Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) primarily affects the upper limbs and can cause disturbances in the performance of daily activities. The main objective of this study was to establish the relationship between self-efficacy, pain intensity, and duration of symptoms in patients with RA and analyse how each influences functional disability, and to determine the predictive value of self-efficacy over the other variables.

MethodsCross-sectional study with a sample of 117 women diagnosed with RA. The endpoints were the visual analogue scale (VAS), Quick-DASH questionnaire and the Spanish scale of self-efficacy in rheumatic diseases.

ResultsThe most significant model for function (R2 = 0.35) includes function and pain, therefore, there is a relationship between self-efficacy, pain intensity, and upper limb functionality.

Discussion and conclusionsOur results agree with previous studies where a relationship between self-efficacy and functional disability is established, as well as self-efficacy and its relationship with physical functions, demonstrating that a low level of self-efficacy implies a decrease in functionality; however, no variable is more predictive than another.

La artritis reumatoide (AR) cursa generalmente con una afectación mayor en el miembro superior, pudiendo ocasionar afectación en el desempeño de actividades en el día a día. El objetivo principal de este estudio fue establecer la relación entre la autoeficacia, la intensidad del dolor y la duración de los síntomas en pacientes con AR, y analizar cómo y en qué medida cada uno de ellos influye en la discapacidad funcional, así como, conocer el valor predictivo de la autoeficacia sobre las demás variables.

MétodosEstudio transversal con una muestra de 117 mujeres con AR. Las variables de evaluación empleadas fueron la escala visual analógica (EVA), el cuestionario QuickDASH y la escala española de autoeficacia en enfermedades reumáticas.

ResultadosLos resultados muestran que el modelo más significativo para la función (R2 = 0,35) incluye la variable función y dolor, por lo que, sí hay relación existente entre la autoeficacia, la intensidad del dolor y la funcionalidad del miembro superior, así como la asociación de las puntuaciones obtenidas en la EVA, QuickDASH y la escala española de autoeficacia en enfermedades reumáticas para su evaluación.

Discusión y conclusionesNuestros resultados, concuerdan con estudios previos donde se establece la posible relación entre la autoeficacia y la discapacidad funcional, así como la autoeficacia y su relación con funciones físicas, demostrando que un bajo nivel de autoeficacia implica una disminución de la funcionalidad, pero sin que ninguna variable sea más predictora que otra.

Rheumatic diseases (RD) generally affect the upper limb, especially the hands, and can cause deformity or swelling followed by pain and functional limitation, affecting the patient’s performance of daily activities, lifestyle and, therefore, motivation and general satisfaction.1–3 Therefore, the assessment of functional disability in the hand with rheumatic diseases should be carried out through the performance of activities covering all occupational areas,4 and taking into account factors such as self-efficacy or pain intensity. Self-efficacy expectations refer to the belief in one’s own capabilities, and arise when performing certain behaviours to successfully achieve a goal,5 such as pain management6 or occupational performance.7 Self-efficacy is a component that can determine a person's effort or involvement in the achievement of goals, and a person with a high level of self-efficacy is one who makes more effort and is more involved.8 Previous studies have shown that there is a low level of self-efficacy in people suffering from rheumatic diseases,9 and that if self-efficacy is increased, functionality will improve by up to 28%.10 Pain is considered one of the most relevant symptoms in rheumatic diseases, and can become a barrier to carrying out occupations independently.11 The perception of self-efficacy has also been associated with a better state of health in diseases with chronic pain, even being a predictive value in the general state of health in patients with fibromyalgia.12

In rheumatic diseases, the duration of symptoms is proportional to the accumulated damage due to the progression of symptoms and the passage of time.13,14 It is important to consider self-efficacy, symptom duration and pain as a set of interrelated factors that can directly influence the patient with rheumatic disease, the performance of daily activities and possible functional disability of the upper limb. Previous research shows that self-efficacy is related to functional disability of the upper limb15 and emotional state, highlighting that the greater the self-efficacy, the less the pain and the better the occupational performance in adults,11 but we do not know to what extent this correlation holds in people diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Thus, the main objective of this study is to investigate the relationship between self-efficacy, pain and function, as well as the predictive capacity of self-efficacy, measured with the Spanish scale of self-efficacy in rheumatic diseases, with respect to pain intensity, symptom duration and functional disability of the upper limb measured with the Spanish version of the QuickDASH questionnaire in patients with RA.

Material and methodsStudy designProspective observational multicentre study involving the Department of Occupational Therapy (OT) of the centre of the Asociación de Artritis Reumatoide y Espondilitis de Móstoles, Madrid and the Centro Tecan, Clínica de la Mano, Málaga, located in Málaga. All participants signed an informed consent form and the procedure was carried out following the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki.16 The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee with the number 16-2022-H.

ParticipantsWomen over 18 diagnosed with RA and referred to the OT Department who agreed to participate in the study. Participants were included if they presented limitations in the functionality of the upper limb and pain above 4 out of 10 during daily activities, who were able to read and had the ability to understand, and autonomy to complete the questionnaires and scales administered by the research team. Participants with previous diseases associated with the upper limb that could interfere with functional capacity or pain perception, patients with diagnosed fibromyalgia, if they had undergone previous surgical interventions that conditioned the functionality or pain of the upper limb regardless of the RD they suffered, or if they had diagnosed cognitive alterations were excluded. Data collection took place in each of the participating centres, and an occupational therapist from the research team was assigned to each centre to collect the baseline data and enter them into the database. Each subject was assigned a number, which was subsequently randomised in order to maintain anonymity throughout the process. This study complied with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist of elements of observational cohort studies.17

ProcedureParticipants were recruited between February and November 2022 by consecutive sampling as they attended the sessions scheduled at the OT Department of the Rheumatoid Arthritis and Spondylitis Association centre in Móstoles, Madrid, and the Tecan Centre, Clínica de la Mano, Málaga, where OT interventions are carried out for the treatment of RA-related symptoms affecting the upper limb. After unifying the criteria in both centres, the procedure to be followed by the different professionals for data collection was pooled.

MeasurementsOn the one hand, socio-demographic data were collected, such as age, current employment status, dominant hand and the hand most affected by the disease. With regard to the assessment scales used for this study, the following were used:

- -

The Spanish scale of rheumatic diseases and self-efficacy, to assess how RD pain affects their daily activity and skills to control the disease. This questionnaire has a Cronbach’s alpha of .87 and a two-half correlation of .88.18 The items are scored using a Likert scale, using scores from 1 to 10,19 and can be divided into 3 blocks depending on the subject matter, with one block of items dealing with the patient’s symptomatology, the functionality of the upper limb and the pain the patient feels in reference to self-efficacy.

- -

The visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to measure the intensity of pain perceived by the subject in millimeters,20 with a score range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (unbearable pain). The cut-off points used by this scale are <4 points for mild-moderate pain, 4–6 points for moderate-severe pain intensity and >6 for severe pain intensity. This scale has a reliability of .94–.98.21

- -

We used the QuickDASH questionnaire to assess functional disability of the upper limb in the performance of activities.22 It is a short version of the Disability Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire.23,24 The QuickDASH consists of 11 questions and retains the reliability and validity, as well as the characteristics of its original, longer version.25 Items are scored from 1 to 5, with 0 “no difficulty, pain or symptom” as the lowest score and 5 “unable, total limitation or pain” as the highest score.

For the analysis of results, a database was constructed from the information collected from the participants’ data collection notebooks and the self-administered questionnaires. The analysis was oriented towards the search for significant correlations between the study variables. The sample was tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics were performed for the socio-demographic and clinical data, with measures of central tendency and dispersion of the study variables and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used for parametric samples. Regression analysis was used to study the predictive value of the functional variables (QuickDASH and pain) to explain the dependent variable (Spanish scale of rheumatic diseases and self-efficacy). For the inclusion of the variables in the model, the probability had to be <.5.

The interpretation of the correlation coefficients: r < .39 low relationship; .4 < r < .69 moderate relationship; r > .7 high relationship. Significance level p = .05.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® software (version 21.0).

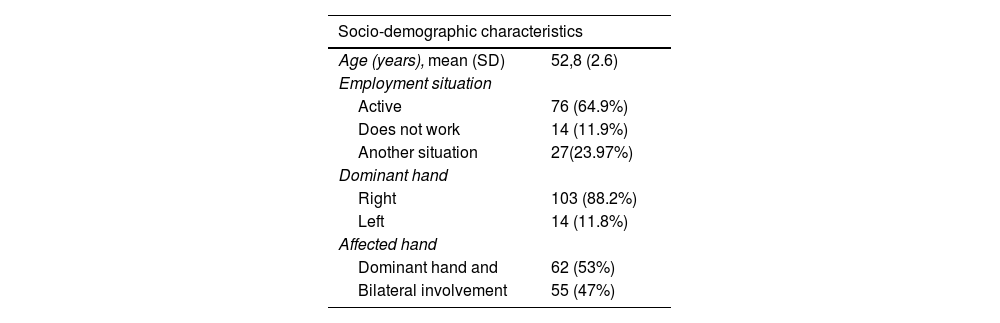

ResultsA total of 117 women participated in the study with a mean age of 52.8 (SD = 2.6) years. In reference to employment status, a total of 76 women (64.9%) were in employment, while 14 (11.9%) were inactive and 27 of them reported having “other status” (23.07%). One hundred and three (n = 103) participants reported using their right hand as dominant (88.2%). In reference to disease involvement, 62 participants (53%) showed dominant hand involvement and 55 of them (47%) bilateral involvement at the time of the study (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of the participants.

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 52,8 (2.6) |

| Employment situation | |

| Active | 76 (64.9%) |

| Does not work | 14 (11.9%) |

| Another situation | 27(23.97%) |

| Dominant hand | |

| Right | 103 (88.2%) |

| Left | 14 (11.8%) |

| Affected hand | |

| Dominant hand and | 62 (53%) |

| Bilateral involvement | 55 (47%) |

SD: standard deviation.

Mean (standard deviation) and absolute frequency (%) for socio-demographic characteristics.

In order to analyse which functional variables (QuickDASH and pain) are the best predictors of self-efficacy measured with the Spanish scale of rheumatic diseases and self-efficacy, a series of linear regression analyses were performed using self-efficacy as the dependent variable. For this purpose, we introduced the functional variables of pain and function (VAS and QuickDASH). As our aim is to find among the variables studied those that best explain the dependent variable without any of them being a linear combination of the others, we used the “stepwise” procedure. For the inclusion of the variables in the model, the probability had to be <.5.

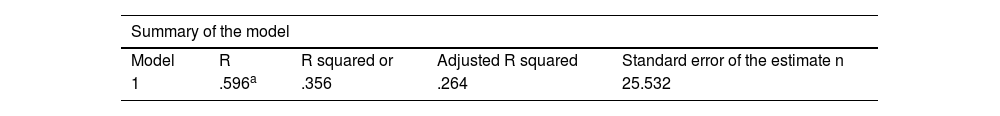

A directly proportional relationship was found between self-efficacy, pain intensity and upper limb functionality (p < .05). The level of association between self-efficacy, pain intensity and QuickDASH is 35%, with an R2 = .356 (Table 2).

Summary of the model with self-efficacy variable.

| Summary of the model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | R | R squared or | Adjusted R squared | Standard error of the estimate n |

| 1 | .596a | .356 | .264 | 25.532 |

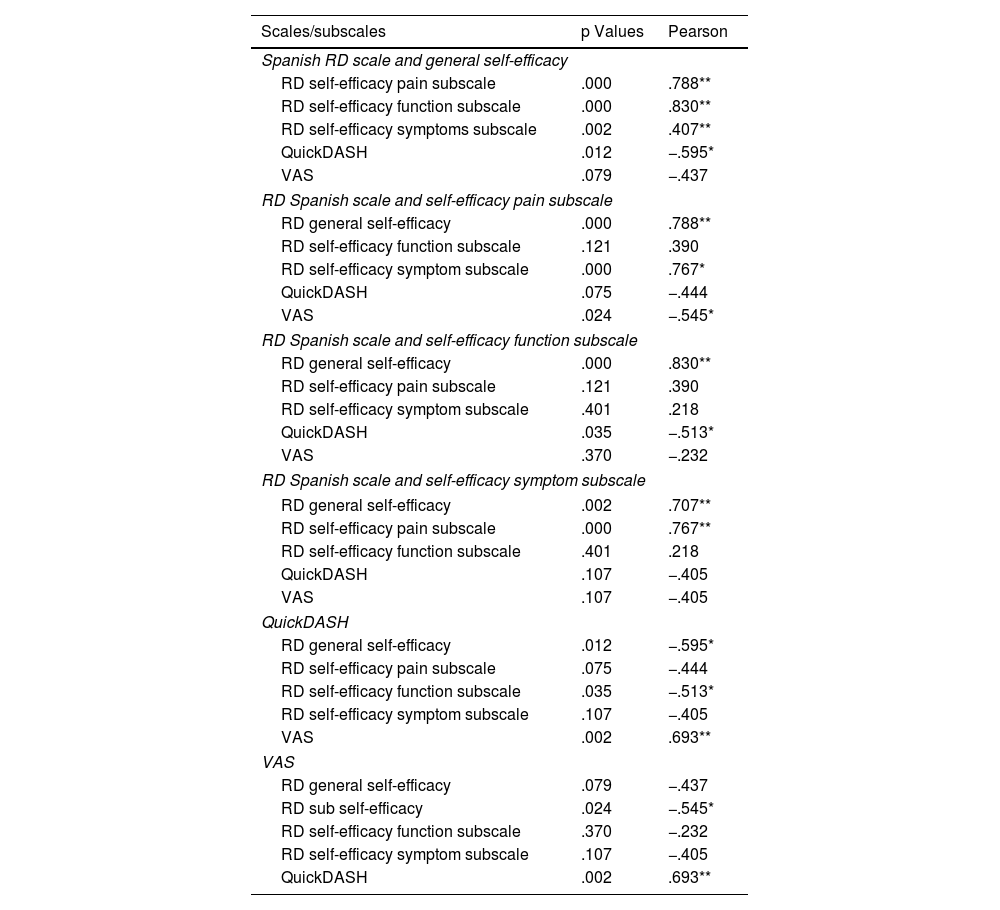

Specifically, the variables measuring self-efficacy show a low correlation with the VAS scale (r = −.437; p = .079) and a high correlation with the QuickDASH questionnaire (r = −.595; p = .012). Regarding the variables that measure pain intensity, the Spanish scale of rheumatic diseases and general mastery self-efficacy shows a low relationship (r = −,437; p = .079), while the domain-specific pain self-efficacy scale shows a high relationship (r = −.545; p = .024) as with the QuickDASH questionnaire (r = −.693; p = .002). Finally, the variable measuring upper limb functional disability, the Spanish scale of rheumatic diseases and general mastery self-efficacy, presents a moderate relationship (r = −.595; p = .012), while the domain-specific one in relation to function, shows a moderate relationship as well (r = −.513; p = .013), and with VAS it shows a high relationship (r = −.693; p = .02) (Table 3). Upper limb functional ability and pain intensity have a significant negative correlation with self-efficacy (<.01).

Bivariate correlations between variables of the Spanish scale of rheumatic diseases mad general and specific self-efficacy, QuickDASH and VAS.

| Scales/subscales | p Values | Pearson |

|---|---|---|

| Spanish RD scale and general self-efficacy | ||

| RD self-efficacy pain subscale | .000 | .788** |

| RD self-efficacy function subscale | .000 | .830** |

| RD self-efficacy symptoms subscale | .002 | .407** |

| QuickDASH | .012 | −.595* |

| VAS | .079 | −.437 |

| RD Spanish scale and self-efficacy pain subscale | ||

| RD general self-efficacy | .000 | .788** |

| RD self-efficacy function subscale | .121 | .390 |

| RD self-efficacy symptom subscale | .000 | .767* |

| QuickDASH | .075 | −.444 |

| VAS | .024 | −.545* |

| RD Spanish scale and self-efficacy function subscale | ||

| RD general self-efficacy | .000 | .830** |

| RD self-efficacy pain subscale | .121 | .390 |

| RD self-efficacy symptom subscale | .401 | .218 |

| QuickDASH | .035 | −.513* |

| VAS | .370 | −.232 |

| RD Spanish scale and self-efficacy symptom subscale | ||

| RD general self-efficacy | .002 | .707** |

| RD self-efficacy pain subscale | .000 | .767** |

| RD self-efficacy function subscale | .401 | .218 |

| QuickDASH | .107 | −.405 |

| VAS | .107 | −.405 |

| QuickDASH | ||

| RD general self-efficacy | .012 | −.595* |

| RD self-efficacy pain subscale | .075 | −.444 |

| RD self-efficacy function subscale | .035 | −.513* |

| RD self-efficacy symptom subscale | .107 | −.405 |

| VAS | .002 | .693** |

| VAS | ||

| RD general self-efficacy | .079 | −.437 |

| RD sub self-efficacy | .024 | −.545* |

| RD self-efficacy function subscale | .370 | −.232 |

| RD self-efficacy symptom subscale | .107 | −.405 |

| QuickDASH | .002 | .693** |

RD: rheumatic diseases; Spanish RD general self-efficacy scale: Spanish RD scale and self-efficacy subscale: Spanish scale of rheumatic diseases and self-efficacy subscales; VAS: visual analogue scale.

In the step-by-step analysis, using self-efficacy as the dependent variable and pain and function as predictors. The most significant model is obtained using as independent variables the pain variable and the function variable with an R = .596 and an R2 = .35 with a significance level of p = .000.

Therefore, function (QuickDASH) and pain (VAS) are predictor variables in the rheumatic hand with a standardised B coefficient = 78.561 (p = .000), with neither separately being more predictive than the other.

DiscussionIn this study we found a correlation between self-efficacy, pain intensity and functional disability of the upper limb in patients with RA. The results obtained indicated the contrast of the main hypothesis, which established a relationship between variables, since a high score on the VAS also implied a high score on the QuickDASH questionnaire and the Spanish scale of rheumatic diseases and general self-efficacy and, therefore, greater pain intensity, greater functional disability and lower self-efficacy of the subject, but without any variable being more predictive than another. This may be due to the fact that upper limb function measured with the QuickDASH scale and pain measured with the VAS scale have a positive correlation, similar to the results presented in the studies of Kadzielski et al.26 and MacDermid et al.,27 and those of Goldfarb and Stern28 and Barthel et al.,29 where a relationship is established with a high level of significance (p < .001) between the variables function and pain in patients with rheumatic diseases. Our results are consistent with previous studies establishing a possible relationship between self-efficacy and functional disability,30,31 as well as self-efficacy and its relationship with physical functions such as strength, range of motion and hand coordination,9 demonstrating that a low level of self-efficacy implies a decrease in functionality. The results of our research also concur with the results obtained recently by Rodríguez-García et al.,4 a study with a similar design to ours, a multicentre, observational, cross-sectional study, which demonstrates the relationship between self-efficacy, pain intensity and functional disability, also taking into account the duration of the disease and the performance of activities of daily living (ADLs).4 However, in the study by Rodriguez-Garcia et al., despite the larger sample size, there is heterogeneity in the sample, as it includes patients with rheumatic involvement and patients with degenerative osteoarthritis of the base of the thumb where the rest of the fingers are not affected in daily activities and where the result of the DASH scale may not be conclusive as this scale, which assesses the global disability of both upper limbs, may not be specific for osteoarthritis of the base of the thumb and may not be sensitive to changes.

Other studies relate in their results a high level of self-efficacy to correct occupational performance, focusing specifically on basic activities of daily living (BADL).26 RA is a disease whose main symptom is pain, being one of the constant symptoms in RD, which is defined as “disabling and intense”32 and therefore, self-efficacy and upper limb functionality will be affected by the intensity of the subject’s pain, so that the pain variable and occupational performance could also have a positive correlation, as demonstrated in the study by Cantero-Téllez et al. where patient satisfaction, perception and pain intensity show correlative data.33 We therefore believe that pain should be a priority target for intervention in RA, since its improvement will lead to an increase in the self-efficacy and functionality of the subject, as demonstrated in numerous studies that point out that the main consequence of pain is the deterioration of functionality, resulting in a limitation of independence and autonomy, which in turn affects self-efficacy, the patient’s quality of life and the occupations performed.34–38

With regard to symptomatology, it should be noted that RA presents with symptoms involving an alteration of the joint structures that lead to a loss of functionality of the patient’s upper limb. In their study, Blazar et al.39 demonstrate not only the inability of subjects to perform activities such as manipulating an object, but also the loss of functionality of the upper limb and occupational performance, which is often triggered by the subject’s abstention from performing specific manual activities. Given that these symptoms appear in more advanced stages of the disease, and that our sample has a mean age of 52.8 years, which can be considered young and not very advanced in the disease, we have not been able to assess whether and to what extent these factors may influence the functional capacity of the subjects. Larger, more heterogeneous samples would be necessary to determine this fact.

The preliminary conclusions drawn from this study could help in the design and planning of individualised assessments and interventions to address different factors related to functional disability of the upper limb, as well as to promote the development of early interventions that prioritise self-efficacy, since its improvement would also imply an improvement in the independence and autonomy of patients, reducing the number of resources in terms of assessment scales during the patient's intervention process. The implementation of the self-efficacy scale from an interdisciplinary approach together with rheumatologists, nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists among other health professionals, will allow self-efficacy to acquire greater significance and, therefore, interventions to be more oriented to the patient’s needs and their satisfaction. Future research with longitudinal multicentre studies with a larger number of subjects where more clinical and psychological variables are included could help us to obtain representative results in the Spanish RA population.

LimitationsAs this was a cross-sectional study with a single data collection, we cannot determine cause-effect, nor can we consider other factors that may condition the response of a subject in a given situation. Another limitation could be a type 1 bias in the procedure, since the study data were not extracted in their entirety by a single person, but by a representative of each centre, with two researchers in charge of this. Furthermore, the population included had pain levels above 4 out of 10, and since many RA patients have lower values on the pain scale, the results cannot be extrapolated to the entire RA population.

ConclusionsThere is a positive correlation between self-efficacy, function and pain in patients diagnosed with RA. Therefore, the results suggest that the systematic use of the Spanish scale of rheumatic diseases and self-efficacy in isolation could be used as a single assessment method whose outcome would encompass functionality and pain intensity in patients with RA.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.