Inclusion body myositis is a idiopathic inflammatory myopathy characterized by muscle weakness and dysphagia, with muscle biopsy showing inflammation and rimmed vacuoles. We present the case of a patient who was diagnosed with polymyositis but due to lack of response to treatment, a new biopsy revealed inclusion body myositis.

La miositis por cuerpos de inclusión es una miopatía inflamatoria idiopática caracterizada por debilidad muscular, disfagia y biopsia muscular con inflamación y vacuolas ribeteadas. Presentamos el caso de una paciente a la que se le diagnosticó polimiositis pero que por falta de respuesta al tratamiento se le realizó una nueva biopsia que reveló miositis por cuerpos de inclusión.

Inclusion body myositis (IBM) is an immune-mediated disease affecting muscles and internal organs.1 Prevalence rates vary from 24.8 to 45.6 per million.2 It affects individuals over the age of 503 and debuts with musculoskeletal damage to the volar aspect of the forearm, flexors of the fingers and quadriceps, resulting in asymmetrical muscle weakness and inclusion bodies on biopsy.4 Biochemically, they are accompanied by elevated creatine phosphokinase (CPK), the presence of anti-cytosolic 50-nucleotidase cN1A antibody in up to 30% of cases, which, though non-specific, are associated with increased severity and mortality, and biopsy reveals an endomysial inflammatory exudate with infiltration of inflammatory cells in non-necrotic muscle fibres and vacuoles rimmed by membranous cytoplasmic material, atrophic fibres, and intra- or extravacuolar congophilic inclusions.3

We report the case of a female patient diagnosed with polymyositis (PM) on the basis of elevated CPK, positive AC-1 antibodies, electromyography (EMG) with myopathic pattern, and muscle biopsy with inflammatory infiltrate, with poor response to steroid treatment. A new biopsy was therefore carried out that demonstrated IBM.

Case ReportAn 82-year-old female presented difficulty climbing stairs and swallowing, diminished muscle strength in the shoulder girdle and pelvis, elevated CPK levels, and was positive for AC-1 antibodies at the age of 66. Anti-Jo1 immunospecificity was subsequently assessed and was negative (Table 1). An EMG examination was conducted that evidenced myopathic pattern and a biopsy of the left deltoid muscle was performed with the patient’s informed consent and endomysial lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate was noted. The woman was diagnosed with MP and treatment was instituted with prednisone and methotrexate, with a subsequent change to mycophenolate mofetil.

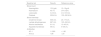

Baseline laboratory values of the patient with inclusion body myositis.

| Baseline lab | Results | Reference value |

|---|---|---|

| Blood count | ||

| Haemoglobin | 13.2 g/dL | 12–18 g/dL |

| Haematocrit | 40.1% | 37%–52% |

| Leukocytes | 3.4 K/UL | 4.5–10 K/UL |

| Platelets | 252 K/UL | 150–250 K/UL |

| Blood chemistry | ||

| Creatinine kinase | 936 UI/L | 24–170 U/L |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 867 UI/L | 123–245 U/L |

| Alanine transferase | 61 U/L | 13–40 U/L |

| Aspartate transferase | 59 U/L | 9–36 U/L |

| Antibodies | ||

| AC-1 | 1:1280 | < 1:80 |

| Anti-Jo | 1;98 | < 20 |

Her disease progressed and she required the use of a cane and wheelchair; she experienced difficulty in extending the fingers of the left hand, atrophy of the long flexor muscles of the fingers, predominantly the left one, and quadriceps. Muscle testing (MMT8/ MMT26 manual muscle assessment procedures) yielded a score of 116 of 150 and 194 of 260, respectively, at the expense of distal muscle involvement. The new muscle biopsy indicated the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate with rimmed vacuoles and IBM was diagnosed (Fig. 1).

Muscle biopsy from this case.

Modified trichrome Gomori (TMG) staining. Close-up 200× TMG, staining demonstrated muscle fibres of varying size, ballooning, aggregates of inflammatory cells with focal invasion of some muscle fibres, and substantial proliferation of connective tissue (A). Close-up 400× TMG, with obvious nuclear centralisation (arrow) (B). Close-up 400× MTG Vacuoles rimmed with granular material and filaments (star) classically observed in this pathology (C).

Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Close-up 100×, panoramic view of the biopsy displaying a major deviation from the general architecture, with enlarged spaces and substitution by connective tissue, fibre morphology with bulging and inflammatory infiltrate (D). Close-up at 400× (H&E) illustrates the inflammatory infiltrate surrounding the muscle fibre in greater detail (E), as well as abundant connective tissue.

This case initially featured symmetrical proximal muscle weakness, dysphagia, and elevated CPK, as well as an endomysial lymphocytic infiltrate, characteristic of PM.5 Nonetheless, recurrence of elevated CPK values, increased proximal muscle weakness and distal involvement, asymmetric atrophy of the hand and quadriceps muscles, deterioration of the patient’s dysphagia, and her poor response to treatment led to IBM2 being suspected. Alamr et al. reported that 14% of 367 patients with IBM had an atypical onset and of them, 6% displayed proximal arm weakness at the time of onset.6 In a clinical case series of IBM with no rimmed vacuoles on biopsy, diagnosis was delayed for up to eight years following symptom debut7; however, this feature may be absent in 20% of all cases.8 The condition that imitates IBM most closely is PM, inasmuch as its serology is similar and antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are positive in 15-19% in IBM and 60% in PM.9 A retrospective study comparing several subtypes of inflammatory myopathies failed exhibit any significant difference between PM and IBM with respect to follow up, disease duration, clinical characteristics, and CPK values.10 In fact, the presence of PM has currently been called into question, as most individuals diagnosed with PM are re-classified as suffering from anti-synthetase syndrome having no rash, immune-mediated necrotising myopathy, or IBM with or without rimmed vacuoles ribeteadas.3,11

The clinical course in this case evidences the challenge posed by the differential diagnosis between PM and IBM, which entails a delay in establishing the diagnosis.

ConclusionThe clinical evolution with asymmetrical muscle involvement and poor response to immunosuppressants made it possible to reformulate the diagnosis as IBM, with a slowly progressive course as well as histopathological changes in muscle biopsies. Treatment with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants failed to stem the progression of the disease.

FundingNo external funding was necessary. The resources of the Hospital de Especialidades Centro Médico Nacional, La Raza were used.