Neonatal lupus erythematosus is an infrequent disease seen in newborns. It is caused by transplacental maternal autoantibody passage. Cutaneous involvement and congenital heart block (CHB) are the most common affections, although it may involve multiple organs such as the liver, lungs, blood, nervous or digestive systems.

This article present a review of the four cases diagnosed in the past five years in a Neonatal Unit, which shows the different clinical spectrum which can develop around this disease (CHB, multisystemic affection and two cutaneous cases), different autoantibodies (specially anti-SSA) with an early negativization during the first year of life and the possibility of future collagen vascular disease as occurred in one case.

El lupus eritematoso neonatal es una enfermedad rara del recién nacido producida por el paso transplacentario de autoanticuerpos maternos. Las 2 formas de presentación más frecuentes son la dermatológica (lupus eritematoso subagudo) y el bloqueo auriculoventricular completo (BAVC). También puede producir afectación hematológica, hepática, neurológica, respiratoria y digestiva.

Presentamos una revisión de 4 casos diagnosticados en los últimos 5 años en nuestra Unidad de Neonatología, que reflejan el amplio espectro clínico con el que se puede presentar esta enfermedad (un caso de BAVC, uno con afectación multisistémica y 2 casos con expresión cutánea), los diferentes patrones de autoanticuerpos (con un predominio de anticuerpos anti-SSA), la desaparición de autoanticuerpos en todos los casos antes del año de edad y la posibilidad de aparición de colagenopatías en el futuro, como ocurrió en uno de nuestros casos.

NL is a rare disease with an estimated incidence of 1/10 000-20 000 in newborns (NB) and predominantly females. It occurs due to transplacental passage of maternal IgG autoantibodies, usually anti-Ro (SSA) (95%), anti-La (SSB) and less frequently anti-U1RNP. A case was recently been described in our country caused by anti-Sm. Although it can affect multiple organs, the 2 most common clinical forms are dermatological involvement (subacute lupus erythematosus), present in 50% of cases, and complete atrioventricular block (CAVB), found in 50% of NB. Both coexist only in 10% of cases.1,2

Other cases present with hepatic, hematological, neurological, respiratory, and digestive manifestations, which usually subside before one year of age, coinciding with the disappearance of maternal autoantibodies. Conversely, CAVB becomes chronic in most cases, meriting an early pacemaker.3–5

NL diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and the absence of a family history makes it difficult. Only 50% of mothers present connective tissue disease symptoms at diagnosis, particularly systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or Sjögren's syndrome. The rest, though asymptomatic, are at risk of developing it in the future.1–3

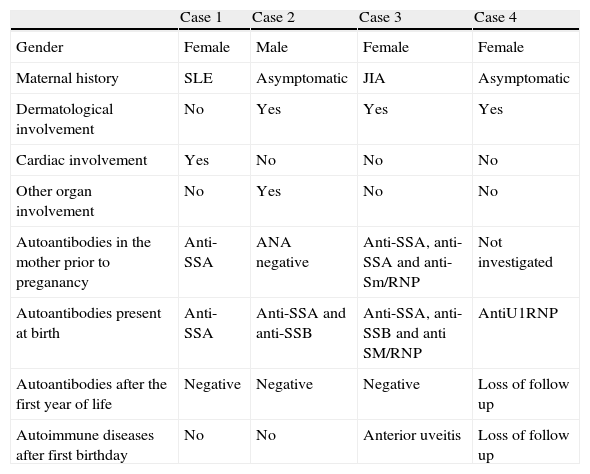

We present a review of 4 cases diagnosed in the last 5 years in our Neonatal Unit (Table 1).

Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Female |

| Maternal history | SLE | Asymptomatic | JIA | Asymptomatic |

| Dermatological involvement | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cardiac involvement | Yes | No | No | No |

| Other organ involvement | No | Yes | No | No |

| Autoantibodies in the mother prior to preganancy | Anti-SSA | ANA negative | Anti-SSA, anti-SSA and anti-Sm/RNP | Not investigated |

| Autoantibodies present at birth | Anti-SSA | Anti-SSA and anti-SSB | Anti-SSA, anti-SSB and anti SM/RNP | AntiU1RNP |

| Autoantibodies after the first year of life | Negative | Negative | Negative | Loss of follow up |

| Autoimmune diseases after first birthday | No | No | Anterior uveitis | Loss of follow up |

Female RN diagnosed in the first trimester of CAVB. Mother with SLE and Evans syndrome with positive anti-SSA antibodies in treatment during pregnancy with dexamethasone 4mg/day.Because of possible complications, she was delivered at a referral hospital, where she underwent a pacemaker placement at birth with good outcome. She had no skin lesions or systemic involvement, although anti-SSA autoantibodies were positive. Follow up was conducted without further connective tissue disease manifestations appearance to date, in which the patient is 4 years old.

Case 2Black male NB admitted with respiratory distress and skin lesions. Obstetric history: second pregnancy, uneventful. Normal childbirth at week 36+2. Apgar 8/10. Weight: 2.040g. Length: 44cm. Head circumference: 31.5cm. Family history: mother, 26, a native of Senegal, followed for chronic hepatitis B, anemia and mild leukopenia, and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were negative. Two years before she had presented hyperpigmented skin lesions on the left cheek, self-limited, without receiving a diagnosis.

Clinical examination showed scaly erythematous brownish plaques on the skin on the face, with periocular mask distribution, as well as on the ears, scalp, trunk and upper extremities (Figs. 1 and 2). Mild tachypnea without distress, and good bilateral ventilation. Abdomen with hepatomegaly 1cm and splenomegaly 2cm below the rib margin. Neurologically, hyperexcitable with trembling and mild generalized hypertonia and hyperreflexia.

Laboratory tests showed: thrombocytopenia (19,000mm−3), leukopenia (4290mm−3) and hemolytic anemia: (Hb7.6g/dl, hematocrit 23%, reticulocytes 2%, haptoglobin: 6.63mg/dl). A blood smear presented intense anisocytes, poikylocytes, and some teardrop schistocytes. There was mild hypertransaminasemia mild (glutamicoxalacetic transaminase 119U/l; glutamic pyruvic transaminase 62U/l). Normal ECG. Normal chest radiograph. A transfontanelar ultrasound showed a hyperechoic white matter, doubtful microcalcifications and scattered foci of bleeding at the level of the germinal matrix. MRI showed discrete alteration of the white matter, indicating incipient encephalomalacia changes. Skin biopsy showed mild hyperkeratosis, minimal epidermis basal layer vacuolar changes and abundant mucin deposition in the dermis. Positive ANA, speckled pattern, title 1/1280. Anti-SSA and anti-SSB positive, anticardiolipin, anti-native DNA, anti-Sm and anti-Sm/RNP were negative.

With the diagnosis of NL with cutaneous, hematologic, respiratory, hepatic and neurological involvement, treatment was initiated with topical corticosteroids and tacrolimus. For the hematological manifestations, the patient required treatment with gamma globulin at 4g/kg and intravenous corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 2mg/kg/day with subsequent reduction, maintained for 53 days) and transfusion of packed red blood cells and irradiated platelets. He required oxygen for 21 days. At discharge the patient presented Hb 10.1g/dl, leukocytes 8400mm−3 and 307,000mm−3 platelets.

At 2 months, erythematous annular lesions with central necrosis of a discoid lupus type reappeared on the trunk and extremities, with atrophy and scar hyperpigmentation, which resolved at 4 months of age. Hematologic abnormalities were normalized after 2 months. ANA were negative at 8 months of life.

Currently, the patient is 3 years of age and continues monitoring without evidence of connective tissue disease and presenting only residual scars on cutaneous lesions (Fig. 3).

Case 3This case was one month old and came to the emergency department with dermatosis. Personal history: first pregnancy, uneventful. Eutocic delivery at week 40. Apgar 9/10. Weight at birth: 2650g. Length: 48cm. Head circumference: 33cm. Family history: mother with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, subsequently diagnosed with SLE, who presented prior to pregnancy positive anti-SSA, anti-SSB and anti SM/RNP antibodies >1/1.280.

On examination there were circinate erythematous brownish plaques on the scalp and face. Laboratory: ANA positive with a speckled nuclear pattern, 1/1.280. Anti-SSA, anti-SSB and anti SM/RNP antibodies were positive. Normal ECG. With the diagnosis of cutaneous NL the patient received topical treatment with corticosteroids and sodium borate, with good results. Negative ANA before the one year birthday.

At age 4 the patient was diagnosed with bilateral acute anterior uveitis. ANA was positive with a speckled nuclear pattern, 1/320. Anti-SSA and anti-SSB were positive, anti-Sm/RNP negative. The patient had a poor response to topical (corticosteroids and cycloplegics) and systemic treatment (corticosteroids1mg/kg/day and methotrexate 10mg/m2/week), being controlled with subcutaneous adalimumab. During the treatment of uveitis, the patient presented knee arthritis, which resolved with ibuprofen.

Case 4This case was a month old and, from one week of life, coinciding with the start of mixed lactation, began with skin lesions, rejection of milk, vomiting and diarrhea. Personal history: controlled gestation. Cesarean section at term. Family history: mother with apparently no history of collagen disease, even after the diagnosis of her daughter NL was investigated, although she was found to have Raynaud's phenomenon that had not been previously studied.

Physical examination showed annular erythematous plaques, with a lighter center and atrophic appearance, which started in the face, and were confluent at that level, with subsequent extension to the trunk and limbs (Figs. 4 and 5). Erosions in the labial mucosa and palmoplantar involvement. Skin biopsy showed a chronic perivascular and interstitial infiltrate in the superficial dermis with minimal and focal lymphocytic exocytosis. Laboratory: ANA were positive with a speckled nuclear pattern, 1/1.280. Anti-SSA and anti-SSB were negative, with positive anti-Sm. IgE specific to cow milk protein was positive. Normal ECG. With the diagnosis of NL and protein allergy to cow's milk, treatment was initiated with topical corticosteroids and protein hydrolyzate. The patient returned to his home country, without coming to a follow up, making it impossible to determine the possible occurrence of later connective tissue disease.

NL can occur in children of mothers with SLE, Sjögren's syndrome or other collagen vascular diseases. Approximately half of the mothers are asymptomatic at diagnosis and only have positive anti-Ro2 antibodies. It is important to know that the healthy mothers of these children are at high risk of developing a connective tissue disorder in the future and that the probability of recurrence is 20% in3 successive pregnancies.

Although the pathogenesis is unknown, placental transfer of antibodies is essential.1,4

The transient nature of the manifestations along with the disappearance of antibodies in children, supports this hypothesis. However, the presence of autoantibodies is necessary but not sufficient. There is even a discordance between twins, so it is assumed that there are unknown factors that make some children susceptible to the presence of maternal autoantibodies.4

Skin lesions, although they may be present at birth, usually occur in the first weeks of life, sometimes after sun exposure or phototherapy. Typical lesions are reminiscent of those of subacute lupus erythematosus and consist of an erythematous annular morphology. Sometimes they are manifested as periocular mask-like “raccoon eyes” erythema. The most common sites are the face and scalp, probably because they are exposed areas. They tend to resolve spontaneously within one year, coincident with clearance of maternal antibodies, and usually do not leave a scar, but occasionally hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation may persist, which usually heals in months or years 4.

Treatment consists of photoprotection, topical corticosteroids and possibly low power laser on residual telangiectasias.1,6

The characteristic cardiac disturbance of NL is the CAVB, which is the most serious clinical manifestation due to its irreversibility and because it has a high rate of mortality and morbidity, requiring a permanent pacemaker in most patients who survive. The risk of cardiac involvement in the mother's first child if positive anti-Ro are present is 1%–2% and recurrence in a second child is 18%.6 Currently, the effectiveness of intravenous immunoglobulin as a prophylaxis of CAVB in at risk pregnancies (mothers who already have children with NL) is under study and monitoring with fetal echocardiography is indicated from the 16th week of gestation in all mothers with anti-Ro positive antibodies.1,7

The prognosis of the disease is marked by cardiac involvement, as the other manifestations are mostly transient and self resolved.6

Long term follow up is essential as patients are at an increased risk of developing autoimmune diseases in later childhood or adulthood2,6 as has happened in one of our cases in whom, after the disappearance of the maternal autoantibodies, self produced autoantibodies were found leading to a connective tissue disorder.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors state that no experiments were performed on persons or animals for this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors state that they have followed their workplace protocols regarding the publication of patient data and all patients included in the study have received enough information and have given their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors state that they have obtained informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in this article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Porcel Chacón R, Tapia Ceballos L, Díaz Cabrera R, Gutiérrez Perandones MT. Lupus eritematoso neonatal: revisión de casos en los últimos 5 años. Reumatol Clin. 2014;10:170–173.