Interstitial lung diseases associated with systemic autoimmune diseases (ILD-SAD) can progress to a fibrotic form that can benefit from antifibrotic treatment. The aim of the study is to describe a cohort of patients with ILD-SAD who manifest progressive pulmonary fibrosis treated with antifibrotics.

MethodsSingle-centre retrospective observational study from a tertiary care hospital on a cohort of patients with ILD-SAD with progressive pulmonary fibrosis evaluated in a joint pulmonology and rheumatology clinic that initiated treatment with antifibrotic drugs between 01/01/2019 and 01/12/2021. Clinical characteristics were analysed. The evolution of pulmonary function test and adverse effects during treatment were described.

Results18 patients were included. The mean age was 66.7 ± 12.7 years, with a higher frequency of females (66.7%). Systemic sclerosis (SS) was the most frequent systemic autoimmune disease (36.8%). The majority of patients were receiving systemic glucocorticoid treatment (88.9%), 72.2% of patients were receiving treatment with disease-modifying drugs, the most frequent being mycophenolate mofetil (38.9%), and 22.2% with rituximab. Functional stability was observed after the start of antifibrotic treatment. Two patients died during follow-up, one due to progression of ILD.

ConclusionOur study suggests a beneficial effect of antifibrotic treatment added to immunomodulatory treatment in patients with fibrotic ILD-SAD in real life. In our cohort, patients with ILD-SAD with progressive fibrosing involvement show functional stability after starting antifibrotic treatment. Treatment tolerance was relatively good with a side effect profile similar to that described in the medical literature.

Las enfermedades pulmonares intersticiales difusas asociadas a enfermedades autoinmunes sistémicas (EPID-EAS) pueden presentar una progresión fibrótica. El objetivo principal del estudio es describir una serie de casos de pacientes con EPID-EAS que cursan con fibrosis pulmonar progresiva e inician tratamiento con fármacos antifibróticos.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo unicéntrico de un hospital de tercer nivel sobre una serie de casos de pacientes con EPID-EAS con fibrosis pulmonar progresiva valorados en una consulta conjunta de neumología y reumatología, que iniciaron tratamiento con fármacos antifibróticos entre 01/01/2019 y 01/12/2021. Se analizaron las características epidemiológicas, clínicas, funcionales, radiológicas y terapéuticas al inicio del tratamiento, y la evolución funcional durante el tratamiento, así como los efectos adversos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 18 pacientes. La edad media observada fue de 66.7 ± 12.7 años con mayor frecuencia de sexo femenino (66.7%), siendo la esclerosis sistémica la enfermedad autoinmune sistémica más frecuente (36.8%). La mayoría de los pacientes se encontraban con tratamiento con glucocorticoides sistémicos (88.9%), un 72.2% de pacientes con fármacos modificadores de la enfermedad, siendo el más frecuente el micofenolato mofetilo (38.9%), y un 22.2% con rituximab. Se observó una estabilidad funcional tras el inicio del tratamiento con antifibrótico. Fallecieron dos pacientes durante el seguimiento, uno como consecuencia de la progresión de la enfermedad intersticial pulmonar.

ConclusiónNuestro estudio sugiere un efecto beneficioso del tratamiento antifibrótico añadido al tratamiento inmunomodulador en pacientes con EPID-EAS fibrótica en vida real. En nuestra serie de casos, los pacientes con EPID-EAS con afectación fibrosante progresiva muestran una estabilidad funcional tras el inicio del tratamiento antifibrótico. La tolerancia al tratamiento fue relativamente buena, con un perfil de efectos secundarios similar al descrito en la literatura médica.

Diffuse interstitial lung disease associated with systemic autoimmune disease (ILD-SAD) has a variable course and prognosis, being the leading cause of mortality in systemic sclerosis (SS) and the second leading cause of mortality in rheumatoid arthritis (RA)1,2. A significant percentage of these patients develop progressive fibrosing involvement, which has a major impact on disease progression3. In recent years, two clinical trials have been published demonstrating the efficacy and safety of nintedanib treatment in patients with fibrosing ILD associated with SS and SAD4,5. However, there is a lack of data on real-life patients, providing data on use in clinical practice, as well as efficacy and tolerability in a broader group of patients. The main objective of the study is to describe a case series of patients with ILD-SAD with progressive pulmonary fibrosis treated with antifibrotic drugs.

Material and methodsSingle-centre retrospective observational single-centre study in a tertiary hospital.

The study included patients with progressive fibrosing disease in a joint pulmonology and rheumatology consultation who started treatment with antifibrotic drugs between 01/01/2019 and 01/12/2021. Patients with SAD were included according to the diagnosis made by rheumatology and according to international classification criteria6. Patients who did not meet criteria for a defined SAD, but met criteria for interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) according to ATS/ERS criteria7 were also included.

ILD-SAD was defined by the presence of lung images suggestive of ILD on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) according to international classificatory criteria. Progressive disease was considered a ≥10% reduction in forced vital capacity (FVC), a ≥15% reduction in carbon monoxide diffusion capacity (DLCO) or a 5%–10% reduction in FVC associated with worsening respiratory symptoms and/or fibrosis on chest CT, all within the previous 24 months.

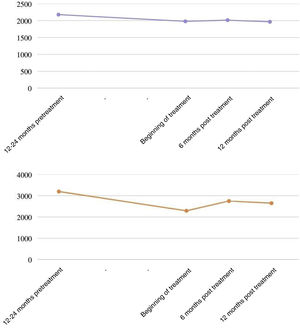

Epidemiological, clinical, radiological and therapeutic characteristics at baseline were assessed. In addition, functional respiratory tests prior to the start of treatment (12–24 months before), as well as at baseline and at 6 and 12 months of follow-up were evaluated. Evolution was analysed according to the percentage change from the theoretical value in FVC and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Side effects occurring during antifibrotic treatment, as well as changes in dosage and discontinuation of the drug are described.

These data were obtained retrospectively by review of electronic medical records.

Qualitative variables are expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

ResultsEighteen patients were included. The mean age observed was 66.7 ± 12.7 years, with a higher frequency of the female sex (66.7%) and no tobacco contact (66.6%). The demographic characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. SS was the most frequent systemic autoimmune disease (38.9%). A radiological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) or probable UIP was present in 55.5% of patients. At the time of initiation of antifibrotic treatment, most patients were on systemic glucocorticoids (88.9%). Some 72.2% of patients were on disease-modifying drugs, the most frequent being mycophenolate mofetil (38.9%), and 22.2% were on rituximab. Since the start of antifibrotic therapy, two patients discontinued mycophenolate treatment (one due to adverse effects and one due to disease progression), and started treatment with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, respectively. In addition, one patient added tocilizumab treatment for control of the underlying disease (RA) and for inflammatory progression of interstitial lung disease.

Baseline characteristics.

| Age (years) | 66.7 ± 12.7 |

| Sex (women) | 12 (66.6%) |

| Tobacco habit | |

| Never | 12 (66.6%) |

| Ex smokers | 6 (33.4%) |

| Lung hypertension | 1 (5.6%) |

| Radiological pattern | |

| UIP/probable UIP | 10 (55.5%) |

| Others | 8 (44.5%) |

| Autoimmune disease | |

| Systemic sclerosis | 7 (38.9%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4 (22.2%) |

| IPAF | 4 (22.2%) |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | 2 (11.1%) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1 (5.6%) |

| Immunosupressant therapy | |

| Glucocorticoids | 16 (88.9%) |

| Hydroxycholoroquine | 2 (11.1%) |

| Leflunomide | 1 (5.6%) |

| Methotrexate | 1 (5.6%) |

| Azatioprin | 2 (11.1%) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 8 (44.4%) |

| Rituximab | 4 (22.2%) |

IPAF: Interstitial Pneumonia with autoimmune features; UIP: Usual interstitial pneumonia.

The antifibrotic used in all cases was nintedanib (100%). The mean follow-up time from the start of nintedanib was 417.4 ± 172.7 days. In the lung function study, mean pre-treatment, baseline, 6-month and 12-month FVC of 2,176 ± 714 mL, 1,978 ± 375 mL, 2,012 ± 622 mL and 1. 964 ± 530 mL, respectively (Fig. 1); and a mean DLCO of 3.195 ± 976 mmol/kPa/min, 2.292 ± 932 mmol/kPa/min, 2.750 ± 939 mmol/kPa/min, 2.651 ± 1.409 mmol/kPa/min, respectively. Two patients had functional deterioration during the 12 months after initiation of antifibrotic therapy (≥10% reduction in FVC and/or ≥15% reduction in DLCO). This drug required dose reduction in 7 patients (38.9%) and was discontinued in 3 patients due to gastrointestinal side effects (15.8%), with a median time to drug discontinuation of 177 days. No hepatic toxicity side effects were reported. Two deaths occurred during follow-up: one was related to progression of interstitial lung disease, the other died at home, probably related to a recent diagnosis of stage IV lung neoplasia.

DiscussionIdiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is the most studied progressive interstitial disease. However, other non-ILDs, which are different from IPF are also at risk of developing progressive fibrosing disease, including ILD-SADs secondary to pathologies such as SS, RA, idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, Sjögren's syndrome or IPAF8. In the INBUILD study5, patients with fibrotic progression were defined as those with progression in the previous 24 months, defined as a decrease in FVC of at least 10%, or a decrease in FVC between 5 and 10% with worsening respiratory symptoms or increased fibrosis on HRCT, or a combination of worsening respiratory symptoms and worsening fibrosis on HRCT. More recent are the international clinical recommendations on the management of progressive pulmonary fibrosis other than IPF, which include patients with progressive fibrosing disease in patients with ILD-SAD. This clinical guideline establishes the definition of progressive pulmonary fibrosis in those patients with non-IPF type ILD if two of the following criteria are met: 1) symptomatic worsening; 2) functional worsening understood as an absolute drop ≥5% in FVC or ≥10% in DLCO in one year of follow-up; 3) evidence of radiological progression. Similarly, these new recommendations suggest the use of nintedanib as antifibrotic treatment in this patient profile once pharmacological treatment for the underlying disease has been optimized9.

In the case of ILD-SAD, the evidence for immunosuppressive drugs for the treatment of lung involvement comes from clinical trials in SS10,11 as well as from observational studies in the rest of SAD12,13. In addition, the SENSCIS study14 also found that patients treated with mycophenolate and nintedanib had an additional benefit in decreasing FVC decline compared to patients taking mycophenolate alone, with a similar adverse effect profile. However, there is currently no established consensus on the appropriate immunosuppressive therapy prior to initiating antifibrotic therapy. Therefore, an individualised assessment of each patient must be made, for which a multidisciplinary approach is essential.

Regarding the limitations of our study, it is an observational study with a small sample size and the patients received different immunosuppressive treatments, which makes it difficult to extrapolate results. Given the small number of patients, subgroup analyses could not be performed. Nevertheless, our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first study in clinical practice to include patients with ILD-SAD and progressive fibrotic lung disease on nintedanib treatment with the same side effects as those described in clinical trials. In addition, patients were evaluated in a standardised manner in a joint rheumatology and pulmonology practice, with a relatively long follow-up time after initiation of antifibrotic therapy (mean 15.7 months).

ConclusionIn our study, patients with ILD-SAD and progressive fibrosing interstitial involvement show relative functional stability after initiation of antifibrotic therapy. Adverse effects were similar to those reported in clinical trials, with gastrointestinal effects being the most frequent.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.