Juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (JSLE) is a rare autoimmune disease with significant morbidity and mortality. Pulmonary manifestations in JSLE have not been comprehensively described in the literature to date.

ObjectivesTo report the frequency, clinical, and demographic characteristics of JSLE patients with pulmonary manifestations compared to those without.

MethodsUnited Kingdom (UK) JSLE Cohort Study participants aged<18 years at diagnosis, with ≥4 American College of Rheumatology (ACR-1997) criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), were eligible. Patients were grouped according to the presence or absence of pulmonary involvement. Pulmonary manifestations were described at diagnosis, 1-year, 2-year, and 5-year follow-up. Demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with/without pulmonary manifestations were compared.

Results480 JSLE patients were included. Overall, 24.8% had pulmonary manifestations; 22.7% at diagnosis, 19.1% at 1 year, 17.2% at 2 years, and 22.4% patients at 5 years after diagnosis. Overall, the commonest manifestation was pulmonary serositis. Pulmonary involvement was associated with higher American College of Rheumatology (ACR)-1997 scores (p<0.002) and higher pediatric version of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (pBILAG) scores (p<0.001) at diagnosis but there were no differences in Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinic Damage Index (SLICC-SDI) scores (p>0.05). pBILAG defined pulmonary involvement was associated with increased frequency of constitutional (48.3 vs 26.1%), musculoskeletal (49.1 vs 26.1%), gastrointestinal (10.3 vs 3.8%), and hematological (37.9 vs 20.6%) involvement (all p<0.05).

ConclusionPulmonary disease is common in JSLE. It is associated with wider organ involvement, suggesting a need for close monitoring and prompt treatment.

El lupus eritematoso sistémico juvenil (LESJ) es una enfermedad autoinmune rara con un impacto negativo en morbimortalidad. Las manifestaciones pulmonares en el LESJ no han sido descritas de manera exhaustiva en la literatura.

ObjetivosInformar sobre la frecuencia, las características clínicas y demográficas de los pacientes con LESJ con manifestaciones pulmonares en comparación con aquellos sin ellas.

MétodosFueron elegibles aquellos participantes de la cohorte «United Kingdom (UK) JSLE Cohort Study» que fueron diagnosticados siendo menores de 18 años, con≥4 criterios del ACR-1997 para LES. Los participantes se agruparon según la presencia o ausencia de afectación pulmonar. Se describieron las manifestaciones pulmonares en el momento del diagnóstico y después del diagnóstico a los 1, 2 y 5 años.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 480 pacientes con LESJ. En general, el 24,8% presentaron manifestaciones pulmonares; el 22,7% en el diagnóstico, el 19,1% al año tras el diagnostico, el 17,2% a los 2 años tras el diagnóstico y el 22,4% a los 5 años tras el diagnóstico. En general, la manifestación más común fue la serositis pulmonar. La afectación pulmonar se asoció con puntuaciones más altas del ACR-1997 (p<0,002) y puntuaciones más altas de la versión pediátrica del pBILAG (p<0,001) en el momento del diagnóstico, pero no hubo diferencias en las puntuaciones del SLICC-SDI (p>0,05). La afectación pulmonar definida por pBILAG se asoció con una mayor frecuencia de afectación constitucional (48,3 vs. 26,1%), musculoesquelética (49,1 vs. 26,1%), gastrointestinal (10,3 vs. 3,8%) y hematológica (37,9 vs. 20,6%) (todas p<0,05).

ConclusiónLa enfermedad pulmonar es común en el LESJ. Dicha enfermedad está asociada con una mayor afectación de órganos, lo que sugiere la necesidad de un seguimiento cercano y un tratamiento rápido.

Juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (JSLE), also known as childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE), is a severe multisystem autoimmune disease characterized by autoantibodies directed against nuclear antigens.1 The incidence of JSLE has been shown to range between 0.36 and 0.46 per 100,000 children in the United Kingdom.2 It is more common among non-Caucasian UK patients with more internal organ involvement and significant disease activity compared to adult SLE.1,3

Pulmonary manifestations in SLE range from pleurisy to pleural effusion, acute pneumonitis, pneumothorax, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolic disease, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary vasculitis, and shrinking lung syndrome.4 Respiratory manifestations can be directly caused by the disease or secondary to concomitant complications such as infections.5

The incidence and prevalence of pulmonary involvement have not been described comprehensively in the JSLE literature but they are much better described in adult SLE.6–9 Pulmonary manifestations may be an initial and/or life-threatening complication of SLE in children.10 These symptoms may arise from primary pulmonary dysfunction, a complication secondary to infection, or from a disease process in another organ such as renal failure leading to pulmonary edema.11 This study aimed to investigate the prevalence, demographic characteristics, and clinical features of pulmonary disease in JSLE patients enrolled in the national UK JSLE Cohort Study, exploring the association between pulmonary involvement and disease activity, co-existing organ involvement and organ damage.

MethodsThis study was based upon the UK JSLE Cohort Study, a multidisciplinary, multicenter collaborative network established in 2006 with the primary aim of determining the clinical characteristics of JSLE patients across the UK, as well as supporting a program of clinical translational research (for details, see https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/life-course-and-medical_sciences/research/groups/ukjsle/).12 The Study collects detailed clinical and demographic longitudinal data. The UK JSLE Cohort is managed by the national coordinating center in Liverpool, with participating institutions including most pediatric rheumatology/nephrology centers in the UK (n=23).

The Study has received ethics approval (National Research Ethics Service Northwest, Liverpool, UK, reference 06/Q1502/77). Patients and guardians (in case of patients unable to give consent) who participated in the study also provided consent or parental permission. The research was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

This study included 480 patients (404 females, 76 males, female to male ratio: 5:1) aged˂18 years at the time of diagnosis, fulfilling ≥4 American College of Rheumatology-1997 (ACR) classification criteria for SLE,13 and followed up between August 2006 and August 2021.

Demographics (gender, age at diagnosis, and ethnicity), classification criteria for SLE (ACR-1997), the pediatric version of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG; pBILAG2004) disease activity score,1 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinic Damage Index (SLICC-SDI),14 medication use, and laboratory test data were accessed from patients enrolled in the UK JSLE Cohort Study. All these classification criteria, disease activity and damage measures have been used extensively in cSLE.2,15,16

JSLE patients were assessed for pulmonary manifestations at baseline visit and approximately at one year (range 10–14 months), two years (range 22–26 months) and five years (range 58–62 months) following diagnosis using data captured by the ACR-1997 classification criteria,13 the pBILAG2004,1 adult BILAG-200415 and the SLICC-SDI score.14 For comparative analyses, patients were grouped according to the presence of pulmonary involvement (at any time between baseline visit and five years of follow-up) or absence of pulmonary involvement during five years of follow-up. The presence or absence of pulmonary involvement was defined using data on pulmonary manifestations captured by either the ACR-1997 classification criteria,13 and/or the pBILAG2004 score (1), and/or, the SLICC-SDI score.14

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using the “Statistical Package for the Social Sciences” (SPSS 26.0 for Windows) software. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine whether continuous variables had a normal distribution. Results were displayed as median values with interquartile ranges or counts and percentages. As appropriate, a comparison between groups was performed using Mann–Whitney U (for continuous data) or Chi-square tests (for categorical data). Statistical significance was assumed at p<0.05.

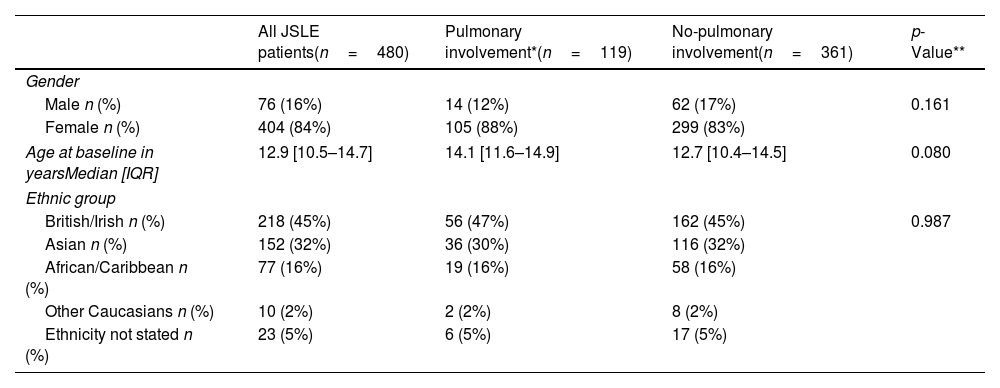

ResultsTable 1 presents the demographics of the patients. The median age of the participants was 12.9 (10.5–14.7) years at baseline. There were no statistically significant differences in the demographics of patients with or without pulmonary involvement.

Patient demographics for all JSLE patients, with a comparison of those with/without pulmonary involvement.

| All JSLE patients(n=480) | Pulmonary involvement*(n=119) | No-pulmonary involvement(n=361) | p-Value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male n (%) | 76 (16%) | 14 (12%) | 62 (17%) | 0.161 |

| Female n (%) | 404 (84%) | 105 (88%) | 299 (83%) | |

| Age at baseline in yearsMedian [IQR] | 12.9 [10.5–14.7] | 14.1 [11.6–14.9] | 12.7 [10.4–14.5] | 0.080 |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| British/Irish n (%) | 218 (45%) | 56 (47%) | 162 (45%) | 0.987 |

| Asian n (%) | 152 (32%) | 36 (30%) | 116 (32%) | |

| African/Caribbean n (%) | 77 (16%) | 19 (16%) | 58 (16%) | |

| Other Caucasians n (%) | 10 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Ethnicity not stated n (%) | 23 (5%) | 6 (5%) | 17 (5%) | |

Presence or absence of pulmonary manifestations (at any time between diagnosis and five years follow up) defined using data on pulmonary manifestations captured by either the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)-1997 classification criteria, and/or the pediatric version of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (pBILAG) score, and/or systemic lupus international collaborating clinics standardized damage index (SLICC-DI) score.

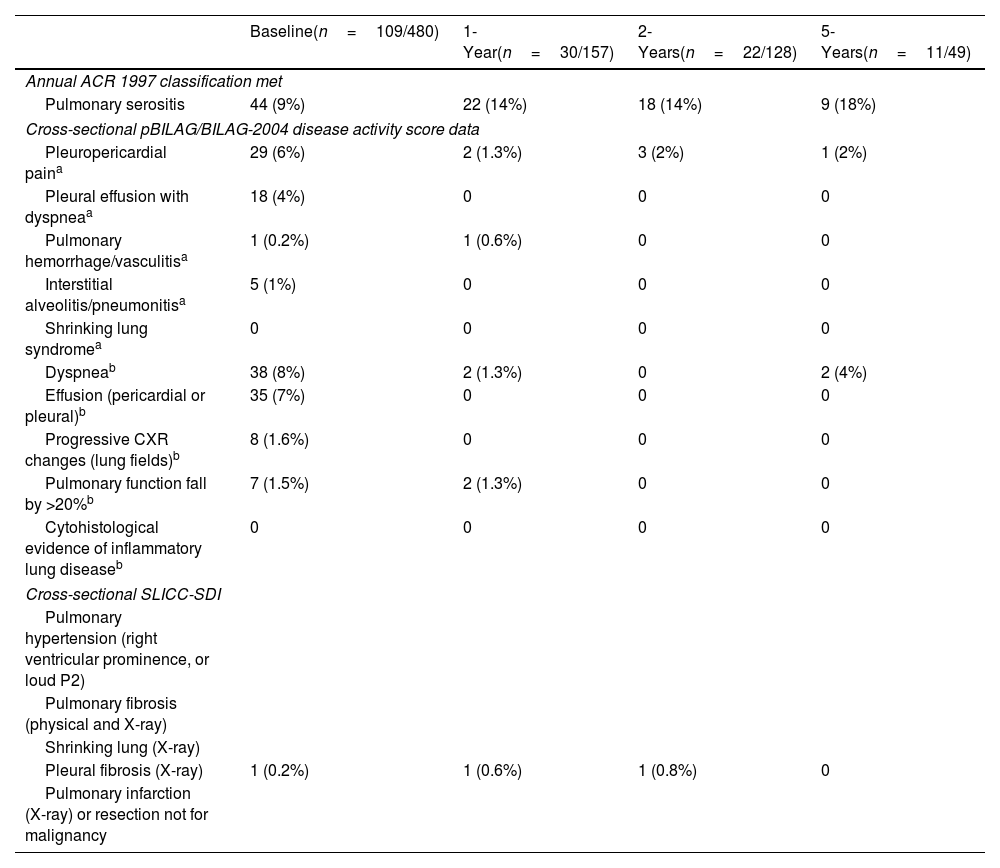

Overall, 119/480 (24.8%) patients had pulmonary manifestations at any time up to 5 years following baseline; 109/480 (22.7%) at diagnosis; 30/157 (19.1%) patients with available data at approximately 1 year, 22/128 (17.2%) patients at 2-years, and 11/49 (22.4%) patients at 5 years after baseline visit (see Table 2). Although most patients displayed pulmonary manifestations at baseline, at subsequent time points a small number of patients developed new pulmonary manifestations (six patients at 1 year, four at 2 years, and three at 5 years).

Pulmonary manifestations at diagnosis and during follow-up.

| Baseline(n=109/480) | 1-Year(n=30/157) | 2-Years(n=22/128) | 5-Years(n=11/49) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual ACR 1997 classification met | ||||

| Pulmonary serositis | 44 (9%) | 22 (14%) | 18 (14%) | 9 (18%) |

| Cross-sectional pBILAG/BILAG-2004 disease activity score data | ||||

| Pleuropericardial paina | 29 (6%) | 2 (1.3%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Pleural effusion with dyspneaa | 18 (4%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage/vasculitisa | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.6%) | 0 | 0 |

| Interstitial alveolitis/pneumonitisa | 5 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shrinking lung syndromea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspneab | 38 (8%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0 | 2 (4%) |

| Effusion (pericardial or pleural)b | 35 (7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Progressive CXR changes (lung fields)b | 8 (1.6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pulmonary function fall by >20%b | 7 (1.5%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0 | 0 |

| Cytohistological evidence of inflammatory lung diseaseb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cross-sectional SLICC-SDI | ||||

| Pulmonary hypertension (right ventricular prominence, or loud P2) | ||||

| Pulmonary fibrosis (physical and X-ray) | ||||

| Shrinking lung (X-ray) | ||||

| Pleural fibrosis (X-ray) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 |

| Pulmonary infarction (X-ray) or resection not for malignancy | ||||

Pulmonary manifestations included in the table were collected as part of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)-1997 classification criteria which are collected annually and reflect whether any new ACR features have occurred over the previous year. The pediatric version of the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (pBILAG) disease activity score and systemic lupus international collaborating clinics standardized damage index (SLICC-SDI) score were also used to describe pulmonary manifestations at baseline, 1, 2, and 5 years.

The types of pulmonary manifestation present at baseline and up to 5 years of follow-up are described in Table 2. Pulmonary serositis was the most common subtype of pulmonary involvement at baseline and during follow-up. Pulmonary hemorrhage/vasculitis, interstitial alveolitis/pneumonitis, and pleural fibrosis were seen rarely (≤1%), with shrinking lung syndrome and cytohistological evidence of inflammatory lung disease not recorded in any patients up to 5 years of follow-up. For some features collected by the BILAG (pleuropericardial pain, dyspnea, effusion (pericardial or pleural), it is impossible to determine if they are attributable to pulmonary, cardiac, or combined pulmonary/cardiac involvement. Pulmonary manifestations captured as part of the ACR-1997 classification criteria reflected whether any new ACR features have occurred over the previous year as these classification criteria are updated annually within the cohort. Pulmonary manifestations captured from the pBILAG and SLICC-SDI represent those present cross-sectionally at baseline, 1, 2, and 5 years (Table 2).

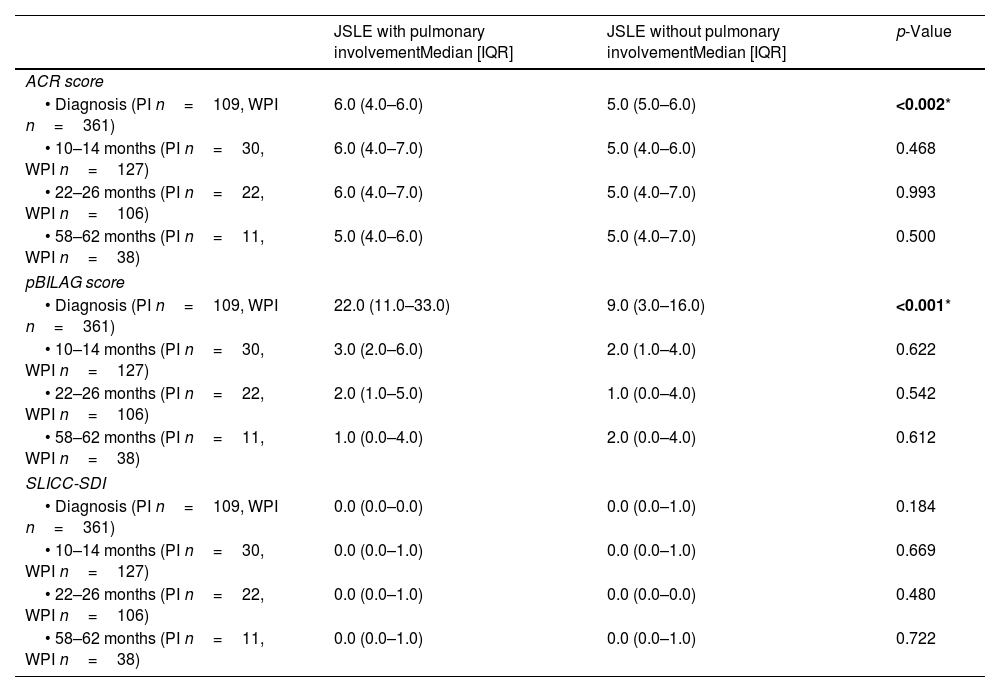

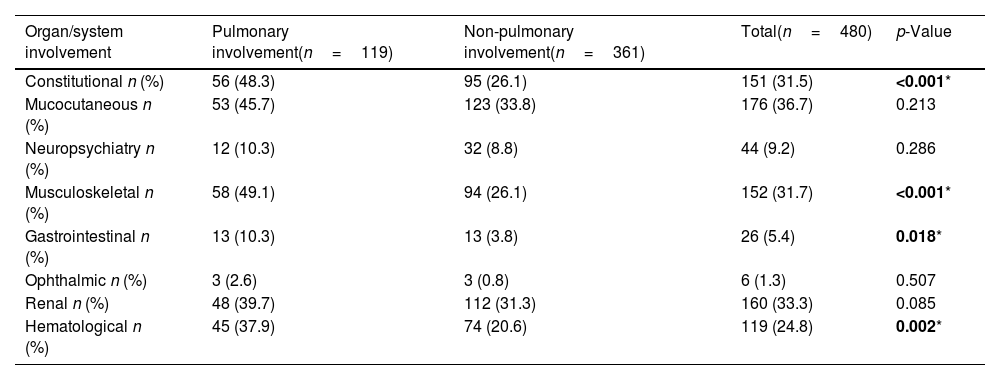

Classification criteria, disease activity, damage scores, and co-existing organ involvementPulmonary involvement was associated with higher ACR and pBILAG numerical disease activity scores at baseline (p<0.05), with no significant differences at the subsequent time points. There was no significant difference in SLICC damage scores at baseline or follow-up visits between those with or without pulmonary involvement. Constitutional, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal and hematological involvement were significantly more common in patients with pulmonary involvement (all p<0.05, Table 3). Of the 480 patients included in the study from diagnosis, 3/480 (0.006%) died during follow-up, none of which had displayed pulmonary involvement at baseline, 1, 2 or 5 years.

Classification criteria, disease activity, and organ damage in patients with/without pulmonary involvement.

| JSLE with pulmonary involvementMedian [IQR] | JSLE without pulmonary involvementMedian [IQR] | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACR score | |||

| • Diagnosis (PI n=109, WPI n=361) | 6.0 (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 (5.0–6.0) | <0.002* |

| • 10–14 months (PI n=30, WPI n=127) | 6.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 0.468 |

| • 22–26 months (PI n=22, WPI n=106) | 6.0 (4.0–7.0) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 0.993 |

| • 58–62 months (PI n=11, WPI n=38) | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 0.500 |

| pBILAG score | |||

| • Diagnosis (PI n=109, WPI n=361) | 22.0 (11.0–33.0) | 9.0 (3.0–16.0) | <0.001* |

| • 10–14 months (PI n=30, WPI n=127) | 3.0 (2.0–6.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 0.622 |

| • 22–26 months (PI n=22, WPI n=106) | 2.0 (1.0–5.0) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 0.542 |

| • 58–62 months (PI n=11, WPI n=38) | 1.0 (0.0–4.0) | 2.0 (0.0–4.0) | 0.612 |

| SLICC-SDI | |||

| • Diagnosis (PI n=109, WPI n=361) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.184 |

| • 10–14 months (PI n=30, WPI n=127) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.669 |

| • 22–26 months (PI n=22, WPI n=106) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.480 |

| • 58–62 months (PI n=11, WPI n=38) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.722 |

ACR: American College of Rheumatology, pBILAG: pediatric version of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group, SLICC: systemic lupus international collaborating clinics. Presence or absence of pulmonary manifestations defined using data on pulmonary manifestations captured by either the ACR-1997 classification criteria, and/or the pBILAG2004 score, and/or the SLICC-SDI score. PI: pulmonary involvement, WPI: without pulmonary involvement.

Constitutional, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal and hematological involvement were significantly more common in patients with pulmonary involvement (all p<0.05, Table 4). Of the 480 patients included in the study from baseline, 3/480 (0.006%) died during follow-up, none of which had displayed pulmonary involvement at baseline, 1, 2 or 5 years.

Co-existing BILAG-2004 defined organ domain involvement in patients with/without pulmonary involvement at diagnosis.

| Organ/system involvement | Pulmonary involvement(n=119) | Non-pulmonary involvement(n=361) | Total(n=480) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional n (%) | 56 (48.3) | 95 (26.1) | 151 (31.5) | <0.001* |

| Mucocutaneous n (%) | 53 (45.7) | 123 (33.8) | 176 (36.7) | 0.213 |

| Neuropsychiatry n (%) | 12 (10.3) | 32 (8.8) | 44 (9.2) | 0.286 |

| Musculoskeletal n (%) | 58 (49.1) | 94 (26.1) | 152 (31.7) | <0.001* |

| Gastrointestinal n (%) | 13 (10.3) | 13 (3.8) | 26 (5.4) | 0.018* |

| Ophthalmic n (%) | 3 (2.6) | 3 (0.8) | 6 (1.3) | 0.507 |

| Renal n (%) | 48 (39.7) | 112 (31.3) | 160 (33.3) | 0.085 |

| Hematological n (%) | 45 (37.9) | 74 (20.6) | 119 (24.8) | 0.002* |

This study is the largest to date describing pulmonary involvement and its associations with JSLE. The prevalence of pulmonary manifestation of 24.8% in this study was lower compared with the prevalence of 31% in Turkey,10 40–62% in Italy,17 and 83% in Oman.18 However, a study by Dai et al. reported a lower prevalence of 16.2%.19 The wide range of prevalence displayed by previous studies (16.2–83%) may be due to differences in patient demographics, sample size, different approaches in determining pulmonary involvement, and inconsistent screening for pulmonary involvement between countries/cohorts. Although slightly lower, the 24.8% prevalence of pulmonary disease in JSLE in the current study is comparable to the 28% reported by Beresford et al.20 in the UK and Moradinejad and Chitsaz21 in Iran. The prevalences from all previous reports10,17–21 indicate that pulmonary involvement in JSLE is a common manifestation, regardless of variations in study location, demographic characteristics, or sample size. This highlights the importance of routine pulmonary evaluation in JSLE management protocols. A UK-wide audit aimed at describing cardiopulmonary involvement in patients with four connective tissue diseases (JSLE, juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM), juvenile systemic sclerosis (JSSc)), highlighted that screening for cardiopulmonary involvement was inconsistent across the UK18 and that standards set by the Single Hub and Access Point for Paediatric Rheumatology in Europe (SHARE) recommendations19 and British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) guidelines,20 were largely not met. This may therefore lead to underrecognition of pulmonary involvement in JSLE, with the authors of the UK-wide audit concluding that multi-disciplinary team engagement is required to increase screening and improve long-term outcomes.18

The entire pulmonary system or any of its compartments can be independently or simultaneously affected by SLE, including airways, lung parenchyma, vasculature, pleura and respiratory musculature.5 The pulmonary manifestations in children include pleural effusion, lupus pneumonitis, interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hemorrhage and pulmonary fibrosis.17 The literature has demonstrated that the most common pulmonary involvement in SLE is serositis,5,16 in keeping with the findings of the current study.

Similar to findings of high BILAG-2004 disease activity score in patients with pulmonary involvement in the current study, pulmonary disease in adult SLE has been associated with high disease activity, identified through use of the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI).22,23 Patients with high disease activity may benefit from more comprehensive monitoring and early intervention.

The current study showed no association between pulmonary involvement and organ damage (SLICC-SDI), contrary to previous reports from the adult SLE population.23,24 This could have been due to differences in patients’ demographics, disease duration or healthcare access.

In our study, there was a significant association between constitutional, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and hematological manifestations and pulmonary involvement. This observation contrasts with the results of an Asian study describing pulmonary involvement in 111 children with JSLE, which found pericarditis and neuropsychiatric lupus to be the extra-pulmonary features associated with pulmonary involvement.16 Previous studies have not reported an association between pulmonary involvement in JSLE and the ACR-1997 score.16,17,25

Limitations of the studyThe current study comprehensively describes pulmonary involvement in JSLE at baseline, with later time points limited by much smaller patient numbers over time due to patients being early in their disease course, being transitioned to adult care, or lost to follow-up. It is unlikely that there is a direct association between pulmonary involvement at baseline and being lost to follow-up, with none of the patients who displayed pulmonary involvement at the study time points reported as having died during follow-up. The UK JSLE Cohort Study collects patient data alongside routine clinical care, rather than at exact time points. Therefore, data are reported at approximately 1 year, 2 years, and 5 years. The discrete cross-sectional follow-up time points assessed, do not allow us to comment on whether individual pulmonary manifestations present at diagnosis are persistent or recurrent within individual patients. The pBILAG captures a range of sub-types of pulmonary involvement. However, some of the reported features may also be due to pericarditis e.g. pleuropericardial pain, effusion (pericardial or pleural), and dyspnea, making it difficult to definitively report the prevalence of pulmonary involvement based on the data reported. As previously noted, cardiopulmonary screening is required to detect some types of pulmonary involvement described by the BILAG-2004 score (e.g. progressive CXR changes, pulmonary function fall by >20%, and shrinking lung syndrome). Considering these limitations, a prospective description of pulmonary involvement, linked to a structured cardiopulmonary screening plan is required to describe pulmonary involvement in JSLE more comprehensively. Also, this study does not describe the use of imaging studies and pulmonary function tests, laboratory parameters or autoantibodies, nor the treatment implemented for lung involvement. It does not report whether it was able to exclude those respiratory manifestations caused by an infection or another cause.

ConclusionPulmonary involvement is common in the UK JSLE Cohort, with the majority of cases present at diagnosis. The major sub-type of pulmonary involvement at diagnosis and subsequent follow up was serositis. Pulmonary involvement in JSLE is associated with significantly higher ACR-1997 and pBILAG scores, with significant co-involvement of the constitutional, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and hematological pBILAG-defined domains seen. Future prospective studies linked to a structured cardiopulmonary screening plan are required to provide more comprehensive knowledge of pulmonary involvement in JSLE, adding to the insights provided by the current study.

Authors’ contributionsEMDS, AF, and KM were responsible for the conception of the study. AF analyzed the data and interpreted the data with EMDS, KM, and MWB. All authors contributed substantially to the acquisition of patient data and assisted with interpretation of the results. AF drafted the initial manuscript and all authors have approved the submitted version of this manuscript.

Ethical approvalThe study has full ethical approvals in place (National Research Ethics Service North West, Liverpool, UK, reference 06/Q1502/77) and patient/parental consent or assent to participate in the study was obtained from all families.

FundingLupus UK provides financial support for the coordination of the UK JSLE Cohort Study [grant numbers: LUPUS UK: JXR10500, JXR12309]. The study took place as part of the UK's ‘Experimental Arthritis Treatment Centre for Children’ supported by Versus Arthritis [grant number ARUK-20621], the University of Liverpool, Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust, and the Alder Hey Charity, and based at the University of Liverpool and Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust. The funding bodies detailed above were not involved in the design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. AF was supported by a PRES/EMERGE clinical academic fellowship while undertaking this study for which she is thankful.

Conflict of interestNone.

The authors acknowledge all patients and their families who participated in this study. Specifically, the authors are grateful to all the support given by the entire multi-disciplinary team within each of the pediatric centers that are part of the UK JSLE Study Group (https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/translational-medicine/research/ukjsle/jsle/). The UK JSLE Cohort Study is supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (CRN): Children's National Specialty Group and CRN Research Nurses and staff in both UK centers, the NIHR Alder Hey Clinical Research Facility for Experimental Medicine, the UK's ‘Experimental Arthritis Treatment Center for Children’ (supported by Versus Arthritis, the University of Liverpool and Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust), and all those who have supported the work of the UK JSLE Study Group to date including especially LUPUS UK. Special recognition also goes to the Alder Hey Children's Hospital Clinical Academic Rheumatology team for hosting AF during a PRES/EMERGE clinical academic fellowship. Thanks also go to Carla Roberts for coordinating the UK JSLE Cohort Study.