Due to increasing improvement in the diagnosis, evaluation and management of osteoporosis and the development of new tools and drugs, the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) has promoted the development of recommendations based on the best evidence available. These recommendations should be a reference to rheumatologists and other health professionals involved in the treatment of patients with osteoporosis.

MethodsRecommendations were developed following a nominal group methodology and based on a systematic review. The level of evidence and the degree of recommendation were classified according to the model proposed by the Center for Evidence Based Medicine at Oxford. The level of agreement was established through Delphi technique. Evidence from previous consensus and available clinical guidelines was used.

ResultsWe have produced recommendations on diagnosis, evaluation and management of osteoporosis. These recommendations include the glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, premenopausal and male osteoporosis.

ConclusionsWe present the SER recommendations related to the biologic therapy risk management.

Dado el creciente avance en el diagnóstico como evaluación y tratamiento de la osteopososis, y la incorporación de nuevas herramientas y medicamentos, desde la Sociedad Española de Reumatología (SER) se ha impulsado el desarrollo de recomendaciones basadas en la mejor evidencia posible. Estas deben de servir de referencia para reumatólogos y otros profesionales de la salud implicados en el tratamiento de pacientes con osteoporosis.

MétodosLas recomendaciones se emitieron siguiendo la metodología de grupos nominales. El nivel de evidencia y el grado de recomendación se clasificaron según el modelo del Center for Evidence Based Medicine de Oxford y el grado de acuerdo se extrajo por técnica Delphi. Se utilizó toda la información de consensos previos y guías de práctica clínica disponibles.

ResultadosSe realizan recomendaciones sobre el diagnóstico, evaluación y tratamiento en pacientes con osteoporosis. Estas recomendaciones incluyen la osteopososis secundaria a glucocorticoides, la osteoporosis premenopáusica y la del varón.

ConclusionesSe presentan las recomendaciones SER sobre el diagnóstico, evaluación y manejo de pacientes con osteoporosis.

Updating knowledge on the different aspects of osteoporosis (OP) is still needed because of its high prevalence, its complications, and the associated health and social spending. At a time when the rational use of resources is important, this document is, in reality, a corporate reflection in which we analyze new evidence on diagnosis, risk factors for fracture, follow up and treatment of OP.

These recommendations are intended as a reference for therapeutic decision making to rheumatologists and all professionals who, from the different levels of care, are implicated in the treatment of OP.

MethodologyTasks were distributed for the elaboration of this document and commentary to each part. The structure of the document is based on questions relevant to clinical practice in OP.

Each panelist was first assigned one or several parts of the consensus for write up. Once completed, the whole panel was distributed for comment. After that, members of the research unit (RU) of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) unified, categorized, classified and summarized all of the comments for their evaluation prior to the panel getting together.

A meeting of the nominal group was carried out, moderated by members of the RU of SER. In this meeting, modification proposals in relation to format and content, including the recommendations, were performed.

Then, a Delphi survey was performed and consensus recommendations were voted on (anonymously online). The aggregated results were shown to all the panelists (modified Delphi). Recommendations with a degree of agreement (DA) of less than 70% were reedited and voted for a second time. Agreement is defined if, on a scale of 1 (complete disagreement) to 10 (complete agreement), the vote is 7 or more. The level of evidence (LE) and degree of recommendation (DR) are classified according to the model proposed by the Center for Evidence Based Medicine of Oxford1 by members of the RU of SER.

With all of this information the definite document was written up.

ResultsDiagnosis and EvaluationWhat Is Osteoporosis?OP has been defined in the consensus conference of the National Institute of Health as a skeletal disease characterized by reduced bone resistance that predisposes an increase in the risk of fracture (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

Bone resistance reflects the integration of bone density and bone quality. At the same time, bone density is determined by the peak value of bone mass and the magnitude of its loss, while bone quality depends on architecture, bone exchange, the accumulation of microlesions and mineralization.2

When Should I Suspect a Case of Osteoporosis?There is no current population survey protocol that is universally accepted for the identification of persons with OP. Patients are identified by a strategy of case by case search based on a history of one or more fragility associated fractures or the presence of significant clinical risk factors.3

In certain groups of patients, mainly the elderly and postmenopausal women, we must maintain a high degree of suspicion and actively search for risk factors (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

What Is Considered an Osteoporotic Fracture?An osteoporotic fracture or fragility fracture is conditioned by low impact trauma. A fall from a standing or sitting position is included in this concept. Fractures that occur as a consequence of sports or accidents are excluded (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

It is estimated that close to 40% of Caucasian women will have at least one fracture after the age of 50.4–9 The most frequent and relevant are those of the proximal femur, the spinal column and the distal forearm. On the other hand, we must point out that fractures of the cranium or face are excluded from this definition.10

What Is High Risk of Osteoporotic Fracture?As occurs with OP, there is no universally accepted survey to identify the population with a high risk of fracture.

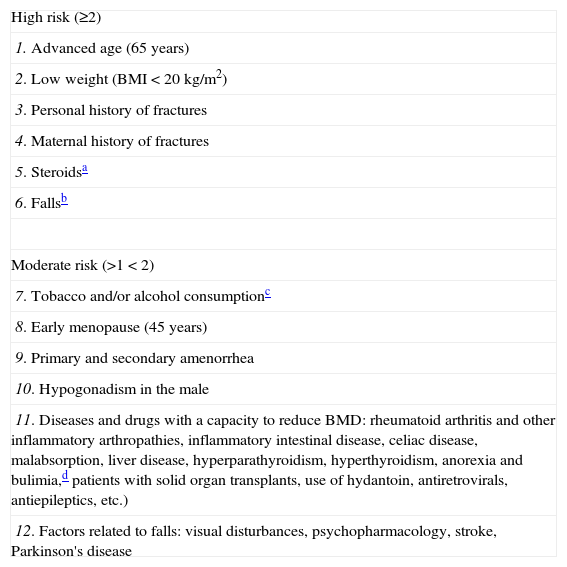

The risk of osteoporotic fracture is determined by the presence of one or more risk factors including low bone mineral density (BMD). The combination of risk conferred by a low BMD with clinical risk factors11 allows for a better estimate of risk. We consider a high risk for fracture when there are at least 2 high risk factors (Table 1). Having a tool for the calculation of osteoporotic fracture risk would permit the identification of persons with a high risk who would merit early intervention and reduce the number of unnecessary treatments administered to low risk patients.

Risk Factors for Fracture.

| High risk (≥2) |

| 1. Advanced age (65 years) |

| 2. Low weight (BMI<20kg/m2) |

| 3. Personal history of fractures |

| 4. Maternal history of fractures |

| 5. Steroidsa |

| 6. Fallsb |

| Moderate risk (>1<2) |

| 7. Tobacco and/or alcohol consumptionc |

| 8. Early menopause (45 years) |

| 9. Primary and secondary amenorrhea |

| 10. Hypogonadism in the male |

| 11. Diseases and drugs with a capacity to reduce BMD: rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthropathies, inflammatory intestinal disease, celiac disease, malabsorption, liver disease, hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, anorexia and bulimia,d patients with solid organ transplants, use of hydantoin, antiretrovirals, antiepileptics, etc.) |

| 12. Factors related to falls: visual disturbances, psychopharmacology, stroke, Parkinson's disease |

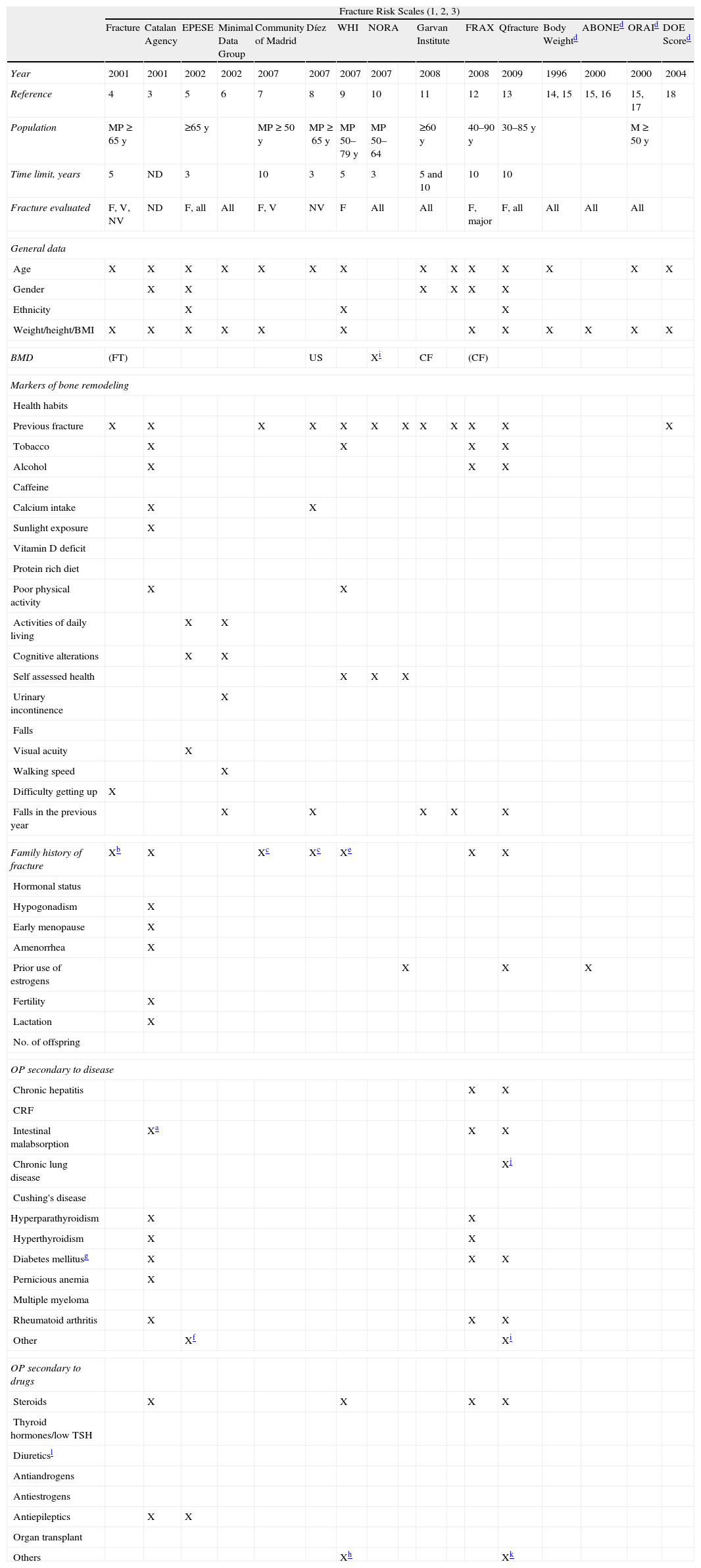

Different instruments that estimate the risk of fracture based on risk factors have been developed (Table 2). Of them, the most important is the FRAX tool©, a software tool sponsored by the WHO,12 which can be applied with and without BMD. The FRAX® algorithms calculate the absolute 10 year probability of fracture into a group of “major fractures” (clinical vertebral, forearm, hip and humeral fractures) and isolated hip fractures. It is currently the most recommended instrument used to calculate the risk of osteoporotic fracture. However, as everything, it has limitations and the medical judgment of the clinician is still fundamental. The risk of a major fracture calculated by FRAX© in the Spanish population over 15% is very specific for osteoporosis.

Characteristics of the Different Scales Evaluating Risk of Osteoporotic Fracture.

| Fracture Risk Scales (1, 2, 3) | |||||||||||||||||

| Fracture | Catalan Agency | EPESE | Minimal Data Group | Community of Madrid | Díez | WHI | NORA | Garvan Institute | FRAX | Qfracture | Body Weightd | ABONEd | ORAId | DOE Scored | |||

| Year | 2001 | 2001 | 2002 | 2002 | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | 2008 | 2008 | 2009 | 1996 | 2000 | 2000 | 2004 | ||

| Reference | 4 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14, 15 | 15, 16 | 15, 17 | 18 | ||

| Population | MP≥65 y | ≥65 y | MP≥50 y | MP≥65 y | MP 50–79 y | MP 50–64 | ≥60 y | 40–90 y | 30–85 y | M≥50 y | |||||||

| Time limit, years | 5 | ND | 3 | 10 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 and 10 | 10 | 10 | |||||||

| Fracture evaluated | F, V, NV | ND | F, all | All | F, V | NV | F | All | All | F, major | F, all | All | All | All | |||

| General data | |||||||||||||||||

| Age | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Gender | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Ethnicity | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Weight/height/BMI | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| BMD | (FT) | US | Xi | CF | (CF) | ||||||||||||

| Markers of bone remodeling | |||||||||||||||||

| Health habits | |||||||||||||||||

| Previous fracture | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Tobacco | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Alcohol | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Caffeine | |||||||||||||||||

| Calcium intake | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Sunlight exposure | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Vitamin D deficit | |||||||||||||||||

| Protein rich diet | |||||||||||||||||

| Poor physical activity | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Activities of daily living | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Cognitive alterations | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Self assessed health | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Urinary incontinence | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Falls | |||||||||||||||||

| Visual acuity | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Walking speed | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Difficulty getting up | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Falls in the previous year | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Family history of fracture | Xb | X | Xc | Xc | Xe | X | X | ||||||||||

| Hormonal status | |||||||||||||||||

| Hypogonadism | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Early menopause | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Amenorrhea | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Prior use of estrogens | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Fertility | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Lactation | X | ||||||||||||||||

| No. of offspring | |||||||||||||||||

| OP secondary to disease | |||||||||||||||||

| Chronic hepatitis | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| CRF | |||||||||||||||||

| Intestinal malabsorption | Xa | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Chronic lung disease | Xj | ||||||||||||||||

| Cushing's disease | |||||||||||||||||

| Hyperparathyroidism | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Hyperthyroidism | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Diabetes mellitusg | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Pernicious anemia | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Multiple myeloma | |||||||||||||||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Other | Xf | Xi | |||||||||||||||

| OP secondary to drugs | |||||||||||||||||

| Steroids | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Thyroid hormones/low TSH | |||||||||||||||||

| Diureticsl | |||||||||||||||||

| Antiandrogens | |||||||||||||||||

| Antiestrogens | |||||||||||||||||

| Antiepileptics | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Organ transplant | |||||||||||||||||

| Others | Xh | Xk | |||||||||||||||

CF: Femoral neck; DMO: Bone densitometry; F: femoral fracture; FT: total femur; FV: vertebral fracture; H: humeral fracture; CRF: chronic renal failure; MP: postmenopausal women; ND: no defined/no determined; NV: non-vertebral fracture; OP: osteoporosis; R: fracture of the distal third of the radius; US: ultrasound.

There is no consensus in the medical literature on the threshold above which the risk for a fracture would be considered “high” in the Spanish population. An approximation would be:

- –

Absolute 10 year risk of fracture <10%: low.

- –

Absolute 10 year risk of fracture ≥10% and <20%: moderate.

- –

Absolute 10 year risk of fracture ≥20%: low.

If FRAX© is employed, its systemic application is recommended in patients in whom: (a) the indication of a BMD is being evaluated; (b) the onset of treatment is being evaluated for OP, and (c) they are over 65 years of age.

What History and Examination Data Are Important?If OP is suspected, with the aim of evaluating the risk of fracture and the cause of OP, we recommend obtaining the following data: age, ethnicity, history of toxic habits (tobacco, alcohol), dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D, degree of exposure to sunlight, menstrual history (age at menopause and menarche), obstetric history (interventions, surgical menopause, hypogonadism), osteopenia associated diseases and drugs, previous trauma, family or personal history of fragility fractures and conditions associated to falls, as well as data regarding recent or prior fractures (LE 5; DR D; DA 95%).

The presence of present or prior fractures should be evaluated determining episodes of acute and/or chronic back pain, progressive reduction in height, etc.13,14 It is important to remember that OP is asymptomatic and that more than half of the vertebral fractures are also asymptomatic.15

It is recommended that physical examination record weight, height, the existence of skeletal deformities and palpation/percussion of the spine be carried out (LE 5; DR D; DA 90%).

The relationship between the body mass index and BMD is well known.16 The possible existence of skeletal deformities should be established by the presence of dorsal kyphosis, a reduction of the space between the ribs and the pelvis, etc., and palpation/percussion should be directed to the localization of painful zones of the locomotor system.14 General physical examination may provide data on other diseases associated to a reduction in bone mass.

What Laboratory Data Is Important?Laboratory tests are performed to identify associated processes and perform a differential diagnosis with other diseases associated to bone fragility.17–21

When OP is suspected, one should request: complete blood count, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, serum proteins, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum calcium and phosphorus and 24h urinary calcium excretion (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

It is advisable to determine during the initial visit what the levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25-[OH]-D3), parathyroid hormone (PTH) and thyroid stimulating hormone are (LE 5; DR D; DA 80%).

In case an associated disease is suspected, pertinent laboratory tests should be performed (LE 5; DR D; DA 95%).

The systematic determination of bone markers is not recommended for the diagnosis and evaluation of patients with OP. Their measurement is useful to identify subjects with a greater risk of fracture and especially to evaluate in an early manner response to, both antiresorptive as well as bone forming treatments (LE 2c; DR C; DA 80%).

Bone remodeling markers provide additional and complementary information to the study of BMD. Osteocalcin, bone alkaline phosphatase and type I procollagen aminoterminal propeptide stand out as bone formation markers and pyridinolynes, carboxy and aminoterminal telopeptides of type I collagen (serum CTX and urine NTX) and tartrate 5b resistant acid phosphatase stand out among those associated to resorption. These are more sensitive and specific than classic markers such as total alkaline phosphatase and hydroxyproline. It is important to take into account biological variability and circadian rhythm in their correct interpretation and therefore establish an adequate schedule to obtain samples.22–24

When Is it Advisable to Request Spinal X-rays?Spine radiographs are not useful to assess the decrease in BMD, but allow the diagnosis of fractures, including asymptomatic ones. We must remember that the presence of prior vertebral fracture is a significant risk factor for new fractures, both vertebral and non-vertebral.25–29

In patients with suspected or diagnosed OP, it is recommended to perform an initial spinal X-ray for detecting fractures (LE 2b; DR B; DA 95%).

If there is suspicion of vertebral fracture during follow up, a spinal X-ray is recommended (LE 2b; DR B; DA 100%).

The panel believes that for the diagnosis of spinal fractures, lateral, dorsal and lumbar spine X-rays, with focus on D8 and L2, respectively30 are sufficient (LE 2a; DR C; DA 100%).

Anteroposterior projections are not essential for diagnosis but can provide additional information.

When Is it Indicated to Perform a Bone Densitometry?A densitometric survey of the general population is not cost-effective31 and there is great variability regarding indications for densitometry.3,32–37 Until today there are no validated tools that satisfactorily quantify the risk of fracture or a consensus on the definition of risk of fracture that helps determine a therapeutic intervention. The evaluation of BMD along with other risk factorsis useful for the diagnosis and follow up of patients.

The indication for performing a densitometry should be based on clinical criteria that allow the selection of patients in which the use of this technology is efficient (LE 2b; DR B; DA 95%).

Before requesting for it is essential to be certain that the result will help determine the therapeutic decision to be taken.38

A baseline densitometry is recommended in the following (LE 5; DR D; DA 75%):

- 1.

Women with early menopause and any major risk factors for fracture.

- 2.

Postmenopausal women of any age and men over 50 with at least one major risk factor for fracture.

- 3.

A history of fragility fracture in patients over 50.

- 4.

Underlying disease or chronic treatment with medication associated to bone loss, especially glucocorticoids.

- 5.

Women over 65 years of age and men >70 without known risk factors at least in one occasion if patient request it.

- 6.

Evaluation of pharmacologic treatment.

- 7.

If the FRAX© is employed, a densitometry is recommended in women 65 and older and those younger but with a major risk factor for fracture according to the FRAX©, equivalent to a 65 year old woman with no risk factors de riesgo (Spanish FRAX 3.6%).39,40

To detect significant changes with a confidence interval (CI) of 95%, these should be, at least, 2.8 times the variation coefficient (minimum significant change). In clinical practice its application is difficult because very strict precision measures are needed.41 The use of another concept is more practical, “the smallest detectable difference” which is established in 2% (change in lumbar BMD±0.05g/cm2, total femur±0.04g/cm2).42 Although major changes in BMD are detected on the lumbar spine, it is also useful to monitor the hip because it is less dependent on artifacts produced by degenerative change.

Which Densitometric Technique Is the Most Adequate?Dual energy X-ray absorciometry (DXA) is recommended as the reference technique for measuring BMD (LE 2b; DR B; DA 100%).

DXA is a technique that has good precision, low radiological exposure and allows for measurement of BMD both in the axial as well as in the peripheral skeleton. It is considered the best technique to evaluate BMD.28,41,42

What Is Dual Energy X-ray Absorciometry Good for?Results of BMD obtained through DXA predict the future risk of fracture due to OP, both in postmenopausal women as in elderly males.43–49 But in addition, according to WHO, to diagnose OP it is necessary to know the value of the BMD in the femur and lumbar spine through a central DXA.50,51 Currently, central DXA is the only validated technique to follow up and for evaluation of therapeutic response.

To perform a diagnosis of OP, we recommend carrying out a DXA, as long as it is possible on the hip and lumbar spine (LE 2b; DR B; DA 95%).

A lateral projection of the spine should not be used for the diagnosis of OP.

If DXA of the lumbar spine or hip is impossible, it is recommended that DXA be performed on the distal third of the radius of the non-dominating forearm (LE 2b; DR B; DA 90%).

This may occur in case of anatomical alterations (scoliosis, degenerative problems, multiple vertebral fractures, morbid obesity) or technical problems (presence of metallic elements after spinal surgery, hip arthroplasty).52

When necessary, control DXA of the hip and the spine should be performed with the same equipment (LE 1b; DR A; DA 90%).

Long-term precision or reproducibility of DXA; expressed as a variation coefficient, varies according to the measurement area and the equipment used from 1 to 2%.53–55 In women undergoing treatment for postmenopausal OP, densitometric controls should be performed every 2–3 years.32 In general, codensitometric controls are not recommended before 2 years because it has been seen that some patients who lose bone mass during the first year may regain it during the second.55

Ultrasound, peripheral DXA equipment and central or peripheral quantitative computerized tomography are useful to predict an elevated risk of fracture but should not be used for diagnosis, follow up or evaluation of therapeutic response in patients with OP (LE 1a; DR A; DA 95%).

There are other techniques to measure BMD in the peripheral skeleton, such as phalangeal, knee and calcaneus DXA, and calcaneus ultrasound. They are cheaper, easier to handle and faster in comparison to central DXA but, among other limitations, their precision is low.49,52,56,57 They are useful to predict the future risk of fracture and may have some value when it is impossible to perform a central DXA.49,52,56 Peripheral quantitative computed tomography is a rapidly developing imaging technique. It allows for volumetric BMD measurement of the lumbar spine, hip and distal radiums, but its results are not comparable to those obtained through DXA.58

How Is Osteoporosis Diagnosed?Diagnosis of OP is based on the densitometric criteria established by WHO for white postmenopausal women (BMD values under −2.5 standard deviations (SD) (T-score inferior to −2.5) and/or the presence of fragility fractures (LE 2c; DR B; DA 90%).

Cutpoints for BMD measured by DXA on the lumbar spine and hip59–61 correspond to normal, values of BMD>−1 SD in relation with the mean of young adults (T-score>−1); osteopenia or low bone mass, BMD values between −1 and −2.5 SD (T-score between −1 and −2.5); OP, BMD values of <−2.5 DE (T-score<−2.5), and established OP when the previous condition is associated to ≥1 osteoporotic fracture. The same cutpoints have been proposed for adult males.60

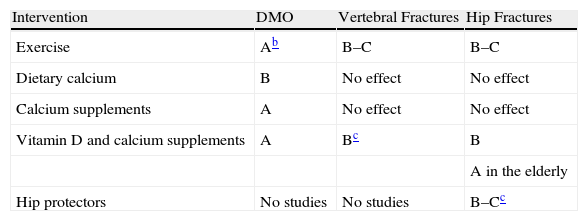

TreatmentWhat Non-pharmacologic Methods Should we Use?The following general measures should be recommended to all of the population, with special emphasis on osteoporotic patients: physical exercise, elimination of toxic habits, balanced diet, adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, preventing falls (LE 1a; DR A; DA 100%).

Moderate to intense physical exercise increases bone mass in young patients,62–66 as well as in adults, although less intensely.67 There is no consistent evidence on the effect over bone mass in elderly patients, but performing it reduces the risk of fractures, probably by reducing falls.68–70

Avoidance of sedentarism and the performance of moderate physical activity are recommended, taking into account the patients’ age, physical status and other diseases (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

A balanced diet with an adequate consumption of proteins, avoidance of excess salt and moderate sun exposure are also recommended (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

A daily calcium intake of 1000mg and serum 25-OH vitamin D levels of ≥30ng/ml (75mmol/l) is recommended (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

Sometimes, common diets do not provide these calcium requirements and therefore must be modified or supplemented with pharmacological calcium which, if taken isolatedly, has not shown a significant effect on the reduction of fractures in postmenopausal OP, but help reduce the loss of bone mass.71–73 In healthy women it has been suggested to increase cardiovascular risk74,75 and renal litiasis,76 but this is a controversial and unclear subject.

Approximately 50% of the osteoporotic population presents low serum concentrations of vitamin D and it is advisable to supplement it with 800–1000U in all patients. The efficacy of vitamin D supplements in the prevention of fractures is controversial.77–82 There is evidence that it reduces fractures in institutionalized elderly patients when administered with calcium.77–82 Additionally, some studies indicate that vitamin D supplements may reduce falls81 but other do not.82

In patients receiving anticatabolic treatment, we recommend an intake of 1000mg of calcium and 800–1000U of vitamin D is recommended (LE 1a; DR A; DA 95%).

In the elderly, measures directed at reducing the risk of falls, promoting the use of canes, avoiding psychopharmacologic agents, correcting visual disturbances and adapting living spaces are recommended. In high risk populations, hip protectors may be employed.83–85

For more information consult Table 3.

Degree of Recommendation of Non-pharmacologic Interventions.a

| Intervention | DMO | Vertebral Fractures | Hip Fractures |

| Exercise | Ab | B–C | B–C |

| Dietary calcium | B | No effect | No effect |

| Calcium supplements | A | No effect | No effect |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplements | A | Bc | B |

| A in the elderly | |||

| Hip protectors | No studies | No studies | B–Cc |

BMD: Bone.

The goals of treatment of a vertebral fracture are acute pain control and functional recovery (LE 2b; DR B; DA 100%).

It is very important to inform patients that fractures may take up to 3 months to consolidate and that pain will gradually decrease and improve function.86

Oral analgesics, relative rest, orthoses and rehabilitation are the mainstays of treatment (LE 2b; DR B; DA 90%).

Oral analgesics are first-line drugs to reduce the pain of vertebral fractures. The choice should be appropriate to the magnitude of pain. In cases where the pain reaches a significant intensity and conventional painkillers failed, we recommend using opioids.87,88

If complete rest is indicated, return to sitting and walking should be accomplished in the shortest possible time. During the acute episode there may be a need for prescription orthotics and, once control of acute pain is achieved, rehabilitation may be useful (LE 5; DR B; DA 95%).

A back brace should be used with caution as excessive spinal immobility could increase OP,89 and rehabilitation should be directed by a specialist.90

In patients with acute vertebral fractures with pain that does not respond to the above measures, vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty may be indicated (LE 1c; DR B; DA 95%).

Several observational studies have shown rapid analgesic effect and reduced period of immobilization in a high percentage of patients, in the short to medium term, but this does not exempt these procedures from secondary.91–96 Recently, two controlled clinical trials have not shown that vertebroplasty was more effective than other conservative options.97,98 Another controlled trial has found benefit with the use of vertebroplasty in a subgroup of patients with persistent intense symptoms.99 Based on the above, patients who are going to undergo these interventions should be carefully selected.100

Currently, no generalization can be recommended for vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty to treat osteoporotic vertebral fractures (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

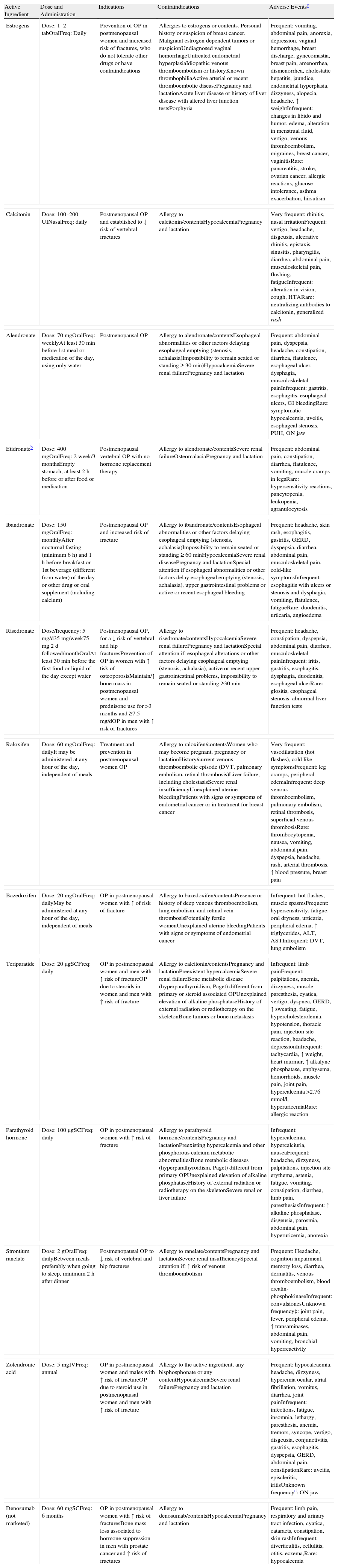

What Drugs Should Be Recommended in Osteoporosis?The objective of pharmacologic treatment of OP is to reduce the risk of fracture (LE 1a; DR A; DA 100%).

Pharmacological intervention is performed with therapeutic agents capable of acting in both phases of bone remodeling. At present, there are three categories of anti-osteoporotic drugs, antiresorptive and anti-catabolic, which inhibit bone resorption by acting on osteoclasts and their precursors, decrease the rate of activation of bone remodeling, increase bone mineral density and preserve the microarchitecture of the bone; and anabolic drugs, which act on osteoblasts or their precursors resulting in increased bone remodeling, with bone formation increased to a greater extent than resorption, which in time increases mass and bone strength, as well as agents with a double mechanism of action where there is a combination of both.101,102

For more information regarding their indications, efficacy in relation to the prevention of fractures and adverse events, see Tables 4 and 5.

Characteristics of the Main Drugs Commercialized for Osteoporosis in Spain (According to the Data Sheet, Current to January 2010).a

| Active Ingredient | Dose and Administration | Indications | Contraindications | Adverse Eventsc |

| Estrogens | Dose: 1–2 tabOralFreq: Daily | Prevention of OP in postmenopausal women and increased risk of fractures, who do not tolerate other drugs or have contraindications | Allergies to estrogens or contents. Personal history or suspicion of breast cancer. Malignant estrogen dependent tumors or suspicionUndiagnosed vaginal hemorrhageUntreated endometrial hyperplasiaIdiopathic venous thromboembolism or historyKnown thrombophiliaActive arterial or recent thromboembolic diseasePregnancy and lactationAcute liver disease or history of liver disease with altered liver function testsPorphyria | Frequent: vomiting, abdominal pain, anorexia, depression, vaginal hemorrhage, breast discharge, gynecomastia, breast pain, amenorrhea, dismenorrhea, cholestatic hepatitis, jaundice, endometrial hyperplasia, dizzyness, alopecia, headache, ↑ weightInfrequent: changes in libido and humor, edema, alteration in menstrual fluid, vertigo, venous thromboembolism, migraines, breast cancer, vaginitisRare: pancreatitis, stroke, ovarian cancer, allergic reactions, glucose intolerance, asthma exacerbation, hirsutism |

| Calcitonin | Dose: 100–200 UINasalFreq: daily | Postmenopausal OP and established to ↓ risk of vertebral fractures | Allergy to calcitonin/contentsHypocalcemiaPregnancy and lactation | Very frequent: rhinitis, nasal irritationFrequent: vertigo, headache, disgeusia, ulcerative rhinitis, epistaxis, sinusitis, pharyngitis, diarrhea, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, flushing, fatigueInfrequent: alteration in vision, cough, HTARare: neutralizing antibodies to calcitonin, generalized rash |

| Alendronate | Dose: 70mgOralFreq: weeklyAt least 30min before 1st meal or medication of the day, using only water | Postmenopausal OP | Allergy to alendronate/contentsEsophageal abnormalities or other factors delaying esophageal emptying (stenosis, achalasia)Impossibility to remain seated or standing≥30min)HypocalcemiaSevere renal failurePregnancy and lactation | Frequent: abdominal pain, dyspepsia, headache, constipation, diarrhea, flatulence, esophageal ulcer, dysphagia, musculoskeletal painInfrequent: gastritis, esophagitis, esophageal ulcers, GI bleedingRare: symptomatic hypocalcemia, uveitis, esophageal stenosis, PUH, ON jaw |

| Etidronateb | Dose: 400mgOralFreq: 2 week/3 monthsEmpty stomach, at least 2h before or after food or medication | Postmenopausal vertebral OP with no hormone replacement therapy | Allergy to alendronate/contentsSevere renal failureOsteomalaciaPregnancy and lactation | Frequent: abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, flatulence, vomiting, muscle cramps in legsRare: hypersensitivity reactions, pancytopenia, leukopenia, agranulocytosis |

| Ibandronate | Dose: 150mgOralFreq: monthlyAfter nocturnal fasting (minimum 6h) and 1h before breakfast or 1st beverage (different from water) of the day or other drug or oral supplement (including calcium) | Postmenopausal OP and increased risk of fracture | Allergy to ibandronate/contentsEsophageal abnormalities or other factors delaying esophageal emptying (stenosis, achalasia)Impossibility to remain seated or standing≥60minHypocalcemiaSevere renal diseasePregnancy and lactationSpecial attention if esophageal abnormalities or other factors delay esophageal emptying (stenosis, achalasia), upper gastrointestinal problems or active or recent esophageal bleeding | Frequent: headache, skin rash, esophagitis, gastritis, GERD, dyspepsia, diarrhea, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, cold-like symptomsInfrequent: esophagitis with ulcers or stenosis and dysphagia, vomiting, flatulence, fatigueRare: duodenitis, urticaria, angioedema |

| Risedronate | Dose/frequency: 5mg/d35mg/week75mg 2 d followed/monthOralAt least 30min before the first food or liquid of the day except water | Postmenopausal OP, for a ↓ risk of vertebral and hip fracturesPrevention of OP in women with ↑ tisk of osteoporosisMaintain/↑ bone mass in postmenopausal women and prednisone use for >3 months and ≥7.5mg/dOP in men with ↑ risk of fractures | Allergy to risedronate/contentsHypocalcemiaSevere renal failurePregnancy and lactationSpecial attention if: esophageal alterations or other factors delaying esophageal emptying (stenosis, achalasia), active or recent upper gastrointestinal problems, impossibility to remain seated or standing ≥30min | Frequent: headache, constipation, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, musculoskeletal painInfrequent: iritis, gastritis, esophagitis, dysphagia, duodenitis, esophageal ulcerRare: glositis, esophageal stenosis, abnormal liver function tests |

| Raloxifen | Dose: 60mgOralFreq: dailyIt may be administered at any hour of the day, independent of meals | Treatment and prevention in postmenopausal women OP | Allergy to raloxifen/contentsWomen who may become pregnant, pregnancy or lactationHistory/current venous thromboembolic episode (DVT, pulmonary embolism, retinal thrombosis)Liver failure, including cholestasisSevere renal insufficiencyUnexplained uterine bleedingPatients with signs or symptoms of endometrial cancer or in treatment for breast cancer | Very frequent: vasodilatation (hot flashes), cold like symptomsFrequent: leg cramps, peripheral edemaInfrequent: deep venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, retinal thrombosis, superficial venous thrombosisRare: thrombocytopenia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, headache, rash, arterial thrombosis, ↑ blood pressure, breast pain |

| Bazedoxifen | Dose: 20mgOralFreq: dailyMay be administered at any hour of the day, independent of meals | OP in postmenopausal women with ↑ of risk of fracture | Allergy to bazedoxifen/contentsPresence or history of deep venous thromboembolism, lung embolism, and retinal vein thrombosisPotentially fertile womenUnexplained uterine bleedingPatients with signs or symptoms of endometrial cancer | Infrequent: hot flashes, muscle spasmsFrequent: hypersensitivity, fatigue, oral dryness, urticaria, peripheral edema, ↑ triglycerides, ALT, ASTInfrequent: DVT, lung embolism |

| Teriparatide | Dose: 20μgSCFreq: daily | OP in postmenopausal women and men with ↑ risk of fractureOP due to steroids in women and men with ↑ risk of fracture | Allergy to calcitonin/contentsPregnancy and lactationPreexistent hypercalcemiaSevere renal failureBone metabolic disease (hyperparathyroidism, Paget) different from primary or steroid associated OPUnexplained elevation of alkaline phosphataseHistory of external radiation or radiotherapy on the skeletonBone tumors or bone metastasis | Infrequent: limb painFrequent: palpitations, anemia, dizzyness, muscle paresthesia, cyatica, vertigo, dyspnea, GERD, ↑ sweating, fatigue, hypercholesterolemia, hypotension, thoracic pain, injection site reaction, headache, depressionInfrequent: tachycardia, ↑ weight, heart murmur, ↑ alkalyne phosphatase, enphysema, hemorrhoids, muscle pain, joint pain, hypercalcemia >2.76mmol/l, hyperuricemiaRare: allergic reaction |

| Parathyroid hormone | Dose: 100μgSCFreq: daily | OP in postmenopausal women with ↑ risk of fracture | Allergy to parathyroid hormone/contentsPregnancy and lactationPreexisting hypercalcemia and other phosphorous calcium metabolic abnormalitiesBone metabolic diseases (hyperparathyroidism, Paget) different from primary OPUnexplained elevation of alkaline phosphataseHistory of external radiation or radiotherapy on the skeletonSevere renal or liver failure | Infrequent: hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, nauseaFrequent: headache, dizzyness, palpitations, injection site erythema, astenia, fatigue, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, limb pain, paresthesiasInfrequent: ↑ alkaline phosphatase, disgeusia, parosmia, abdominal pain, hyperuricemia, anorexia |

| Strontium ranelate | Dose: 2gOralFreq: dailyBetween meals preferably when going to sleep, minimum 2h after dinner | Postmenopausal OP to ↓ risk of vertebral and hip fractures | Allergy to ranelate/contentsPregnancy and lactationSevere renal insufficiencySpecial attention if: ↑ risk of venous thromboembolism | Frequent: Headache, cognition impairment, memory loss, diarrhea, dermatitis, venous thromboembolism, blood creatin-phosphokinaseInfrequent: convulsionesUnknown frequency‡: joint pain, fever, peripheral edema, ↑ transaminases, abdominal pain, vomiting, bronchial hyperreactivity |

| Zolendronic acid | Dose: 5mgIVFreq: annual | OP in postmenopausal women and males with ↑ risk of fractureOP due to steroid use in postmenopausal women and men with ↑ risk of fracture | Allergy to the active ingredient, any bisphosphonate or any contentHypocalcemiaSevere renal failurePregnancy and lactation | Frequent: hypocalcaemia, headache, dizzyness, hyperemia ocular, atrial fibrillation, vomitus, diarrhea, joint painInfrequent: infections, fatigue, insomnia, lethargy, paresthesia, anemia, tremors, syncope, vertigo, disgeusia, conjunctivitis, gastritis, esophagitis, dyspepsia, GERD, abdominal pain, constipationRare: uveitis, episcleritis, iritisUnknown frequencyd: ON jaw |

| Denosumab (not marketed) | Dose: 60mgSCFreq: 6 months | OP in postmenopausal women with ↑ risk of fracturesBone mass loss associated to hormone suppression in men with prostate cancer and ↑ risk of fractures | Allergy to denosumab/contentsHypocalcemiaPregnancy and lactation | Frequent: limb pain, respiratory and urinary tract infection, cyatica, cataracts, constipation, skin rashInfrequent: diverticulitis, cellulitis, otitis, eczema,Rare: hypocalcemia |

Tab: tablets; Freq: frequency; HTA: arterial hypertension; iv: intravenous; mg: milligram; μg: microgram; w: weekly; ON: osteonecrosis; OP: osteoporosis; PUH: perforation, ulcers, hemorrhage; GER: gastroesophageal reflux; sc: subcutaneous; DVT: deep venous thrombosis.

Antifracture Efficacy of Antiosteoporotic Drugs.

| Study | Population | Intervention | % FV PLC | % FV INT | RR (CI 95%) | RRR | RAR | NNT |

| Morphometric vertebral fracture | ||||||||

| Black et al.,a 1996, CT double blind placebo controlled, 3 years | n=2027 ♀ with ↓ BMD and ≥1 FV | Aln=5mg/day→10mg/day | 15% | 8% | 0.53 (0.40–0.68) | 47% | 7% | 14 |

| Cummings et al.,b 1998, CT double blind placebo controlled, 4 years | n=4432 ♀ with ↓ BMD no FV | Aln=5mg/day→10mg/d | 14.1% | 12.3% | 0.86 (0.73–1.1) | 14% | 1.8% | 55 |

| Harris et al.,133 1999, CT double blind placebo control, 3 years | n=2458 ♀ pom and ≥1 FV | Ris=2.5mg/d | 16% | 11% | 0.36 (0.12–0.60) | 64% | 5% | 20 |

| Ris=5mg/d | ||||||||

| Reginster et al.,134 2000, CT double blind, placebo controlled, 3 years | n=1226 ♀ and OP pm and ≥2 FV | Ris=2.5mg/d | 0.40 (0.17–0.65) | 60% | 10% | 10 | ||

| Ris=5mg/d | ||||||||

| Chesnut et al.,c 2005, CT double blind placebo controlled | n=2946 ♀ and OP pm and 1–4 FV | Ibn=2.5mg/d | 9.6% | 4.7% | 0.49 (0.22–0.76) | 51% | 4.9% | 20 |

| Ibn=20mg/2 d 12, dose/3 months | 0.47 (0.19–0.76) | 53% | 4.7% | 21 | ||||

| Black et al.,148 2007, CT double blind placebo controlled, 3 years | n=7765 ♀ and OP pm (62% FV) | Zol=1 annual infusion (5mg) | 10% | 3.3% | 0.30 (0.24–0.38) | 70% | 7.6% | 13 |

| Lyles et al.,149 2007, CT double blind placebo controlled, 1,9 years* | n=2127 patients with FC | Zol=1 annual infusion (5mg) | 3.8% | 1.7% | 0.54 (0.32–0.92) | 46% | 2.1% | 48 |

| Chesnut et al.,107 2000, CT randomized, 5 years | n=1255 ♀ and OP pm and FV | Calciton=100, 200, 300U/d | 0.67 (0.47–0.97) | 33% | 6.2% | 16 | ||

| Ettinger et al.111, 1999, CT blind placebo controlled, 3 years | n=7705 ♀ and OP pm (30% FV) | Ral=60mg/d | 4.5% | 2.3% | 0.45 (0.29–0.71) | 55% | 2.2% | 45 |

| Ral=120mg/d | 21.2% | 14.7% | 0.70 (0.56–0.86) | 30% | 6.5% | 16 | ||

| Silverman et al.,116 2008, CT blind placebo/active controlled, 3 years | n=7492 ♀ and OP pm (56% FV) | Baz=20mg/d | 4.1% | 2.3% | 0.58 (0.38–0.89) | 42% | 1.8% | 55 |

| Baz=40mg/d | ||||||||

| Cummings et al.,d 2010, CT blind placebo controlled, 5 years | n=8556 ♀ and OP (28% FV) | Las=0.25ng/d | 9.3% | 5.6% | 0.36 (0.12–0.60) | 41% | 3.7% | 27 |

| Las=0.50ng/d | ||||||||

| Neer et al.,179 2001, CT randomized placebo controlled, 21 months* | n=1637 ♀ pm and FV | Trp=20μg/d | 14.3% | 5% | 0.35 (0.22–0.55) | 65% | 9.3% | 11 |

| Trp=40μg/d | ||||||||

| Greenspan et al.,182 2007, EC double blind placebo controlled, 18 months | n=2532 ♀ and OP pm (20% FV) | PTH (1–84)=100μg/d | 3.4% | 1.4% | 0.42 (0.24–0.72) | 59% | 2% | 51 |

| Meunier et al.,e 2004, CT phase III placebo controlled, 3 years | n=1649 ♀ and OP pm and ≥1 FV | rSr=2g/s | 32.8% | 20.9% | 0.41 (0.48–0.73) | 59% | 12% | 8 |

| Cummings et al.,163 2009, EC placebo controlled, 3 years | n=7868 ♀ and OP pm (23% FV) | Den=60mg/6 months | 7.2% | 2.3% | 0.32 (0.26–0.41) | 68% | 4.9% | 20 |

| Hip fracture | ||||||||

| Black et al.,a 1996, EC double blind placebo controlled, 3 years | n=2027 ♀ with ↓ BMD and ≥1 FV | Aln=5mg/d→10mg/d | 0.49 (0.23–0.99) | 47% | 1% | 91 | ||

| McClung et al.,f 2001, CT randomized placebo controlled, 3 years | n=5445 ♀ (70–79 years) OP and 1 FR no hip fx | Ris=2.5mg/d | 0.50 (0.30–0.90) | 50% | 1% | 99 | ||

| Ris=5mg/d | ||||||||

| n=3886 ♀ ≥80 years and ≥1 FR no hip fx or ↓ BMD | 0.80 (0.60–1.20) | NS | NS | NA | ||||

| Black et al.,148 2007, CT double blind placebo controlled, 3 years | n=7765 ♀ and OP pm (62% FV) | Zol=1 annual infusion (5mg) | 0.59 (0.42–0.83) | 41% | 1.1% | 91 | ||

| Lyles et al.,149 2007, CT double blind placebo controlled, 1.9 years* | n=2127 patients with FC | Zol=1 annual infusion (5mg) | NS | NS | NS | NA | ||

| Reginster et al.,196 2005, CT double blind placebo controlled, 5 years** | n=5091 ♀ and OP pm (55% FV) | rSr=2g/d | NS | NS | NS | NA | ||

| Cummings 2009,13 CT randomized placebo controlled, 3 years | n=7858 ♀ and OP pm | Den=60mg/6 months | 0.60 (0.37–0.97) | 40% | 0.5% | 200 | ||

Aln: alendronate; Baz: bazadoxifene; Calciton: calcitonin; BMD: bone mineral density; CT: Clinical trial; FC: fractura de cadera; no hip FR: nkeletal risk factor for hip fracture; FV: vertebral fracture; CI: confidence interval; INT: intervention; mg: milligram; μg: microgram; ng: nanogram; Las: lasofoxifene; NA: not applicable; NNT: number needed to treat; NS: no statistical significance; OP: osteoporosis; PLC: placebo; pm: posmenopausal; Ral: raloxifen; Ris: risedronate; RR: relative risk; RRA: Absolute risk reduction; RRR: relative risk reduction; rSr: strontium ranelate; Trp: teriparatide; Zol: zoledronate.

RR: incidence in exposed/incidence in non-exposed; the probability of an event occurring (i.e. fractures). If <1, the intervention is protective.

RRR: (1-RR)100; if an intervention reduces the risk of an event, the RRR expresses the percentage in which the intervention would contribute to the reduction of the risk of the event relative to that occurring in the control group.

RAR: (incidence in non-exposed−incidence in exposed)×100; refers to the percentage of events that could be avoided by intervention. If 0.40 (i.e. 40%), of every 100 persons treated with the intervention could lead to the avoidance of 40 events.

NNT: 1/RAR; necessary number of patients that should be treated to avoid an event.

In a subgroup of 1.977 women with a very elevated risk of fracture (mean age 80) there was a reduction in risk of 36% (P=.046).

Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, et al. Randomized trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet 1996;348:1535–41.

Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA 1998;280:2077–82.

Chesnut CH, Ettinger MP, Miller PD, Baylink DJ, Emkey R, Harris ST, et al. Ibandronate produces significant, similar antifracture efficacy in North American and European women: new clinical findings from BONE. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:391–401.

Cummings SR, Ensrud K, Delmas PD, LaCroix AZ, Vukicevic S, Reid DM, et al. Lasofoxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:686–96.

Currently, HRT should not be recommended for the treatment of postmenopausal OP, except for women with early menopause, intense climacteric symptoms or in the case of not being able to administer other OP drugs due to adverse effects or ineffectiveness (LE 1c; DR B; DA 95%).

Estrogens may reduce the incidence of vertebral and peripheral fractures, although drugs such as alendronate are superior.103,104 There is evidence that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) increases the risk of breast cancer, heart disease, stroke and venous thromboembolism.105

CalcitoninCalcitonin can be administered as a preventive measure and as a second line treatment of postmenopausal OP, after bisphosphonates, and may be indicated in the treatment of recent symptomatic vertebral fractures (LE 1c; DR B; DA 70%).

Calcitonin prevents loss of BMD in the spine,106 reduces the risk of new vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with a history of vertebral fractures, but not the risk of peripheral fractures.107 It also has an analgesic effect in patients with vertebral fractures.108 Its effectiveness seems to be maintained in the long term.

RaloxifeneRaloxifene is recommended as second line treatment of postmenopausal OP (LE 1a; DR A; DA 90%).

Raloxifene decreases the loss of BMD109 and reduces vertebral fracture risk in women with postmenopausal OP with and without fractures, but does not reduce the risk of non-vertebral fractures.110,111 In addition, it decreases serum cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, although it does not seem to reduce the risk of heart disease. It also decreases the incidence of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer,112 but is associated with increased thromboembolic events.113,114

BazedoxifeneBazedoxifene is an alternative to raloxifene in the treatment of postmenopausal OP (LE 1c; DR B; DA 83%).

Bazedoxifene has demonstrated its protective action in BMD loss and reducing vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with OP and, like raloxifene, has shown efficacy in reducing vertebral fractures, except in high-risk fracture population (post hoc). At a dose of 20mg the most common side effects, cramps and hot flashes, were matched to raloxifene and deep vein thrombosis was observed in 0.4 and 0.2% of patients receiving bazedoxifene and placebo,115,116 respectively.

BisphosphonatesThe panel recommends bisphosphonates (BF) as first-line drugs in the treatment of OP (LE 1a; DR A; DA 100%).

BF are currently the most widely used drugs in the treatment of OP.117 Its anti-fracture effectiveness has been amply demonstrated118–121 and are generally well tolerated. On the other hand, the rate of adherence to treatment in the medium or long term (1 year) is low, between 47% in the monthly presentation and 30% in the weekly presentation. Therefore, measures aimed at improving patient compliance must be implemented.122

We do not have enough evidence to recommend one drug over another, so the choice will be based on other factors such as dosage, characteristics, patient preferences and physician experience with the use of BF.

There is no general agreement on the optimal duration of treatment, although an average period of 5 years is advised, after which its continuation, suspension or discontinuation or replacement by another drug should be evaluated, taking into account the estimated residual risk of fracture at the time.123

Before starting treatment, an adequate calcium and vitamin D supplementation should be ensured as well as basic guidelines to follow: BF should be taken in the morning (standing or seated with a glass of 200ml of water), fasting since the previous day and waiting at least half an hour (1h for monthly dose) before eating solid foods or drinking (except water).

The different BF approved for use in OP will now be discussed. For more information, see Tables 4 and 5.

EtidronateEtidronate increases bone mass and moderately reduces the risk of vertebral fractures in women with OP, with a duration of 4 years,124,125 but does not significantly reduce the risk of hip and non-vertebral fractures. Its continued use can cause osteomalacia.126

AlendronateAlendronate significantly reduces the risk of vertebral and non-vertebral fractures, including the hip. Currently, the most common form of administration is a once weekly dosing of 70mg. Although optimal duration of treatment127 was observed when the drug was discontinued after 5 years of treatment, 5 years later a decrease in lumbar and hip BMD was seen, 3.7 and 2.4% compared with when it was continued for 10 years and remodeling markers increased, with no differences in fracture incidence between groups (except clinical vertebral fractures), so treatment may be maintained for 10 years,128 but this also opens the possibility of a “therapeutic holiday” at 5 years due to the residual effect of the drug on the risk of fracture.

There is a presentation containing alendronate and vitamin D, and generic alendronate sodium with a similar bioequivalence with the brand product. Slight differences were observed in the in vitro decay129 and esophageal transit,130 raising doubts about some generic formulations, which may have lower bioavailability and potency, and greater ability to cause esophageal adverse effects.131 Because generic prescribing is a central objective of health systems, independent studies are needed for the clinician to prescribe generics without reserve.132

RisedronateRisedronate is effective in reducing the risk of vertebral and non-vertebral fractures, including hip and postmenopausal OP in women with and without previous fractures.133–137 The most commonly used dosage is 35mg/week orally138 and there is also a presentation that allows its administration in doses of 75mg monthly given in 2 consecutive days. There is also a generic preparation.

IbandronateIbandronate is effective in preventing vertebral fractures at a dose of 2.5mg/day orally in postmenopausal women with OP with and without prior fractures. Efficacy in non-vertebral fractures is significant only in the subgroup with higher risk. It has no efficacy in hip fracture. The bioequivalent single dose of 150mg may be used monthly.120,139–144 It may also be administered as an intravenous injection of 3mg every 3 or 4 months,145 which has an acceptable safety profile and may be performed as an outpatient procedure,146 as an option for patients with obvious risk of compliance failure.147

ZoledronateThis BF is marketed for intravenous use only. Its standard dose is annually, 5mg, day. It is effective in reducing the incidence of clinical vertebral fractures, morphometric, non-vertebral and hip fractures over 3 years.148 It also reduces overall mortality in patients with hip fractures,149 without a clear explanation in this respect.150 It is an alternative for patients with OP and increased risk of fractures or those who do not tolerate or are contraindicated oral BF.

Adverse Events of BisphosphonatesThe overall safety profile of BF is acceptable (see Table 4). However, a number of adverse events potentially related to BF have been reported, which may be serious.151 Although it is not the purpose of this paper to perform a comprehensive review on the subject, we will discuss some relevant aspects.

The panel, on the basis of available evidence does not believe that there is a need to stop BF for dental procedures in relation to the risk of osteonecrosis (LE 2a; DR B; DA 95%).

There have been reports of osteonecrosis of the jaw (OJ), but its incidence in patients with OP is very low (1/10000 1:100000), and it has been associated with prolonged use of BF.152,153 Among the recommendations issued in this regard, we point out those published by AEMyPS (Table 6), to which we refer the reader.154 These include a proper oral hygiene and review, and if invasive dental procedures are contemplated (tooth extraction or implant), it is better to complete the healing process before initiating BF. On the other hand, there is controversy about the approach to be followed in those patients already taking BF. The panel believes that discontinuation of 3–6 months should be assessed individually, weighing risks and benefits, since the benefit of this practice has not been evaluated scientifically. It has also suggested the use of marker CTX, which above a certain threshold may be associated with increased risk of OJ,155 but there is no consistent evidence to support it.156

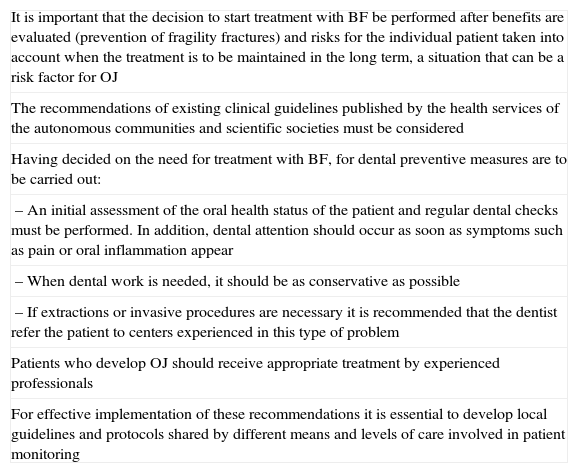

Preventive Measures of Osteonecrosis of the Jaw of the Spanish Agency of Drugs and Health Products.

| It is important that the decision to start treatment with BF be performed after benefits are evaluated (prevention of fragility fractures) and risks for the individual patient taken into account when the treatment is to be maintained in the long term, a situation that can be a risk factor for OJ |

| The recommendations of existing clinical guidelines published by the health services of the autonomous communities and scientific societies must be considered |

| Having decided on the need for treatment with BF, for dental preventive measures are to be carried out: |

| – An initial assessment of the oral health status of the patient and regular dental checks must be performed. In addition, dental attention should occur as soon as symptoms such as pain or oral inflammation appear |

| – When dental work is needed, it should be as conservative as possible |

| – If extractions or invasive procedures are necessary it is recommended that the dentist refer the patient to centers experienced in this type of problem |

| Patients who develop OJ should receive appropriate treatment by experienced professionals |

| For effective implementation of these recommendations it is essential to develop local guidelines and protocols shared by different means and levels of care involved in patient monitoring |

BF: bisphosphonates; OJ: osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Attention should be paid to the occurrence of thigh pain, especially in patients with prolonged treatment with BF, and X-rays used to rule out stress fractures (and try to prevent progress) or identify atypical fractures (LE 2a; DR B; DA 95%).

There have been reports of atypical fractures (subtrochanteric/femur shaft), with a very low incidence (although it could be underestimated). They are usually bilateral, often accompanied of pain of the thighs and/or groin, and are sometimes associated with some comorbidities and/or medications such as HRT, proton pump inhibitors or glucocorticoids.157–159

There is an association between the development of atrial fibrillation and the use of intravenous zoledronate. There are isolated cases of esophageal cancer in patients taking oral BF, though this association has not been confirmed. Musculoskeletal pain, kidney damage and hepatotoxicity associated to BF are exceptional and rarely cause drug withdrawal.160

If significant adverse events occur with the use of BF, the panel recommended suspending BF and evaluating the start of a drug with a different mechanism of action (LE 5; DR D; DA 95%).

If adverse events are significant, such as OJ, occur and although there is no scientific evidence indicating that the withdrawal of the drug improves the outcome of the process, it is prudent to suspend and evaluate the indication of drugs with different mechanisms of action from BF.

DenosumabDenosumab may be recommended as first-line therapy for the treatment of postmenopausal OP with risk of fracture (LE 1b; DR A; DA 95%).

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the formation, activation and survival of osteoclasts. It is therefore, an antiresorptive drug approved for the treatment of postmenopausal OP with a high risk of fracture, at a dose of 60mg/6 months subcutaneously161,162 (Table 4).

Denosumab has been reported to reduce the risk of new vertebral fractures by 68% compared to placebo after 3 years of treatment (RR=0.32, 95%, 0.26–0.41), the risk of hip fractures in 40% (RR=0.60, 95% CI, 0.37–0.97), non-vertebral fractures by 20% (RR=0.80, 95% CI, 0.67–0.95) and multiple fractures (≥2)163 (see Table 5). Its effect is reversible since the inhibition that occurs in bone resorption disappears rapidly as serum levels decline.164,165 It is effective in patients previously treated with alendronate, even without a rest interval,166 and reduced levels of biomarkers of bone turnover, particularly resorption markers, fall faster and more intensely than with alendronate.167,168 It also produces marked increases in BMD at the lumbar spine, total hip and femoral neck, distal radius and total body, from 12 months of treatment onward, with an effect greater than alendronate and far superior to placebo.163,164,167–171

The overall incidence of adverse events was similar to placebo in terms of general infections, cancer, hypocalcemia and cardiovascular events,163,164,167–170 but described a slight increase in urinary tract and skin infections163,172 (see Table 4).

Anabolic DrugsParathyroid Hormone AnalogsPTH analogs can be recommended as first-line drugs for the treatment of OP with a high risk of fracture (LE 1b; DR A; DA 90%).

PTH's osteoforming173,174 effects can prolong the life of osteoblasts, whether administered complete175 or as an amino fraction.176 There are two molecules on the market (see Table 4): teriparatide (Trp) or 1–34 rhPTH used at doses 20mg/day subcutaneously, and the rhPTH 1–84 (PTH 1–84) at doses of 100mg/day subcutaneously. They are, therefore, osteoforming drugs whose effect is primarily anabolic. The main difference is that Trp pharmacokinetics are found elevated within 3h, while the PTH 1–84 lasts up to 9h.177,178

PTH 1–34 reduces the incidence of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures but not hip fractures, both as monotherapy and associated with HRT.179,180,181 PTH 1–84 shows effectiveness in reducing vertebral fractures in women with and without previous fracture.182 Both are superior to alendronate in increasing BMD183–186 (Table 5).

There is a limit of the duration of therapy to 2 years, both for Trp as for PTH 1–84, due to the occurrence of osteosarcomas in Fischer rats treated with Trp179,187 for 2 years, although in humans this association is not proven.188–190

Adverse reactions generally are not serious with either drug. Mainly hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria177–179,182,191,192 occur, so it is advisable to monitor the levels of calcium in blood and urine in patients starting treatment. This monitoring of serum and urinary calcium during treatment is necessary only with PTH 1–84. For more information, see Table 4.

Mixed Action DrugsStrontium RanelateStrontium ranelate (RSR) may be recommended as a first-line drug for the treatment of postmenopausal OP to reduce the risk of vertebral, non-vertebral and hip fractures in a subgroup at high risk (>70 years and femoral neck DXA T ≤3) (LE 1b; DR A; DA 90%).

RSR produces increased bone formation and decreased resorption in moderation, which translates into an actual increase in bone mass and strength.193–195 It is indicated for the treatment of OP in postmenopausal women (Table 4).

BMD increased from 12.7% to 14.4% in the lumbar spine, 5.7% to 8.2% in the femoral neck and 7.1% to 9.8% in the total hip.196,197 However, some of this increase is due to the deposition of strontium in bone, so the increase is 50% of what is referred. This effect is maintained for 5 years.198 RSR reduces vertebral fractures by 41% (effect detected in the first year), not 16% vertebral, non-vertebral fractures by 19% higher and hip fractures by 36% in a high-risk subgroup after 3 years of treatment (Table 5). This benefit remains up to 8 years afterward.199

Although the possibility of an increased tendency for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism exists, it is not clearly demonstrated.200 The data sheet recommends caution in patients at risk for these events. There have also been cases reported of DRESS syndrome201,202 and, although very rare, it is recommended that patients be informed to discontinue treatment if a rash appears and seek medical attention. The rest of the adverse events are generally mild and transient203 (see Table 4).

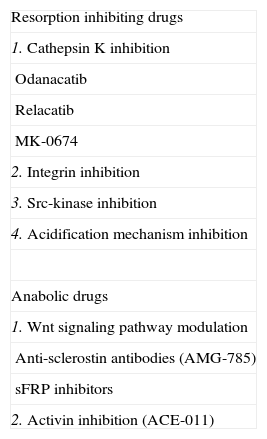

Drugs in DevelopmentTable 7 shows the drugs that can potentially increase the currently available arsenal against OP. Antiresorptive drug development is more advanced than that of anabolic drugs.

Drugs in Development.

| Resorption inhibiting drugs |

| 1. Cathepsin K inhibition |

| Odanacatib |

| Relacatib |

| MK-0674 |

| 2. Integrin inhibition |

| 3. Src-kinase inhibition |

| 4. Acidification mechanism inhibition |

| Anabolic drugs |

| 1. Wnt signaling pathway modulation |

| Anti-sclerostin antibodies (AMG-785) |

| sFRP inhibitors |

| 2. Activin inhibition (ACE-011) |

Some seem to inhibit cathepsin K, whose main function is to degrade bone matrix, rapidly, selectively and reversibly204–206: odanacatib and MK-0674.207

Also in development are drugs capable of inhibiting integrins,208 Src kinase209 or interfere with the acidification process (chloride channel, vacuolar ATP-ase).210

Developing anabolic drugs act on two regulatory elements of osteoblastic activity: the Wnt signaling pathway and activins.211–217

Combination and Sequential TherapyWe recommend antiresorptive therapy is instituted at the end of the 24 months cycle of anabolic drug administration and it is not recommended concomitantly with BF (LE 1b; DR A; DA 100%).

PTH analogs may be administered sequentially with bone resorption inhibitors or mixed-acting drugs.180,181,184,218–222 However, the use of raloxifene or estrogen180,181,220 does not seem to inhibit their action. The fact of having received prior treatment with antiresorptive does not appear to alter the anabolic effect of Trp.223,224

Combined treatment with antiresorptives cannot be recommended across the board, although their use might be justified in highly selected cases (LE 5; DR D; DA 85%).

Multiple associations were tested: etidronate and estrogen,225 alendronate,226 risedronate227 or Trp,180,221 raloxifene plus alendronate,109 Trp228 or PTH (1–84) with raloxifene184,218 and Trp.220 The combined administration of these drugs achieved, in most cases, a greater increase in BMD than monotherapy, but there is no clear evidence that it improves anti-fracture efficacy. Only the concomitant use of estrogen and Tpr has shown a significant reduction of new vertebral fractures.180 However, combinations of these drugs are well-tolerated and no adverse effects could be seen on bone tissue.

What Patients Should Undergo Drug Treatment?Initiate pharmacological treatment (LE 5; DR D; DA 74%):

1. Postmenopausal women:

- –

Low-trauma fracture intensity, regardless of the value of BMD.

- –

OP (BMD below −2.5 SD in the T-score of the spine and/or femur) with or without fractures, assessing risk factors.

- –

The use of FRAX algorithmA may help in decision making when considering the establishment of drug treatment.

Evaluate pharmacologic treatment:

- –

Early menopause (<45 years) by DXA and/or other risk factors.

- –

Osteopenia (BMD between −1 and −2.5 SD on the T-score) Treatment is reserved for very specific cases, as would be intense osteopenias near the OP range in younger women with high risk factors for fracture.

Table 1 shows the most important risk factors12; some may be by themselves an indication for treatment, such as administration of glucocorticoids in doses higher than 5mg/day for over 3 months.

How Long Should Treatment Be Maintained and How Does One Assess its Effectiveness?Treatment of OP, unless contraindicated, should be maintained for years (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

The two PTH analogs can be administered only for 24 months. The rest have maintained their efficacy and safety for varying periods: 10 years for alendronate, risedronate and etidronate up to 7 years ibandronate 3 years,139,148 raloxifene 8 years,229 zoledronate 6 years,230 calcitonin 5 years,107 denosumab 3 years,163 and rSr 8 years.199 We must remember that there have been reports of atypical fractures with prolonged treatment with BF.231

Anti-osteoporotic drugs reduce but do not eliminate the risk of new fractures, so that treatment can be effective even though the patient has new fractures.

It is recommended to assess response to treatment by central DXA every 2–3 years regardless of the type of drug (LE 5; DR D; DA 75%).

At the beginning of treatment it may be desirable to repeat a central DXA at one year and, in situations of high risk for fracture such as transplanted patients, high dose steroids and multiple vertebral fractures, every 6 or 12 months (LE 5; DR D; DA 75%).

Bone turnover markers may be useful to assess the effectiveness of early treatment and to help improve its persistence (LE 2c; DR C; DA 80%).

It is recommended to evaluate the therapeutic response to anti-osteoporotic drugs with central DXA, taking into account the characteristics of each patient.22,23,232–235 Bone turnover markers may be useful to assess its early efficacy.22–24

The appearance of new fractures with a decrease in BMD values over 2%, which corresponds to the minimum significant change after at least one year of treatment, may be seen as an inadequate therapeutic response. If there is only one of those two situations, the response is probably inadequate. By contrast, an appropriate response to treatment will be defined by the absence of these negative circumstances.24

What Is the Most Appropriate Anti-osteoporotic Drug?The selection of a specific drug for a patient with OP should be based on: (a) evidence of efficacy in patients with the same characteristics, (b) absence of contraindications, (c) real possibility of compliance; (d) adverse events, and (e) efficiency of prescription.

Efficiency should be considered as a requirement in its entirety and not just by the price of the drug, given that factors such as costs associated with its administration or affect its anti-fracture effectiveness reflect on treatment costs. The prescription must be viable and take into account other associated treatments and empower the patient to achieve optimal compliance.

The patient must be informed to participate in decisions making regarding the selection of a particular drug (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

Male OsteoporosisIn the male, the densitometic diagnostic approach of OP is the same as in women (LE 5; DR D; DA 95%).

OP is a common male problem, and has a similar or higher morbidity than in women. The prevalence of densitometry OP in Spanish men >20 years of age is estimated between 2.5% and 4.2%,236,237 that of radiographic vertebral fractures is 20% in men <65 years and in 25% >65 years,238 and the incidence of hip fracture is 73–115/100000 inhabitants >50 years.239,240 However, its diagnostic suspicion is usually low, unless there are clear risk factors (steroids, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc.).

In males, it is advisable to perform a basic study of the most common causes of secondary OP through a clinical history and the required laboratory tests (LE 5; DR D; DA 100%).

There are differences in etiopathogenesis241 and in risk factors between men and women. Secondary OP is more common in males.241–244 In Spain, the most common cause is hypogonadism (10%–20%),242 followed by chronic corticosteroid therapy and alcohol abuse, usually associated with liver disease.245,246

In the treatment of male OP the same general measures as in women, and the use of drugs approved for this purpose are recommended (LE 5; DR D; DA 75%).

Currently, drugs that have indications for male OP are risedronate,247 zoledronate248 and Trp,249 with the same dosage and schedule as in female OP.

It is recommended that monitoring, evaluation and duration of treatment be the same as in female OP (LE 5; DR D; DA 95%).

Premenopausal OsteoporosisIn premenopausal women, the diagnostic criteria differ according to DXA. Thus, the value of BMD should be applied using the Z scale and the diagnosis of “low bone mass” is set if Z scale <−2 SD. The presence of fragility fractures, particularly associated with low bone mass, allows the diagnosis of OP (LE 5; DR D; DA 87%).250,251

About 50% of cases are associated processes, and a comprehensive study is recommended to identify the underlying cause (LE 5; DR D; DA 91%).

The most common causes are glucocorticoid treatment or Cushing's disease, pregnancy, osteogenesis imperfecta or estrogen deficiency, anorexia nervosa and/or intestinal malabsorptive diseases. In addition, it is known that idiopathic forms are frequent associated with hypercalciuria and a family history of OP.

The therapeutic approach includes an adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, exercise, avoidance of tobacco and alcohol,252 and treating the underlying cause.

In patients who only show a decrease in BMD with no other risk factors, pharmacologic intervention is usually not required, although it is advisable to monitor these patients (LE 5; DR D; DA 96%).

Drug therapy is considered in specific cases such as in patients with fractures or in those with associated factors, especially treatment with glucocorticoids and hypogonadism. In these cases, BF, estrogen, calcitonin, PTH treatment or Trp may be indicated.

BF in women of childbearing potential should be used with caution, as there is few data on its safety (LE 5; DR D; DA 96%).

Therefore, contraceptive measures should be indicated in patients undergoing such treatment.7,253

Glucocorticoid-induced OsteoporosisGlucocorticoids (GC) are the most common cause of secondary OP, representing up to 25% of all cases of OP.254 It is also estimated that fractures occur in one third of those treated after one year and 50% at some point in their evolution.255

The risk of fracture caused by GC depends on several factors: BMD at the beginning of treatment, daily and accumulated dose, and underlying disease. BMD loss is rapid, especially during the first year, even at low doses, and trabecular bone is most affected.256 There are individual characteristics that make these patients more vulnerable to lower doses of corticosteroids and develop osteoporosis more than others with higher doses.257 Due to the great changes that occur on the bone microarchitecture, fractures produced by GC appear with BMD values that are higher than in other types of OP, so that the threshold for intervention should be located above the T-score of postmenopausal OP.

The prevention and treatment of OP should begin as soon as possible. Preventive measures should be undertaken in patients using doses equivalent to ≥5mg/day of prednisone for more than 3 months. If there is a history of fragility fractures or the patient is over 65, the start of drug treatment is recommended. In those that do not have fractures and are less than 65 years old, a DXA is indicated and if this presents a T<−1.5 SD, drug treatment is indicated.258

Preventive measures: in patients who are to take prolonged GC the following should be considered: (a) use the lowest GC dose possible and as suspend it as quickly as possible, (b) avoidance of the use of tobacco/alcohol, a balanced diet with adequate calcium intake, etc., (c) prevention of muscle loss and falls with a program of proper nutrition and exercise, (d) supplementation with calcium and vitamin D (LE 5; DR D; DA 90%).

Drug therapy: BF (alendronate, risedronate or zoledronate) and Trp have proven effective in the prevention and treatment of OP due to GC.258–267 All treatments should always be supplemented with adequate doses of calcium and vitamin D. In patients at a high risk of fracture, treatment may be started with osteoforming agents (Trp) followed by BF. Treatment with thiazides (25mg/day) should be considered in patients with hypercalciuria.

According to technical data, drugs for corticosteroid associated OP are Trp, risedronate and zoledronate (see Table 4).

DiscussionAs commented in the introduction, the objective of this document is to update on advances in the different clinical aspects of osteoporosis: diagnosis, evaluation, follow up and treatment. This has been a joint effort by members of the panel and the RU of SER and has entailed a large systematic review on different topics of interest and has provided the necessary scientific strength to emit recommendations with a degree of evidence but also of consensus, providing the reader a more objective evaluation of these recommendations.

This paper highlights a number of new contributions in the field and the inclusion of some tables that complement the various recommendations. On the one hand, we have expanded the areas of clinical interest with pre-menopausal osteoporosis, male osteoporosis and osteoporosis secondary to steroids. Furthermore, we have added two new antiresorptive drugs: bazedoxiphen and denosumab. We have also included the results of systematic reviews aimed at answering the following questions: the relationship of biphosphonates to osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical fractures of the femur, the relationship between calcium supplementation and the occurrence of kidney stones, and the degree of evidence of different algorithms to calculate the risk of fracture. And finally, we have joined the tables that summarize the effectiveness of different drugs in reducing fractures and current approved indications (data sheets), dosage, adverse events and interactions with other drugs.

It is also important to emphasize some observations in this document. The first is the fact that the evaluation of the risk for fracture was one of the topics that generated a greater debate among the panel members, because it had been intended that the same criteria as previous documents or the FRAX© algorithm were to be used. The panel's solution was to expose both options so that the reader may have the largest information possible and so that it may help in identifying patients at risk for osteoporosis.

The degree of evidence of the different drugs is based on its “main studies” and in most of them the primary objective was the reduction in vertebral fractures, noting that the efficacy in the reduction of non-vertebral and hip fractures does not represent the same degree of evidence. Only rSr and risedronate have carried out studies in which the primary objective has been non-vertebral and hip fractures, respectively.

As stated in this document and, according to the European Drug Agency, indications for the use of bazedoxiphen and denosumab are for women with high risk of fracture, contrasting with the analysis of their main studies which were based in populations with a majority of patients without previous fracture, making them moderate in risk. It is necessary to take this into account when choosing appropriate treatment.

In conclusion, the recommendations of this document constitute a background for management of OP. They are general norms that must be individualized in a role we, as professionals, must assume.

DisclosuresThe authors have no disclosures to make.

Please, cite this article as: Pérez Edo L, et al. Actualización 2011 del consenso Sociedad Española de Reumatología de osteoporosis. Reumatol Clin. 2011;7(6):357–79.