Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disease with articular and extra-articular manifestations. Mortality in RA is influenced by an increased risk of cardiovascular events by up to 48% (RR: 1.48, 95% CI 1.36–1.62), with a higher standardized mortality rate (SMR) due to cardiovascular causes compared to the general population. Our main objective was to examine the effect of clinical and serological variables on the risk of major cardiovascular events (MCE) in a cohort of RA patients.

Materials and methodsThis was a retrospective cohort study. Patients more tha 18 years old and active follow-up in the RA care models of Hospital Universitario Clínica San Rafael and Clínica Nogales were included. Patients with prior major cardiovascular events or polyautoimmunity syndromes before the RA diagnosis were excluded. Survival analysis was performed to evaluate the probability of remaining free of MCEs, along with Cox proportional hazards analysis and structural equation modeling using a PATH analysis to assess direct and indirect effects.

ResultsA total of 406 patients were included, 342 (84%) of whom were women, with a mean age of 44.8±13.1 years and a disease duration of 13±13.4 months. The average DAS28 activity score was 2.5±1.78, with 48.7% having active disease (DAS28>2.6). Nineteen patients experienced MCEs, resulting in a cumulative incidence (CI) of 4.68% (4.4% myocardial infarction and 1.4% stroke). The most frequent risk factors were hypertension (23.7%) and smoking (24.8%). Bivariate analysis showed that heart failure (RR=1.58, 95% CI 1.12–2.23, p=0.01), and hypertension (RR=2.36, 95% CI 1.22–4.60, p<0.01) were significantly associated with MCEs. The probability of MCE-free survival at six months post-diagnosis was 50%. In the Cox model, only hypertension and age at diagnosis were significantly associated with MCE outcomes. In the PATH analysis, dyslipidemia was significantly associated with myocardial infarction without a mediating effect from corticosteroids (coef=1.83, p<0.001).

ConclusionTraditional risk factors increase the risk of MCEs in RA patients. Additionally, dyslipidemia acts as an independent risk factor without mediation by other variables, making it a therapeutic target for preventing these outcomes.

La artritis reumatoidea (AR) es una enfermedad autoinmune sistémica con manifestaciones articulares y extraarticulares. La mortalidad en AR está determinada por el incremento de riesgo de eventos cardiovasculares hasta en un 48% (RR: 1.48 IC95% 1,36 – 1,62), con aumento de tasa de mortalidad estandarizada (TME) por causas cardiovasculares comparada con la población general. Nuestro objetivo general fue examinar el efecto de las variables clínicas y serológicas sobre el riesgo de ECM en una cohorte de pacientes con AR.

Materiales y métodosEstudio de cohorte retrospectivo. Se incluyeron pacientes mayores de 18 años, con seguimiento activo en los modelos de atención para pacientes con AR del Hospital Universitario Clínica San Rafael y Clínica Nogales, los pacientes con evento cardiovascular mayor previos al diagnóstico de AR y con síndromes de poli autoinmunidad fueron excluidos. Se realizó análisis de supervivencia para evaluar la probabilidad libre de eventos cardiovasculares mayores, análisis de riesgos proporcionales cox y modelamiento de ecuaciones estructurales a partir de un análisis PATH para evaluar efectos directos e indirectos.

Resultados406 pacientes fueron incluidos, 342 (84,%) mujeres, media de edad 44,8±13,1 años, tiempo de evolución de enfermedad de 13±13,4 meses, promedio de la calificación de DAS28 2,5±1,78, el 48,7% enfermedad activa con DAS28>2,6. Desenlace de ECM se presentó en 19 pacientes con una incidencia acumulada (IA) de 4,68% (4,4% IAM y 1,4% ACV). Factores de riesgo más frecuentes fueron hipertensión arterial (23,7%), tabaquismo (24,8%). En el análisis bivariado, se encontró que la insuficiencia cardiaca (RR=1,58 IC95% 1,12 – 2,23 p=0,01), edad al diagnóstico (54,8 versus 44,3 p<0,01) e hipertensión arterial (RR=2,36 IC95% 1,22 – 4,60 p<0,01) se asociaron significativamente con ECM. La probabilidad de supervivencia libre de ECM del 50% fue a seis meses desde el diagnostico, en el modelo cox solo las variables hipertensión y edad al diagnóstico fueron significativamente asociados a este desenlace. En el análisis PATH, la dislipidemia fue asociada significativamente a infarto agudo de miocardio sin efecto mediador de los glucocorticoides (coef=1.83, p<0.001).

ConclusiónLos factores de riesgo tradicionales incrementan el riesgo de ECM en los pacientes con AR, así mismo la dislipidemia se comporta como un factor de riesgo independiente sin mediación de otras variables, lo que constituye un objetivo terapéutico para la prevención de estos desenlaces.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disease with joint and extra-articular manifestations. It occurs globally, with an estimated prevalence of .46%,1 and in Latin America, the prevalence ranges from .25% to .36% in the central and Andean regions, respectively.2 Mortality in RA is determined by an increased risk of cardiovascular events of up to 48% (RR: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.36–1.62), in addition to an increase in the standardised mortality rate (SMR) from cardiovascular causes compared to the general population.3

This increased risk may be influenced by traditional risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, obesity, and diabetes. These factors may be more prevalent in patients with RA,4 although they do not fully explain the increased cardiovascular risk associated with RA. However, some serological markers related to the inflammatory response in RA have a significant linear correlation with cardiovascular risk markers, such as carotid artery intima-media thickness.5 This suggests that the inflammatory response plays a role in endothelial dysfunction and that this population group is more predisposed to cardiovascular events due to the effect of non-traditional risk factors attributable to the disease.

Chronic inflammation not only promotes the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, but also increases their risk of rupture. There are mechanisms involved at the cellular level, related to the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-18 and IL-33, increased oxidative stress, and the activation of NADPH oxidases, leading to increased lipid peroxidation and dysfunction.6

Traditional and non-traditional risk factors related to inflammatory markers of RA contribute to an increased risk of major cardiovascular events (MACE), such as acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and stroke (CVA). Predicted risk increases proportionally to the number of factors present. Therefore, patients with three or more risk factors have a MACE incidence rate of 7.49 per 1,000 patients per year.7

The use of immunosuppressive therapies may also modify these risk factors, as some may temporarily raise lipid levels, thereby increasing the risk for MACE. However, a direct effect of C-reactive protein (CRP) on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels was observed when these variables were explored through a mediation analysis using structural equation modelling (SEM). This increase was independent of the response to treatment in the mediation analysis.8

Given the increased risk for MACE in RA and their association with multiple subrogated risk factors in RA that increase the prediction of cardiovascular events in models with traditional factors, our overall objective was to examine the effect of clinical and serological variables on the risk of MACE in a cohort of RA patients, and to describe the probability of MACE-free survival and analyse the factors associated with lower MACE-free survival using proportional hazards analysis. Finally, we evaluated an SEM model to measure the direct and indirect relationships between traditional and non-traditional risk factors for the development of MACE based on a path analysis.

Materials and methodsA retrospective cohort study was conducted using clinical records from two hospitals in Bogotá D.C. (Colombia). Information was collected from the medical records of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of RA, according to the 1987 classification criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR).9 The cohort consisted of patients who began clinical follow-up in rheumatology services between 2019 and 2024, and the analysis was performed retrospectively on previously recorded data without any intervention or prospective follow-up. The dates of RA diagnosis were identified, and retrospective follow-up was performed in the records until the occurrence of the first MACE, or until June 2024 in cases without MACE. The cohort is closed, and no new patients were included after the inclusion cut-off date.

MACE (outcome variable) was defined according to the fourth definition of MI as the presence of acute myocardial injury detected by abnormal cardiac biomarkers in the setting of acute myocardial ischaemia.10 Stroke was defined as an acute episode of focal neurological dysfunction that persists for more than 24h and caused by a blockage or rupture of a blood vessel, leading to restricted blood flow to the brain, according to the American Heart Association (AHA).11 The independent (predictive) variables included traditional risk factors such as diabetes mellitus (DM), age, smoking, dyslipidaemia, and hypertension (HTN).

Patients over 18 years of age who were being actively followed up in the care models for RA patients at the Hospital Universitario Clínica San Rafael and Clínica Nogales, and who had been diagnosed according to the 1987 ACR classification criteria, were included. Patients with a MACE prior to RA diagnosis and with poly-autoimmune syndromes, defined as the presence of RA+systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, or systemic sclerosis were excluded. The Hospital Universitario Clínica San Rafael’s research ethics committee approved this protocol.

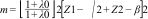

Statistical analysisSimple random sampling was conducted. The sample size n was calculated using the formula for calculating the risk rate12: n=m/μ, where:

The study by Lauper et al. (2018)13 was used as a reference. It detected a risk rate of .0026 for an alpha error (type 1) of .05, a beta error (type 2) of .20, a power of 80%, and a probability of occurrence of .09. It was estimated that a minimum of 7.8 events would need to be identified with a sample size of 84 patients. For the descriptive analysis, qualitative variables were described in terms of their absolute and relative frequencies. The Shapiro–Wilk (SW) normality test was applied to the quantitative variables, which were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD) if the distribution was normal, or the median and interquartile range if it was not symmetrical. The χ2 test was used to evaluate the association between qualitative variables, with the effect size measured by the relative risk (RR) and a 95% confidence interval. A p-value of less than .05 was considered significant. For the survival analysis, time-to-event S(t) was taken as the survival function and event-free survival probability was estimated using Kaplan–Meier curves. The log-rank test was used to evaluate differences in MACE-free survival between groups. In the multivariate analysis, the dependent variable was time of MACE-free survival, and the predictors were the clinical, serological, and therapeutic characteristics of the patient group. This was performed using a Cox proportional hazards model. To adjust the model, Schoenfeld residuals were evaluated, and the proportionality assumption was assessed.

To evaluate the relationships between traditional and non-traditional risk factors, SEM modelling based on a path model was used. Due to the nature of the observable variables included in the theoretical model, the model was first identified and specified. Then, the coefficients were evaluated, and then goodness-of-fit measures were calculated: root mean square error approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index/Tucker–Lewis index (CFI/TLI), and standardised root mean square residual (SRMR). R Studio version 4.3.2 was used for the analysis and MPLUS version 8.11 for the SEM modelling

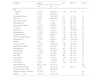

ResultsA total of 406 patients were included in the study. Of these, 342 (84%) were women. The mean age of the patients was 44.8±13.1 years, the median disease duration was 13±13.4 months, and the mean DAS28 activity score was 2.5±1.78, 48.7% had active disease, defined as a DAS28 score >2.6. Serologically, 88.4% of the patients were seropositive for rheumatoid factor (RF) and 78.3% for anti-CCP. The MACE endpoint occurred in 19 patients, with a cumulative incidence (CI) of 4.68% at a median follow-up period of 13 months. Of the patients who experienced the outcome of interest, 4.4% had an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and 1.4% had a stroke. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors were evaluated, and hypertension was the most frequently found condition at 23.7%, followed by smoking at 24.8%. Dyslipidaemia and diabetes were both present in 9.1% of patients (Table 1).

Characteristics of the population.

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 342 (84.2) |

| Male | 64 (15.7) |

| Age at diagnosis, (SD) | 44.8 (13.1) |

| Progression time in months, (IQR) | 13 (17.4) |

| DAS28, (IQR) | 2.5 (1.78) |

| BMI, (IQR) | 25.6 (6.3) |

| Rheumatoid factor | 349 (88.4) |

| Anti-CCP | 318 (78.3) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 18 (4.4) |

| Stroke | 6 (1.4) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 10 (2.4) |

| Dry syndrome | 59 (14.5) |

| Rheumatoid nodules | 65 (16) |

| Smoking | 101 (24.8) |

| Hypertension | 111 (27.3) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 37 (9.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 37 (9.1) |

| Heart failure | 8 (1.9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (1.2) |

| Major cardiovascular event | 19 (4.6) |

| DAS28>2.6 | 175 (48.7) |

| Glucocorticoids >10mg/day | 217 (53.4) |

| Methotrexate | 287 (70.4) |

| Leflunomide | 221 (54.4) |

| Sulfasalazine | 72 (17.7) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 60 (14.7) |

| Anti-TNFα | |

| Etanercept | 27 (6.7) |

| Certolizumab pegol | 13 (3.2) |

| Golimumab | 2 (.5) |

| Infliximab | 1 (.2) |

| Adalimumab | 5 (1.2) |

| Tocilizumab | 12 (2.9) |

| Rituximab | 32 (7.8) |

| JAK inhibitor | 11 (2.7) |

BMI: body mass index; age: mean (standard deviation); n (%): number of patients (relative frequency); IQR: interquartile range; duration of disease: median (interquartile range); SD: standard deviation.

In the bivariate analysis, heart failure (RR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.12−2.23; p=.01), age at diagnosis (54.8 versus 44.3; p<.01), and hypertension (RR: 2.36; 95% CI: 1.22−4.60; p<.01) were significantly associated with MACE (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis.

| Variable | MACE | RR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 13 (3.8) | 329 (96.1) | 1.24 | .91−1.69 | .10 |

| Male | 6 (9.3) | 58 (90.6) | |||

| Rheumatoid factor | 14 (4) | 335 (95.9) | .41 | .18−.91 | .08 |

| Anti-CCP | 12 (3.7) | 306 (96.2) | .57 | .31−1.06 | .17 |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 3 (30) | 7 (70) | 1.17 | .96−1.42 | .16 |

| Dry symptoms | 3 (5) | 56 (95) | 1.02 | .83−1.24 | 1.0 |

| Rheumatoid nodules | 3 (4.6) | 62 (95.3) | 1.0 | .82−1.22 | 1.0 |

| Smoking | 9 (8.9) | 92 (91.0) | 1.45 | .94−2.23 | .09 |

| Heart failure | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1.58 | 1.12−2.23 | .01* |

| Dyslipidaemia | 4 (10.8) | 33 (89.1) | 1.16 | .92−1.46 | .14 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (10.8) | 33 (89.1) | 1.16 | .92−1.46 | .14 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | 1.40 | .94−1.16 | .57 |

| Hypertension | 13 (3.2) | 98 (24.1) | 2.36 | 1.22−4.60 | <.01* |

| Obesity | 1 (2) | 9 (98) | .91 | .72−1.50 | .85 |

| Glucocorticoids | 12 (5.5) | 205 (94.4) | 1.28 | .70−2.23 | .38 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 5 (8.3) | 55 (91.6) | 1.16 | .89−1.53 | .26 |

| Sulfasalazine | 3 (4.1) | 69 (95.8) | .98 | .80−1.19 | 1.0 |

| Methotrexate | 14 (4.8) | 273 (95.1) | 1.12 | .52−2.41 | .76 |

| Leflunomide | 11 (4.9) | 210 (95) | 1.09 | .63−1.86 | .75 |

| Anti-TNF | 2 (5) | 46 (95) | .98 | .84−1.15 | 1.0 |

| Tocilizumab | 1 (8.3) | 11 (91.6) | 1.03 | .92−1.14 | 1.0 |

| Anti-CD20 | 1 (3.1) | 31 (96.8) | .97 | .87−1.08 | 1.0 |

| JAK inhibitor | 2 (18.1) | 9 (81.9) | 1.09 | .93−1.27 | .15 |

| Age at diagnosis | 54.8 (11.08) | 44.3 (13) | <.01* | ||

| Over 50 years of age | 12 (8.7) | 125 (91.2) | .51 | .35−.74 | <.01* |

| Under 50 years of age | 7 (2.6) | 262 (97.3) | |||

| Disease duration in months | 24 (121) | 13 (16) | .06 | ||

| DAS28>2.6 | 3.16 (16.1) | 2.45 (1.75) | .60 | ||

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular event; RR: relative risk.

The variable "age at diagnosis" was dichotomised into those under and over 50 years of age, showing that patients under 50 years old had a significantly lower risk of MACE (RR: .51; 95% CI: .35−.74; p<.001).

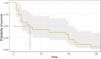

Survival analysis showed a 50% probability of remaining MACE-free at 6 months after RA diagnosis (Table 3) (Fig. 1). Among the different groups of variables, patients with obesity were significantly less likely to remain MACE-free; however, in patients with disease activity with a DAS28>2.6, although they were less likely to remain MACE-free, this difference was not significant (Fig. 2).

Probability of major cardiovascular event-free survival.

| Time (months) | Number of patients at risk | Number of events | Probability of survival | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 | 3 | .8421 | .69−1.0 |

| 2 | 16 | 2 | .7368 | .56−.96 |

| 3 | 14 | 3 | .5789 | .39−.55 |

| 5 | 11 | 1 | .5263 | .34−.80 |

| 6 | 10 | 1 | .4737 | .29−.76 |

| 7 | 9 | 1 | .4211 | .24−.71 |

| 13 | 8 | 1 | .3684 | .20−.76 |

| 19 | 7 | 1 | .3158 | .16−.61 |

| 20 | 6 | 2 | .2105 | .08−.50 |

| 22 | 4 | 1 | .1579 | .05−.44 |

| 23 | 3 | 1 | .1053 | .02−.39 |

| 28 | 2 | 1 | .0526 | .00−.35 |

| 33 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

In the proportional hazards analysis, event-free survival time was used as the dependent variable, with traditional risk factors as well as those related to disease activity and the serological profile of RA, considered as predictors. The results showed that HTN reduces the probability of MACE-free survival by 82%. Furthermore, the probability of MACE-free survival increased significantly by 8% for each additional year of age at the time of RA diagnosis (Table 4). Model adjustment showed a Schoenfeld’s global test value of .62 (Fig. 3).

For the SEM analysis, a theoretical model was first proposed based on two observed dependent variables: AMI and stroke. The predictor variables that could explain these two outcomes were traditional risk factors such as hypertension, age, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus (DM), smoking, and non-traditional factors such as DAS28 and disease duration. The variables dyslipidaemia and corticosteroids could be correlated, as could the two dependent variables (Fig. 4).

The model was identified as ”over-identified”, containing 78 pieces of information and 23 estimated parameters. The coefficients were evaluated, showing a significant association between dyslipidaemia and AMI in the structural model (coef: .75; OR: 2.6; p=.03) (Table 5). However, no coefficient showed a significant association with stroke. The dependent variables, AMI and stroke, showed a significant correlation (coef: .55; p=.001) (Fig. 5). The model showed adequate overall goodness of fit with an RMSEA<.05 and incremental fit measures (CFI, TLI) greater than .95.

Regression coefficients of the model (path analysis).

| AMI | Coefficient | p-value | CVA | Coefficients | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | .409 | .268 | Sex | –.364 | .819 |

| Age | .016 | .152 | Age | .043 | .303 |

| RR | –.191 | .648 | RF | .822 | .561 |

| Anti-CCP | –.177 | .571 | Anti-CCP | –1.837 | .058 |

| GC | .294 | .401 | GC | –.048 | 1 |

| DAS28 | –.024 | .842 | DAS 28 | .005 | .983 |

| Smoking | –.008 | .28 | Smoking | .015 | .35 |

| Hypertension | .254 | .458 | Hypertension | .25 | .783 |

| Dyslipidaemia | .757 | .035* | Dyslipidaemia | .882 | .521 |

| Diabetes mellitus | .113 | .774 | Diabetes mellitus | –.079 | .933 |

AMI: acute myocardial infarction; CVA: stroke; GC: glucocorticoids; RF: rheumatoid factor.

In the mediation analysis between dyslipidaemia and AMI, using corticosteroid use as a mediating variable, a significant direct effect (c′) was observed between dyslipidaemia and AMI (coef: 1.83; p<.001). However, no indirect effect mediated by the use of glucocorticoids (ab) was observed (coef: .06; p=.23) (Fig. 6).

Mediation analysis. X: dlp: dyslipidaemia; Y: AMI: acute myocardial infarction; Z: gc: glucocorticoid moderator variable. a: coefficient between predictor variable dyslipidaemia (X) and moderator variable glucocorticoids (Z); b: effect between moderator variable (Z) and outcome acute myocardial infarction (Y); c`: direct effect of dyslipidaemia (X) on acute myocardial infarction (Y) without the mediation of glucocorticoids; ab: indirect effect of dyslipidaemia (X) on acute myocardial infarction (Y) with the mediation of glucocorticoids (Z).

Major cardiovascular outcomes in RA patients have been reported in different cohorts with varying results. In our study, the cumulative incidence of MACE for a cohort of 406 patients was 4.68% at a median follow-up of 13 months. Bridal et al. (2020) evaluated the risk of MACE at 10 years of follow-up at 7.3%, which increases substantially to 12% in patients with RA and a history of coronary heart disease.14 However, few local studies have evaluated the frequency of these events associated surrogated risk factors for RA.

In our analysis, the traditional risk factors most frequently identified were hypertension, smoking, and dyslipidaemia. However, these factors do not fully explain the increased predisposition to MACE, despite being reported more frequently in patients with RA. Argnani et al. (2021) reported a higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes in RA patients than in healthy individuals, as well as a higher risk of myocardial infarction and stroke.15 These adverse outcomes may be related to the inflammatory burden characteristic of the disease, which makes them more prevalent in patients with extra-articular manifestations.

In Colombia, few studies have evaluated the prevalence of these events in patients with RA and extra-articular involvement. However, Ortega-Hernández et al. (2008) describe a higher proportion of patients with hypertension and thrombosis in the group with extra-articular expression.16 This variable remained a predictor of higher cardiovascular risk in the multivariate analysis of the same study.

In our study, HTN was the most common comorbidity, and was also associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events and an 82% lower probability of MACE-free survival. Similar findings were reported in a cross-sectional, descriptive study in Colombia by Bautista et al. (2016), who found a hypertension prevalence of 20.4%. However, this could be explained by the included population's average age.17 Age-related changes, in turn, promote vascular ageing and increase the risk of comorbidity.

In our research study, age emerged as a significant protective factor for MACE in the bivariate analysis, demonstrating a 49% reduction in risk among individuals under 50 years of age. However, in the multivariate model, this variable increased the probability of event-free survival by 8% for each year since diagnosis. This could be related to shorter disease durations and, therefore, lower inflammatory burdens. As a traditional risk factor for cardiovascular events, age is closely related to changes associated with endothelial cell senescence, telomere shortening, oxidative stress, and oncogenic activation.18 Other modifiable factors, such as smoking, may be related to higher cardiovascular morbidity.

Of the patients in our study 24% were smokers, and smoking was also associated with a non-significant increase in cardiovascular risk. In patients with RA and current smokers, the risk of cardiovascular events increases by up to 50%.19 However, smoking cessation and non-smoking reduced the risk of MACE by up to 30% and 52%, respectively,20 although this predictive variable was not retained in the multivariate analysis in this study. Notably, other manifestations related to extra-articular expression were also associated with the outcome of interest.

Pulmonary involvement in RA was one of the most common extra-articular manifestations of MACE. Although not statistically significant, the impact of pulmonary fibrosis (PF) of autoimmune aetiology on cardiovascular disease, and especially on coronary heart disease, has been increasing in terms of prevalence due to shared risk factors and outcomes, to the point of theorising whether PF is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease. On this point, a retrospective case-control study by Sinha et al. (2024) found a higher prevalence of coronary heart disease in hospitalisations for PF due to increased lipoxygenases, which leads to the accumulation of low-density lipoproteins (LDL) in the endothelium.21

This study found that dyslipidaemia was significantly associated with AMI in the SEM analysis as a factor that directly and significantly explained this outcome. However, no indirect or mediating effect of glucocorticoids was identified, which suggests that lipid levels may be related to the inflammatory activity that is characteristic of RA. In states of inflammation and re-inflammation, serum lipid values change, decreasing circulating levels of LDL, HDL, and apolipoproteins (ApoAI). This is known as the ”lipid paradox” in patients with inflammation, as these levels, which do not appear to be found in plasma, are found distributed in other cellular pathways such as the endothelium, elevated cytokines and tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor (TGF-β), alter the function of molecules that convert specific and efficient forms of HDL.22

Hyperlipidaemia as an independent risk factor is not an unusual phenomenon. Diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, and RA share this problem, characterised by an increased cardiovascular risk. The antioxidant activity of HDL depends on the levels of ApoA1 present on its surface. The displacement of this molecule from the lipoprotein contributes to poor HDL performance, favouring oxidative processes.23

In patients with RA, the presence of serum amyloid A has been shown to displace these proteins, reducing ApoA1 and ApoA2 levels. Additionally, there is an increase in the coupling of HDL with other oxidative molecules, such as myeloperoxidase (MPO) and haptoglobin, which exacerbates oxidative damage.23

The limitations of this study are related to the retrospective nature of the data collection and the small number of patients included. These patients are part of comprehensive RA care programmes, which could explain the low rates of inflammatory activity and the underestimation of the extra-articular and cardiovascular manifestations of this disease. Furthermore, DAS28 values were not stratified given that a higher proportion of patients had controlled disease, with a mean value of 2.5 (SD: 1.78).

In our cohort, it was found that more than half of the patients had doses >10mg/day of prednisolone. It should be noted that this was not an inclusion criterion, but rather a baseline characteristic recorded retrospectively. As the use of high doses of glucocorticoids can influence cardiovascular risk, this factor was considered in the multivariate analysis models to adjust for possible confounding effects in the path analysis. This data may reflect the therapeutic behaviour of the participating centres, which is a limitation for generalising the results to other populations with different therapeutic approaches.

This research study has the advantage of being the only one in our field to use SEM methods to evaluate direct and indirect effects based on mediation analysis with respect to the outcome of MACE in this RA patient population. Furthermore, the innovative multivariate analysis provides data on cumulative incidence and factors associated with MACE, enabling the identification of intervention points for estimating future mortality prediction scales independently of traditional risk factors in the Colombian RA population.

The finding of dyslipidaemia as an independent predictor of AMI in our research, without the mediation of other indirect factors, constitutes a key aspect as a therapeutic target in the overall control of the disease and prevention of morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular causes.

ConclusionTraditional risk factors increase the risk of MACE in RA patients, and dyslipidaemia acts as an independent risk factor without the mediation of other variables. This constitutes a therapeutic target for the prevention of these outcomes.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.