Hajdu-Cheney syndrome or acro-dento-osteo-dysplasia syndrome is a rare disease characterized by band osteolysis of distal phalanges and facial dysmorphia, among other manifestations. We present the case of a 45-year-old male who consulted for mechanical joint pain of both hands, facial dysmorphism, cranio-facial alterations, and digital telescoping with acroosteolysis.

El Síndrome de Hajdu-Cheney o Síndrome acro-dento-osteo-displasia es una enfermedad rara caracterizada por osteólisis en banda de falanges distales y dismorfia facial, entre otras manifestaciones. Describimos el caso de un varón de 45 añosque consultó por dolor articular de características mecánicas en manos, asociando dismorfia facial, alteraciones craneofaciales y deformidades digitales en telescopaje con acroosteólisis.

Hajdu-Cheney syndrome (HCS) is a rare disease initially described by Hajdu in 1948 and more extensively studied by Cheney in 1965.1 The disease has been linked to mutations in the NOTCH2 gene located on chromosome 1 (1p13-p11).2

The NOTCH signalling pathway is highly relevant and highly conserved in multicellular organisms, participating in multiple processes related to tissue development and differentiation. Its activation requires direct contact between adjacent cells, and so far 4 types of receptors (NOTCH 1-4) and 5 ligands (JAG1, JAG2, DLL1, DLL3 and DLL4) have been discovered. In HCS, gain-of-function mutations occur, resulting in an accumulation of NOTCH2 that causes excessive signalling on osteoclasts, leading to marked bone resorption. An additional mechanism contributing to this alteration is through the increase of TNFα and its promoting action on osteoclast differentiation and activation. Thus, HCS is a disease that combines both processes, inflammation and bone destruction. Unlike in the case of HCS, the loss of function in the NOTCH gene has been related to a series of congenital diseases such as Adams-Olivier syndrome or Alagille syndrome.2,3

In most cases the inheritance is autosomal dominant, although sporadic cases have been described.2 The most characteristic clinical manifestations affect the craniofacial mass and skeleton, although there may be cardiological, neurological or renal manifestations.4 These patients may present to the rheumatologist for mechanical joint pain, acroosteolysis and fragility fractures, given their association with osteoporosis5 There is currently no specific treatment, the usual approach being symptomatic management and management of associated complications.6 In this respect, the indication of antiresorptive drugs such as bisphosphonates or denosumab for the treatment of osteoporosis in these patients is common. Recently, romosozumab has been postulated as an attractive alternative, given that it is the drug which produces the greatest densitometric response.7

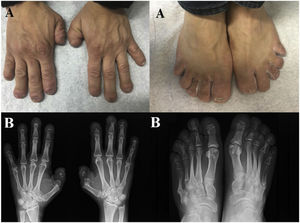

Clinical observationA 45-year-old man, with no personal or family history of interest, consulted for painless deformity of the hands and feet, which in the last 2 years had been accompanied by pain of mechanical characteristics. Anamnesis was negative for inflammatory/autoimmune rheumatic disease. Physical examination revealed complete dental loss, retrognathia, hypertelorism and digital telescoping in the hands and feet. Blood and urine tests, including acute phase reactants and autoimmune markers, were normal. Radiological examination showed band osteolysis in the distal phalanges of the hands and feet, associated with pseudofractures of the 4th and 5th metatarsophalangeal joints (MTP) of the left foot and the 5th MTP of the right foot (Fig. 1).

Given these imaging tests and the absence of other data indicative of more conventional diseases, such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a congenital osteolysis syndrome was suspected. The genetic study detected a mutation at the level of exon 34 of the NOTCH2 gene (variant p.Q2208X), diagnostic of HCS. Extension studies detected mild platybasia and densitometric vertebral osteoporosis (Z-Score: 4DS). The patient is currently receiving analgesic and antiresorptive treatment, without requiring surgical intervention due to platybasia.

DiscussionHCS is a clinical rarity (estimated prevalence < 1/1,000,000 inhabitants) that can nevertheless reach rheumatology consultations and pose a differential diagnosis with more common entities, and it is therefore necessary for the specialist to be aware of it and manage it.1 The disease is due to gain-of-function mutations located in exon 34 of the NOTCH22 gene. Although many variants have been studied, the most common coincide with the one observed in our patient (p.Q2208X)8 This variability leads to significant phenotypic and prognostic differences in patients, although in general they all have in common dental involvement, facial dysmorphia and acroosteolysis.1,5,7,8 The association with osteoporosis is common due to stimulation of signalling pathways involved in bone turnover and osteoclast differentiation.3,6,7,9,10 Clinical manifestations usually begin in childhood or puberty, producing progressive functional deterioration over time.11 Multisystem involvement is common, so it is advisable to perform studies of the extent of the disease, as in our case, where we were able to detect a platybasia that could eventually lead to basilar invagination (the most frequent and serious complication).5

ConclusionHCS is a very rare condition, in which a correct anamnesis, physical examination and the relevant genetic tests are essential. Rheumatologists can collaborate not only in the diagnosis, but also in the management of its complications, such as osteoporosis.

FundingNo funding from other entities was received for the publication of this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.