The therapeutic efficacy of monoclonal antibodies in systemic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases is unquestionable but, with frequency, their contribution to treatment is compromised by the development of adverse events and the loss or absence of efficiency. Moreover, when a parenteral route is used for their administration, there can be an inadequate adhesion on the part of the patient. For these reasons, it is important to have effective and safe therapeutic options that extend the available therapeutic arsenal and facilitate patient adhesion.1,2 The design and therapeutic application of molecules directed against phosphodiesterase enzymes (phosphodiesterase [PDE]) for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases is very promising. This editorial summarizes the origin and the mechanism of action of PDE4 inhibitors, especially apremilast, because of its recent entry into the Spanish market.

The anti-inflammatory potential of PDE inhibitors is known since the beginning of the 1970s, and the use of selective molecules directed against PDE4 for the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases has been demonstrated in recent years.3,4 After the first generation of the nonselective PDE4 inhibitor, rolipram, was interrupted because of its adverse effects (mainly, nausea and vomiting).5 Another selective PDE4 inhibitor, roflumilast, was developed (Daxas®, Takeda). This drug was authorized in 2011 for the treatment of severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) associated with chronic bronchitis in adults and is being tested in patients with severe bronchial asthma.6,7 Other inhibitors, like cilomilast (Ariflo®, GlaxoSmithKline), are also being evaluated for the treatment of COPD.8 Drugs like CHF6001 (Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A.) and GSK256066 are now in phase II trials for the treatment of bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis, respectively.9,10 Other phase II clinical trials are evaluating PDE4 inhibitors, like ibudilast (MediciNova) in bronchial asthma, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, methamphetamine dependence and chronic migraine11 (www.clinicaltrials.gov). Drugs like NCS 613, ASP3258 and etazolate have been found to be effective in animal models as anti-inflammatory agents in pulmonary diseases and, at the present time, their antidepressant action is also being studied.12–14

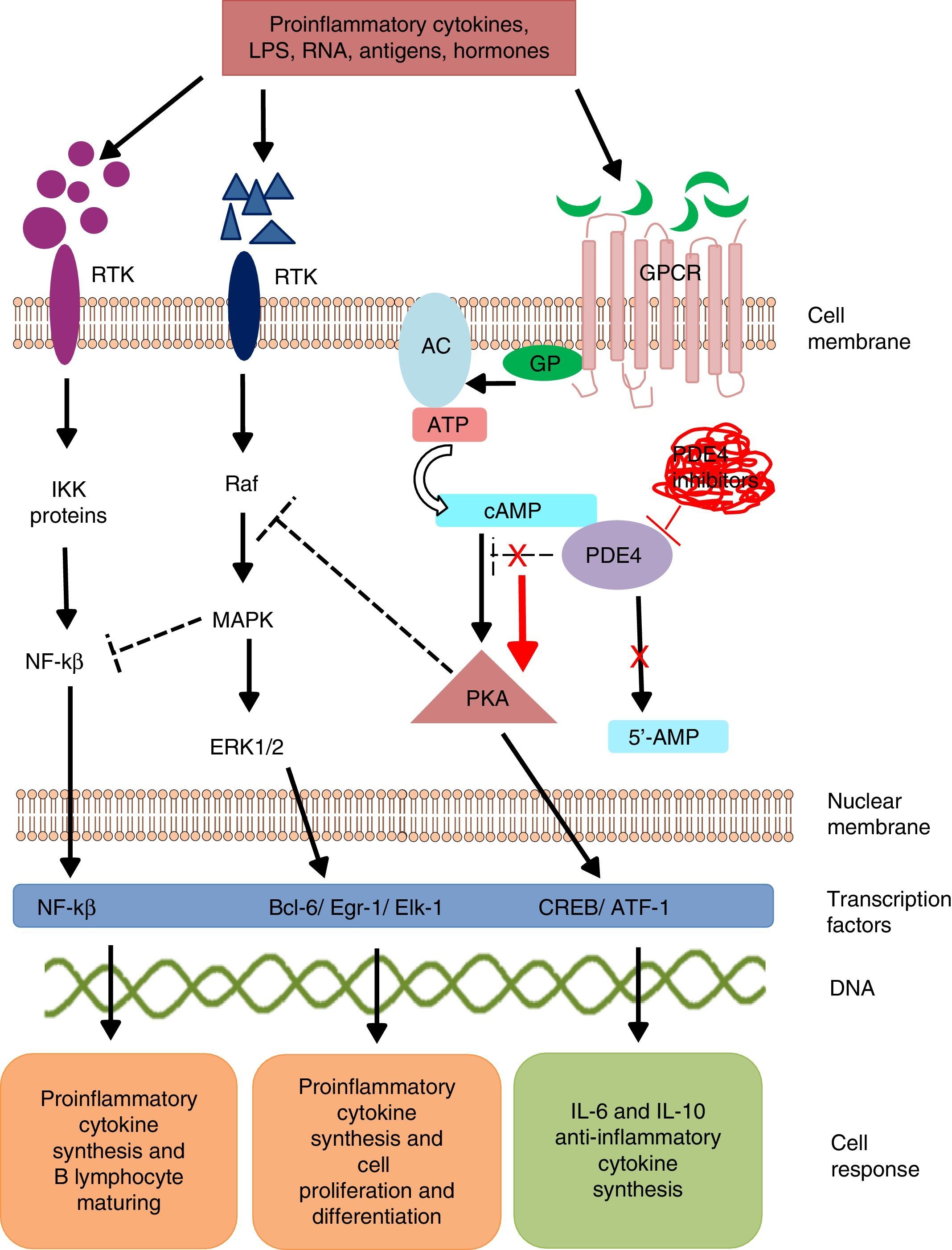

Intracellular signaling mechanisms modulate the synthesis and production of pro- and anti-inflammatory signals and factors, which act on a local and/or systemic level. These signaling mechanisms are triggered by the bonding of a specific ligand to cell surface receptors. These receptors are activated in the presence of extracellular stimuli like lipopolysaccharides, leukotrienes, nucleic acids, prostaglandins, neuropeptides, cytokines and chemokines, which trigger a cascade-like response within the cell.15 The activation of transmembrane receptors of 7 domains or G protein (GP)-coupled receptors (GPCR) induces a conformational change in its structure and subsequent GP activation.16 G protein is a heterotrimeric enzyme, and in its process of activation, it divides and activates enzymes like adenylate and/or guanylate cyclase (Fig. 1). These enzymes, in turn, convert adenosine triphosphate (ATP) into cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). The increase in the cAMP concentration favors the activation of enzymes like protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase G (PKG).17 These signaling mechanisms are fundamental for translating extracellular stimuli into signals indicating cell maturing and differentiation and the production of cytokines.

Mechanism of action of PDE4 and effect of its inhibition. AC, adenylate cyclase; 5′-AMP, 5′-adenylic acid; ATF, activating transcription factor 1; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Bcl-6, B-cell lymphoma protein 6; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CREB, cAMP response element-binding protein; Egr-1, early growth response protein 1; Elk-1, E-26-like protein 1; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GP, G protein; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptors; IKK, inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; NFKB, nuclear factor KB; PDE4, phosphodiesterase type 4; PKA, protein kinase A; Raf, rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma protein kinases; RTK, receptor tyrosine kinases.

Phosphodiesterases are a family of enzymes that catalyze the inactivation of nucleotides cAMP and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) into 5′-AMP and 5′-GMP, respectively. Thus, PDE control the concentration of these nucleotides and activate them to act on the intracellular signaling cascades.18

Phosphodiesterase phosphorylation favors:

- I.

The transcription of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and activating transcription factor-1 (ATF-1), which induce the synthesis of anti-inflammatory cytokines and regulate the expression of genes related to cell growth and survival.19

- II.

Indirect inhibition of transcription factor, the nuclear factor-kβ (NF-kβ), by means of the block by tyrosine kinase enzymes like mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK).20 Nuclear factor-kβ is an indispensable protein complex in the activation of innate and acquired immunity, a response to cell stress, inflammation and B-lymphocyte maturation.21

Intracellular signaling by means of PKA regulates cell maturation and favors the synthesis of anti-inflammatory signals that inhibit the production of inflammatory mediators. Low cAMP concentrations favor inflammation due to the increase in IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor-α, γ-interferon, and chemokine C–X–C motif ligand 9 (CXCL9) and CXC10, and when the concentration increases, an anti-inflammatory response from anti-inflammatory cytokines is induced by the production of IL-6 and IL-10.22

Mammals are reported to have 11 PDE families (PDE1-11) which encode up to 100 different isoforms. These enzyme are classified in accordance with their biochemical properties, molecular structure, response to specific stimuli and/or affinity for cyclic nucleotides. For example, some of these proteins, like PDE5, PDE6 and PDE9, selectively hydrolyze cGMP, and others, such as, PDE4, PDE7 and PDE8, hydrolyze cAMP; whereas PDE1, PDE2, PDE3, PDE10 and PDE11 can hydrolyze both cyclic nucleotides.23 Phosphodiesterases are located in the brain, bronchi, gastrointestinal tract, spleen, lung, heart, kidney and testicles, in endothelial cells, keratinocytes, synovial membrane, neurons, T and B lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils and neutrophils.24 PDE4 have 4 isoforms (PDE4A, PDE4B, PDE4C and PDE4D), all of which are expressed in the majority of leukocytes. Isoforms PDE4A and B have a relevant role in inflammation as they are expressed mainly in T and B lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils.25–27 They regulate multiple physiological processes related to the immune response and inflammation. The selective inhibition of PDE4 impedes the hydrolysis of cyclic nucleotides, favoring the increase in the concentration of intracellular cAMP and the activation of signaling pathways for the synthesis of CREB and ATF-1.

Apremilast (Otezla®, Celgene Corporation, Summit, NJ, USA), a small synthetic molecule for oral administration, is the first drug of this class to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis (March 2014) and for plaque psoriasis in adults (September 2014). In Europe, in has been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in January of 2015, and can now be purchased in Spain as of February of 2016. The dose shown in the technical specifications is 30mg 2 twice a day, using an initial program for escalating the dose to reduce gastrointestinal adverse events; it has been found to be effective and have a good safety profile in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis.28–30

After the administration of apremilast the peak plasma concentration is reached in 2–6h, with a bioavailability of 73%, a half-life of 8.2h and a metabolic catabolism via several routes, including that of cytochrome P450 (CYP); only 3% of the dose is excreted unchanged in urine.31 The bioavailability is reduced when administered concomitantly with potent CYP inducers (such as, for example, rifampicin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, phenytoin and St. John's wort), and the clinical response, may be reduced, as well. Significant pharmacokinetic interactions have not been reported with CYP inhibitors, like oral contraceptives, ketoconazole or methotrexate.32,33

Phosphodiesterases are expressed extensively in the central nervous center, making them especially attractive for the design of new targets for the treatment of psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders; this would explain that nausea, vomiting and headache are common adverse effects of the use of apremilast. The possible development of dyspepsia, diarrhea, gastroenteritis, upper airway tract infections and fatigue has also been reported.3 There is no evidence of opportunist infections, tuberculosis reactivation, neoplastic diseases, demyelination or lupus-like syndrome; likewise, changes in laboratory findings (hemoglobin, complete blood cell count and liver function), blood pressure or electrocardiography are not considered issues at this point.

At the present time, apremilast is in the clinical trial phase for approval in other chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, including ankylosing spondylitis, Alzheimer's disease, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, atopic dermatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and Behçet's disease.

How can we benefit from having a new therapeutic target with a completely different mechanism of action? Despite the recent development and marketing of monoclonal antibodies against the protein p40 subunit shared by IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab) and I-17A (secukinumab), the therapeutic options were reduced until now to disease-modifying drugs and monoclonal antibodies directed against tumor necrosis factor. The modulation of other therapeutic targets offers the availability of other treatment options for our patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis, since approximately 30% of the patients do not respond or respond inadequately to the existing therapeutic options. Apremilast has demonstrated its efficacy in patients who are refractory to conventional treatments, including monoclonal antibodies. One of its most important advantages is oral administration, which facilitates the adherence of the patient to treatment. In this regard, and because of the results obtained in recent years with other protein inhibitors associated with intracellular signaling pathways, such as Janus protein tyrosine kinases (JAK kinases). Oral drugs could represent an effective and safe option in the treatment of different chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, reducing the costs associated with their administration.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of InterestDHF: nothing to declare. LV: Abbvie, Roche Farma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, UCB, MSD and GSK.

The authors wish to thank Drs. Francisco Javier López Longo, Juan Carlos Nieto (Rheumatology Department, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain) and Gustavo Centeno Soto (Clinical Pharmacology Department, Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Madrid,Spain) for the critique and the corrections suggested for this manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Hernández-Flórez D, Valor L. Inhibidores selectivos de fosfodiesterasas, una nueva opción terapéutica en inflamación y autoinmunidad. Reumatol Clin. 2016;12:303–306.