VEXAS syndrome is a rare entity secondary to UBA1 gene mutations, located on the X chromosome. This mutation generates, as a consequence, a characteristic vacuolation on haematopoietic stem-cells. It is characterized by multiple autoinflammatory and haematologic manifestations, which respond and end up being dependent on corticosteroid treatment. In this publication we present a 2-case series diagnosed at our hospital and make a brief literature review of the published evidence so far.

El síndrome VEXAS es una entidad infrecuente secundaria a una mutación en el gen UBA1, localizado en el cromosoma X. Esto provoca como consecuencia la aparición de vacuolas, característica de esta patología, en células madre hematopoyéticas. Se caracteriza por la aparición de múltiples manifestaciones autoinflamatorias sistémicas y hematológicas, que responden y acaban siendo dependientes al tratamiento con glucocorticoides. En la presente publicación aportamos una serie de 2 casos diagnosticados en nuestro centro, y realizamos una breve revisión de la evidencia publicada al respecto.

VEXAS syndrome is classified as an autoinflammatory disease. It is caused by mutations in the UBA1 gene, and first described by Beck et al. in 2020.1 The term VEXAS is an acronym formed by the first letters of the fundamental characteristics of the disease1,2:

- -

Vacuoles: presence of cytoplasmic vacuoles in haematopoietic stem cells.

- -

E1 ubiquitin-ligase enzyme: a mutation occurs in the UBA1 gene, which encodes this ubiquitin-activating enzyme.

- -

X chromosome: where the UBA1 gene is located.

- -

Autoinflammatory.

- -

Somatic: the mutation is acquired and non-heritable, present in haematopoietic stem cells and absent in other cells.

The clinical manifestations of this entity are very varied, the most frequent being haematological, cutaneous, rheumatological, and pulmonary involvement.2 In addition, corticodependence is characteristic, with the onset of new outbreaks when the dose of glucocorticoids (GCs) is lowered, making it very difficult to discontinue them.3 The following is a series of 2 significant cases diagnosed in our centre, and a brief review of these cases.

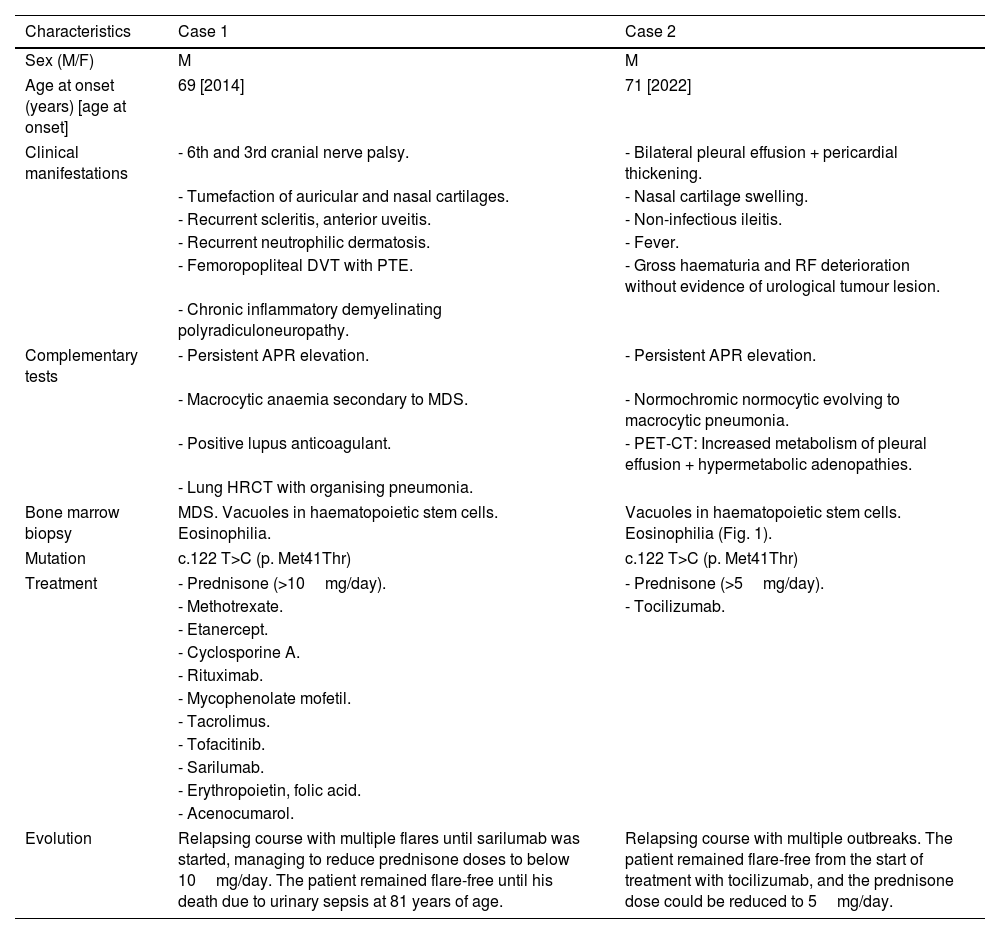

Clinical observationTable 1 summarises the relevant clinical data of each case, the treatments received, and their progression. Of note, onset in both patients was at around 70 years of age, developing corticodependent symptoms, especially nasal chondritis and macrocytic anaemia, and reached clinical stability with anti-interleukin-6. In case 1, ocular and cutaneous symptoms predominated, together with the onset of thrombotic phenomena, while case 2 had pulmonary, renal, and gastrointestinal manifestations.

Description of clinical cases of VEXAS syndrome diagnosed in our hospital.

| Characteristics | Case 1 | Case 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F) | M | M |

| Age at onset (years) [age at onset] | 69 [2014] | 71 [2022] |

| Clinical manifestations | - 6th and 3rd cranial nerve palsy. | - Bilateral pleural effusion + pericardial thickening. |

| - Tumefaction of auricular and nasal cartilages. | - Nasal cartilage swelling. | |

| - Recurrent scleritis, anterior uveitis. | - Non-infectious ileitis. | |

| - Recurrent neutrophilic dermatosis. | - Fever. | |

| - Femoropopliteal DVT with PTE. | - Gross haematuria and RF deterioration without evidence of urological tumour lesion. | |

| - Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. | ||

| Complementary tests | - Persistent APR elevation. | - Persistent APR elevation. |

| - Macrocytic anaemia secondary to MDS. | - Normochromic normocytic evolving to macrocytic pneumonia. | |

| - Positive lupus anticoagulant. | - PET-CT: Increased metabolism of pleural effusion + hypermetabolic adenopathies. | |

| - Lung HRCT with organising pneumonia. | ||

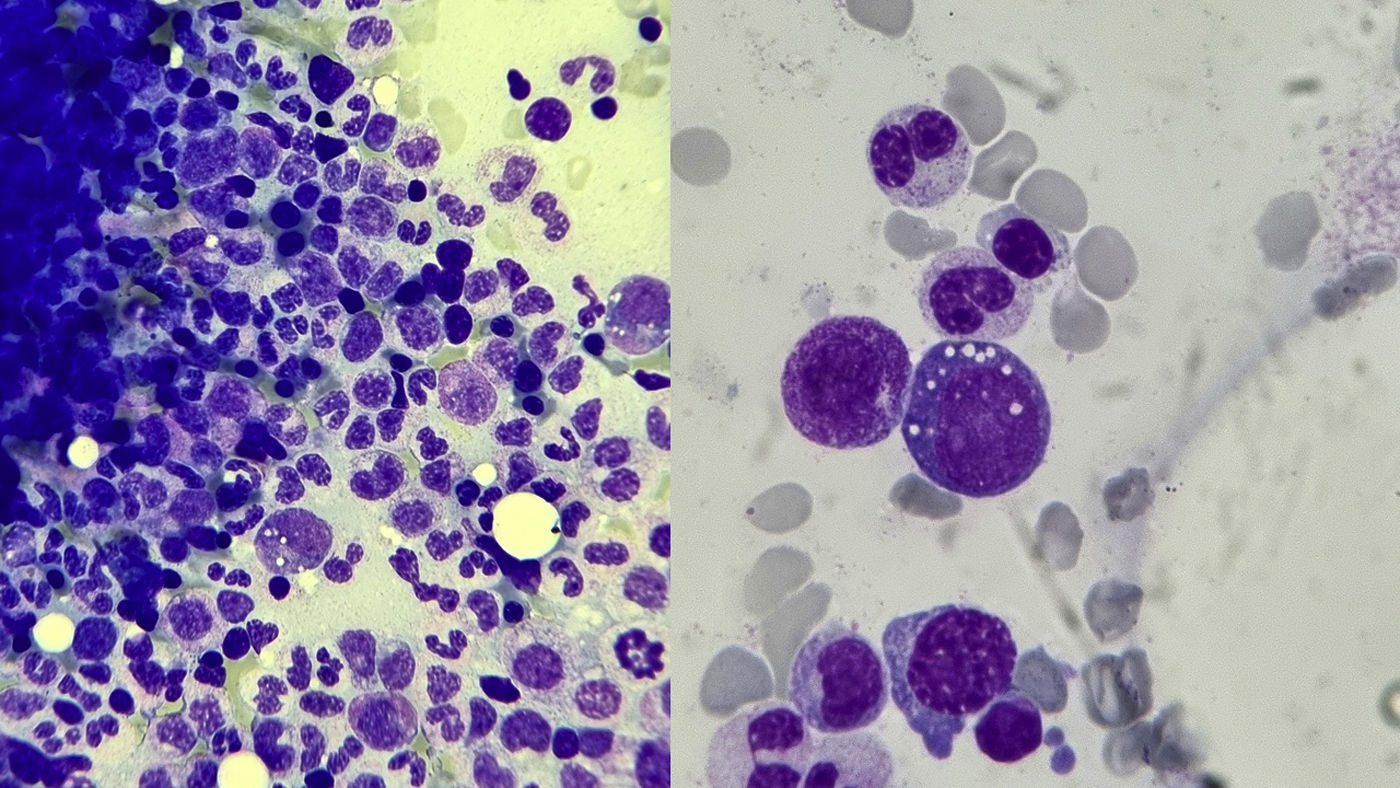

| Bone marrow biopsy | MDS. Vacuoles in haematopoietic stem cells. Eosinophilia. | Vacuoles in haematopoietic stem cells. Eosinophilia (Fig. 1). |

| Mutation | c.122 T>C (p. Met41Thr) | c.122 T>C (p. Met41Thr) |

| Treatment | - Prednisone (>10mg/day). | - Prednisone (>5mg/day). |

| - Methotrexate. | - Tocilizumab. | |

| - Etanercept. | ||

| - Cyclosporine A. | ||

| - Rituximab. | ||

| - Mycophenolate mofetil. | ||

| - Tacrolimus. | ||

| - Tofacitinib. | ||

| - Sarilumab. | ||

| - Erythropoietin, folic acid. | ||

| - Acenocumarol. | ||

| Evolution | Relapsing course with multiple flares until sarilumab was started, managing to reduce prednisone doses to below 10mg/day. The patient remained flare-free until his death due to urinary sepsis at 81 years of age. | Relapsing course with multiple outbreaks. The patient remained flare-free from the start of treatment with tocilizumab, and the prednisone dose could be reduced to 5mg/day. |

The table shows sex, age, clinical manifestations, main disorders noted in complementary tests, abnormalities observed in the bone marrow biopsy, mutation diagnosed, treatments received and clinical course.

APR: acute phase reactants; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; F: female; M: male; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism; RF: renal function.

VEXAS syndrome is an autoinflammatory disease due to an acquired mutation in bone marrow haematopoietic stem cells at codon p.Met41 of the gene encoding the E1 ubiquitin ligase enzyme (UBA1), located on the short arm of the X chromosome (Xp11.23).4 There are 3 mutations in UBA1 recognised as pathogenic for VEXAS syndrome (p.Met41Thr, p.Met41Leu, and p.Met41Val), the latter being associated with greater clinical severity and mortality.2,5 Other mutations have recently been identified in atypical locations of the same gene.6 All haematopoietic progenitors have these mutations, especially in myeloid cells (neutrophils and monocytes), and they are absent in mature lymphocytes. This mosaicism would be because the appearance of the mutation in lymphoid cells facilitates their apoptosis and is incompatible with their cell survival,6 leading to lymphopenia in patients, and the few surviving circulating lymphocytes do not carry mutation for the UBA1 gene.

Regarding epidemiology, as in our series, the typical patient with VEXAS syndrome is usually male, over 50 years of age, white,2,3 with exceptional cases described in women. It is hypothesised that this is because the expression of the UBA1 gene escapes inactivation of the second X chromosome in women, making it more unlikely for a woman with a mutation in the non-inactivated chromosome to develop the disease.7

Its pathogenesis is not yet well understood. It is related to the presence of the mutation in haematopoietic precursors and their derived cells, especially neutrophils and monocytes.2 This would lead to the overexpression of various cytokines, precipitating uncontrollable proinflammatory neutrophil activation and giving rise to the clinical picture,8 and also causing a change in the bone marrow microenvironment, thus the appearance of the haematological abnormalities described.2

The clinical symptoms of VEXAS syndrome are very varied and affect different body systems.4,7 As in our series, these manifestations are characteristically corticodependent, responding rapidly to high doses of GCs and relapsing with lowering doses.3,4 At the haematological level, macrocytic anaemia tends to occur in practically all patients,2 as we see in our series, as well as other associated cytopenia. Approximately half the patients eventually develop myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), as in one of our cases, which usually presents low-risk phenotypes, as well as thrombotic episodes (especially deep vein thrombosis), a consequence of the chronic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction caused.9 At the cutaneous level, the most frequent lesions are neutrophilic dermatosis, as in case 1 of our series, cutaneous vasculitis and septal panniculitis.8 At the rheumatological level, patients often develop recurrent fever, constitutional symptoms, and lymphadenopathy. Recurrent polychondritis is quite common, as observed in our series, with involvement of nasal and auricular cartilages.2 At the pulmonary level, cough and dyspnoea may appear, simulating pneumonia or decompensation of heart failure resistant to treatment with diuretics or antibiotics,2 and interstitial pulmonary infiltrates, consolidations, or pleural effusion (as in our case 2), among others, are frequent. At the ocular level, episcleritis, scleritis, and uveitis,2 as we can see in case 1 of our series. Pericarditis and peripheral nervous system disorders have also been described, as in our case 1, and even gastrointenstinal2 or renal disorders (haematuria and proteinuria), as in our case 2, among others.

To diagnose the syndrome, genetic testing is essential in patients with compatible symptoms.8 Visualisation of cytoplasmic vacuolation of haematopoietic precursors in the bone marrow aspirate and biopsy is also characteristic, although not pathognomonic (Fig. 1), especially in myeloid and erythroid precursors.1 We should remember that intracytoplasmic vacuoles can also be found in acute alcohol intoxication, sepsis, zinc intoxication, multiple myeloma, copper deficiency, or even in MDS not associated with VEXAS syndrome.2,7,8

Bone marrow biopsy from our patient number 2. Giemsa-stained histological specimen. Optical microscope view at 50x magnification (×50, left) and at 100x magnification (×100, right). The myeloid series is well represented, with no maturational arrest and no increase in blast cells. Particularly noteworthy is the cytoplasmic vacuolation in myeloid cells, characteristic of VEXAS syndrome. In the sample obtained we also observed minimal dysplastic changes in the erythroid series, as well as the presence of marked eosinophilia.

There is still no standardised treatment for VEXAS syndrome. Most treatment recommendations are based on clinical experience and evidence from a few retrospective studies.2 The fundamental goals of treatment are to control inflammation, prevent associated complications (infections, cytopenia, and thrombotic events) and eliminate haematopoietic clones with the mutated UBA1 gene.

When it comes to controlling inflammation, as we have seen in our series, high-dose GCs are rapidly effective (with a minimum of 15−20mg/day of prednisone), allowing rapid control of symptoms.1,3,4 The response to classical drugs is very limited, with methotrexate and cyclosporin A being the most commonly used, with little success.3,4,8 Better responses have been obtained with various biological drugs, especially with anti-interleukin 1 (such as anakinra or canakinumab), anti-interleukin 6 (tocilizumab or sarilumab, as in our series), or JAK kinase inhibitors (ruxolitinib seems to be better than others in its therapeutic group, although the thrombotic risk should limit its use unless the patient is already anticoagulated, as in our case 1).2–4,8,10 As strategies to eliminate the mutated cells, allogeneic transplantation of haematopoietic progenitors can be considered in patients with a worse prognosis, leaving medical treatment with DNA methyltransferase inhibitors or JAK inhibitors for those with a better prognosis or with contraindications to transplantation.2,3 As for the prevention of associated complications, both infectious prophylaxis and vaccination have been recommended in these patients.2–4 Both transfusions and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents can be used to control cytopenia.3 Finally, indefinite antiplatelet therapy is recommended in patients who have had thrombotic events. Primary antithrombotic prophylaxis is still under debate, given the lack of data.2,3

ConclusionRecently identified in 2020, VEXAS syndrome is still a novel and probably underdiagnosed disease. There is still a long way to go to fully characterise the disease and to find effective targeted therapies to control all autoinflammatory manifestations safely and effectively.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.