Frida Kahlo's medical history shows sequelae of polio, a severe traumatic event that caused multiple fractures and a penetrating pelvic injury, as well as a history of countless surgeries. In her biographical accounts and her works, chronic disabling pain always appears for long periods. Besides, a chronic foot ulcer, gangrene that required amputation of the right leg, a history of abortions, and a positive Wasserman reaction suggest that the artist could have suffered from antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS).

La historia clínica de Frida Kahlo muestra secuelas de polio, un evento traumático grave que causó múltiples fracturas y una lesión penetrante de pelvis, así como historia de incontables cirugías. En sus recuentos biográficos y en sus obras, siempre aparece dolor crónico incapacitante por largos periodos. Además, una úlcera crónica del pie, gangrena que requirió la amputación de la pierna derecha, la historia de abortos y una reacción de Wasserman positiva sugieren que la artista podría haber padecido síndrome antifosfolipídico (SAF).

Frida Kahlo is an icon among 20th-century women in the arts. Interest – and even devotion – about her works, remain more than 50 years after her death. Younger generations know about her and usually have a position on her paintings, whether they like them or not. Frida has been the subject of several biographic and iconographic books and some popular motion pictures. She is the center of many web sites and is represented in numerous examples of popular arts and crafts, particularly in her natal Mexico. Her personality has become a symbol embraced by activists of feminism and sexual liberation, persons with a disability, and Mexican culture.1–7 She is also probably the painter with more medical papers centered on her health.

The purpose of this paper is to review some historical pieces of evidence to explain the cause of some of her medical problems, namely, primary antiphospholipid syndrome.

Case reportFrida Kahlo was born in Mexico City in 1907, the 3rd of 4 daughters. Her father had a history of epilepsy, and her mother suffered fits that had apparently psychological basis. Her sister Adriana suffered three spontaneous abortions.1–3,6 Frida had a severe condition diagnosed as Polio at the age of 6, which, after a prolonged evolution, requiring bed rest for nine months, left moderate atrophy and weakness in her right leg as well as some discrepancy in length with the left side. Eventually, her recovery allowed her to run and dance. She used dressing tricks to hide the slight difference among her legs, but still had some pelvic imbalance and probably some degree of scoliosis (diagnosed later in her life).3,6,8–10 On September 17, 1925, at the age of 18, the bus she was traveling in collided with a streetcar. This accident caused her several fractures in vertebrae, clavicle, pelvis, and right leg and foot; luxation of the left elbow and a penetrating wound caused by a metal handrail which entered on the left side of the pelvis and emerged through the left side of her vulva. She developed peritonitis requiring surgery and had cystitis after prolonged catheterization. After she recovered from these problems, persistent back pain led to the diagnosis of vertebral fractures, starting the use of several different types of plaster and metal corsets for prolonged periods for the rest of her life. By 1931, X-ray studies of the spine showed the existence of spina bifida and scoliosis, besides of the traumatic lesions. After that, she had multiple spine surgeries in diverse hospitals.3,6,8–12 An X-Ray film of 1954 – the year of her death – shows a metal bar fixed by screws from 3rd to 5th lumbar vertebrae.10

Since 1931 she suffered persistent and severe pain in the right leg and foot, with remarkable thinning of that limb. She required for the rest of her life, the use of diverse narcotic analgesics, which she combined with alcohol in varying forms and quantities.3,6 A small ulcer appeared on the right foot, as it persisted and increased its size, leading to several surgeries on that foot, including amputation of phalanxes and sesamoid bones and a sympathectomy. Finally, as gangrene complicates the case, her right leg was amputated until the knee in 1953. It should be noted that Frida was a heavy smoker, a risk factor for both, chronic ulcers and gangrene.6

Several of her biographers refer to multiple miscarriages, including two therapeutic abortions: one in 1929 (attempting to prevent complications from her damaged pelvis) and one in 1934. At least two spontaneous abortions occurred. One in 1932, after four months of pregnancy, while in Detroit, and another in 1937. The other miscarriages have not been defined clearly as to when and where they occurred.3,6,13,14

In 1931, she had a positive Wassermann's test when she was studied in San Francisco by Dr. Leo Eloesser, a Surgeon at San Francisco, who became his life-long friend and main medical advisor. The positive Wassermann test led to treatment with Neosalvarsan and later to therapies with blood transfusions and bismuth, considering that syphilis could explain some of her problems. The laboratory reaction was negative in several other times.3,6,15

From this time, she had long periods of severe limitation due to fatigue and pain, mainly in her neck, back, and right leg, accompanied with weight loss and depression. She could not continue giving her painting lessons. After one of her spine surgeries, while lying on her bed or limited to a wheelchair, she painted many of her works.3,6,8–12

In 1954, after attending a political manifestation, against her doctors’ advice, she fell ill with pneumonia and died on July 13, that year. Her death certificate (signed by her Psychiatrist, Dr. Ramón Parres) refers to “pulmonary embolism” as the cause of her death,3,6 although no autopsy was performed. Some of her biographers mention the possibility that a narcotic overdose, either voluntary or not, could have influenced her outcome.3

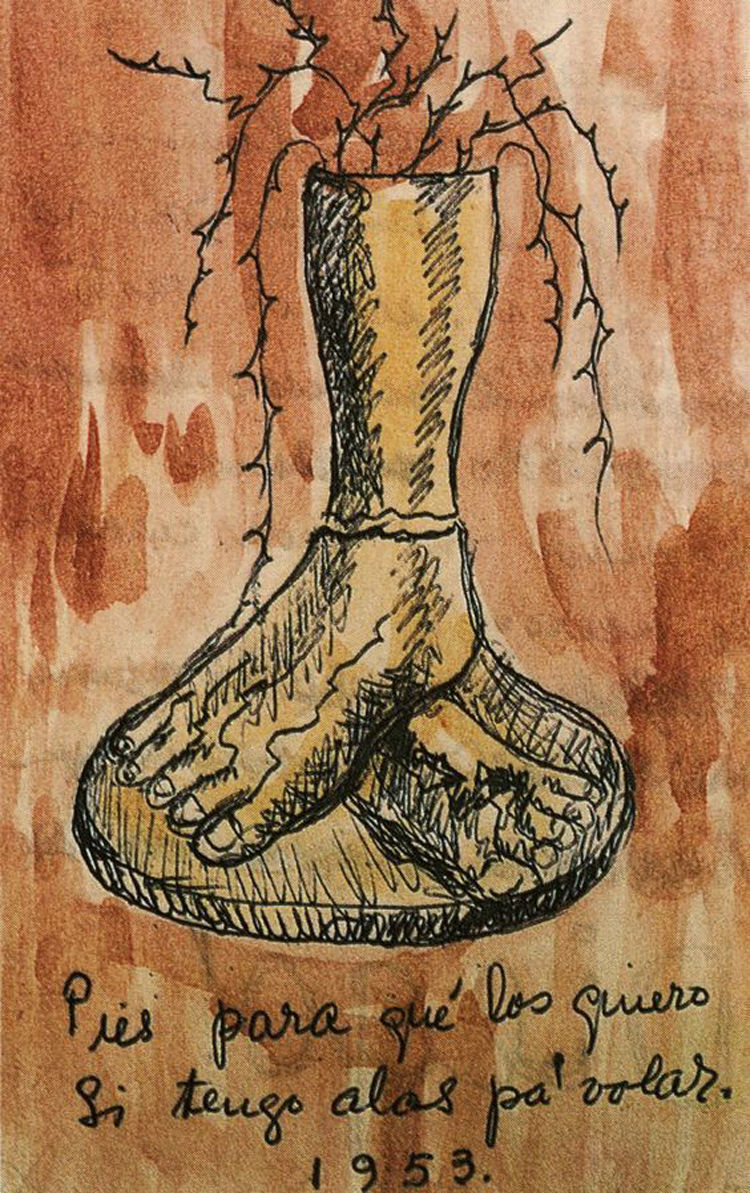

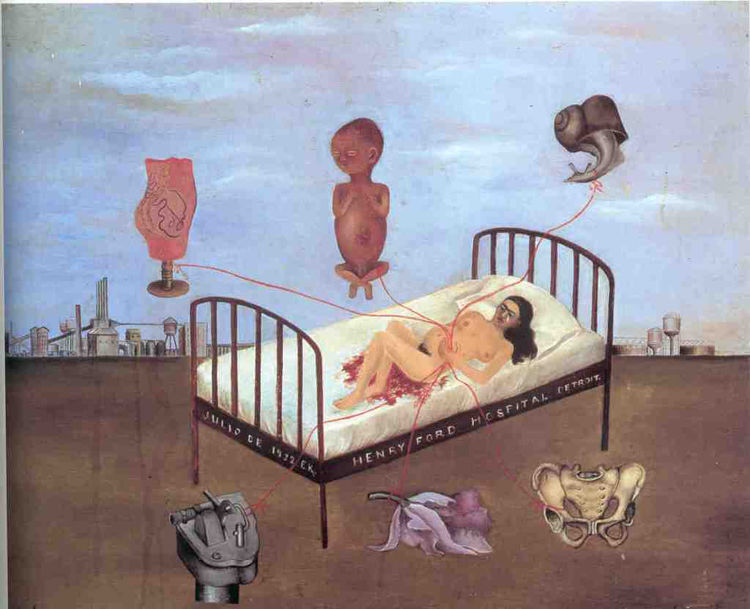

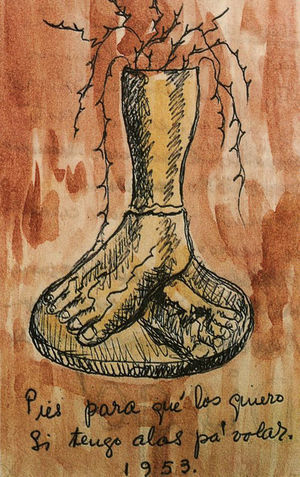

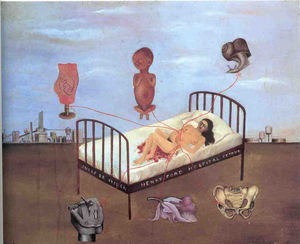

Like many episodes of her life, Frida illustrated some of her clinical features in her works. The painting, known as “What I saw in the water” (Fig. 1; oil on canvas, 1938; 91cm×70.5cm. Daniel Filipacchi's collection, Paris),4 shows a bleeding sore by her deformed, right first toe. A drawing known as “Self-portrait, sitting” (pencil on paper, 1931; 29cm×20.4cm. Teresa Proenza's Collection, Mexico City),4 show her sitting with a bandaged left foot that shows a dark stain. A similar painting, “Remembrance of the open wound,” is little known as a fire destroyed the owner's house. This painting shows her with a bleeding wound in her left thigh, apparently invented as there is not an account of such lesion, but it also shows a bandaged and bleeding left foot again. It is known only from a photograph owned by Raquel Tibol.6 After that, her diary, which she started in 1946; includes a drawing of a severed right leg and foot (Fig. 2; watercolor and ink on a paper page, 1953; Frida Kahlo's Museum, Mexico City) with the famous legend “Feet, what do I need them for if I have wings to fly”.4 Another drawing from the same Diary (watercolor and ink on a paper page, 1954; Frida Kahlo's Museum, Mexico City) shows Frida with a wooden leg, again on the left side. Chronic ulcer, disabling pain, and gangrene occurred on the right lower limb. The reason to depict an affected left side is not known. Is it intentionally misleading? Is it a mistake? It seems unlikely as it happens in at least three works. Regarding the abortions, two works dated in 1932 describe one of them. The lithography is known as “Frida and the abortion (lithography on paper, 2nd copy, 32cm×23.5cm; Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico City)4 and a painting titled “Henry Ford Hospital,” or “The flying bed” (Fig. 3, oil on metal sheet, 30.5cm×38cm; Dolores Olmedo Collection, Mexico City).4 Both works show her naked, with tears in her eyes, bleeding genitals and communicating lines to a fetus and other elements.

“Feet, what do I need them for if I have wings to fly”, watercolor and ink on a paper page, 1953; Frida Kahlo's Museum, Mexico City. D.R.© Fiduciario en el Fideicomiso relativo a los Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo. Av. 5 de Mayo No. 2, Col Centro, alc. Cuauhtémoc, c.p. 06000, Ciudad de México.

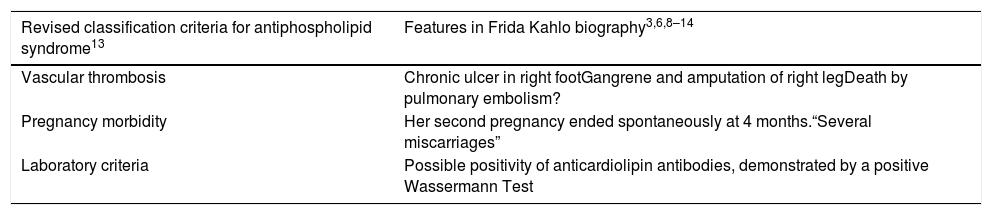

This summary of clinical features found in Frida Kahlo's biographic accounts and paintings would lead most contemporary Rheumatologists to investigate the possibility of primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Table 1 summarizes the findings in Frida's history and compares some of those features with currently accepted Criteria for the Classification of Antiphospholipid Syndrome.13 Knowledge on its epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management has progressed notably, and as a result, vascular and obstetric outcomes of this condition have improved.14

Features suggesting Antiphospholipid Syndrome in Frida Kahlo.

| Revised classification criteria for antiphospholipid syndrome13 | Features in Frida Kahlo biography3,6,8–14 |

|---|---|

| Vascular thrombosis | Chronic ulcer in right footGangrene and amputation of right legDeath by pulmonary embolism? |

| Pregnancy morbidity | Her second pregnancy ended spontaneously at 4 months.“Several miscarriages” |

| Laboratory criteria | Possible positivity of anticardiolipin antibodies, demonstrated by a positive Wassermann Test |

Several medical papers have explored possible explanations for her chronic pain, both in the right lower limb and generalized, as well as disability. They include the sequelae of trauma and vertebral fractures, with nerve root compromise, but some authors point to the relative importance of spina bifida8,10; complex regional pain syndrome8,10,15 and even to post-polio syndrome.8,10,15–17 Compelling pieces of evidence point to post-traumatic fibromyalgia,18 and some authors refer to lead poisoning.19

The chronic lesion, described as a “trophic ulcer” on the right foot, has been seen as a complication of severe trauma in a limb with neurological deficiencies from polio.3,6,8,10 Also, Post-Polio syndrome has been invoked.15–17 There is a possibility of osteomyelitis complicating her surgeries on that foot. However, as the lesion progressed, it was accompanied by signs of vascular insufficiency and finally gangrene. Therefore, previous explanations seem inadequate, and these findings suggest vascular thrombosis.

Frida's abortion (at four months of her second pregnancy), as well as the “multiple miscarriages” and the therapeutic abortions, have been explained as complications of her accident causing uterine damage or pelvic abnormalities.3,6,20,21 Attempts to explain her inability to carry a pregnancy to term, include an exploratory laparotomy performed in 1934 after an abortion, which found “ovarian infantilism”3,6 and recent reviews of her case mention the possibility of Asherman's syndrome (endometrial scarring).22

Wassermann's test was performed looking for syphilis.3,6 It was the usual test in those days. Frida had at least one positive test. Our present interest in this finding lies in the fact that it was a primitive way to find antibodies to cardiolipin.23 The coagulation inhibitor named “the lupus anticoagulant” was known since 195224; however, the concept of Antiphospholipid Syndrome arose only in 1983.25 Such a notion was far from being known by Frida's Doctors.

Several papers published in medical journals have centered on Frida Kahlo's life, works, and clinical history. A non-exhaustive search in PubMed and PMC on March 26, 2020, yielded 40 papers, including Frida Kahlo as the main or secondary object of the publication. Her name was mentioned in many more papers discussing pain, art, and related issues. Besides of the titles already mentioned here, some papers discuss the role of herself depicting her pain and her medical interventions26–32; the perspective of her case as seen by rheumatologists33,34; the sublimation of her suffering, pain, and loss, describing possible psychiatric explanations.35–42 Even her homoeroticism has been discussed.43 Two papers deal with the relationship with her physicians.44,45 Some articles describe specific paintings.46–49 Others report on museum exhibitions on Frida Kahlo50–52 and her importance as a relevant character in educational interventions for health professionals.53,54 None of these papers mention the possibility of antiphospholipid syndrome.

ConclusionHistorical accounts of pregnancy morbidity, vascular thrombosis, and at least one mention of a positive test for antibodies to cardiolipin support the possibility of an antiphospholipid syndrome explaining some of the medical problems of Frida Kahlo. Her works depict several clues to understand her pain and the diversity of medical issues. Observing her pictures frequently leads to an emotional reaction and to admiration of her ability to overcome adversity. After all, citing Courtney et al.,15it is how she chose to live life, not her death, for which she is remembered.

AuthorshipJMT and MCAC originated the conception and design of the study. All of the authors participated in gathering, analyzing and interpretation of data; critical review of its intellectual content and definitive approval of the final text

Source of financingThis investigation has not obtained any help from public agencies; commercial entities or non-profit organizations. Only authors’ own resources.

Conflict of interestNone.