To design a care protocol in Chronic Inflammatory Arthritis during the pre-conceptional period, pregnancy, postpartum and lactation. This protocol aims to be practical and applicable in consultations where patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatological diseases are treated, thus helping to better control these patients. Likewise, recommendations are offered on when patients could be consulted/referred to a specialized center by the physician.

MethodsA multidisciplinary panel of expert physicians from different specialties identified the key points, analyzed the scientific evidence, and met to develop the care protocol.

ResultsThe recommendations prepared have been divided into three blocks: rheumatology, gynecology and pediatrics. The first block has been divided into pre-pregnancy, pregnancy and postpartum visits.

ConclusionsThis protocol tries to homogenize the follow-up of the patients from the moment of the gestational desire until the year of life of the infants. It is important to perform tests in patients of childbearing age and use drugs compatible with pregnancy. If appropriate, the patient should be referred to specialized units. Multidisciplinarity (rheumatology, gynecology and pediatrics) is essential to improve the control and monitoring of these patients and their offspring.

Diseñar un protocolo asistencial en las Artritis Inflamatorias Crónicas durante el período preconcepcional, el embarazo, el postparto y la lactancia. Este protocolo tiene como objetivo ser práctico y aplicable en las consultas donde se atienden a pacientes con enfermedades inflamatorias reumatológicas crónicas, ayudando así a un mejor control de estas pacientes. Asimismo, se ofrecen recomendaciones sobre en qué momento se podría consultar/remitir a las pacientes a un centro especializado por parte del facultativo.

MétodosUn panel multidisciplinar de médicos expertos de diferentes especialidades identificó los puntos claves, analizó la evidencia científica y se reunió para elaborar el protocolo asistencial.

ResultadosLas recomendaciones elaboradas se han dividido en tres bloques: reumatología, ginecología y pediatría. El primer bloque se ha dividido en visita pregestacional, gestación y postparto.

ConclusionesEste protocolo intenta homogeneizar el seguimiento de las pacientes desde el momento del deseo gestacional hasta el año de vida de los lactantes. Es importante realizar análisis en las pacientes en edad fértil y usar fármacos compatibles con la gestación. Si procede, se debe derivar a la paciente a unidades especializadas. La multidisciplinariedad (reumatología, ginecología y pediatría) es fundamental para mejorar en el control y seguimiento de estas pacientes y sus recién nacidos.

Rheumatic diseases frequently affect young patients and those of reproductive age.1 Nowadays, thanks to the introduction of biologic therapies, most patients have long periods of low activity or remission, which means that more can consider becoming pregnant.2 The interaction between rheumatic disease and pregnancy is different for each disease, ranging from improvement to reactivation. It is also important to note that each disease can have different types of complications during this period, for example, one study on psoriatic arthritis showed that the majority (58%) of patients improved during pregnancy and 50% reported worsening during the first year postpartum.3 In another study among 136 pregnant patients, 29% with rheumatoid arthritis and 25% with axial spondyloarthritis had disease flares during pregnancy.4

In general, pregnant women with active disease are at increased risk of complications such as pre-eclampsia, miscarriage, premature delivery, small for gestational age,5 which could have major consequences for the overall health of the child.

During pregnancy, important changes occur at the level of the endocrine and immune systems6 and immune responses at the receptive maternal-foetal interface are not simply suppressed, but are instead highly dynamic.7 Tolerance to foetal antigens is generated during this period, keeping maternal defence mechanisms active (e.g., they will exhibit normal responses to active or passive immunisation).8

Different immunomodulators can be prescribed during pregnancy without teratogenic effects. Some drugs have placental transfer capacity, reaching their maximum transfer in the third trimester of pregnancy. This could cause some degree of secondary immunodeficiency in the neonate and infant, which must be known for it to be appropriately managed.9

There is now a rheumatology subspecialty dedicated to the study of fertility, pregnancy, and pharmacological treatments during pregnancy and breastfeeding.10

ObjectiveThe aim of this document is to generate a care protocol for chronic inflammatory arthritis during the preconceptional period, pregnancy, postpartum, and breastfeeding. This protocol is intended to be practical and applicable to different types of hospital centres, and to help better manage these patients. Recommendations are provided on when to consult/refer patients to a specialist centre. This protocol focuses on chronic inflammatory arthritis in women.

MethodsThis is an expert opinion provided by the multidisciplinary working group (gynaecology, rheumatology, paediatrics, and paediatric rheumatology) of a regional rheumatology society. Regular meetings were held to identify the key points, analyse the scientific evidence, and draw up the consensus document. We conducted a specific non-systematic literature review with an informed selection of current, high-quality review and original articles on arthritis, gestation, and drugs used, available since 2009 in the PubMed database. Each specialty reviewed its part in more depth. The protocol points were then discussed until the consensus recommendation was finalised. The protocol was then shared with all members of the working group for further evaluation, amendment, and approval.

ResultsOrganisation in Rheumatology. Women with pregnancy desireThe preconception visit is essential for the follow-up of these patients.

During this visit, we should undertake a patient global assessment. We will first evaluate the inflammatory component present during the course of the disease and currently present, and verify that the patient has been in clinical remission or has had low disease activity for at least 6 months prior to a planned pregnancy.

Another important point in this period is to assess absolute contraindications10: severe organ damage, pulmonary hypertension (systolic PAP > 50 mmHg or symptomatic), restrictive lung disease (FVC < 1 l), heart failure, chronic renal failure (cr > 2.8 mg/dl), or severe complications in previous pregnancies: severe pre-eclampsia, haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count (HELLP) despite treatment with acetylsalicylic acid or heparin.

Relative contraindications will also be assessed, for example, having disease with significant inflammatory activity at that time or following treatment with drugs that are not compatible with pregnancy. In these cases, pregnancy may be reassessed once this situation has changed.

It is recommended during this visit, that a complete haemogram and biochemistry, acute phase reactants and autoantibodies be ordered relevant to the patient's disease (antinuclear antibodies, anti-ENA antibodies, especially anti-Ro antibody, anti-La antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, and anti-DNA antibodies). The American Society of Rheumatology guidelines advise testing for antiphospholipid antibodies (anti-cardiolipin IgG/IgM antibody; anti-β2 glycoprotein IgG/IgM antibody) and lupus anticoagulant in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus or lupus-like diseases and in patients with suggestive history or findings on examination. In all other patients with a lower likelihood of a positive result, a joint decision should be made with the patient. If these markers have been requested in the last 6–12 months, it is not necessary to repeat them.

In addition, a visit by the obstetrics/gynaecology team or by the midwife is always advisable.

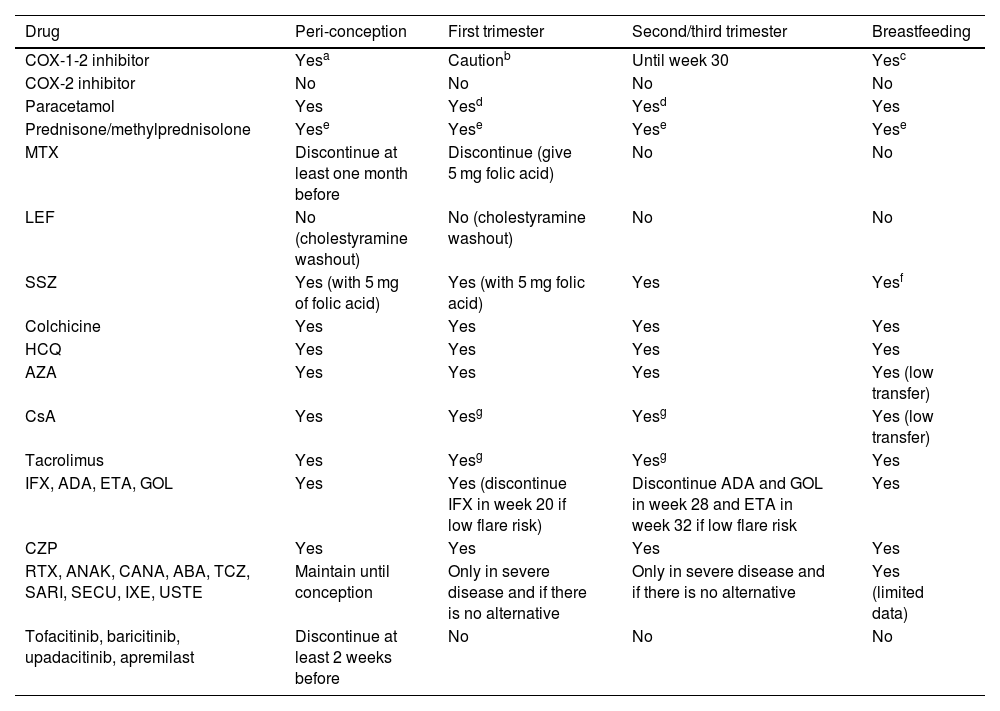

After this evaluation, the compatibility of pharmacological treatments with a potential pregnancy will be assessed. Clinical stability maintained over time with the new treatment should be re-evaluated if modifications have been necessary. Table 111–16 describes the different pharmacological treatments during the pre-pregnancy period, the different trimesters of pregnancy and lactation.

Compatibility of drug treatments during preconception, pregnancy, and lactation.

| Drug | Peri-conception | First trimester | Second/third trimester | Breastfeeding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COX-1-2 inhibitor | Yesa | Cautionb | Until week 30 | Yesc |

| COX-2 inhibitor | No | No | No | No |

| Paracetamol | Yes | Yesd | Yesd | Yes |

| Prednisone/methylprednisolone | Yese | Yese | Yese | Yese |

| MTX | Discontinue at least one month before | Discontinue (give 5 mg folic acid) | No | No |

| LEF | No (cholestyramine washout) | No (cholestyramine washout) | No | No |

| SSZ | Yes (with 5 mg of folic acid) | Yes (with 5 mg folic acid) | Yes | Yesf |

| Colchicine | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| HCQ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AZA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (low transfer) |

| CsA | Yes | Yesg | Yesg | Yes (low transfer) |

| Tacrolimus | Yes | Yesg | Yesg | Yes |

| IFX, ADA, ETA, GOL | Yes | Yes (discontinue IFX in week 20 if low flare risk) | Discontinue ADA and GOL in week 28 and ETA in week 32 if low flare risk | Yes |

| CZP | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| RTX, ANAK, CANA, ABA, TCZ, SARI, SECU, IXE, USTE | Maintain until conception | Only in severe disease and if there is no alternative | Only in severe disease and if there is no alternative | Yes (limited data) |

| Tofacitinib, baricitinib, upadacitinib, apremilast | Discontinue at least 2 weeks before | No | No | No |

ABA: abatacept; ADA: adalimumab; ANAK: anakinra; AZA: azathioprine; CANA: canakinumab; CSA: cyclosporine; CZP: certolizumab; ETA: ettanercept; GOL: golimumab; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; IFX: infliximab; IXE: ixekizumab; LEF: leflunomide; RTX: rituximab; SARI: sarilumab; SECU: secukinumab; SSZ: salazopyrin; TCZ: tocilizumab; UST: ustekinumab.

Source: this table is adapted from information published in 2020 ACR 2020 (12), BSR, and EULAR (13–16).

Intermittent use recommended due to low risk of association with asthma in infancy, and especially in weeks 8–14, because a low risk of cryptorchidism has been reported.

Add steroid-sparing drugs to achieve doses below 20 mg/day. If dose above 20 mg day, consider delaying breastfeeding for 2−4 h.

Finally, it is advisable to consider reviewing the patient's vaccination status. We recommend considering the option of consulting/referring to a specialist consultation on pregnancy and rheumatic diseases for assessment or follow-up at the discretion of the lead rheumatologist. Before prescribing treatment during the preconception period, pregnancy, or breastfeeding, it is recommended that the specific recommendation for each treatment be reviewed in accordance with current guidelines.

Organisation in Rheumatology. The pregnant womanChronic inflammatory arthritisIt is important that the patient can contact her rheumatologist as soon as possible after a positive pregnancy test. In patients who are in remission with the minimum dose of treatment or those who do not require treatment, the patient can be followed up with visits approximately every 2–3 months. In patients who require biologic therapy to control the inflammatory activity of their rheumatic disease, patient visits can be every 2 months. In both cases, there should always be the possibility of monthly visits if required by disease activity and spontaneous visits in case of complication. During the visits, the patient's inflammatory activity will be evaluated, the pharmacological treatments she is following and whether she has any complications of her rheumatological disease. The timing of discontinuing drug treatments prior to delivery will also be planned, if necessary. It is important that patients who require biologic treatment are informed from the first months of pregnancy about possible changes in the vaccination schedule of the newborn baby depending on the treatment received by the mother.

In relation to analytical controls in these patients, it is recommended that control laboratory tests should coincide with the scheduled pregnancy laboratory tests. Likewise, the possibility of additional tests in the event of complications should always be considered. We recommend, if possible, referring patients who do not require treatment or who are in remission with the minimum dose of treatment to the high-risk obstetric clinic for obstetric follow-up. In the case of patients requiring biologic treatment, follow-up during pregnancy should be supervised by the high-risk obstetric unit.

It is recommended to consider consulting/referring to a specialist consultation on pregnancy and rheumatic diseases for assessment or follow-up at the discretion of the lead rheumatologist.

Organisation in Rheumatology. The woman in the postpartum periodThe postpartum period is also an important period to cover and monitor closely, as many rheumatic diseases frequently reactivate during this period. If possible, it is recommended to visit the patient on the obstetric ward before discharge to assess the inflammatory component and to plan restarting her rheumatic treatments.

If the mother has undergone treatment during pregnancy requiring changes to the newborn's vaccination schedule, it is recommended that the paediatric team on the ward be contacted and informed. In cases in which the patient cannot be assessed on the ward, it is advisable to draw up a pre-delivery report specifying when to restart the mother's treatment and the changes to the newborn's vaccination schedule.

If the mother wishes to breastfeed or mix breastfeeding, compatible treatments during pregnancy will be assessed.

We recommend that the first visit to the rheumatology outpatient clinic be made one month after delivery, with the possibility of a previous spontaneous visit if there is a rheumatological complication. It is recommended that visits during the following 6 months be every 2–3 months, with the possibility of monthly visits if required by the disease activity, and spontaneous visits in the event of a complication.

It is recommended to consider consulting/referring to a specialist consultation on pregnancy and rheumatic diseases for assessment or follow-up at the discretion of the lead rheumatologist.

Special situations in which referral to a pregnancy and rheumatic diseases consultation may be consideredThe literature lists the different complications that can occur with CIA such as intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, or premature delivery.17 These complications may be related to the disease activity during gestation or treatments during this period. Therefore, it is recommended to consider the option of referring patients with high inflammatory activity or whose rheumatological disease starts during pregnancy.

Other situations where this option could be considered include patients with CIA refractory to the most common treatments compatible with pregnancy and pregnancy desire, or patients with a delay of more than one year in becoming pregnant in the context of sustained inflammatory activity.

Patients with positive anti-Ro antibodiesIn most cases Anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB antibodies are associated with primary Sjögren's syndrome (SS), but may also be present in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and those with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), as well as healthy individuals.18

Anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B are clinically very relevant during pregnancy because of their association with congenital atrioventricular block (CAVB) and neonatal lupus (NL), a passively acquired autoimmune disease.19

It is now thought that the use of hydroxychloroquine during pregnancy may prevent the occurrence of atrioventricular block in neonatal lupus.20

Patients who test positive for this antibody should be referred to a high-risk obstetric unit for follow-up of the pregnancy and then followed up by neonatology/paediatric rheumatology/paediatric cardiology for the first year of the baby's life.21

It is recommended that a foetal echocardiogram be performed every 2 weeks from the 16th to the 28th week of pregnancy and then monitored in the neonatology unit.

Likewise, before delivery, the neonatology service should be informed of the expected date of delivery to initiate the protocol for babies born to anti-Ro positive mothers from birth.

Organisation of high-risk obstetric visitsPatients with high-risk obstetric pregnancies due to the disease itself and associated treatments will be followed up. In addition, the standardised care required for this type of pregnancy will be provided.

Preferably, patients should receive a pre-conception assessment. During this assessment, medication should be adjusted where necessary, and the pregestational thrombotic risk should be assessed, making the appropriate pharmacological recommendations according to the estimated risk. This risk should be reassessed in the event of any clinical change in any admission, particularly intrapartum or in the immediate postpartum period.

Preconceptional folic acid administration and discussion of breastfeeding recommendations (depending on pharmacotherapy) are also recommended.

Number and frequency of visitsA monthly visit will be made from the beginning of pregnancy until the 32nd week of gestation.

Fortnightly visits will be made from 32 weeks to 36 weeks, and thereafter weekly visits until delivery.

Assessment of the risk of chromosomal abnormalitiesTriple screening for chromosomal abnormalities will be undertaken in the first trimester.

Assessment of the risk for pre-eclampsiaThe risk for pre-eclampsia will be assessed during the first trimester. If required, at-risk cases will receive prophylaxis with acetylsalicylic acid.

Laboratory test and ultrasound monitoringBy protocol, standard laboratory tests will be performed in the first, second, and third trimesters.

Pregnancy monitoring will include the first-trimester ultrasound to assess aneuploidy. The risk of pre-eclampsia will be established during this first ultrasound scan, combined with the analytical data obtained in the first trimester laboratory tests. The second-trimester ultrasound will be performed to assess foetal morphology and the third-trimester ultrasound to assess foetal growth and wellbeing. Foetal growth will be monitored in patients with risk factors.

Influenza vaccine will be administered according to the vaccination schedule, and pertussis vaccine between 26–36 weeks.

DeliveryIn most of the pregnant women, delivery will be decided as per obstetric indication. The gynaecological consultation should consider possible indications for caesarean section that differ from the general population, such as the impossibility of abduction and/or external rotation of the hips due to the sequelae of the disease or hip prosthesis.

Organisation of follow-up by paediatricsThe child of a patient with rheumatic disease should now be considered healthy, and therefore will not require specific follow-up or complementary examinations in this regard. Paediatric follow-up will be as standard for all healthy babies, considering a number of points as detailed below:

- 1

Different rheumatic diseases can affect pregnancy and the normal development of the foetus. Different situations have been described, such as: intrauterine growth restriction, miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, prematurity… in these cases, a protocolised follow-up by neonatology and later by paediatrics will be necessary.22,23

- 2

It will be especially important to know the treatment received by the mother during pregnancy and postpartum to control her disease. Thus, the different risks must be known, especially the teratogenesis of some of the drugs used in the control of different rheumatic diseases, or the lymphopenia and neutropenia associated with drugs such as azathioprine in babies of mothers who have required it during pregnancy.24,25 The compatibility of these drugs with breastfeeding must be known in addition to their effects on pregnancy (Table 1).

Although different biological treatments can currently be used safely during pregnancy with respect to foetal development, we must bear in mind that TNF-alpha is involved in foetal immune development throughout pregnancy and in the protection (of both mother and baby) against intracellular germs such as mycobacteria and leishmania. This transplacental passage occurs primarily from 32 weeks of gestation onwards.26 Therefore, anti-TNF-alpha treatments received by the mother that cross the placenta, mainly during the third trimester of gestation, could affect this process.27 The same applies to any other IgG biologic, whose transplacental passage will be greater from week 32 onwards. In the third trimester, therefore, the use of biologics with transplacental passage should be assessed based on their risk/benefit to maternal health and that of the newborn, with pregnancy planning based on multidisciplinary care models. In general, and except for anti-TNF-alpha, the evidence on the impact on the use of biologics and small molecules during pregnancy is very low.

The recent 2022 British BSR guideline makes a recommendation on when it would be advisable to discontinue the different anti-TNF-alpha drugs so as not to affect the baby's vaccination schedule. It would not be necessary to discontinue certolizumab in the third trimester of pregnancy due to its minimal transplacental passage. Etanercept should be stopped at 32 weeks, adalimumab and golimumab at 28 weeks, and infliximab at 20 weeks.

If the risk of reactivation in the mother on discontinuation of the drug is moderate/high, the recommendation would be to maintain the drug in the third trimester. In this case, attenuated vaccines would not be recommended until 7–12 months of age (at 12 months of age the drug is considered undetectable). Rotavirus, BCG, and attenuated intranasal influenza vaccines should be considered in this age group.28 The 2022 American guideline28 states that the rotavirus vaccine is the exception only in those exposed to anti-TNF-alpha, which can be administered in the first 6 months of life of the newborn. In contrast, BCG vaccination should be postponed to later stages of life (> 12 months).

Finally, children born to mothers with positive anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB antibodies, regardless of whether they are related to disease developed by the mother, may present with neonatal lupus.

As mentioned above, this point will not be addressed in this protocol, only the following will be considered in general:

- •

The most common neonatal involvement will be cutaneous. This is a transient process and photoprotection of the exposed areas of the child is recommended.

- •

Cardiac involvement in the form of atrioventricular block, although its prevalence ranges between 1%–2% of pregnancies, can increase to 20% in the case of second pregnancies of mothers with an affected first child. As this is a particularly serious condition, pregnant mothers who are positive for these antibodies should be monitored by an obstetric risk unit for early detection and treatment if they develop. If this does not occur during foetal development, the baby should be followed up until the age of one year by paediatrics/paediatric rheumatology/paediatric cardiology as it could begin during this period.

This protocol attempts to standardise the follow-up of patients from the time of pregnancy desire until the infants' first year of life. We believe that it may be useful as a basis for all rheumatology consultations for patients with chronic inflammatory diseases of childbearing age. The limitations of this protocol are the relative lack of methodological soundness of the recommendations, given that they come from a multidisciplinary working group, but it could serve as a basis for future protocols and the changes that occur in the guidelines, and therefore, always assess that there have been no changes in the technical data sheets or international guidelines of drugs. It is important to test patients of childbearing age and to use drugs that are compatible with pregnancy. If necessary, the patient should be assessed in specialist units. Multidisciplinary assessment of these patients is essential for their management (rheumatology, gynaecology, and paediatrics).

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.