosis with LS or stage I sarcoidosis (Hodgkin’s lymphoma, tuberculous lymphadenitis, Whipple’s disease, yersiniosis, brucelosis, syphilis and the initial phase of HIV), which were all reasonably excluded in our case. On the other hand, the diagnosis of EN is clinical, and skin biopsy is indicated in certain cases (persistent symptoms, atypical location, ulceration, the suspicion of infection by Mycobacterium or leukocytoclastic vasculitis).1–4 In our case this was not indispensable. Although up to two thirds of cases may remit spontaneously, steroid therapy for LS is the first line of treatment.1,2 It should be underlined that a response to treatment does not necessarily confirm the diagnosis of sarcoidosis; an exhaustive follow-up is therefore essential, re-evaluating the case and ruling out other diseases in the case of resistance or relapse. It is also necessary to take into account non-adherence, inappropriate doses or progression of the disease. Likewise, measurement of ACE levels in serum is not very sensitive, and nor is it specific as a diagnostic test or a therapeutic guide.1,2

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.