Chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVRD) is a systemic immune-mediated complication that occurs in approximately half of the patients undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) and, although it is associated with beneficial graft versus tumour effects and lower relapse rates, it remains the leading cause of late morbidity and mortality in these patients. The aim of this systematic review of the literature is to provide a current overview on the diagnostic musculoskeletal manifestations of cGVRD, its clinical evaluation, and therapeutic possibilities.

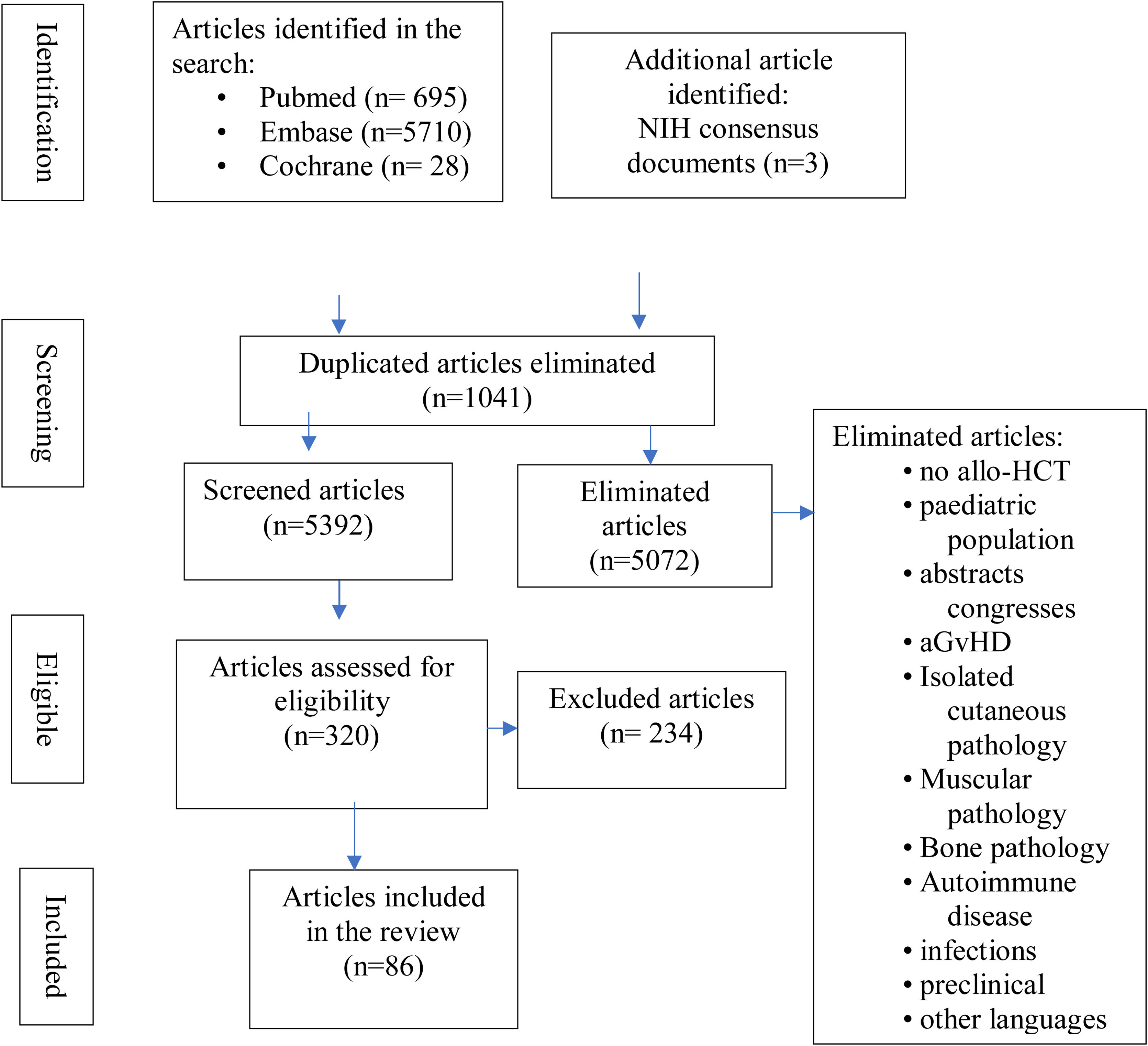

MethodsWe ran a systematic search in PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library. Studies from the last 20 years were included. Priority was given to cross-sectional studies to evaluate diagnostic methods and to clinical trials in the case of articles referring to treatment. The search was limited to humans and articles published in English or Spanish.

ResultsWe identified 6423 studies, of which we selected 86 (37 on clinical and diagnostic evaluation and 49 on treatments). Specific studies on fascial and joint complications are scarce and of low quality, including only isolated clinical cases or case series. Fasciitis is the most relevant musculoskeletal manifestation, and isolated joint involvement is low, sometimes unnoticed and underdiagnosed, if a thorough exploration of joint motion is not performed. Early detection of cGVRD with fascial and/or joint involvement requires careful and repeated evaluation.

ConclusionsThe search for new biomarkers or advanced imaging techniques that allow early diagnosis is necessary. Physiotherapy is essential to improve functionality and prevent disease progression. Controlled studies are needed to establish recommendations on second lines of treatment. Because of its multisystemic nature, cGVRD requires a multidisciplinary approach.

La enfermedad injerto contra receptor crónica (EICRc) es una complicación inmunomediada sistémica que aparece en aproximadamente la mitad de los pacientes sometidos a trasplante alogénico de progenitores hematopoyéticos (alo-HCT) y, aunque se asocia con efectos beneficiosos de injerto versus tumor y tasas de recaída más bajas, sigue siendo la principal causa de morbimortalidad tardía en estos pacientes. El objetivo de esta revisión sistemática de la literatura es proporcionar una visión actual sobre las manifestaciones musculoesqueléticas diagnósticas de EICRc, su evaluación clínica y sus posibilidades terapéuticas.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda sistemática en PubMed, Embase y Cochrane Library. Se incluyeron estudios de los últimos 20 años, y se dio prioridad a los estudios transversales para evaluar métodos diagnósticos y a los ensayos clínicos en el caso de artículos referidos a tratamiento. La búsqueda se limitó a humanos y a artículos publicados en inglés o español.

ResultadosIdentificamos 6423 estudios, de los cuales finalmente seleccionamos 86 (37 sobre clínica y evaluación diagnóstica y 49 sobre tratamientos). Los estudios específicos de complicaciones fasciales y articulares son escasos y de baja calidad, al incluir únicamente casos clínicos aislados o series de casos. La detección temprana de la EICRc con afectación fascial y/o articular requiere de evaluaciones cuidadosas y repetitivas, incluidos exámenes físicos por parte de especialistas con experiencia en trasplantes, comenzando antes del trasplante y continuando a través del seguimiento posterior, para permitir el diagnóstico y la evaluación de la trayectoria de la enfermedad.

ConclusionesEs necesaria la búsqueda de nuevos biomarcadores o de técnicas de imagen avanzada que permitan realizar un diagnóstico precoz. La fisioterapia es esencial para mejorar la funcionalidad y prevenir la progresión de la enfermedad. Se precisan estudios controlados para establecer recomendaciones sobre las segundas líneas de tratamiento. Por su carácter multisistémico, la EICRc requiere un abordaje multidisciplinar.

Allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) is the treatment of choice and the only curative strategy in multiple malignant and non-malignant haematological pathologies.1 It consists of the complete replacement of the patient's haematopoiesis, because it is insufficient or neoplastic, with haematopoietic progenitor cells from a compatible healthy donor, after conditioning the patient with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Its efficacy is based on the beneficial effect of the donor's lymphocytes, responsible for the graft-versus-tumour effect (GvT), in which the donor's T cells act against the host's malignant cells, providing a curative potential in haematopathies in which it is not possible to achieve a cure with the chemotherapy or pharmacological treatment available.2

Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) is one of the major undesirable complications of allo-HCT, correlating with increased mortality, second malignancies and a negative impact on quality of life.3 Current mainstream research aims to minimise the risk of GvHD by maintaining GvT. Chronic GvHD (c-GvHD) has a variable incidence depending on risk factors (30%–70%) and is the most frequent late complication.3,4 The median onset of cGvHD is 6 months after allo-HCT and usually occurs within 3 years after transplantation.4 Clinical manifestations are very diverse; symptoms are characteristic of allo/autoimmune disease with evidence of chronic inflammation and fibrosis of varying intensity. About 50% of patients will have multi-organ involvement.5 The skin is the most frequently affected organ, but other tissues (oral, ocular and genital mucosa, liver, lungs, gastrointestinal tract) as well as joints and fascia are commonly involved. Organ involvement may be simultaneous or successive, with a major impact on the patient's quality of life.6,7 Due to sustained immunosuppression, frequent infections occur, compromising patient survival.

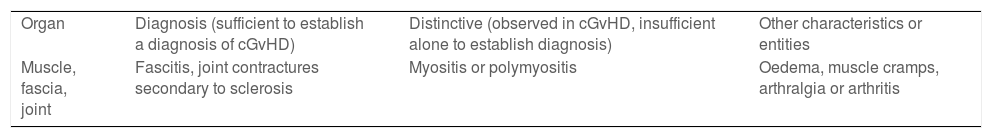

One of the biggest challenges in the management of cGvHD is the establishment of a correct, early diagnosis. Recognising these difficulties, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) promoted the formation of an international consensus group on cGvHD that proposed guidelines for correct clinical and pathological diagnosis, unified response criteria and made recommendations for supportive care,8 with two subsequent updates, the latest in 2020.9–11 This NIH consensus includes fasciitis and/or joint contractures as definitive diagnostic criteria for cGvHD (not requiring additional tests) (Table 1). Reduced joint range of motion is usually secondary to sclerodermiform changes and/or fasciitis, as inflammatory joint involvement has rarely been observed. A correct diagnostic approach to cGvHD requires establishing the diagnosis, scoring the severity of each affected organ and classifying cGvHD as mild, moderate or severe.

Diagnostic and distinguishing criteria of chronic musculoskeletal GvHD.

| Organ | Diagnosis (sufficient to establish a diagnosis of cGvHD) | Distinctive (observed in cGvHD, insufficient alone to establish diagnosis) | Other characteristics or entities |

| Muscle, fascia, joint | Fascitis, joint contractures secondary to sclerosis | Myositis or polymyositis | Oedema, muscle cramps, arthralgia or arthritis |

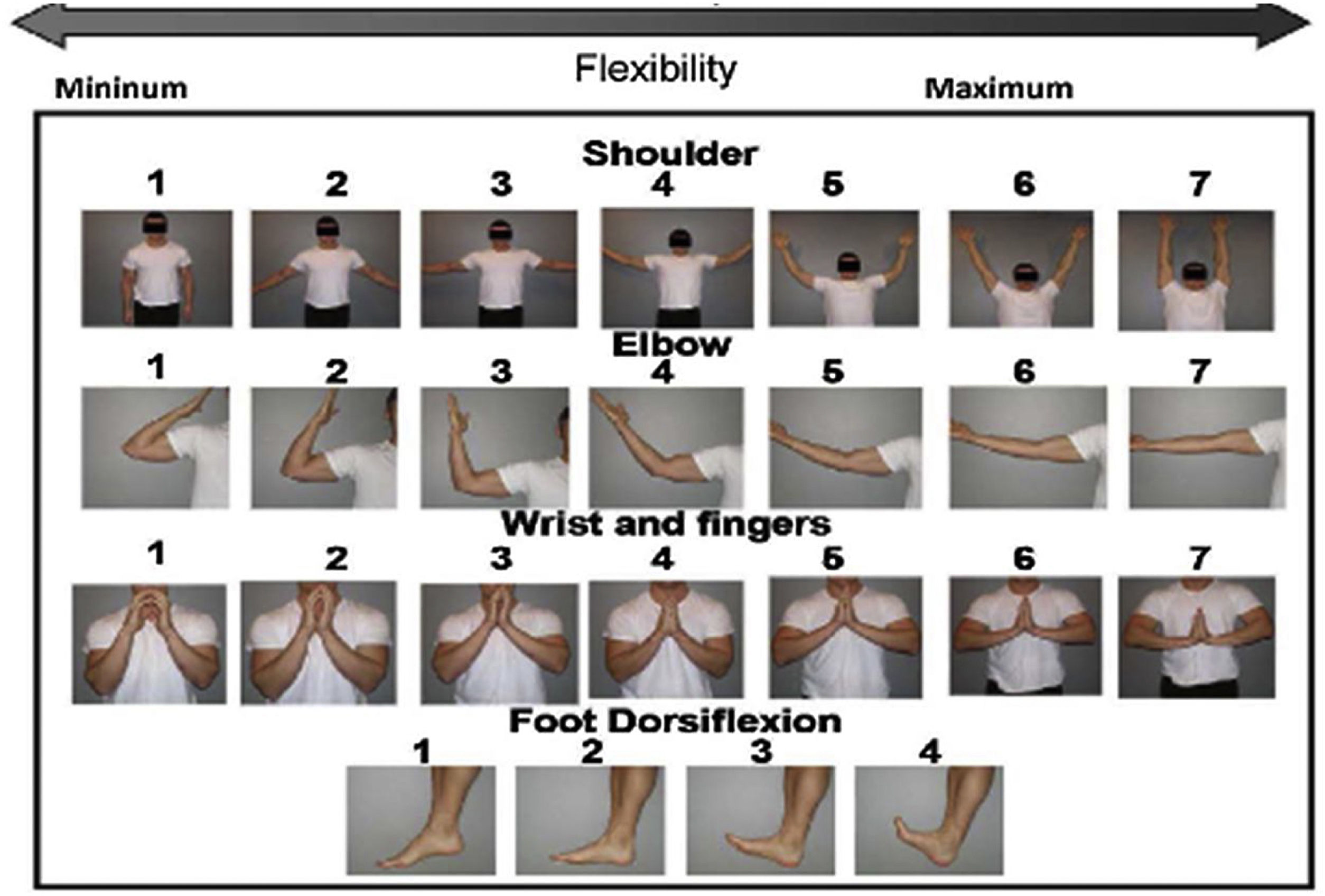

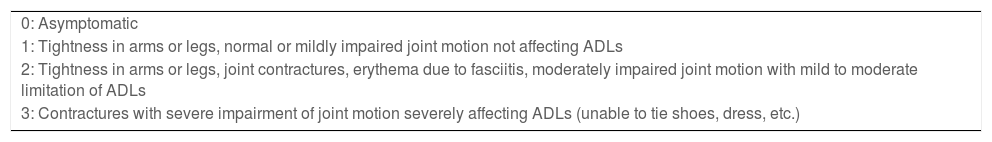

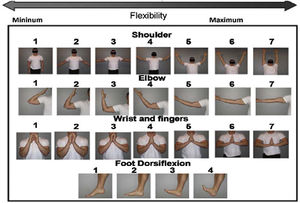

Different scales have been proposed to assess fascia and joint involvement: the NIH Joint and Fascia Score 0–3 is a composite index that assesses joint stiffness, range of motion (ROM) and activities of daily living (ADL) (Table 2). The Hopkins fascial scale uses a 0–3-point scale, but only scores stiffness. The photographic range of motion (P-ROM) scale is a series of images that captures ROM separately for shoulders, elbows, wrists/fingers and ankles; lower scores indicate more limited ROM. The total P-ROM score is the sum of the scores at all 4 joints, with a maximum possible score of 25 (Fig. 1). The use of the P-ROM scale has been a breakthrough in terms of simplicity and objectivity; it is also useful in detecting longitudinal changes by measuring response to treatment. The NIH scale more accurately captures improvement, while the P-ROM scale better captures worsening.12,13

NIH joint/fascial scale.

| 0: Asymptomatic |

| 1: Tightness in arms or legs, normal or mildly impaired joint motion not affecting ADLs |

| 2: Tightness in arms or legs, joint contractures, erythema due to fasciitis, moderately impaired joint motion with mild to moderate limitation of ADLs |

| 3: Contractures with severe impairment of joint motion severely affecting ADLs (unable to tie shoes, dress, etc.) |

ADL: activities of daily life; NIH: North American National Institutes of Health.

The skin is the most frequently affected organ, and is often the initial manifestation of cGvHD. Generalised scleroderma can lead to joint contractures and severe functional limitation, frequently affecting the hands, wrists, shoulders, elbows and ankles.15,16 Fasciitis due to inflammation of the fascia with an eosinophilic component may manifest as stiffness, oedema, arthralgia, reduced motion and occasionally synovitis.17,18

Because of the multisystemic nature of cGvHD, its monitoring and treatment require a multidisciplinary approach.19 Depending on its severity, comorbidities and the risk of relapse of the patient's underlying disease, the first line of treatment in moderate/severe cases is corticosteroids.20 Two out of three patients will not respond adequately and sustainably to this treatment and will require rescue therapy.21,22

ObjectivesTo conduct a systematic review of the literature on musculoskeletal (fascial/articular) involvement as a manifestation of chronic graft-versus-host disease sclerotic phenotype in patients undergoing allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

To describe the clinical features, diagnostic tools and therapeutic possibilities at present, due to the absence of review publications on this topic.

Material and methodsData sources and search strategyA literature search was conducted in PubMed, Embase and Cochrane, using MeSH terms and keywords to select articles with information on chronic graft-versus-host disease and diagnostic musculoskeletal (fascial, joint) involvement, clinical characterisation, methods of diagnostic evaluation and treatments (see search strategy in Appendix Banexo 1 of the supplementary material).

Selection criteriaAs this is a poorly known topic from a rheumatological point of view, a comprehensive search of the existing literature was conducted. Studies from the last 20 years were included. Priority was given to cross-sectional studies to evaluate diagnostic methods and clinical trials for articles on treatment. For clinical manifestations, case series and prospective or retrospective studies were considered. Articles unrelated to the search were excluded (avascular necrosis, bone loss, post-transplant joint infections, Sjögren's syndrome and other systemic autoimmune diseases, osteoporosis, osteonecrosis, osteomyelitis, dermatological involvement only, no allogeneic transplantation), as were exclusively experimental/preclinical studies, in languages other than English or Spanish, those that only included a paediatric population, and those that referred exclusively to acute GvHD (aGvHD). We excluded muscle involvement (myositis) because it is not a diagnostic criterion for cGvHD and because of the existence of a recent systematic review on this condition.23

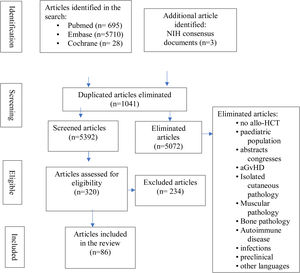

Inclusion criteria were: original studies (clinical trials, systematic reviews, case-controls, prospective or retrospective cohorts, case series, single cases), allo-HCT recipients, and the relationship of musculoskeletal manifestations to cGvHD. Reviewing the references of the most relevant articles, additional publications of interest were identified. Articles were imported into the Zotero reference manager and duplicate articles were removed. All abstracts were read by CHC and MDSG and full articles were obtained for review. Where there were discrepancies they were agreed with the other authors (LLC and JML). Fig. 2 details the flowchart for article selection.

Data extractionWe classified the articles according to the musculoskeletal involvement to which they referred (fasciitis, arthropathy) and according to the subject of the publication (clinical, diagnosis or treatment). We extracted demographic data, post-transplant time of the clinic, differential characteristics, treatment and other results on the different techniques of interest.

ResultsWe identified 6423 studies, of which we reviewed 126 in depth, to finally select 86: 37 on clinical and diagnostic evaluation (28 on fasciitis, of which 23 refer to clinical manifestations clínicas5,14,17–19,24–42 and 5 to diagnosis,13,43–46 and 9 on arthropathy, of which 6 on clinical symptoms6,7,47–51 and 3 on diagnosis13,43–46 and 49 on treatments administered (7 on fasciitis fasciitis,8,12,52–56 9 on arthropathies15,16,57–63 and 33 on therapies administered in sclerodermiform cGvHD with fascial and/or joint involvement64–96) (Fig. 2). Appendix Banexo 2 (additional material) contains all the articles analysed, with the data extracted. Appendix Banexo 3 (additional material) contains a glossary of terms and the colour code associated with each musculoskeletal manifestation for better understanding.

Most of the articles are of low quality, including only isolated clinical cases or case series with a small and uncontrolled sample size (36 articles, approximately 41%). There are also 14 reviews (≈16% reviews or consensuses), 14 (≈16%) retrospective observational studies, 11 (≈12%) prospective and only 7 (8%) phase II trials. We found only 3 systematic reviews: 3 related to treatments (UVA,87 rituximab85 and extracorporeal photopheresis [ECP])79 and a recently published comprehensive narrative review on cGvHD-related eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) by CHC and CLL.24

There is a need to identify early signs, symptoms or other diagnostic determinants of cGvHD which are consistently associated with subsequent progression to highly morbid forms of cGvHD cGvHD.11 Early detection of cGvHD requires careful and repeated assessments, including physical examinations by experienced transplant specialists, starting before transplantation and continuing through subsequent follow-up, to allow formal diagnosis and assessment of the disease trajectory.97 Patient education is important for active participation in the detection of early signs and symptoms.

FasciitisAlthough skin changes are frequent, the detection of fasciitis is not as common and its diagnosis is more difficult, as physical signs and laboratory findings are not always present. Fasciitis is the most relevant musculoskeletal manifestation of cGvHD, with a reported annual incidence of .5%–47%.24,31,41,42,48,54 It is important to distinguish fasciitis from sclerodermiform cGvHD, although the two can coexist in up to 80% of patients.24,48 Oedema is often the first sign of fascial involvement. Fasciitis lesions are usually located in the proximal areas of the extremities and abdomen, sparing the hands and feet.42,52 EF-like in the context of cGvHD looks like pseudocellulitis due to subcutaneous septal and fascial fibrosis, often presenting with skin induration, with typical “orange peel” or rippling appearance, arthromyalgia, peripheral eosinophilia and development of joint contractures in the most severe cases (prayer sign).

A careful patient history and systematic physical examination,5 is very important, as advanced fasciitis is hardly distinguishable from cutaneous sclerotic cGvHD,65 and the gradation of severity should be noted on collection sheets (Appendix Banexo 4, in additional material).45

When examining the patient, progression from easily compressible mobile skin to “non-mobile” and “stone-like” tightness due to diffuse thickening suggests chronic fibrosis that is difficult to reverse.60 Range of motion should be assessed (ideally with P-ROM) in all patients at baseline and at subsequent check-ups, which will allow us to grade severity and monitor response to treatment.5,12,13 Elastography measures33,80 are promising, although no large trials have been conducted to validate them. In this regard, most articles emphasize that the diagnosis of fasciitis should be established by histopathological findings - indistinguishable from those of classic EF - in the deep skin biopsy piel18,25,30,33,41,42 and by the alterations in the fascia seen in magnetic resonance imaging,18,33,34,36 as a non-invasive test,18 that allows us to distinguish between exclusively cutaneous manifestations, fasciitis and myositis, also allowing us to locate the optimal area in which to perform the biopsy.25

On histopathological examination of fasciitis, oedema and fibrosis are limited to the fasciae and subcutaneous septa, with subcutaneous fat trapping and a pericapillary cellular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate.45

The natural history of fasciitis in cGvHD is often progressive, leading to significant impairment of the patient's quality of life and functionality through stiffness, joint contracture and reduced ROM, as well as the development of chronic ulcers and scarring problems, making early diagnosis and therapy with systemic immunosuppression crucial to prevent progression.

CEF, with a 55%–85% response, or PUVA in addition to systemic immunosuppression, can improve fascial involvement and prevent contractures.56,70,75

Physiotherapy is the mainstay of supportive treatment of fasciitis,58,63,98 especially thermal modalities, stretching, joint mobilisation and lymphatic drainage, and should be initiated as early as possible in order to prevent or resolve joint contractures. Strengthening exercises are controversial, as is surgical therapy of affected joints.16 In addition, caution should be exercised with physiotherapy or lymphatic drainage in the acute oedematous stage of fasciitis, as inflammatory processes may be increased by mechanical irritation.

Response to treatment of fasciitis in GvHD is difficult to assess and has often been based on variable and subjective but practical criteria (“complete response”, “partial response”, “no change”, “progression”). Scales of cutaneous or fascial involvement have been prospectively validated.35

ArthropathyFascia/joint involvement is common in patients with cGvHD, but the incidence of isolated joint involvement is low,49 sometimes unnoticed and under-diagnosed in early stages without a thorough examination of joint motion. In advanced stages, they cause sometimes irreversible joint contractures, causing great disability and loss of quality of life.12 The most frequently affected joints are the ankles (93%), followed by the shoulders (19%), wrists and fingers (16%) and elbows (9%). There is a high correlation of fascial/articular sclerosis with skin involvement. High levels of C348 have been reported.

Compared to patients with sclerotic skin changes, patients with joint involvement appear to have less functional disability, start earlier after diagnosis of cGvHD and have lower levels of inflammatory markers.49 Further studies are needed to determine whether joint involvement in the absence of skin changes represents deep tissue involvement below the clinical detection limit or a separate clinical process.

Ultrasound99 and bone scintigraphy100 have been used to diagnose joint involvement, in addition to MRI and CT.

Synovitis related to cGvHD has also been found in the literature, with the presence of donor cells in the synovial infiltration.98

Physiotherapy and rehabilitation are essential - it is important that they are started early: massage, heat, ultrasound, paraffin, stretching, hydromassage, strengthening and ADL training.63

Pharmacological treatmentIn mild cGvHD, topical treatment or systemic corticosteroids are used as monotherapy. If fasciitis is present, NSAIDs should be added. In moderate cGvHD, treatment is with a systemic IS (usually prednisone with or without calcineurin inhibitors) and topical treatment. For severe cGvHD, treatment would be the same as for moderate cGvHD, with the addition of other IS.21

1st line treatment:

- -

Prednisone 1 mg/kg/day for 2–3 weeks, then every other day for 2 weeks and then taper to 1 mg/kg every 2 days for a period of 6–8 weeks if symptoms are stable or improve; maintain this dose for 2–3 months or continue directly to taper by 10%–20% per month.20

- -

Depending on severity, it will be associated with calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine A and tacrolimus).

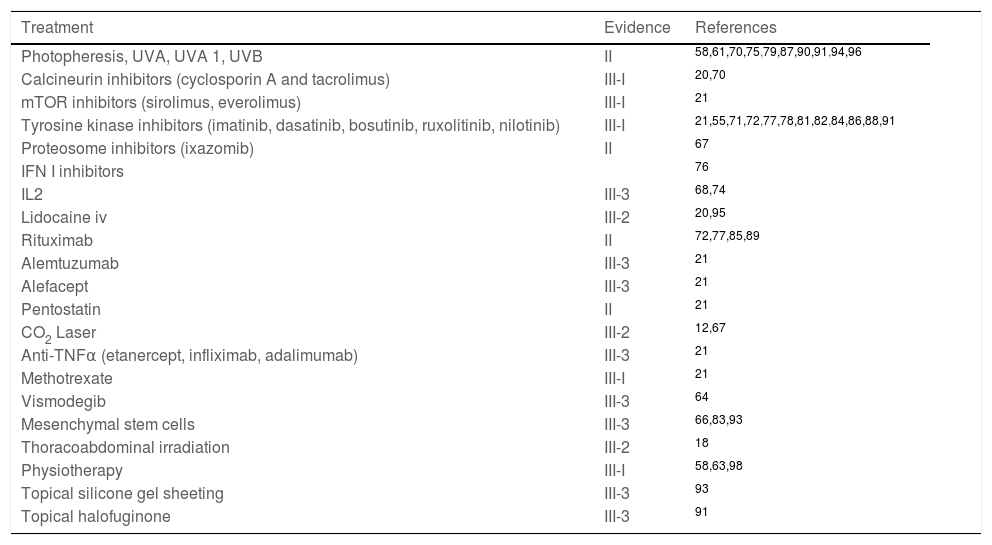

2nd line treatment: There are no established protocols or standard treatment, second-line or salvage treatments are prescribed from the numerous options available and are individually tailored (Table 3).

Salvage treatment options in chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGVHD) with fascial/articular involvement.

| Treatment | Evidence | References |

|---|---|---|

| Photopheresis, UVA, UVA 1, UVB | II | 58,61,70,75,79,87,90,91,94,96 |

| Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporin A and tacrolimus) | III-I | 20,70 |

| mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus, everolimus) | III-I | 21 |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (imatinib, dasatinib, bosutinib, ruxolitinib, nilotinib) | III-I | 21,55,71,72,77,78,81,82,84,86,88,91 |

| Proteosome inhibitors (ixazomib) | II | 67 |

| IFN I inhibitors | 76 | |

| IL2 | III-3 | 68,74 |

| Lidocaine iv | III-2 | 20,95 |

| Rituximab | II | 72,77,85,89 |

| Alemtuzumab | III-3 | 21 |

| Alefacept | III-3 | 21 |

| Pentostatin | II | 21 |

| CO2 Laser | III-2 | 12,67 |

| Anti-TNFα (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab) | III-3 | 21 |

| Methotrexate | III-I | 21 |

| Vismodegib | III-3 | 64 |

| Mesenchymal stem cells | III-3 | 66,83,93 |

| Thoracoabdominal irradiation | III-2 | 18 |

| Physiotherapy | III-I | 58,63,98 |

| Topical silicone gel sheeting | III-3 | 93 |

| Topical halofuginone | III-3 | 91 |

Strength of evidence level:

• II: >1 well-designed clinical trial without randomisation, cohort or case-control, analytical (preferably > 1 centre) or multiple time series studies, or dramatic results from uncontrolled experiments.

• III: opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies or expert committee reports:

◦ III-1: several reports of retrospective evaluations or small uncontrolled clinical trials.

◦ III-2: a report of a small uncontrolled clinical trial or retrospective evaluations.

◦ III-3: case reports.

There is a need to identify biomarkers to predict treatment response.20 CD5+ B cells have been described as a biomarker of response to treatment with rituximab and nilotinib.72

We must also highlight the importance of supportive therapy for long-term patient care, as more and more patients are receiving HCT and hosts are surviving longer,8 and the value of multidisciplinary consultations for comprehensive patient care.24

DiscussionSpecific studies and reviews on musculoskeletal manifestations in cGvHD are limited and of low quality, as we have reflected in the results.

We have found that there is a need for systematic, objective, reliable and simple assessment of joint and fascial manifestations, as early diagnosis and treatment are decisive in the patient's evolution.52

It is noteworthy that the NIH Consensus Fascia/Joint score does not distinguish contributions to severity of cGvHD from isolated joint involvement compared to joint restriction associated with skin sclerosis.6–8

It is true that fascia/joint involvement is common in cGvHD and the incidence of isolated joint contracture in the absence of skin sclerosis is low,49 but it is also likely to be under-diagnosed if a full range-of-motion examination is not routinely performed; hence the importance of recording P-ROM at regular patient reviews.12,42

Further studies are needed to determine whether joint involvement in the absence of sclerotic skin changes represents deep tissue involvement below the limit of clinical detection or whether it is a separate clinical process. Future refinements of the NIH criteria may need to recognise joint restrictions that occur in the absence of sclerotic skin involvement.49

The clinical, genetic and biological factors specifically associated with musculoskeletal and joint involvement in patients with cGvHD are unknown.31

In these patients, it is necessary to perform an analytical evaluation for peripheral eosinophilia as an early serological marker of cGvHD, in particular fasciitis, as well as the determination of muscle enzymes.25,29–31 The search for serum biomarkers in this fibrosing entity, such as specific autoantibodies (anti-sclerosis) has so far been unsuccessful. In a series of patients with eosinophilic-like fasciitis related to cGvHD, positive antinuclear antibodies were detected in 25% of patients, with the nucleolar pattern being the most frequent.24

Patients with clinical manifestations suggestive of EF-like cGvHD should undergo deep biopsy (skin, muscle and fascia) and in some cases MRI to assess the extent of involvement and monitor response to treatment.25,30 According to the NIH Consensus, fasciitis is a “diagnostic” entity that does not require confirmation with additional tests, but in the event of suggestive symptoms such as arthralgias, muscle cramps, joint stiffness or tendon rubbing, imaging tests (MRI, high-frequency US) 44,80 and even diagnostic biopsy should be considered in certain isolated or doubtful cases.

Assessment of active joint motion as an objective measure with P-ROM is a very good option in routine practice, together with the NIH joint/fascia scale.12 The NIH joint/fascia score and the P-ROM total score should be used to assess therapeutic response in joint/fascia c-GvHD. A change from 0 to 1 in the NIH joint/fascia score should not be considered as a worsening.

In terms of treatment, high-dose corticosteroids are still used as first line, with their recognised adverse effects (immunosuppression, osteopenia, avascular necrosis, fractures, muscle and skin atrophy, oedema, delayed healing…) and in the case of cortico-refractoriness or intolerance to the first line, there is no established standard treatment, so the decision is based on the circumstances of each patient, analysed on an individual basis. Physiotherapy and other physical therapies have proven to be effective in improving functionality and preventing disease progression, and should be started as early as possible.

ConclusionsMusculoskeletal involvement related to c-GvHD is common and can cause significant functional impairment, with great impact on quality of life. Specific studies of fascial and joint complications are scarce and of low quality. One of the major challenges in the management of c-GvHD is the establishment of a correct, early diagnosis, to improve the likelihood of response to treatment and the prevention of irreversible sequelae. New biomarkers are needed to allow more targeted treatment in patients after first-line treatment failure. Physiotherapy is essential to improve functionality and prevent disease progression and should be started early. Because of the multisystemic nature of c-GvHD, its monitoring and treatment require a multidisciplinary approach.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.