The difficulty in diagnosis and the spectrum of clinical manifestations that can determine the choice of treatment for antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) has fostered the development of recommendations by the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER), based on the best possible evidence. These recommendations can serve as a reference for rheumatologists and other specialists involved in the management of APS.

MethodsA panel of 4 rheumatologists, a gynaecologist and a haematologist with expertise in APS was created, previously selected by the SER through an open call or based on professional merits. The stages of the work were: identification of the key areas for the document elaboration, analysis and synthesis of the scientific evidence (using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, SIGN levels of evidence) and formulation of recommendations based on this evidence and formal assessment or reasoned judgement techniques (consensus techniques).

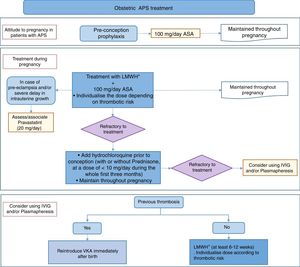

ResultsForty-six recommendations were drawn up, addressing 5 main areas: diagnosis and evaluation, measurement of primary thromboprophylaxis, treatment for APS or secondary thromboprophylaxis, treatment for obstetric APS and special situations. These recommendations also include the role of novel oral anticoagulants, the problem of recurrences or the key risk factors identified in these subjects. This document reflects the last 25, referring to the areas of: obstetric APS and special situations. The document provides a table of recommendations and treatment algorithms.

ConclusionsUpdate of SER recommendations on APS is presented. This document corresponds to part II, related to obstetric SAF and special situations. These recommendations are considered tools for decision-making for clinicians, taking into consideration both the decision of the physician experienced in APS and the patient. A Part I has also been prepared, which addresses aspects related to diagnosis, evaluation and treatment.

La dificultad para el diagnóstico y la variedad de manifestaciones clínicas que pueden determinar la elección del tratamiento del síndrome antifosfolípido (SAF) primario ha impulsado a la Sociedad Española de Reumatología (SER) en la elaboración de recomendaciones basadas en la mejor evidencia posible. Estas recomendaciones pueden servir de referencia para reumatólogos y otros profesionales implicados en el manejo de pacientes con SAF.

MétodosSe creó un panel formado por 4 reumatólogos, una ginecóloga y una hematóloga, expertos en SAF, previamente seleccionados mediante una convocatoria abierta o por méritos profesionales. Las fases del trabajo fueron: identificación de las áreas claves para la elaboración del documento, análisis y síntesis de la evidencia científica (utilizando los niveles de evidencia de SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network) y formulación de recomendaciones a partir de esta evidencia y de técnicas de «evaluación formal» o «juicio razonado».

ResultadosSe han elaborado 46 recomendaciones que abordan 5 áreas principales: diagnóstico y evaluación, medidas de tromboprofilaxis primaria, tratamiento del SAF o tromboprofilaxis secundaria, tratamiento del síndrome antifosfolípido obstétrico y situaciones especiales. Está incluido también el papel de los nuevos anticoagulantes orales, el problema de las recurrencias o los principales factores de riesgo identificados en estos individuos. En este documento se reflejan las últimas 25, referidas a las áreas de: SAF obstétrico y situaciones especiales. El documento contiene una tabla de recomendaciones y algoritmos de tratamiento.

ConclusionesSe presentan las recomendaciones de la SER sobre SAF. Este documento corresponde a la parte 2.ª relacionada con el SAF obstétrico y las situaciones especiales. Estas recomendaciones se consideran herramientas en la toma de decisiones para los clínicos, teniendo en consideración tanto la decisión del médico experto en SAF como la opinión compartida con el paciente. Se ha elaborado también una parte I que aborda aspectos relacionados con el diagnóstico, evaluación y tratamiento.

There are a total of 46 recommendations regarding primary antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). They cover 5 main areas: diagnosis and evaluation, primary thromboprophylaxis, the treatment of primary APS or secondary thromboprophylaxis, the treatment of obstetric APS and special situations. The document covers the final 25 of these recommendations, in the areas of obstetric APS and special situations (Table 1).

SER recommendations for primary antiphospholipid syndrome (part 2).

| Treatment of obstetric APS | GR |

|---|---|

| Recommendation: the use of acetylsalicylic acid at a dose of 100mg/day prior to conception is suggested for all patients with obstetric APS who wish to become pregnant, maintaining this dose throughout pregnancy | C |

| Recommendation: in patients with obstetric APS as a secondary prophylactic treatment it is recommended to add low molecular weight heparin to the acetylsalicylic acid at the moment pregnancy is confirmed, maintaining this throughout gestation. The dose of heparin should be individualised according to the risk of each patient | C |

| Recommendation: in refractory obstetric APS the conventional treatment recommends commencing hydrochloroquine before pregnancy and maintaining this throughout gestation, alone or combined with prednisone or equivalent from the start of pregnancy (≤10mg/day during the first three months) | D |

| Recommendation: in patients who develop complications associated with placental insufficiency (pre-eclampsia or delayed intrauterine growth) in spite of the conventional treatment, the recommendation is to add pravastatin (20mg/day) from the start of the complication | C |

| Recommendation: it is not recommended to use intravenous immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis at first, although they may be considered if there is no response to other treatments | √ |

| Recommendation: in previously anticoagulated patients with thrombotic APS vitamin K antagonists should be re-introduced immediately after birth | √ |

| Recommendation: in women with obstetric APS it is recommended that after birth thromboprophylaxis should be administered using low molecular weight heparin at a prophylactic dose during at least 6 weeks | √ |

| Recommendation: in patients with thrombotic APS who for any reason are not receiving long-term anticoagulation thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin is recommended at intermediate doses, individualised the dose according to risk during at least 6–12 weeks after giving birth | D |

| Recommendation: in patients with APS who are going to undergo assisted reproduction techniques individualisation according to risk is recommended, associating low molecular weight heparin as the anticoagulant of choice at prophylactic or therapeutic doses | D |

| Recommendation: patients with APS who are taking oral anticoagulation should switch to a therapeutic dose of low molecular weight heparin before ovary stimulation and continue with this during the whole pregnancy | D |

| Recommendation: patients with APS without chronic anticoagulation are advised to receive treatment with acetylsalicylic acid at an antiaggregant dose and low molecular weight heparin, at an individualised dose, from the start of ovary stimulation and to maintain this throughout gestation | D |

| Recommendation: in women with antiphospholipid antibodies and triple positivity or high levels of APA, due to the risk of thrombosis as well as the appearance of obstetric complications the use of low molecular weight heparin plus acetylsalicylic acid is recommended. | D |

| Recommendation: the recommendation is to avoid ovary hyperstimulation syndrome, as this is a risk factor for thrombosis secondary to assisted reproduction techniques, by using low risk hormonal protocols for this complication | D |

| Recommendation: the recommendation is to monitor patients with isolated obstetric APS after pregnancy the puerperium as they have a higher risk of thrombosis than the general population | C |

| Recommendation: the recommendation is to individualise cardiovascular risk in the said monitoring (by identifying the presence of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, smoking or dyslipidemia, etc.) and informing, eliminating or controlling existing cardiovascular risk factors | B |

| Recommendation: during follow-up the advice on using low-dose acetylsalicylic acid as primary antithrombotic prophylaxis should be individualised. There is no conclusive evidence as to whether it should only be administered to the patients with the highest thrombotic risk (those who are positive for lupus anticoagulant or patients with triple antibody positivity) | B |

| Recommendation: the recommendation is to use subcutaneous low molecular weight in situations with a high risk of venous thrombosis | √ |

| Special situations | |

|---|---|

| Recommendation: rigorous control of anticoagulation is recommended before and after the transplant of a solid organ, especially in the case of kidney transplant | √ |

| Recommendation: routine screening is recommended for antiphospholipid antibodies before the transplant of a solid organ in all patients with a history of thromboembolic events | √ |

| Recommendation: thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin is recommended in patients with a high risk serological profile and neoplasia, especially in situations with increased thromboembolic risk (surgery, catheter implantation or the start of chemotherapy) | √ |

| Recommendation: the recommendation is to suspend anticoagulation in case of moderate to high risk invasive procedures or a high risk of haemorrhage, and to perform bridging therapy | D |

| Recommendation: the recommendation is to use low molecular weight heparin as bridging therapy, at an individualised dose adjusted for weight and kidney functioning, suspending it at least 24h before the invasive procedure | D |

| Recommendation: in pregnant patients with APS who use low molecular weight heparin at a therapeutic or intermediate dose, the recommendation is to suspend this at least 24h before giving birth or other procedures. During birth it is not necessary to suspend the treatment in patients who are using acetylsalicylic acid at a dose of 100mg | D |

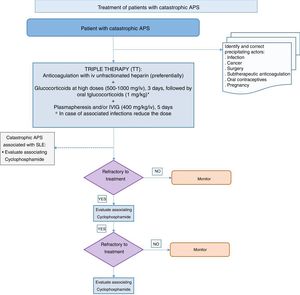

| Recommendation: in a patient with catastrophic APS the initial treatment must include what is known at triple therapy, which includes: anticoagulation, preferentially with intravenous unfractionated heparin, associated with high doses of glucocorticoids, plasmapheresis and/or intravenous immunoglobulin | D |

| Recommendation: in cases that are refractory to triple therapy adding rituximab or eculizumab may be considered | D |

APA: antiphospholipid antibodies; GR: grade of recommendation (see Appendix 1).

Which treatments are the most effective in a patient with obstetric APS?

Recommendation: it is suggested that acetylsalicylic acid be administered prior to conception at a dose of 100mg/day in all patients with obstetric APS who wish to become pregnant, and that this dose be maintained throughout pregnancy (Grade C recommendation).

Recommendation: in patients with obstetric APS it is recommended that low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) be added to acetylsalicylic acid as a secondary prophylactic treatment at the moment pregnancy is confirmed, and this should be maintained throughout the pregnancy. The dose of heparin should be individualised depending on the risk level of each patient (Grade C recommendation).

Only a small percentage of patients with obstetric APS have a good prognosis for pregnancy if they do not take appropriate prophylactic medical treatment during gestation.1 Complications in pregnancy include repeated abortions, foetal death, preeclampsia and premature birth, among others. These are caused by several mechanisms, including placental dysfunction and placental thrombosis and infarct. Due to this the treatment of APS during pregnancy has traditionally been based on attenuating the prothrombotic state of these patients.

Different preventive treatments have been used in recent years. These include ASA, unfractionated heparin, LMWH, prednisone and other glucocorticoids and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), as the sole treatment or combined, with the intention of improving the gestational prognosis. It is therefore relevant to evaluate the efficacy of these drugs to see which treatment is the best for administration to these patients.

Treatment prior to conceptionVery few studies evaluate the need for prophylactic treatment before conception. A randomised clinical trial2 evaluated enoxaparin (41mg) and ASA (81mg) vs. a placebo in patients with APS who had previously suffered abortions, and it found that the combination of enoxaparin and ASA used prophylactically did not statistically improve the rate of live births; however, it did improve the rate of pregnancy from 0 to 6 months, and it reduced the rate of spontaneous abortions (LoE 1+). On the other hand, a series of cases evaluated 21 expectant mothers with primary APS who received low doses of ASA prior to conception. In previous pregnancies without treatment the rate of live births amounted to 6.1% (46 previous foetal losses and 3 live births), while after the treatment before conception the rate of live births amounted to 90.5% (21 pregnancies with 19 live births)3 (LoE 3).

Treatment during pregnancy10 studies were identified which evaluate treatment during pregnancy and the use of ASA and heparin in patients with obstetric APS. Two systematic reviews4,5 showed that the combination of ASA and heparin may reduce the loss of pregnancies in women with antiphospholipid antibodies (APA) (LoE 1+). Another systematic review and meta-analysis6 proposed that the combination of unfractionated heparin (5000–10,000units every 12h) and ASA (81mg), given before conception and compared with a monotherapy of ASA, was significantly more beneficial in terms of the live birth rate. Nevertheless, there are very few studies and what is more those which evaluate the combination of LMWH and ASA as treatment during gestation offer lower quality evidence. This combination has not yet been shown to have a clear benefit in improving the rate of live births (LoE 1−). Finally, the last systematic review7 evaluated the repeat abortion rate in patients with thrombophilia as well as in patients with APS, and it found no significant results for the combination of LMWH+ASA vs. ASA alone or a placebo in both groups. However, for the patients with APS unfractionated heparin associated with ASA was the best treatment in reducing foetal losses (LoE 1+).

A randomised clinical trial8 showed that preventive treatment with LMWH and ASA gave a higher percentage of births than IVIG in the treatment of women with APS who had suffered repeated abortions (LoE 1+). Another randomised clinical trial9 compared 2 different doses of enoxaparin (20mg vs. 40mg) and ASA, without showing any differences between the groups (LoE 1−). The third trial10 compared LMWH and ASA with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), showing that the treatment with LMWH gave a better rate of live births (LoE 1−). The fourth of these trials11 compared dalteparin and ASA vs. ASA as monotherapy, and it found no differences in hypertension disorders between the groups (LoE 1−).

Finally, a cohort study12 showed that the combination of LMWH and ASA is better than ASA alone in preventing abortions, while a second cohort study13 found no differences between the use of ASA alone or combined with LMWH in preventing maternal and foetal complications such as hypertension during pregnancy, prematurity, delayed intrauterine growth or neonatal death (LoE 2+). Other studies were also identified which evaluate the use of other preventive treatments, especially IVIG or glucocorticoids. The results of different studies on the use of IVIG in APS are controversial. One cohort study14 found no differences in terms of the prognosis for pregnancy between adding IVIG to the conventional treatment with ASA and LMWH (LoE 2+). On the other hand, another cohort study15 showed that the use of IVIG is better than the use of prednisone and ASA in pregnant women with obstetric APS to prevent the development of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia, but not to improve the foetal prognosis (LoE 2−).

In the light of all of these results, and in spite of the lack of studies and the low quality of ht evidence found, the work group considers it to be appropriate to recommend the combination of LMWH and ASA at prophylactic doses in all patients with obstetric APS. The administration of ASA should start before conception because of its possible benefit and the low risk of this prophylactic action, while LMWH administration should start as soon as pregnancy is confirmed. ASA and LMWH should be maintained throughout gestation. Although some studies do not agree, the combined use of LMWH and ASA at low doses, as well as increasing the rate of live births, may also prevent other complications during pregnancy in patients with obstetric APS: its effect is superior to the use of treatment with ASA as a monotherapy. Nevertheless, the group of panellists recognises that the dose of LMWH should be individualised depending on the risk of each patient.

Refractory obstetric antiphospholipid syndromeIn patients with obstetric APS who suffer a new obstetric complication in spite of conventional treatment, what should the therapeutic attitude be?

Recommendation: in refractory obstetric APS it is recommended to add starting hydrochloroquine before pregnancy to the conventional treatment and maintain this throughout gestation, alone or in combination with prednisone or equivalent until the start of pregnancy (≤10mg/day during the first quarter) (Grade D recommendation).

Recommendation: in patients who develop complications associated with placental insufficiency (preeclampsia or delayed intrauterine growth) in spite of conventional treatment, it is recommended that pravastatin be added (20mg/day) from the start of the complication (Grade C recommendation).

Recommendation: the use of IVIG and plasmapheresis is not recommended from the first, although this may be considered in the absence of a response to other treatments (Grade √ recommendation).

The conventional treatment of obstetric APS is the combination of aspirin at an antiaggregant dose and LMWH at a prophylactic dose.5 However, from 20% to 30% of these patients do not achieve the final objective of a live birth.16 The main risk factors associated with failure of conventional treatment are associated with the previous obstetric history and the antibody profile, especially triple positivity for APA.17–19 The identification of these risk factors and better knowledge of the mechanisms of action of LMWH and the use of new drugs have made it possible to design new therapeutic strategies for refractory obstetric APS.20

As well as its antithrombotic effect heparin has a broad range of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating properties.21 The current attitude of the majority of experts is to use aspirin and heparin at prophylactic doses during the whole pregnancy. When heparin starts to be administered may be decisive for its efficacy, and it should be administered in the first stages of gestation. In patients with obstetric APS it has been observed that better results are obtained by gradually adjusting the prophylactic dose of heparin for patient weight throughout pregnancy better results are obtained compared with maintaining a single dose.22 Nevertheless, in refractory obstetric APS, the results of studies that evaluated the modification of the dose of heparin during pregnancy have not been conclusive.23,24

Hydrochloroquine (HCQ) is commonly used in autoimmune diseases, especially in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), where it is recommended during pregnancy.25 Although there is little information on obstetric APS and what there is consists of retrospective studies, its anti-inflammatory, immunoregulating and antiaggregant properties make HCQ a good therapeutic option.26 Moreover, in vitro as well as in several animal models HCQ is able to correct several of the biological functions which are altered by APA.27–30 Several retrospective studies show the efficacy of HCQ in combination with conventional therapy, in patients with obstetric APS as well as in those with refractory obstetric APS.18,26,31–36 A recent retrospective study has therefore shown that use of HCQ at a dose of 400mg, especially when commenced prior to conception, is useful in patients with refractory APS who have suffered no previous thrombotic episodes.36

The glucocorticoids inhibit the complement pathway and reduce the number of NK cells, so that it has been suggested to have a possible beneficial effect in patients with recurrent abortions. In an open study with a limited number of patients, prednisone at a dose of 10mg/day during the first three months of pregnancy significantly increased the rate of live births without increasing side effects in patients with refractory obstetric APS.37 In a recent retrospective multicentre study18 that included 49 patients with refractory obstetric APS, the combination of glucocorticoids or HCQ with conventional treatment was also associated with a significant increase in the number of life births. The beneficial effect of treatment with glucocorticoids was maintained in the multivariable analysis.18

IVIG have been used in obstetric APS with contradictory results. Some studies find no significant differences between patients treated solely with IVIG or in combination with conventional treatment when they are compared with those who only receive the latter.10,38 Other authors have mentioned positive results.39 In spite of the heterogeneous results, IVIG will be reserved for use with selected cases of patients with refractory obstetric APS. At the current time there is no agreement on the duration, frequency or optimum dose of IVIG.40

In cases of obstetric APS with high risk factors such as previous thrombosis, severe complications during pregnancy and lack of response to conventional treatment, together with triple APA positivity, different apheresis procedures have been used, such as plasmapheresis or immunoadsorption.41,42 In a recent study25 14 pregnant patients with high risk APS received conventional treatment with added weekly apheresis and IVIG, giving a 94% success rate. These preliminary results were confirmed recently by a retrospective study that included a higher number of patients with refractory obstetric APS.36

APS is one of the main risk factors for the development of preeclampsia which is, in turn, one of the main maternal complications during pregnancy. On the other hand, prematurity and delayed intrauterine growth are the 2 main foetal complications.43 A recent open prospective study44 described the beneficial effect of associating a 20mg/day dose of pravastatin with conventional treatment in patients with APS who developed preeclampsia or delayed intrauterine growth. In this study association with pravastatin from the start of the said complications improved the figures of arterial blood pressure, increased placental flow and, most importantly, obtained a 100% rate of live births.

PostpartumHow long should thrombotic prophylaxis last postpartum in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome?

Recommendation: in previously anticoagulated patients with thrombotic APS vitamin K antagonists should be reintroduced immediately postpartum (Grade √ recommendation).

Recommendation: in women with obstetric APS thromboprophylaxis is recommended after birth with low molecular weight heparin at a prophylactic dose during at least 6 weeks (Grade √ recommendation).

Recommendation: in patients with thrombotic APS who for some reason are not receiving long-term anticoagulation, thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin is recommended at intermediate doses and individualising depending on risk, during at least 6–12 weeks after birth (Grade D recommendation).

Although experts have made different recommendations for the prevention of obstetric complications, there is no agreement. In the general population venous thromboembolic disease occurs in 0.5–2.2 per 1000 pregnancies (a risk 15–35 times greater than it is in women who are not pregnant) and it may appear during gestation or the puerperium. Although the absolute number is low, it is still one of the first causes of morbimortality during pregnancy and the puerperium. During the postpartum period the risk of thrombosis is higher in the first 3–6 weeks, although it may persist until week 12.45,46

There is very little evidence on this point. The recommendations published in clinical practice guides on the presence of acquired thrombophilia and APA are inconsistent, as they are based on observational studies and on extrapolation from studies of non-pregnant women. A systematic review by Bain et al. also concluded that they found no sufficiently high quality studies to establish recommendation on the postnatal management of thromboembolic disease.45–51

Taking this lack of evidence into account, different scientific societies and groups of experts have made the following recommendations47–50:

- •

In women with APS (APA+previous venous thromboembolism and not receiving indefinite anticoagulation) 6 weeks at intermediate or high doses of LMWH are recommended, or switching to a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) (The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, ACOG; Societat Catalana d’Obstetrícia i Ginecologia, SCOG; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, RCOG and the American College of Clinical Pharmacy, ACCP).

- •

In women with thrombotic APS who have previously been anticoagulated, the recommendation is to switch to a therapeutic dose of LMWH during pregnancy and, after birth, to recommence VKA as soon as possible (ACOG, SOGC, RCOG and ACCP).

- •

Regarding post-Caesarean prevention, they recommend thromboprophylaxis during at least 6 weeks if there is a history of thrombosis, preeclampsia with delayed intrauterine growth, comorbidities such as SLE or known thrombophilia (ACCP).

- •

As the results of the different studies which were identified are not consistent, the efficacy of the intervention has not been proven by randomised clinical trials, so that it is based on expert recommendations, and in the majority of scenarios they prefer to use thromboprophylaxis during at least 6 weeks.

- •

Although this subject is controversial, given its clinical importance and in spite of the fact that there are no good quality clinical trials or studies, all of the guides recommend thromboprophylaxis.52–54 Additionally, the opinion of the patient must always be taken into account. The group of panellists considers that, given the high thrombotic risk of women with thrombotic APS or obstetric APS during the puerperium, thromboprophylaxis at a prophylactic or intermediate dose should be administered from 6 to 12 during the postpartum period (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3.Intermediate doses of low molecular weight heparin.

Drug Dosea Bemiparin (Hibor©) 5000U/d sc (75UI/d sc approx.) Enoxaparin (Clexane©) 1mg/kg/day Tinzaparin (Innohep©) 8000UI/d sc

What should the therapeutic attitude be for women with antiphospholipid syndrome during assisted reproduction techniques?

Recommendation: in patients with APS who are going to perform assisted reproduction techniques it is recommended that risk be individualised by associating prophylactic or therapeutic doses of LMWH as the anticoagulant (Grade D recommendation).

Recommendation: patients with APS and oral anticoagulation will switch to low molecular weight heparin at a therapeutic dose before ovary stimulation, and they will continue to take it throughout pregnancy (Grade D recommendation).

Recommendation: the recommendation for patients with APS who are not taking chronic anticoagulation is treatment with an antiaggregant dose of acetylsalicylic acid and low molecular weight heparin at an individualised dose from the start of ovary stimulation, maintaining this treatment throughout gestation (Grade D recommendation).

Recommendation: in women with antiphospholipid antibodies and triple positivity or high levels of APA, due to the risk of thrombosis as well as the appearance of obstetric complications it is recommended to use low molecular weight heparin plus acetylsalicylic acid (Grade D recommendation).

Recommendation: the recommendation is to avoid ovary hyperstimulation syndrome, which is a risk factor for secondary thrombosis during assisted reproduction techniques, by using low risk hormonal protocols for this complication (Grade D recommendation).

The increase in the concentrations of oestrogens in serum during ovary stimulation or the induction of ovulation when using ART leads to changes in coagulation that induce a state of hypercoagulability. Due to these changes the risk of thrombosis during ART increases slightly in the general population, although the risk is higher in patients with congenital or acquired thrombophilia.55 There is scientific evidence for the safety and efficacy of ART in patients with APS, on condition that suitable antithrombotic treatment is administered.56–60 Although it is complicated to set fixed recommendations for the most suitable antithrombotic treatment during ART in patients with APS, current scientific evidence makes it possible to establish antithrombotic recommendations which must be individualised.

There are too few studies to make it possible to know the prevalence of thrombosis with a high methodological quality. This is also the case for the importance of preventive treatment for thrombosis during ART in patients with APS or who are carriers of APA.56 The only finding here consisted of some series of cases57–60 (LoE 3). Current recommendations are based on the results of these studies and the recommendations in the clinical practice guides published by different scientific societies26,49,61 (LoE 3 and 4). Thus in general the advice is to offer the same treatment as is given to pregnant patients, as prophylaxis for thrombosis and obstetric complications26,49,61–63 (LoE 3 and 4). Nor are the duration and dose of thromboprophylaxis during and after ART well known, although they are similar to those used after other surgical procedures with a low risk of bleeding64,65 (LoE 4). Regarding anticoagulant treatment during follicular puncture, the experts conclude that LMWH should be suspended during at least 12h before performing this procedure, restarting administration 6–12h after puncture, to reduce the risk of bleeding56–60 (LoE 4).

As the different clinical practice guides published recently all agree and recommend the same thromboprophylactic treatment, the preparatory group for this document recognises that these recommendations are directly applicable to our health system and may be extrapolated to all ART. Thus although there is little scientific evidence, and in spite of the risk of haemorrhage, antithrombotic treatment is recommended for patients with APS or who are APA carriers who are going to undergo ART. Nevertheless, it is not recommended that APA be determined for all of the patients who are going to undergo ART.56

After pregnancy and the puerperiumIn patients with obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome without thrombotic manifestations, should they be monitored outside the period of pregnancy?

Recommendation: in patients with isolated obstetric APS monitoring is recommended after pregnancy and the puerperium, as they have a higher risk of thrombosis than the general population (Grade C recommendation).

Recommendation: in the said monitoring it is recommended that cardiovascular risk be individualised (identifying the presence of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, smoking and dyslipidemia, etc.) and informing about, eliminating or controlling existing cardiovascular risk factors (Grade B recommendation).

Recommendation: during monitoring it is prudent to individualise advice on the use of acetylsalicylic acid at low doses as a primary antithrombotic prophylaxis. There is no conclusive proof that this should only be administered to patients with the highest thrombotic risk (those who are positive for lupus anticoagulant or patients with triple antibody positivity) (Grade B recommendation).

Recommendation: the use of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin is recommended in situations with a high risk of venous thrombosis (Grade √ recommendation).

There is clear scientific evidence on what should be done in the case of patients with thrombotic APS (thrombosis as the sole manifestation of APS or accompanied by a history of obstetric complications). However, there are still few studies which evaluate what should be done over the long-term in patients with purely obstetric APS but without a history of previous thrombosis. It is necessary to know the thrombotic risk of these patients and evaluate and individualise the use of antithrombotic prophylaxis.

Different prospective and retrospective cohort studies and series of cases43,66–71 show an increase in thrombotic risk during the long-term follow-up of patients with a history of obstetric APS without previous thrombosis (LoE 4). The majority of these studies either fail to supply sufficient data on the use of low-dose ASA or prescribe this treatment for all of their patients, so they do not help to elucidate the protective role of this as a primary antithrombotic prophylaxis. There are 2 retrospective case–control studies54,72 that include patients with APS and repeated abortions or gestational losses, and these too show an increased thrombotic risk in this subgroup of patients with obstetric APS (LoE 3b). All of the studies conclude that it is necessary to perform follow-up and inform these patients about thrombotic risk and the importance of controlling associated cardiovascular risk factors.

The primary long-term prevention of thrombosis by using low-dose ASA in all patients with isolated obstetric APS is controversial. There are no randomised studies that would show the benefit of treatment using low-dose ASA in all such patients, and nor are there any studies that classify and individualise thrombotic risk in these patients. The current recommendation for treatment is based on the results of a recent meta-analysis that evaluated APA carrier patients without previous thrombosis, sub-analysing the group of patients with isolated obstetric APS.73 This study showed a protective effect of low-dose ASA in patients with isolated obstetric APS, in asymptomatic patients who are APA carriers and in patients with SLE (LoE 3). As a result, the authors conclude that during follow-up patients should be advised to use low-dose ASA as a primary antithrombotic prophylaxis if they have isolated obstetric APS. Nevertheless, individualised analysis of these patients depending on their cardiovascular risk, APA positivity profile and treatment with HCQ, published at a later date by the same group, found no protective effect in patients with isolated obstetric APS74 (LoE 3). According to the authors this lack of a relationship was probably due to the limited number of patients with isolated obstetric APS in this last meta-analysis. Because of all these reasons, and due to the risk of haemorrhage during treatment with low-dose ASA, the benefit of administering low-dose ASA to all obstetric APS patients without a history of thrombosis is not clear. The conclusion is that it should be administered to selected high-risk patients, as is the case for healthy carriers of APA and, during follow-up, to individualise the thrombotic risk and detect and treat associated cardiovascular risk factors in these patients and inform them about their risk of thrombosis, as well as using prophylactic LMWH in situations at high risk of thrombosis75–78 (LoE 4).

The results of the different studies which were identified are consistent, as all of them describe an increased thrombotic risk in this population subgroup and emphasise the need to grade thrombotic risk (according to their antibody profile, associated cardiovascular risk factors or the presence of other autoimmune diseases) while detecting and controlling cardiovascular risk factors. All of these studies indicate the need to administer low-dose ASA in selected patients with greater thrombotic risk, while they do not make a clear case for the benefit of administering the said treatment to all patients without individualising their risk.

Given that there are a noteworthy number of patients with isolated obstetric APS, and because the different studies, in spite of their limitations, show an increased risk of thrombosis in this population subgroup, the preparatory group considers that these patients should be monitored and assessed. Monitoring, controlling cardiovascular risk factors and the primary prevention of thrombosis using low-dose ASA, at least in the patient subgroup with high thrombotic risk, have a clear benefit in comparison with not applying any of these interventions.

Special situationsSolid organ transplantIn patients with antiphospholipid syndrome who require a solid organ transplant, what should the therapeutic attitude be?

Recommendation: rigorous anticoagulation control is recommended before and after a solid organ transplant, especially a kidney transplant (Grade √ recommendation).

Recommendation: routine screening for antiphospholipid antibodies before a solid organ transplant in all patients with a history of thromboembolic events (Grade √ recommendation).

The origin of thrombosis in patients who require a solid organ transplant is multifactorial regardless of the location of the transplant. The surgery itself, the disease which gave rise to the need for transplant and the prolonged immobilisation which both situations involve are risk factors for thrombosis. Most especially, terminal kidney failure, dialysis and permanent vascular access are risk factors for thrombosis. This is always so for kidney transplant, but it is also the case in the transplant of other solid organs. Moreover, patients with APS or APA who require transplant have the additional risk of losing the graft due to systemic thrombosis, graft thrombosis or thrombosis of the vascular anastomosis.79–84 The risk is higher in patients with APS and kidney transplant,85–95 although there are no meta-analyses or studies with controls. Four retrospective studies of a total of 2918 kidney transplants agree that the detection of APA at the moment of transplant is associated with a greater number of complications and more losses of the graft in patients with SLE as well as in patients with other diseases.86,87,90,92 In a retrospective study of 178 kidney transplants without SLE, Ducloux et al.87 found post-transplant venous thrombosis in 18% of the patients with APA and in 6.2% of the patients without the said antibodies, respectively (P<.001). Post-transplant arterial thrombosis is also more common in patients with APA (8 vs. 2.3%, respectively; P<.001). In 85 patients with SLE, Stone et al.92 found manifestations of APS in 15 of 25 kidney transplant patients with APA and in 5 of 60 kidney transplants without these antibodies (P<.0001).

Four prospective studies of a total of 2215 kidney transplants found more complications in patients with APS or APA.88,89,94,95 The data are contradictory respecting the evolution of transplanted kidneys. Wagenknecht et al.95 find more APA in the group with loss of graft than they do in the group with a functioning transplant (57% vs. 35%; P=.02). Forman et al.89 do no link anticardiolipin antibodies with graft loss. Fernandez-Fresnedo et al.,88 in a prospective study of 197 kidney transplants, do not associate the detection of APA prior to transplant (27%) with a higher risk of post-transplant complications. Nevertheless, 15.7% of the patients with APA de novo after transplant did show a significant rise in graft rejection.

Nor are there any meta-analyses or studies with controls in the case of liver and heart transplants which evaluate the risk of complications in patients with APS or APA. A retrospective study of 35 liver transplant patients83 finds anticardiolipin antibodies in all 7 patients with hepatic artery thrombosis and in 15 of the 28 transplants without thrombosis (53.5%), although other studies do not confirm these findings. Two prospective studies that include 45 pacientes96,97 and 2 retrospective studies with 299 patients98,99 did not find increased risk of thrombosis after liver transplant.

In spite of the risk of bleeding,100,101 the experts agree in recommending rigorous control of anticoagulation before and after transplant.94,100 Although it is true that the preference is to use LMWH or unfractionated heparin due to its shorter half life,102 the results are similar with oral anticoagulants.93

Lastly, given the increased risk of thrombosis and that sudden thrombosis intra- or post-transplant may be the first sign of catastrophic or undiagnosed APS,81,103 some experts recommend the routine screening of all patients prior to kidney transplant.91 Others only recommend this in patients with a history of arterial or venous thrombosis.86,101

Antiphospholipid antibodies and neoplasiasIn patients with antiphospholipid antibodies and neoplasias, what should the therapeutic attitude be?

Recommendation: thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin is recommended in patients with a high risk serological profile and neoplasias, especially in situations that increase thromboembolic risk (surgery, catheter implant, the start of chemotherapy) (Grade √ recommendation).

Patients with solid or haematological tumours have a higher prevalence of APA than the controls.104,105 Evaluation of whether there is a higher incidence of thromboembolic manifestations in these patients gives contradictory results. Some studies find an increase of thrombosis in patients with APA106 while others do not find this association.107,108

The highest incidence of thrombosis has been described in solid tumours and in association with APA isotypes IgG or IgA109,110 and antibodies against domain I of aβ2GPI.111 Although the presence of APA may contribute to increased risk of thrombosis in patients with malignity,112 it does not seem clear that APA levels contribute to the mechanism causing thrombosis in these patients. On the contrary, although certain neoplasias such as haematological or lymphoproliferative ones may affect the production of APA, as IgM isotypes predominate there is no greater risk of thrombosis.108 Levels of APA are also known to possibly fall and even to disappear after the commencement of chemotherapy.113 Thus the experts agree that thromboprophylaxis with LMWH is important for these patients, above all in situations of thromboembolic risk (prolonged immobilisation, surgery or catheter implant). Some studies conclude that commencing certain chemotherapy treatments increases the risk of causing thrombosis.114,115 Based on this, the experts understand that it would be recommendable to use primary thromboprophylaxis, and that in the patients where APA levels have fallen or disappeared anticoagulation could be replaced by antiaggregation.

Following up healthy individuals with APA showed an increase in the incidence of lymphoproliferative tumours, and more specifically non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, in comparison with the general population. The authors concluded that the presence of APA may be a risk factor for haematological neoplasias, and that this should be taken into account in the initial evaluation of older patients, those with high titres of APA and the presence of thrombosis with no known cause.116 Other studies find haematological neoplasias in 26% of patients with APA,113 with a risk 2.6 times higher of suffering this type of neoplasia.117 Neoplasia is also one of the main causes of death in these patients.43 A retrospective study compared patients with a solid neoplasia and APA with or without thromboembolic manifestations with a control group. They found 8% of APA in the patients with thrombosis vs. 1.4% in those without thrombosis; only 4 patients remained APA positive; in the patients with thrombosis and APA there were no differences in their demographic characteristics, clinical pattern or the prognosis when they were compared with the patients with thrombosis and without APA. Given these results and together with the low titre and transitory nature of the APA, the authors concluded that APA plays no pathogenic role in thrombosis in patients with solid cancer and thrombosis.118

Temporary suspension of anticoagulationIf it is necessary to temporarily suspend anticoagulation in patients with the antiphospholipid syndrome, what should be the therapeutic attitude?

Recommendation: the recommendation is to suspend anticoagulation in the case of invasive procedures with moderate or high risk of haemorrhage, and to perform bridging therapy (Grade D recommendation).

Recommendation: for bridging therapy the recommendation is to use individualised doses of low molecular weight heparin adjusted for weight and kidney function, suspending it at least 24h prior to the invasive procedure (Grade D recommendation).

Recommendation: In pregnant patients with APS who use low molecular weight heparin at therapeutic or intermediate doses, the recommendation is to suspend this at least 24h before birth or other procedures. During birth it is not necessary to suspend treatment in patients who use acetylsalicylic acid at a dose of 100mg (Grade D recommendation).

There is little evidence regarding how to suspend anticoagulation in patients with APS or the presence of APA. Taking into account that 10% of anticoagulated patients (with or without APS) will receive surgery in one year, the perioperative management of these patients, who may be at high risk of thrombosis, is vitally important.119

The BRIDGE study, which only included anticoagulated patients with arrhythmia, found no significant differences in thrombotic risk between patients who had received bridging therapy and those who had not. Nevertheless, an increase in the risk of haemorrhage was detected compared with the patients who had not received bridging therapy in terms of total bleeding (13.1% vs. 3.4%), as well as major bleeding (4.2% vs. 0.9%).119 Different meta-analyses have shown similar findings.120,121

Other clinical trials included highly heterogeneous patients or insufficient sample sizes of patients with APS,120–122 hindering the establishment of recommendations. Thus the recommendations found in the literature are chiefly based on ACCP guides (2012), which distinguish depending on the thrombotic risk of the patient and the risk of haemorrhage during surgery or the procedure.119,123

Subsequently, extrapolating from BRIDGE study data, groups of experts have drawn up new recommendations for patients at low or intermediate risk of thrombosis, such as the presence of acquired thrombophilia.124 These recommendations conclude: (1) in patients with APS (high thrombotic risk or recent venous thrombosis <3 months) 2 situations may arise: (a) if the risk of haemorrhage is moderate or high, VKA must be suspended at least 3 or 4 days beforehand, starting with heparin at intermediate doses and recommencing anticoagulation as soon as possible with intermediate or therapeutic doses of LMWH if the patient is not at risk of bleeding; (b) if there is a low risk of haemorrhage, VKA should not be suspended. (2) If the patient has an intermediate risk of thrombosis (such as the presence of APA or venous thrombosis in the previous 3 months), if the risk of haemorrhage is moderate or high, VKA should be suspended at least 3 or 4 days beforehand, starting with LMWH at a prophylactic dose and maintaining this until it is possible to restart VKA, overlapping both treatments during at least 4 days; if the risk of haemorrhage is low, the recommendation is not to suspend VKA.

Respecting direct action oral anticoagulants (DOAC), the recommendations are based on international records or pivotal studies. In general the experts do not recommend using LMWH after suspending direct action oral anticoagulation for at least 72h, 48h or 24h before the procedure (basing the decision to suspend it earlier on the renal function of the patient). If the duration of the postoperative state or the situation of the patient makes it impossible to recommence treatment with the said anticoagulant, the recommendation is to commence with LMWH at a prophylactic dose and maintain this, depending on patient evolution.124,125

For pregnant women with obstetric APS international groups of experts recommend using LMWH at therapeutic or intermediate doses, suspending the treatment at least 24h prior to the procedure. If they are taking ASA, the therapy may be maintained and LMWH will recommence at a suitable dose in less than 24–48h.123

The group of panellists considers that the results of the BRIDGE trial and the meta-analyses are consistent respecting the high risk of haemorrhage in bridging therapy in general, and that in low-risk cases the recommendation is not to use LMWH; however, there is little evidence for patients at high risk of thrombosis, such as patients with APS. Due to this, the group of panellists has taken into account the recommendations of other groups of experts and has decided to recommend, in patients with APS, a bridging therapy that balances the benefit/risk of thrombosis, while minimising the risk of bleeding due to surgery.

Moreover, as there is a high risk of recurrence while anticoagulation is suspended in many patients with APS, the group of panellists considers that in these patients the risk of haemorrhage due to surgery should be evaluated, establishing bridging therapies which are adapted to the risk in a personalised way.

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndromeIn a patient with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome, what should the therapeutic attitude be?

Recommendation: in a patient with catastrophic APS the initial treatment should include what is known as triple therapy, which consists of anticoagulation, preferably with intravenous unfractionated heparin, associated with high doses of glucocorticoid, plasmapheresis or intravenous immunoglobulin (Grade D recommendation).

Recommendation: in cases that are refractory to triple therapy associating rituximab or eculizumab may be considered (Grade D recommendation).

As the prevalence of catastrophic APS is very low (<1% of all APS cases), all of the most relevant available information about this rare but severe situation originates in the data of the international registry of catastrophic APS which, according to updated figures, contains the information corresponding to approximately 500 patients.126

Although the mortality of catastrophic APS has fallen in recent years, it is still very high (it currently stands at 63%).127 The improvement in the prognosis for catastrophic APS may be due to factors such as earlier identification, the correction and treatment of causal factors (such as infection) and, as a result of all of these factors, earlier commencement of the treatment.128

Diagnosis of catastrophic APS is based on classification criteria that were updated in 2005129 (see Table 2 in part I). As it is a rare entity the experts agree in suspecting catastrophic APS above all in patients where thrombosis rapidly appears in several organs, together with the presence of APA. Studies emphasise that ruling out other diseases is of key importance in differential diagnosis. These fundamentally affect microcirculation, and they include microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia or thrombotic thrombopenic purpura130 as well as eclampsia, preeclampsia or the HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count) in pregnant patients.131 Lastly, and due to the fact that in 2/3 of patients with catastrophic APS there is a precipitating factor, the importance of identifying these factors is emphasised, as if they are treated or corrected this may improve the evolution of catastrophic APS.127 These factors most especially include infections (47%), cancer (18%), surgery (17%), subtherapeutic anticoagulation (11%), oral contraceptives (7%) and pregnancy.129,131

The evidence found on the treatment of catastrophic APS is restricted to studies of series of cases and expert consensus.

Anticoagulation is considered to be the fundamental treatment for catastrophic APS. The evidence for this originates in the analysis of 280 patients with catastrophic APS, of which 244 received some type of anticoagulation vs. 36 patients who did not. Survival was significantly better in the anticoagulated patients (63% vs. 22%; P<.0001).129 Although there are no studies which determine the specific type of anticoagulation, the authors conclude that unfractionated heparin should be used, above all because its effect is reversible and the preference for intravenous administration in the most critical patients.128

There are no prospective studies or any clearly significant data on the use of glucocorticoids in catastrophic APS. The majority of experts recommend using them to reduce the extremely intense inflammatory response which occurs in catastrophic APS.128 In the majority of the cases described in the literature a combination of anticoagulation and glucocorticoids was used.126,128 No significant differences were found when the impact of glucocorticoids on the prognosis for catastrophic APS was analysed specifically.132 Nevertheless, a large number of the patients included in the international register of catastrophic APS and in the published isolated cases were treated using this combination. The groups of experts therefore recommend always using high intravenous bolus doses of glucocorticoids (500–1000mg/iv/3 days)together with anticoagulation, followed by oral glucocorticoids (1mg/kg).128 In the case of associated severe infection the use of more moderate doses of glucocorticoids should be considered.

Due to the beneficial role of plasmapheresis in patients with different types of thrombotic microangiopathy, as well as the accepted pathogenic mechanism of the APA,133 it has also been proposed as a potential treatment in combination with anticoagulation and glucocorticoids in patients with catastrophic APS.134 A study in which 18 patients were treated using triple therapy and 19 patients were only treated with anticoagulation and glucocorticoids, showed a higher survival rate (77.8% vs. 55.4%; P=.083) in those who received triple therapy.135

In connection with IVIG associated with anticoagulation and glucocorticoids, the studies show that the patients who received this combination had a higher survival rate than those who did not.128 However, in the majority of patients IVIG was used together with plasmapheresis, and this combination too showed a higher survival rate. Although there is no definitive standardised dose,131 0.4g/kg is used during 5 days.128 Some authors recommend administering IVIG after plasmapheresis; nevertheless, other experts administer it simultaneously with plasmapheresis, supplementing it the next day with 200mg/kg to compensate for the immunoglobulin that may have been withdrawn during plasmapheresis.

The last analysis of the international catastrophic APS registry (the CAPS registry)136 evaluated the relationship between triple therapy and mortality in these patients. The triple therapy was associated with greater survival in comparison with the group that had not received the same treatment (adjusted OR 7.7; CI 95%: 2.0–29.7) or other combinations of treatments included in triple therapy (adjusted OR 6.8; CI 95%: 1.7–26.9). Triple therapy gave rise to a reduction of 47.1% in mortality compared with the group that did not receive it, and a reduction of 34.4% in comparison with any other combination of treatments. The authors concluded that triple therapy is independently associated with a higher rate of survival in patients with catastrophic APS.136 The expert therapeutic attitude to catastrophic APS is therefore to use triple therapy: anticoagulation, glucocorticoids and plasma replacement or IVIG.

The review of the international catastrophic APS registry137 analysed patients who been treated using rituximab. 20 patients in treatment with rituximab were identified, and in 8 of them it was the first line of treatment, while in the others rituximab was administered as rescue therapy. 15 of the 20 patients were said to have a suitable response to rituximab.

Eculizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody which inhibits the activation of fraction 5 of the complement. It is indicated in atypical uraemic-haemolytic syndrome and in the nocturnal paroxistic haemoglobinuria.138 As activation of the complement has been considered to be a key factor in animals models of APS,139 eculizumab has been used in severe isolated cases of catastrophic APS.140 Taking into account the fact that eculizumab has only been used in a very small number of patients with catastrophic APS, and until well-designed clinical trials appear, the authors conclude that eculizumab may be used in case of catastrophic APS that is refractory to triple therapy.139,140

Some authors recommend using cyclophosphamide in cases of catastrophic APS associated with SLE. A study compared the demographic and clinical characteristics and analytical results of 103 patients with SLE and catastrophic APS with those of 127 patients who only had primary catastrophic APS.141 In 47% of the SLE-APS patients who were given cyclophosphamide mortality fell significantly (odds ratio=0.20; 0.006–0.71; P=.013). The patients with catastrophic APS without associated SLE showed an increase in mortality (odds ratio=8.5; 1.91–37.83), although these patients were more severe and had a larger number of affected organs.

ConclusionsThis is the first official consensus of the SER for the diagnosis and treatment of primary APS. Following an exhaustive review of the scientific evidence, and as there are few high quality studies, the recommendations are fundamentally based on systematic reviews, cohort studies and case and control studies, together with expert opinions.

25 recommendations were drawn up for the areas of treating obstetric APS and special situations, such as catastrophic APS. Treatment algorithms were prepared on the basis of the recommendations, and these shown the approach to treating APS in summarised form (Figs. 1 and 2).

To treat obstetric APS, and based on current scientific evidence, prior to conception it is recommended that antiaggregant doses of ASA be taken, with LMWH from the start of pregnancy. This treatment will be maintained throughout gestation. Heparin should be continued after birth during from 6 to 12 weeks, depending on the thrombotic risk of each patient. In the cases when new obstetric complications emerge in spite of the standard treatment, the panel of experts recommends adding HQC, alone or in combination with low doses of prednisone. In patients who develop severe pre-eclampsia or CIR in spite of the standard treatment, adding pravastatin to the conventional treatment may be considered (at a dose of 20mg). The use of IVIG and plasmapheresis in obstetric APS is still a highly controversial therapeutic option. However, the panel of experts considers this to be a final option if there is no response to other treatments.

In patients with obstetric APS without thrombosis, there is higher risk of thrombotic event after pregnancy than is the case in the general population, so that the panel of experts recommends monitoring and correct cardiovascular risk factors. For patients who are considered to be at higher risk of thrombosis, adding prophylaxis with antiaggregant doses of ASA should be considered.

A new aspect of these recommendations is that the existing evidence on the therapeutic attitude during ART for women with APS has been reviewed. There are too few good quality studies of this question to permit establishing therapeutic norms in this situation. Based on a series of cases and the recommendations in clinical practice guides, the panel of experts recommends preventing ovary hyperstimulation syndrome by using hormonal protocols with low risk for this complication. During the assisted reproduction technique it also recommends the same individualised prophylaxis against thrombosis and obstetric complications (low dose ASA associated with prophylactic or therapeutic doses of LMWH) as it does for pregnant women with APS.

Finally, the panel of experts made recommendations for what it denominated special situations. In patients with APS who need a solid organ transplant rigorous control is recommended of anticoagulation before and after transplant, above all kidney transplants. In situations when invasive procedures with a moderate to high risk of bleeding are due to be carried out, the recommendation is to suspend anticoagulation and maintain rigorous control of the bridging therapy with heparin. Lastly, in catastrophic APS, which is an especially severe clinical situation, the panel of experts, based fundamentally on the results of the catastrophic APS patient registry, recommends commencing what is known as triple therapy together with early identification of the condition and the correction of its causal factors. Triple therapy consists of unfractionated heparin at a therapeutic dose, in combination with corticoids, plasmapheresis and IVIG.

After the exhaustive review of the diagnosis and treatment of APS, it is clear that there is a need for well-designed multicentre trials that classify patients not only according to the different clinical manifestations, but also according to the serological profile and the presence of comorbidities. These would make it possible to determine which therapeutic option is the best for each clinical situation. More studies are also needed to supply deeper knowledge about the pathogenesis o the disease, as well as new studies to clarify the role of the APA which are not included in the classification criteria and their possible use in patients with the suspicion of APS, but who do not fulfil the current criteria.

These recommendations are based on the data which are available now, and they must be considered as an aid to decision-making by the doctor directly involved in caring for a patient with APS. Although these recommendations are considered to be a tool for use in doctors’ decision-making, the decision of doctors who are experts in APS must also be taken into account, together with the opinion shared with the patient.

Research agendaAfter the systematic review of existing scientific evidence for treating primary APS which was undertaken to prepare these recommendations, the panel of experts considers that many aspects should be included in the future research agenda. The following may be mentioned, among others:

Obstetric APS:

- -

More randomised clinical trials are required, with good methodological quality, to study the efficacy of LMWH and ASA at low doses in the treatment of obstetric APS in its different variants, as well as the use of other treatments in isolation or combined.

- -

There is a need to carry out well-designed long-term studies on the monitoring and individualised treatment of patients with obstetric APS after pregnancy.

- -

Good quality studies are necessary on the need to administer antithrombotic prophylaxis to patients with APS who are going to be subjected to assisted reproduction techniques.

Refractory obstetric APS:

- -

New tools or scores must be developed which make it possible to identify the patients with obstetric APS who are at high risk of recurrence.

- -

It is necessary to design multicentre prospective studies that make it possible to determine the role of HCQ or prednisone in the treatment of refractory obstetric APS.

Recurrent APS:

- -

Prospective multicentre studies are needed to make it possible to determine the role of HCQ in the prevention of thrombotic recurrence in high risk patients.

- -

It is necessary to design prospective multicentre studies that make it possible to determine the role of rituximab in the prevention of thrombotic recurrence in high risk patients.

Catastrophic APS:

- -

New tools or scores have to be developed to enable identification of those individuals with APS who are at high risk of developing catastrophic APS.

- -

More prospective multicentre studies are needed which make it possible to determine the role of biological therapy in patients with catastrophic APS that is refractory to triple therapy.

Fundación Española de Reumatología.

Conflict of interestsRafael Cáliz Cáliz has received financing from Abbvie, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, MSD, UCB and GSK to attend courses/conferences, and he has received fees from SER for talks and writing chapters of books.

Víctor Manuel Martínez Taboada has received financing from Abbvie, Menariniand and Pfizer to attend courses/conferences; he has received fees from Abbvie, MSD, Novartis, BMS and Roche for talks; financing from Servier for participating in research; economic aid from Roche to finance an independent research project, and economic aid from Servier and Hospira for consultancy for pharmaceutical companies or other technologies.

María Galindo has received financing from Pfizer, UCB, Lilly, Abbvie, Menarini and MSD to attend courses/conferences; fees from Rubió, Abbvie, MSD, UCB, BMS, Lilly and GSK for talks, and economic aid from GSK, Lilly, Celgene and UCB for consultancy for pharmaceutical companies or other technologies.

Francisco Javier López Longo has received financing from MSD, GSK, UCB and Pfizer to attend courses/conferences; fees from GSK and Roche for talks; financing from UCB and Roche for educational programs or courses; financing from GSK for taking part in research, and economic aid from Sanofi-Aventis for consultancy for pharmaceutical companies or other technologies.

María Ángeles Martínez Zamora has no conflict of interests to declare.

Amparo Santamaría Ortiz has received financing from Pfizer, Bayer, Boehringer, Daichi Saikyo, Sanofi, Leopharma, Rovi, CSL Behring, Sobi, Werfen, Octopharma, NovoNordisk and Roche to attend courses/conferences, and fees for talks and for consultancy for pharmaceutical companies or other technologies.

Olga Amengual Pliego has no conflict of interests to declare.

María José Cuadrado Lozano has no conflict of interests to declare.

María Paloma Delgado Beltrán has no conflict of interests to declare.

The group of experts of this work would like to thank Mercedes Guerra Rodríguez, a SER researcher, for her help in the search strategies for evidence, and Dr. Sixto Zegarra Mondragón for his help in revising the systematic review reports. We would also like to thank Dr. Federico Díaz González, the director of the SER Research Unit, for his participation in the revision of the final manuscript and for helping to maintain the independence of this document.

Please cite this article as: Cáliz Cáliz R, Díaz del Campo Fontecha P, Galindo Izquierdo M, López Longo FJ, Martínez Zamora MÁ, Santamaria Ortiz A, et al. Recomendaciones de la Sociedad Española de Reumatología sobre síndrome antifosfolípido primario. Parte II: síndrome antifosfolípido obstétrico y situaciones especiales. Reumatol Clin. 2020;16:133–148.