Eosinophilic fasciitis is an uncommon scleroderma-like disease of unknown etiology. It was first described by Shulman in 1974, and is characterized clinically by a subcutaneous induration and its development predominantly in the limbs.1 Eosinophilia is detected in peripheral blood in 80% of the patients, and more than 50% present with hypergammaglobulinemia.2

Case ReportWe report the case of a 45-year-old man, with nothing remarkable in his medical record, who presented with a 6-month history of thickening and induration of upper and lower limbs, which had an important functional impact on his activities of daily living. The patient participated in sports, but recalled no noteworthy injuries or other possible triggering factor.

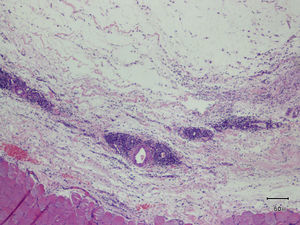

Aside from the above-mentioned induration, the physical examination revealed furrows along the length of the veins of the superficial plexus, a phenomenon classically referred to as the “groove sign”. On the other hand, the skin on extensor surfaces was shiny, erythematous and edematous, with marked follicular orifices, which gave it the appearance of an “orange peel” or “peau d’orange” (Figs. 1 and 2). Full-thickness skin biopsy disclosed thickening of the muscle fascia, together with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells and scattered eosinophils (Fig. 3). Laboratory tests revealed blood eosinophilia with a count of 1000cells/mm3. With a diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis, treatment was begun with prednisone at a dose of 1mg/kg/day and, later, with methotrexate. The signs and symptoms improved progressively over the following months.

The diagnosis of eosinophilic fasciitis is based mainly on a histological study, requiring a full-thickness skin biopsy that includes muscle fascia. However, knowledge of the forms of clinical presentation is necessary to establish diagnostic suspicion.3 The groove sign is a highly specific finding, and is often accompanied by “peau d’orange”. It consists of furrowing along the length of the veins of the superficial plexus, which becomes more marked when the limb is raised. It is thought to be due to the fact that, as the epidermis and superficial dermis are not affected, they maintain their elasticity and, thus, they are depressed upon the collapse of the superficial veins, which are surrounded by inflamed, fibrotic tissue.4

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lloret-Ruiz C, Beneyto-Florido M, Barrado-Solís N, Miquel-Miquel J. Piel de naranja y signo del surco. Reumatol Clin. 2016;12:228–229.