Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is characterized by the autonomous production of parathyroid hormone (PTH), in which there is hypercalcemia or normal-high serum calcium levels in the presence of elevated or inappropriately normal serum PTH concentrations.

Exceptionally in symptomatic patients, a diagnosis can be established on the basis of clinical data. PHPT must always be evaluated in patients with clinical histories of nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, osseous pain, subperiosteal resorption, and pathologic fractures, as well as in those with osteoporosis–osteopenia, a personal history of neck irradiation, or a family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome (types 1 or 2).

Diagnosis of PHPT is biochemical. Asymptomatic hypercalcemia without guiding signs or symptoms is the most frequent manifestation of the disease. For differential diagnosis, PTH must be measured, as well as phosphate, chloride, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, 1,25 dyhidroxyvitamin D and calcium-to-creatinine clearance.

The diagnosis and differential diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism will be discussed here.

El hiperparatiroidismo primario (HP) es una entidad clínica que se caracteriza por la producción autónoma de parathormona (PTH), en la cual hay hipercalcemia o calcio sérico normal-alto, con valores de PTH elevados o inapropiadamente normales.

De forma excepcional, el diagnóstico puede establecerse a partir de la clínica en pacientes sintomáticos. El HP siempre debe ser tenido en cuenta en pacientes con historia de cálculos renales, nefrocalcinosis, dolor óseo, fracturas patológicas, resorción subperióstica o en aquéllos que presenten osteoporosis-osteopenia, antecedentes de irradiación en cuello o historia familiar de neoplasia endocrina múltiple tipo 1 o 2.

El diagnóstico del HP es bioquímico, siendo la hipercalcemia asintomática la manifestación más frecuente de la enfermedad. Para el diagnóstico diferencial, además de la PTH, debe medirse el fósforo, cloro, 25 hidroxivitamina D, 1,25 dihidroxivitamina D y calciuria.A continuación, se revisa el diagnóstico y se detallan los cuadros clínicos con los que se debería plantear el diagnóstico diferencial.

Primary hyperparathyroidism (HP) is a disease characterized by autonomous production of parathyroid hormone (PTH), in which there is hypercalcemia, or high-normal serum calcium with elevated serum PTH or inappropriately “normal” calcium.

HP occurs in about 1% of the adult population, but affects more than 2% of it after 55 years, being 2–3 times more common in women than in men.

The most common cause is a parathyroid adenoma (80%–85% single and double in about 4%). The remaining cases are due to hyperplasia of the parathyroid glands, or, more rarely, a parathyroid carcinoma.

Familiar forms of HP are uncommon, manifesting usually as part of multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN), with very rare forms of presentation, primary hyperparathyroidism and familial neonatal hyperparathyroidism.

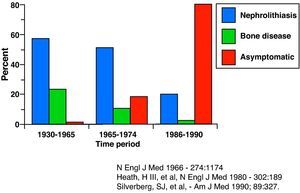

Clinical ManifestationsFrom the description of the disease in the 1930s by Albright and Reifenstein,1 clinical expression has changed considerably2 (Fig. 1).

The first clinical descriptions regarded it as an uncommon disease with significant morbidity, which usually involved bone or renal disease, or both.3

Currently, due to increased use of biochemical markers, the most frequent clinical form (88%) is a mild and asymptomatic hypercalcemia with serum calcium about 1mg/dL above normal. However, HP may present more floridly or as asymptomatic subclinical forms.1,4

Skeletal ManifestationsDue to its predominantly cortical bone expression, PTH excess can lead to osteitis fibrosa cystica (2% of cases), manifested as bone pain and fractures. The typical radiographic signs include subperiosteal resorption of the middle and distal phalanges, thinning of the distal clavicles, a mottled or “salt and pepper” skull pattern, bone cysts and brown tumors in the long bones and pelvis.5–7

Renal ManifestationsNephrolithiasis or nephrocalcinosis can be observed in approximately 20% of patients with HP. About 5% of nephrolithiasis are secondary to HP, while the majority are due to calcium oxalate by hipercalciuria.8,9

The most frequent finding, however, is hypercalciuria (35%–40% of cases) due to an increased filtered load of calcium, which exceeds the reabsorption capacity.

Some patients will only have decreased creatinine clearance and renal impairment.

Gastrointestinal ManifestationsMay present as anorexia, nausea, vomiting and constipation. Peptic ulcer is rare (unless it occurs in the context of a MEN 1). Likewise, acute pancreatitis is rarely seen due to hypercalcemia associated with HP.10

Neuromuscular ManifestationsMuscle weakness and fatigue, intellectual fatigue, mental disturbances, and in rare cases that present with severe hypercalcemia, coma.11,12

Cardiovascular ManifestationsHP has been associated with hypertension. Hypercalcemia can also cause ECG changes such as shortening of the QT, blockages or increased sensitivity to digitalis.

In the classical forms, myocardial, valvular and vascular calcifications were described in HP. Today, stiffness and a decreased vascular ventricular13 index can be seen.

DiagnosisGiven the nonspecific clinical and practical absence of symptoms, the diagnosis is established by laboratory studies.

In the differential diagnosis screening, apart from calcium and PTH, the values of phosphorus, chlorine, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and creatinine corrected urinary calcium in 24h urine 10 should be determined.

The diagnosis of HP is confirmed when hypercalcemia or corrected calcium is in the high-normal range in the presence of elevated or inappropriately normal PTH.14,15 Other laboratory data to consider are: serum phosphorus, which tends to be low or in the lower limits of normal, calciuria, which is elevated in 40% of patients, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, which is usually lower than normal and may be associated with severe disease, and metabolic acidosis with hyperchloremia secondary to an inhibition of bicarbonate reabsorption by PTH, as well as increased markers of bone turnover.14,15

Differential DiagnosisDifferential diagnosis should be established with the following entities.

MalignancyIt is important to note that HP and malignancies are the 2 most common causes of hypercalcemia (90%).10

In addition, malignancy-associated hypercalcemia is the most prevalent cause of hypercalcemia in hospitalized patients, being serious and rapidly evolving, as it is often linked to advanced stage malignancies, and therefore a poor prognosis.

In hypercalcemia of malignancy, PTH is suppressed (except in the rare cases of PTH-producing tumors where it is elevated), and along with the clinical data, points at the diagnosis10,16 (Table 1).

Familial Hypocalciuric HypercalcemiaIt is a familial syndrome with autosomal dominant inheritance, a consequence of a mutation that inactivates one allele of the calcium sensing receptor in parathyroid glands in the renal17 tubule.

It is asymptomatic young adults, with mild hypercalcemia and PTH in the normal range or slightly elevated being the only laboratory findings.

There is no need for its treatment.17,18

The way to differentiate this clinical entity of HP consists of documenting a low urinary calcium in 24h urine, and decreased calcium/creatinine clearance ratio14,15,19–21 (Table 2).

DrugsTwo drugs that deserve special consideration when evaluating a patient with hyperparathyroidism are thiazide diuretics and lithium.

- -

Hypercalcemia due to thiazide diuretics10,22: they reduce renal calcium excretion and may cause some mild hypercalcemia. Should be removed whenever possible because can mask an HP; reassess the patient at 3 months.

- -

Hypercalcaemia due to Lithium: Lithium may also reduce urinary calcium excretion, leading to hypocalciuria and hypercalcemia, and in a small percentage of patients, elevation of PTH.

The pattern to be followed is the same way, stop treatment if possible and reassess at 3 months.16

Normocalcemic Primary HyperparathyroidismIt has been hypothesized whether this entity represents the first phase of HP or if it is a different disease characterized by an alteration in the regulation of PTH secretion, or a state of relative resistance to the action of PTH.23,24

It represents an incidental finding in a patient studied for decreased bone mineral density (BMD).

Must be differentiated from secondary (SH), and essential hyperparathyroidism to determine the values of vitamin D.

It requires close monitoring in order to detect symptomatic disease.25

Secondary HyperparathyroidismClinical situation in which the parathyroid glands respond well to low extracellular calcium concentration (renal failure, poor intake, malabsorption, etc.). However, if the increase in PTH cannot correct the plasma calcium, either due to a disorder in the organs responsible for transportation or deficiencies, hypocalcemia develops. Therefore, HS may be associated with calcium concentrations that are within or below the reference range.

Laboratory findings show high or normal PTH with low calcium levels or within normal limits.

It is very important to measure levels of vitamin D and 24-h urinary calcium, in order to make the differential diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency leading to HP.26

HS treatment is to correct the primary abnormality that caused hypocalcemia.

Table 3 details the root causes of HS.

Causes of Secondary Hyperparathyroidism.

| 1. Renal failure |

| Alteration in calcitriol production |

| Hyperphosphatemia |

| 2. ↓ intake of Ca |

| 3. Ca malabsorption |

| Vitamin D deficiency |

| Bariatric surgery |

| Celiac disease |

| Pancreatic disease (fat malabsorption) |

| 4. Renal calcium loss |

| Idiopathic hypercalciuria |

| Loop diuretics |

| 5. Inhibition of bone resorption |

| Biphosphonates |

| Hungry bone syndrome |

Faced with an elevation of PTH, measurement of serum calcium, and subsequently, calciuria in 24h urine is required. If the latter is normal, this suggests a normocalcemic HP. If, however, it is elevated, HP will be very likely.

In cases where calciuria is reduced, reposition of vitamin D should be carried out before levels of serum calcium and PTH are measured. If these values are normalized, the picture is compatible with hypovitaminosis D. HS If, however, they remain high, this points to an HP with vitamin D deficiency (Fig. 2 and Table 4).

Normocalcemic HP/HP With Vitamin D Deficiency/HS Due to Hypovitaminosis D.

| PTH | Blood Calcium | Urine Calcium | Vitamin D | |

| HP normocalcemic | High | Normal or high | Normal | Normal |

| HP with vitamin D deficiency | High | Normal | Normal-low or low | Low (<20) |

| HS with vitamin D deficiency | High | Normal or low | Low | Low (<20) |

HP, primary hyperparathyroidism; HS, secondary hyperparathyroidism; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

The daily requirement for vitamin D is 800–1000U/day.

It is noteworthy that about 90% of patients with HP have, at least, insufficient vitamin D levels.

Treatment consists in supplementing and maintaining vitamin D levels above 30ng/ml, strictly controlling the values of calcemia, calciuria, and phosphatemia and to monitor the numbers of vitamin D every 3–6 months.14,15,19,20

Treatment of Primary HyperparathyroidismIf symptomatic, surgery is the treatment of choice.

If the patient is asymptomatic, management is more controversial, and in any case, should be monitored to detect any disease progression.

Current recommendations are established as the annual measurement of serum calcium and creatinine, as well as performing a bone density test every 1–2 years.21

Please, cite this article as: Martínez Cordellat I. Hiperparatiroidismo: ¿primario o secundario? Reumatol Clin. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.reuma.2011.06.001.