To develop multidisciplinary recommendations based on available evidence and expert consensus for the therapeutic management of patients with refractory Behçet’s syndrome (BS) (difficult to treat, severe resistant, severe relapse) to conventional treatment.

MethodsA group of experts identified clinical research questions relevant to the objective of the document. These questions were reformulated in PICO format (patient, intervention, comparison and outcome). Systematic reviews of the evidence were conducted, the quality of the evidence was evaluated following the methodology of the international working group Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). After that, the multidisciplinary panel formulated the specific recommendations.

Results4 PICO questions were selected regarding the efficacy and safety of systemic pharmacological treatments in patients with BS with clinical manifestations refractory to conventional therapy related to mucocutaneous and/or articular, vascular, neurological parenchymal and gastrointestinal phenotypes. A total of 7 recommendations were made, structured by question, based on the identified evidence and expert consensus.

ConclusionsThe treatment of most severe clinical manifestations of BS lacks solid scientific evidence and, besides, there are no specific recommendation documents for patients with refractory disease. With the aim of providing a response to this need, here we present the first official Recommendations of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology for the management of these patients. They are devised as a tool for assistance in clinical decision making, therapeutic homogenisation and to reduce variability in the care of these patients.

Elaborar recomendaciones multidisciplinares, basadas en la evidencia disponible y el consenso de expertos, para el manejo terapéutico de los pacientes con síndrome de Behçet (SB) refractario (difícil de tratar, resistente grave, recidivante grave) al tratamiento convencional.

MétodosUn panel de expertos identificó preguntas clínicas de investigación relevantes para el objetivo del documento. Estas preguntas fueron reformuladas en formato PICO (paciente, intervención, comparación, outcome o desenlace). A continuación, se realizaron revisiones sistemáticas, la evaluación de la calidad de la evidencia se realizó siguiendo la metodología del grupo internacional de trabajo Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE). Tras esto, el panel multidisciplinar formuló las recomendaciones.

ResultadosSe seleccionaron 4 preguntas PICO relativas a la eficacia y seguridad de los tratamientos farmacológicos sistémicos en los pacientes con SB con manifestaciones clínicas refractarias a terapia convencional, relacionadas con los fenotipos mucocutáneo y/o articular, vascular, neurológico-parenquimatoso y gastrointestinal. Se formularon un total de 7 recomendaciones estructuradas por pregunta, en base a la evidencia encontrada y el consenso de expertos.

ConclusionesEl tratamiento de las manifestaciones clínicas más graves del SB carece de evidencia científica sólida y no existen documentos de recomendaciones específicas para los pacientes con enfermedad refractaria a la terapia convencional. Con el fin de aportar una respuesta a esta necesidad, se presenta el primer documento de recomendaciones de la Sociedad Española de Reumatología específicas para el abordaje terapéutico de estos pacientes, que servirá de ayuda en la toma de decisiones clínica y la reducción de la variabilidad en la atención.

Behçet’s syndrome (BS) is a polysymptomatic entity whose definition is based on clinical diagnostic or classification criteria.1 It is considered a mixed pattern disease with an immunological basis, halfway between autoinflammatory syndromes and autoimmune diseases (components of the innate and adaptive immune system). Triggers can be infectious agents and environmental factors in genetically predisposed individuals, with the absence of specific autoimmunity. The pathological substrate is a vasculitis that preferentially affects capillaries and venules, although it can affect veins and arteries of any size.2

It has a relapsing and remitting course, with high morbidity depending on the organ or system involved. It can present with oral and genital ulcers, different types of skin lesions (papulopustular, lesions similar to erythema nodosum, cutaneous vasculitis, acneiform nodules and folliculitis), arthralgia or arthritis, eye disease (anterior or posterior uveitis or panuveitis with retinal vasculitis), artery aneurysms, thrombosis in arteries and veins of any calibre, parenchymal brain lesions, thrombosis of the cerebral sinuses and intestinal involvement, mostly in the form of intestinal ulcers.3 These clinical manifestations are grouped into differential phenotypic aggregates (clusters) (neuro-ocular, mucocutaneous-articular, vascular and intestinal) with variable aetiopathogenic bases that condition different responses to treatments.4

The evidence-based therapeutic approach to BS still has many unmet needs.5

In 2018, the update of the recommendations developed in 2008 by the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) for the treatment of BS was published,6,7 based on a bibliographic review that went up to the year 2016.8,9 This document establishes a conventional treatment framework based on randomised clinical trials (RCTs) (uveitis, mucocutaneous lesions, arthritis) or on observational data (thrombosis, aneurysms, neurological and intestinal lesions), and establishes some recommendations for refractory or recurrent cases with poor response to initial treatment. These patients may suffer from high morbidity and mortality and there are no consensual recommendations for their management. Furthermore, the efforts of the OMERACT group to define areas of intervention and improvement seem insufficient for their application in refractory patients,10 Recently, OMERACT has proposed a set of domains to be evaluated in clinical trials, but has not yet defined the levels of therapeutic response, refractoriness, or the tools to evaluate them.11 The Core Set consists of 5 mandatory domains that must be evaluated in all BS trials. These domains are overall disease activity, new organ involvement, quality of life, adverse events (AEs), and mortality. In addition to these, there are mandatory subdomains that must be assessed in organ-specific trials and other important but optional subdomains that could be evaluated in keeping with the purpose of the trial. Finally, there are domains and subdomains in the research agenda.11

Based on the above, and in order to respond to this healthcare need, this document of specific recommendations has been prepared to address the most frequent clinical phenotypes of refractory or recurrent BS (mucocutaneous-articular, vascular, parenchymal neurological and intestinal), to help clinicians directly involved in its management in decision-making.

MethodsTo develop these recommendations, an amalgamation of scientific evidence and consensus techniques were used, which reflected the consensus of experts based on the available evidence and their clinical experience. The process for developing the recommendations was as follows:

Creation of a workgroup. A multidisciplinary work group was formed comprised of 6 rheumatologist members of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER for its initials in Spanish), a patient, an internist and a haematologist. The coordination of the clinical and methodological aspects was carried out, respectively, by 2 rheumatologists as main investigators and a methodology specialist, technician from the SER Research Unit. The group formed the recommendations development group (DG).

Identification of key areas. The DG established the scope and content of the document. Clinical research questions that could have the most impact to offer in clinical practice regarding the management of refractory BS were identified. These questions were formulated in PICO format: Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome.

Bibliographic search. A bibliographic search of the scientific evidence was carried out in the PubMed (MEDLINE), EMBASE (Elsevier) and Cochrane Library (Wiley Online) databases until January 2022. The process was completed with a manual search in the references of the identified studies, as well as other references that the reviewers and experts considered of interest. Complete articles published in indexed scientific journals were considered.

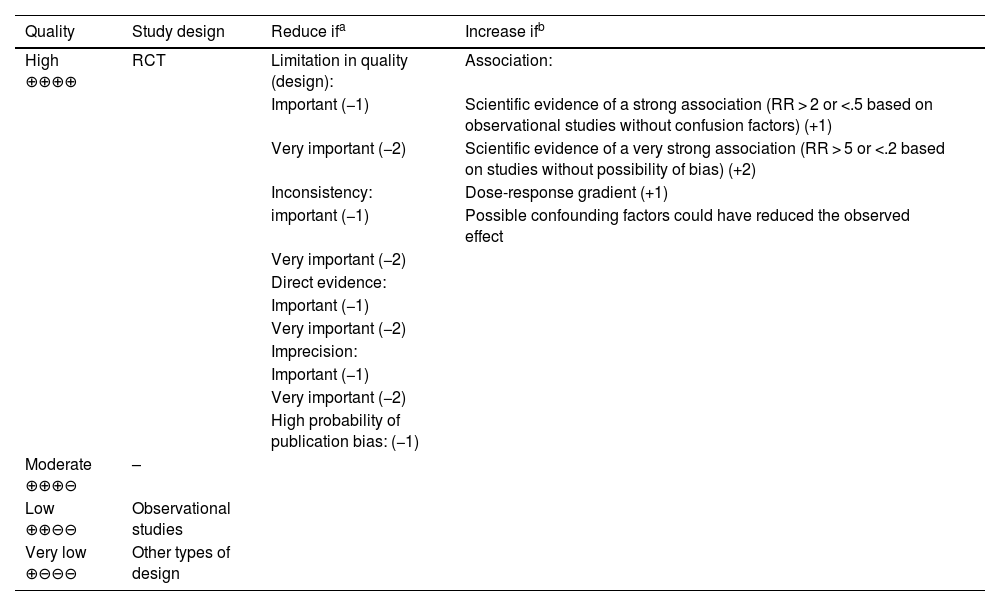

Analysis and synthesis of scientific evidence. Systematic reviews (SR) of the available scientific evidence were conducted. Assessment of the quality or certainty of the evidence was made following the methodology of the international work group Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE).12 To determine the quality of evidence, in addition to the design and methodological quality of individual studies, the GRADE system involves the evaluation of other factors that influence confidence in study estimates, such as the consistency of results between studies, the direct/indirect nature of the evidence (indirect comparison of the interventions of interest and/or differences in the population, the intervention, the comparator and/or the results of interest with respect to the objectives of this report), the precision of estimates and publication bias. As Table 1 shows, considering a combination of these components, the quality of evidence for each critical or important outcome was classified and defined as high ⊕⊕⊕⊕ (very unlikely that new studies will change the estimate), moderate⊕ ⊕⊕⊖ (new studies are likely to change our confidence in the outcome), low ⊕⊕⊖⊖ (new studies are very likely to impact our confidence in the outcome and could modify it) and very low ⊕⊖ ⊖⊖ (any estimated outcomes are highly doubtful). The outcomes considered in each question and their importance can be consulted in Appendix A supplementary material (Annex I).

Classification of the quality of evidence in the GRADE system.

| Quality | Study design | Reduce ifa | Increase ifb |

|---|---|---|---|

| High ⊕⊕⊕⊕ | RCT | Limitation in quality (design): | Association: |

| Important (−1) | Scientific evidence of a strong association (RR > 2 or <.5 based on observational studies without confusion factors) (+1) | ||

| Very important (−2) | Scientific evidence of a very strong association (RR > 5 or <.2 based on studies without possibility of bias) (+2) | ||

| Inconsistency: | Dose-response gradient (+1) | ||

| important (−1) | Possible confounding factors could have reduced the observed effect | ||

| Very important (−2) | |||

| Direct evidence: | |||

| Important (−1) | |||

| Very important (−2) | |||

| Imprecision: | |||

| Important (−1) | |||

| Very important (−2) | |||

| High probability of publication bias: (−1) | |||

| Moderate ⊕⊕⊕⊖ | – | ||

| Low ⊕⊕⊖⊖ | Observational studies | ||

| Very low ⊕⊖⊖⊖ | Other types of design |

RCT: randomized clinical trial; GRADE: Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; RR: relative risk.

Source: Atkins et al.12

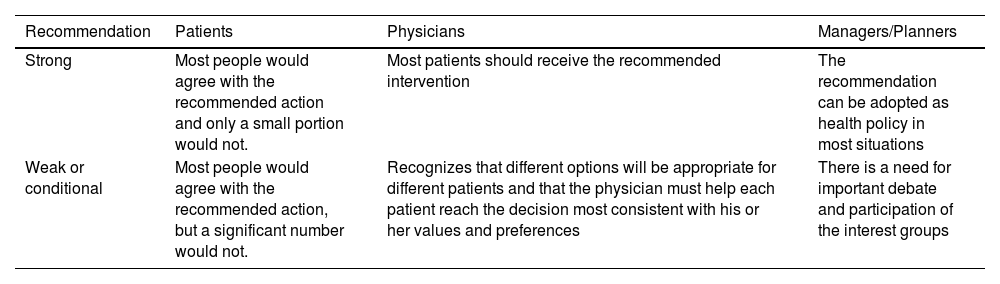

Formulation of recommendations. Once the critical reading and synthesis was completed, the DG proceeded to formulate specific recommendations based on scientific evidence. This formulation was based on "formal evaluation" or "reasoned judgment", previously summarising the evidence for each of the clinical questions and taking into account the quality or certainty of the scientific evidence identified, the values and preferences of the patients, the balance between desirable and undesirable effects of the interventions and aspects such as equity, acceptability and feasibility of their implementation, following the GRADE methodology. To do this, frameworks were used that assist in the process of moving from evidence to recommendations (evidence to decision). At the end of this process, the strength (weak or strong) and direction (for or against) of the recommendations were determined, with different implications for their different users (Table 2).

Implications of the strength of Recommendation in the GRADE system.

| Recommendation | Patients | Physicians | Managers/Planners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | Most people would agree with the recommended action and only a small portion would not. | Most patients should receive the recommended intervention | The recommendation can be adopted as health policy in most situations |

| Weak or conditional | Most people would agree with the recommended action, but a significant number would not. | Recognizes that different options will be appropriate for different patients and that the physician must help each patient reach the decision most consistent with his or her values and preferences | There is a need for important debate and participation of the interest groups |

GRADE: Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation.

Source: Atkins et al.12

Furthermore, on occasions the DG considered that there were some important aspects that needed emphasis, but for which there was no quality scientific evidence. These cases are related to aspects of treatment considered good clinical practice that would not normally be questioned. These aspects were valued as points or recommendations of good clinical practice (GCP).

External review and public exposure. A draft of the final document was sent to professionals selected for their knowledge of BS for independent external review, with the aim of increasing the external validity of the document and ensuring the accuracy of the recommendations. Subsequently, the document was subjected to a period of public exhibition by members of the SER and different interest groups (other scientific societies, industry, etc.), in order to collect their assessment and scientific argumentation of the methodology or the recommendations.

Clinical research questionsThe recommendations addressed 4 clinical questions:

- -

In patients with refractory mucocutaneous and/or joint phenotype of Behçet’s syndrome, what is the efficacy and safety of systemic pharmacological treatments?

- -

In patients with refractory vascular phenotype of Behçet’s syndrome, what is the efficacy and safety of systemic pharmacological treatments?

- -

In patients with refractory neurological-parenchymal phenotype of Behçet’s syndrome, what is the efficacy and safety of systemic pharmacological treatments?

- -

In patients with refractory gastrointestinal (GI) phenotype of Behçet’s syndrome, what is the efficacy and safety of systemic pharmacological treatments?

The reformulation of the questions in PICO format can be consulted in Appendix Annex I of the supplementary material, at the beginning of each question section.

Prior considerationsThe target population of these recommendations are those patients with severe manifestations that are difficult to treat and that correspond to any of the clinical phenotypes proposed in recent literature. We broadly define difficult-to-treat cases as refractory (from the Latin refractarius: obstinate, pertinacious), i.e., with persistent activity despite conventional treatment. We include within this definition recurrent cases, with recurrent severe manifestations despite conventional treatment. After reviewing the literature, we decided that we should also consider as difficult to treat those patients with particularly severe initial manifestations, in whom the results expected with conventional therapies are unsatisfactory.

Ocular manifestationsOcular manifestations of BS are considered part of the neuro-ocular phenotype (cluster).4 According to the classic definition, uveitis can be classified by its laterality (unilateral or bilateral) and by its pattern of involvement (anterior, intermediate, posterior and panuveitis). The most common pattern of involvement in patients with BS is bilateral panuveitis, which usually presents a recurrent course. Although anterior uveitis is classically described as hypopyonic uveitis, most cases do not have purulent exudate in the anterior chamber. Recurrent focal retinal infiltrates (“white spots”) and papillitis may also be observed, which can cause progressive visual loss.13 Occlusive retinal vasculitis is the most serious ocular manifestation in BS due to ischaemic involvement of the macula that can lead to permanent blindness. The Standardisation of Uveitis Nomenclature group published its BS14 uveitis classification criteria.

Recently, a group of rheumatologists and ophthalmologists coordinated by the SER Research Unit prepared a document of recommendations for the treatment of non-infectious, non-neoplastic uveitis not associated with demyelinating disease. Therefore, with regard to the treatment of ocular involvement in patients with BS, we recommend consulting this document, whose recommendations for refractory patients are detailed in Appendix A supplementary material (Annex II) and can be consulted on the SER website: https://www.ser.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Recomendaciones-SER-sobre-Tratamiento-de-la-Uve%C3%ADtis_DEF.pdf.

Vedolizumab and apremilast in gastrointestinal BSTo answer the question about enteric BS, neither vedolizumab nor apremilast was included in the medications to be reviewed. However, the search identified 2 references of interest.

Arbrile et al.15 15 published the case of a 49-year-old patient with erythema nodosum, orogenital thrush, and active intestinal involvement despite previous treatment with azathioprine and several biologics (adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, and certolizumab), which responded to vedolizumab.15 This was administered intravenously at a dose of 300 mg at 0, 2 and 6 weeks, and every 4 weeks thereafter. After the second dose, the patient presented a marked improvement in intestinal, skin and joint symptoms, achieving clinical remission after 6 months of treatment.

In a multicenter series of 51 cases of BS treated with apremilast in Spain,16 a favourable clinical response was described in 2 patients with ileitis.

Myelodysplastic syndrome associated with trisomy 8In the literature review of the question of patients with GI BS, we found a series of isolated case studies in patients who initially suffered from trisomy 8-associated myelodysplastic syndrome and who also had manifestations of GI BS. We asked ourselves if this group of patients would be among the patients for whom we wanted to make the recommendation. When reviewing the articles we found that patients behaved very differently from GI BS, since they did not improve with monoclonal antibodies inhibitors of tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and only improved when treating the myelodysplastic syndrome (with bone marrow transplant in many cases), so we considered these cases outside the scope of this recommendations document.17

AlemtuzumabThere are data in the literature of refractory BS successfully treated with alemtuzumab (anti-CD52). One study included 32 patients who achieved partial or complete remission in 84% of cases, with non-negligible AEs (27% infusion reactions and 25% development of symptomatic thyroid disease).18 This drug was not taken into account when developing the recommendations, since the publication did not differentiate patients based on their clinical manifestations, and we therefore cannot assess the response in the different phenotypes of BS.

Paediatric Behçet’s syndromeIn the initial approach to these recommendations, we decided to exclude the population of children and adolescents under 18 years of age due to the absence of relevant studies for their general management, and specifically for difficult refractory or severely relapsing cases.19

There are small but relevant differences between young people and adults. In general, paediatric patients take longer to develop the full disease phenotype. GI tract involvement, neurological findings, arthralgias, and a positive family history are more common in children, while genital and vascular lesions are more common in adult patients. Therapeutic recommendations are, so far, similar to those for adults. Although there is considered to be a better prognosis, with a lower severity score and activity index in children, there may be severe cases that may benefit from the recommendations for adults in this document.

Until now, the only set of criteria recommended for paediatric BS is that of the Paediatric Behçet's Disease (PEDBD) study group.20

The pathergy test is not included and oral aphthosis is not considered a mandatory criterion. All symptom categories carry the same weight, due to the lack of knowledge of their respective frequencies in the general paediatric population.

Although the criteria applied in adults, both those of the ISG21 and those of the ICBD,22 can also be used, Batu et al. reported a sensitivity and specificity of 52.9 and 100% for the ISG criteria, and 73.5% and 97.7% for the PEDBD criteria, respectively.23 On the other hand, Ekinci et al. found a sensitivity and specificity of 87.5% and 100% for the ISG criteria, 93.7% and 98.1% for the ICBD criteria, and 93.7% and 96.2% for the PEDBD criteria, respectively.24 Finally, in a patient with atypical PFAPA traits, we must take into account both BS and, in patients with BS traits in early childhood, consider A2025 haploinsufficiency syndrome.

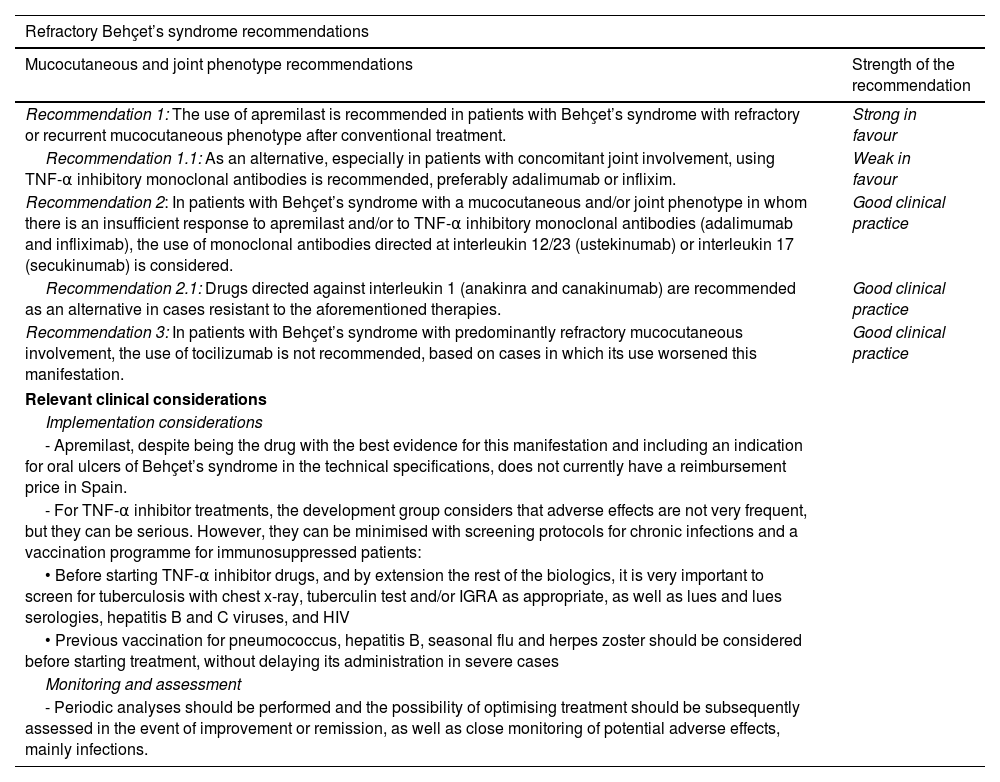

ResultsA total of 7 recommendations were formulated, divided by disease phenotype (Table 3). All additional information on the sections described below can be consulted in Supplementary Appendix Amaterial (Annex I), which shows the process followed by the DG to get from the evidence to the recommendations, including the evidence in narrative or tabulated form and the judgments adopted. In addition, it is possible to consult the therapeutic algorithms for each manifestation addressed (Appendix A Annex III).

SER recommendations on the treatment of refractory Behçet’s syndrome.

| Refractory Behçet’s syndrome recommendations | |

|---|---|

| Mucocutaneous and joint phenotype recommendations | Strength of the recommendation |

| Recommendation 1: The use of apremilast is recommended in patients with Behçet’s syndrome with refractory or recurrent mucocutaneous phenotype after conventional treatment. | Strong in favour |

| Recommendation 1.1: As an alternative, especially in patients with concomitant joint involvement, using TNF-α inhibitory monoclonal antibodies is recommended, preferably adalimumab or inflixim. | Weak in favour |

| Recommendation 2: In patients with Behçet’s syndrome with a mucocutaneous and/or joint phenotype in whom there is an insufficient response to apremilast and/or to TNF-α inhibitory monoclonal antibodies (adalimumab and infliximab), the use of monoclonal antibodies directed at interleukin 12/23 (ustekinumab) or interleukin 17 (secukinumab) is considered. | Good clinical practice |

| Recommendation 2.1: Drugs directed against interleukin 1 (anakinra and canakinumab) are recommended as an alternative in cases resistant to the aforementioned therapies. | Good clinical practice |

| Recommendation 3: In patients with Behçet’s syndrome with predominantly refractory mucocutaneous involvement, the use of tocilizumab is not recommended, based on cases in which its use worsened this manifestation. | Good clinical practice |

| Relevant clinical considerations | |

| Implementation considerations | |

| - Apremilast, despite being the drug with the best evidence for this manifestation and including an indication for oral ulcers of Behçet’s syndrome in the technical specifications, does not currently have a reimbursement price in Spain. | |

| - For TNF-α inhibitor treatments, the development group considers that adverse effects are not very frequent, but they can be serious. However, they can be minimised with screening protocols for chronic infections and a vaccination programme for immunosuppressed patients: | |

| • Before starting TNF-α inhibitor drugs, and by extension the rest of the biologics, it is very important to screen for tuberculosis with chest x-ray, tuberculin test and/or IGRA as appropriate, as well as lues and lues serologies, hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV | |

| • Previous vaccination for pneumococcus, hepatitis B, seasonal flu and herpes zoster should be considered before starting treatment, without delaying its administration in severe cases | |

| Monitoring and assessment | |

| - Periodic analyses should be performed and the possibility of optimising treatment should be subsequently assessed in the event of improvement or remission, as well as close monitoring of potential adverse effects, mainly infections. | |

| Vascular phenotype recommendations | Strength of the recommendation |

|---|---|

| Recommendation 4: In patients with Behçet’s syndrome with a refractory or recurrent vascular phenotype after conventional treatment, the use of TNF-α inhibitory monoclonal antibodies, preferably infliximab is recommended. Another option could be adalimumab | Strong in favour |

| Recommendation 4.1: Its use will also be evaluated in patients with severe vascular involvement at the beginning who require rapid control of inflammation | Good clinical practice |

| Recommendation 4.2: In cases of ineffectiveness of TNF-α inhibitors, tocilizumab is recommended as an alternative | |

| Recommendation 5: In patients with vascular phenotype Behçet’s syndrome, with thrombotic manifestations, in addition to immunosuppressive treatment, the following are recommended: | Good clinical practice |

| • For recurrent venous thrombotic disease, anticoagulation according to the general clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of venous thromboembolism | Good clinical practice |

| • For thrombosis in arterial territories, antiaggregation according to clinical practice guidelines and consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of acute ischaemic events | |

| Relevant clinical | |

| For TNF-α inhibitor treatments, the development group considers that adverse effects are not very frequent, but they can be serious. However, they can be minimised with screening protocols for chronic infections and a vaccination programme for immunosuppressed patients: | |

| • Prior to starting TNF-α inhibitor drugs, and by extension the rest of the biologics, it is very important to screen for tuberculosis with a chest x-ray, tuberculin test and/or IGRA as appropriate, as well as serology of lues and hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV | |

| • Previous vaccination for pneumococcus, hepatitis B, seasonal flu and herpes zoster should be considered before starting treatment, without delaying its administration in severe cases | |

| Monitoring and assessment | |

| - Periodic analyses should be performed and the possibility of optimising treatment should be subsequently assessed in the event of improvement or remission, as well as close monitoring of potential adverse effects, mainly infections in biological therapy and haemorrhagic events in anticoagulant treatment | |

| - For vitamin K antagonists, periodic monitoring of the INR should be carried out to adjust the dose of anticoagulant necessary to maintain the INR between 2 and 3 | |

| Neurological-parenchymal phenotype recommendations | Strength of the recommendation |

|---|---|

| Recommendation 6: In patients with refractory or recurrent neurological-parenchymal phenotype Behçet’s syndrome after conventional treatment, the use of TNF-α inhibitory monoclonal antibodies is recommended, preferably adalimumab or infliximab | Strong in favour |

| Recommendation 6.1: When TNF-α inhibitors are ineffective the DG recommends the use of tocilizumab, despite the limited evidence available. Another possible therapeutic option is rituximab | Good clinical practice |

| Relevant clinical considerations | |

| Implementation considerations | |

| - For TNF-α inhibitor treatments, the DG considers that adverse effects are not very frequent, but they can be serious. However, they can be minimised with screening protocols for chronic infections and a vaccination programme for immunosuppressed patients: | |

| • Prior to starting TNF-α inhibitor drugs and by extension the rest of the biologics it is very important to screen for tuberculosis with chest x-ray, tuberculin test and/or IGRA as appropriate, as well as blood serology, lues and hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV | |

| • Previous vaccination for pneumococcus, hepatitis B, seasonal flu and herpes zoster should be considered before starting treatment, without delaying its administration in severe cases. | |

| • Before starting rituximab and during follow-up, immunoglobulin levels should be determined | |

| Monitoring and assessment | |

| - Periodic analyses should be performed and the possibility of optimising treatment should be subsequently assessed in the event of improvement or remission, as well as close monitoring of potential adverse effects, mainly infections. | |

| Gastrointestinal phenotype recommendations | Strength of the recommendation |

|---|---|

| Recommendation 7: In patients with Behçet’s syndrome with refractory or recurrent gastrointestinal involvement after conventional treatment, the use of TNF-α inhibitory monoclonal antibodies is recommended, preferably adalimumab or infliximab | Strong in favour |

| Recommendation 7.1: Their use will also be assessed in patients with severe initial gastrointestinal involvement who require rapid control of inflammation | Good clinical practice |

| Recommendation 7.2: In cases refractory to TNF-α inhibitors, assessment of the use of tofacitinib is recommended, individualising the decision | |

| Relevant clinical considerations | |

| Implementation considerations | |

| - In TNF-α inhibitor treatments, the DG considers that adverse effects are not very frequent, but they can be serious. However, they can be minimised with screening protocols for chronic infections and a vaccination programme for immunosuppressed patients: | |

| • Prior to starting TNF-α inhibitor drugs, and by extension to the rest of the biologics, it is very important to screen for tuberculosis with chest x-ray, tuberculin test and/or IGRA as appropriate, as well as serology of lues, hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV | |

| • Previous vaccination for pneumococcus, hepatitis B, seasonal flu and herpes zoster should be considered before starting treatment, without delaying its administration in severe cases. | |

| Monitoring and assessment | |

| - Periodic analyses should be performed and the possibility of optimising treatment should be subsequently assessed in the event of improvement or remission, as well as close monitoring of potential adverse effects, mainly infections. | |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IGRA: interferon gamma release assay; INR: international normalized ratio; SER: Spanish Society of Rheumatology; TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor alpha.

In BS, skin involvement (folliculitis, pseudoerythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema multiforme or palpable purpura) can be observed in up to 3 out of 4 patients. Although less frequent (30%–50%), there may be joint involvement in the form of inflammatory arthralgias or asymmetric and non-erosive mono/oligoarthritis of large joints, with a predominance in the lower limbs. Treatment must be individualised based on the predominant clinical manifestations, their severity and the preferences of each patient, with the aim of avoiding permanent organic damage. Mucocutaneous and articular manifestations do not confer an increase in mortality from BS, but they do confer great morbidity. In 2008, the EULAR developed the first recommendations for the therapeutic management of patients with BS, subsequently updated in 2018.6,7

Recommendation 1: In patients with BS with refractory or recurrent mucocutaneous phenotype after conventional treatment, the use of apremilast is recommended (Strong recommendation in favour).

Recommendation 1.1: As an alternative, especially in patients with concomitant joint involvement, it is recommended to use TNF-α inhibitory monoclonal antibodies, preferably adalimumab or infliximab (Weak recommendation in favour).

Recommendation 2: In patients with a mucocutaneous and/or joint phenotype BS in whom there is an insufficient response to apremilast and/or to TNF-α inhibitory monoclonal antibodies (adalimumab and infliximab), the use of monoclonal antibodies directed at the interleukin (IL) 12/23 (ustekinumab) or IL-17 (secukinumab) is considered (GCP recommendation).

Recommendation 2.1: Drugs directed against IL-1 (anakinra and canakinumab) are recommended as an alternative in cases resistant to the aforementioned therapies (GCP Recommendation).

Recommendation 3: In patients with BS with predominantly refractory mucocutaneous involvement, the use of tocilizumab is not recommended based on cases in which its use worsened this manifestation (GCP Recommendation).

Relevant clinical considerations:

- •

Implementation considerations

- -

Apremilast, despite being the drug with the best evidence for this manifestation and including an indication for oral ulcers of BS in the technical specifications, does not currently have a reimbursement price in Spain.

- -

In the case of TNF-α inhibitor treatments, the DG considers that AEs are not so frequent, but they can be serious. However, they can be minimised with screening protocols for chronic infections and a vaccination programme for immunosuppressed patients:

- o

Prior to starting TNF-α inhibitor drugs, and by extension the rest of the biologics, it is very important to screen for tuberculosis with chest x-ray, tuberculin test and/or IGRA as appropriate, as well as lues serologies and hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV.

- o

Previous vaccination for pneumococcus, hepatitis B, seasonal influenza and herpes zoster should be considered before starting treatment, without delaying its administration in severe cases.

- o

- -

- •

Monitoring and assessment

- -

Periodic analyses should be performed and the possibility of optimising treatment should subsequently be assessed in the event of improvement or remission, as well as close monitoring of potential AEs, mainly infections.

- -

The positive results in the RELIEF RCT,26 supported by observational studies (OS) with balance of the results also in favour of its use16,27–29 and the fact that it is the only drug approved with an indication in the technical specifications sheet since 2019 for treatment of oral ulcers in BS, have led the DG to issue a strong recommendation in favour of apremilast as the first line of treatment for refractory mucocutaneous symptoms. Furthermore, TNF-α inhibitors are positioned as an alternative, preferably adalimumab30–33 or o infliximab,32,34–36 especially in patients with concomitant joint involvement. We should highlight the difficulty of implementing apremilast in our setting, since currently, despite having an indication for a specific domain of BS, it does not have a reimbursement price in Spain. Likewise, based on the evidence identified in the SR, which is determined to have low certainty, and the criteria of the DG, other biologics such as ustekinumab37,38 secukinumab,39,40 and lastly anakinra41–44 and canakinumab45 are considered as a therapeutic alternative for the mucocutaneous-articular phenotype. The EULAR 2018 recommendations state that IL-17 inhibition is not effective in the mucocutaneous domain,7 based on a clinical trial in uveitis that ended early due to failure to achieve the primary objective. However, the SR of the literature on which these recommendations are based identified 2 OSs subsequent to the EULAR recommendations that, despite their low quality, led the DG to conclude that secukinumab could be an effective alternative in the mucocutaneous and articular domain without ocular involvement.39,40

The EULAR 2018 recommendations state that IL-6 inhibition (tocilizumab) is not effective in the mucocutaneous domain, and may even worsen lesions, especially oral and genital ulcers.7 Likewise, the EG recommends not using tocilizumab in refractory mucocutaneous involvement based on the few published cases.46–48

EULAR recommends the use of interferon alfa in selected cases of mucocutaneous involvement and recurrent arthritis, but due to the age and low quality of the studies, the high percentage of AEs and the great variability in dosage and doses used,49–53 together with the limited experience in the use of this drug in our area, the DG does not establish any recommendation in this regard, since other safer and more effective therapeutic alternatives exist. Likewise, the absence of evidence on rituximab, limited to a single identified case,54 and limited clinical experience, do not allow us to establish a recommendation on its use in patients with mucocutaneous and articular phenotype of refractory BS.

Vascular manifestationsIn patients with refractory vascular phenotype of Behçet’s syndrome, what is the efficacy and safety of systemic pharmacological treatments?The prevalence of vascular involvement in people with BS ranges between 8% (Japan) and 62.3% (Morocco). Vascular manifestations can be a serious complication of BS, with considerable morbidity and mortality, especially in young men. It is estimated that between 18% and 29% of patients with BS present this type of manifestations,55 while other estimates speak of 15%–50%.56 BS can affect the entire vascular tree, veins and arteries of all sizes, causing recurrent vascular events, mainly superficial venous thrombosis and deep vein thrombosis of the lower limbs (DVT). It can also cause thrombosis in atypical locations, such as the cerebral venous sinus, suprahepatic veins (Budd-Chiari), intracardiac thrombi and arterial thromboses.

In this context, a deeper understanding of the risks derived from cardiovascular and thromboembolic complications will allow better long-term management of patients with BS. One of the main difficulties in assessing the evidence is the absence of clinical trials and studies that compare different drugs. Although several SRs have been carried out, there are no guidelines or recommendations in this regard.

Recommendation 4: In patients with BS with refractory or recurrent vascular phenotype after conventional treatment, the use of TNF-α, inhibitory monoclonal antibodies, preferably infliximab, is recommended. Another option could be adalimumab (Strong recommendation in favour).

Recommendation 4.1: Its use will also be evaluated in patients with severe vascular involvement at the beginning who require rapid control of inflammation (GCP Recommendation).

Recommendation 4.2: In case of ineffectiveness of TNF-α inhibitors, tocilizumab is recommended as an alternative (GCP Recommendation).

Recommendation 5: In patients with BS with vascular phenotype, with thrombotic manifestations, in addition to immunosuppressive treatment, the following is recommended:

- •

In cases of venous thrombotic disease, anticoagulation according to the general clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of venous thromboembolism (GCP Recommendation).

- •

In cases of thrombosis in arterial territories, antiaggregation according to clinical practice guidelines and consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of acute ischemic events (GCP Recommendation).

Relevant clinical considerations

- •

Implementation considerations

- -

In the case of TNF-α inhibitor treatments, the DG considers that AEs are not very frequent, but they can be serious. However, they can be minimised with screening protocols for chronic infections and a vaccination programme for immunosuppressed patients:

- o

Prior to starting TNF-α inhibitor drugs, and by extension to the rest of the biologics, it is very important to screen for tuberculosis with chest x-ray, tuberculin test and/or IGRA as appropriate, as well as lues and lues serologies, hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV.

- o

Previous vaccination for pneumococcus, hepatitis B, seasonal influenza and herpes zoster should be considered before starting treatment, without delaying its administration in severe cases.

- o

- -

- •

Monitoring and assessment

- -

Periodic analyses should be performed and the possibility of optimising treatment should be subsequently assessed in the event of achieving improvement or remission, as well as close monitoring of potential AEs, mainly infections in biological therapy and hemorrhagic events in anticoagulant treatment.

- -

In the case of vitamin K antagonists, periodic monitoring of the INR should be carried out to adjust the dose of anticoagulant necessary to maintain the INR between 2 and 3.

- -

Systematic search of the literature did not identify any RCTs. Management of the vascular manifestations of BS varies depending on the affected area, and the evidence for therapies is based on OS. Furthermore, there is no clear definition of refractoriness in vascular BS. In recurrent or refractory thrombosis, the DG has issued a strong recommendation in favour of using TNF-α inhibitors, preferably infliximab,32,34,57–74 although adalimumab can also be used,32,66,67,75,76 despite the low quality of the evidence identified. The clinical experience of favourable use and the seriousness of these patients, in many cases doomed to a potentially fatal outcome, led the DG to reach this agreement. If the TNF-α inhibitors fail, some case series seem to indicate that tocilizumab may be an alternative.77,78 In repeated DVT, immunosuppressive therapy is crucial to prevent relapses and reduce the risk of complications with post-thrombotic syndrome (symptoms and signs of chronic and disabling venous insufficiency).79 There is no consensus on the duration of TNF-α inhibitor treatment after achieving clinical remission in BS and relapses can occur at any time, which justifies close follow-up. It also seems prudent to prolong TNF-α inhibitor treatment, especially in patients with vascular and neurological manifestations.76 The DG, based on its clinical experience and low-quality studies has considered issuing a GCP recommendation in favour of the use of TNF-α inhibitors in cases with severe vascular involvement at the beginning, and another in favour of the use of tocilizumab as an alternative treatment when these are ineffective.

Anticoagulant treatment of thrombotic manifestations of BS remains controversial. The 2018 EULAR recommendations do not recommend anticoagulants to prevent DVT relapses, only in refractory cases and cerebral sinus thrombosis. After carrying out a SR in this regard and taking into account the opinion of a haematologist expert in coagulation, the DG agreed on long-term anticoagulation for patients with BS and recurrent venous thrombosis,80 while opting for antiaggregation for patients with thrombosis in arterial territories.81,82 Situations where we must add anticoagulant therapy to immunosuppressive treatment are DVT, Budd-Chiari, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and intracardiac thrombosis, always after screening for the risk of bleeding (rule out associated pulmonary aneurysms). The duration of anticoagulation is unclear; After an initial period of 3–6 months, the thrombotic and/or hemorrhagic risk must be weighed on an individual basis and take into account that BS can be considered a risk factor to prolong therapy indefinitely, at least while the disease is active. Reperfusion therapies (mechanical or pharmacological thrombolysis) in severe cases of thrombosis and reconstructive surgery or embolisation in arterial aneurysms may be necessary and should be performed, whenever possible, after the inflammation is controlled with immunosuppressants to reduce postoperative complications.83

Neurological-parenchymal manifestationsIn patients with refractory neurological-parenchymal phenotype of Behçet’s syndrome, what is the efficacy and safety of systemic pharmacological treatments?Nervous system involvement in Behçet's disease ranges between 5.3% and 10% of patients depending on the series,84 and is usually preceded by other forms of the disease. The central nervous system is the most frequent site of neurological involvement. The peripheral nervous system can also be affected, usually subclinically.85

Depending on the main location of the lesions in the central nervous system, 2 main patterns are distinguished: the parenchymal pattern and the vascular (non-parenchymal) pattern. The parenchymal type is more prevalent, appearing in 20%–60% of cases. It is characterised by small inflammatory lesions in the brain stem, hemispheres, basal ganglia, spinal cord, and meninges. These lesions can cause symptoms due to cortical involvement, pyramidalism or behavioural disorders.86 Sensitive symptoms, movement disorders and epilepsy have been described.87,88 Its acute onset is associated with a good response to treatment, but its chronicity can cause brain atrophy and predicts a more aggressive evolution.89 The spinal cord may also be affected, either due to contiguity of the lesions or in isolation, which constitutes a poor prognostic factor and the most common form of which is multifocal transverse mielitis.90 Treatment of neurological-parenchymal involvement in BS is a priority to avoid neurological and cognitive sequelae.

Recommendation 6: In patients with BS with refractory or recurrent neurological-parenchymal phenotype after conventional treatment, the use of TNF-α inhibitors is recommended, preferably adalimumab or infliximab (Strong recommendation in favour).

Recommendation 6.1: When TNF-α inhibitors are ineffective, the DG recommends the use of tocilizumab, despite the limited evidence available. Another possible therapeutic option is rituximab (GCP Recommendation).

Relevant clinical considerations:

- •

Implementation considerations

- -

In TNF-α inhibitor treatments, the DG considers that AEs are not very frequent, but they can be serious. However, they can be minimised with screening protocols for chronic infections and a vaccination programme for immunosuppressed patients:

- o

Prior to starting TNF-α inhibitor drugs, and by extension the rest of the biologics, it is very important to screen for tuberculosis with chest x-ray, tuberculin test and/or IGRA as appropriate, as well as lues serology, hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV.

- o

Previous vaccination for pneumococcus, hepatitis B, seasonal influenza and herpes zoster should be considered before starting treatment, without delaying its administration in severe cases.

- o

Before starting rituximab and during follow-up, immunoglobulin levels should be determined.

- o

- -

- •

Monitoring and assessment

- -

Periodic analyses must be performed and the possibility of optimising treatment should be subsequently assessed in case of achieving improvement or remission, as well as close monitoring of potential AEs, mainly infections.

- -

EULAR 2018 recommends TNF-α inhibitor drugs as the first line in severe disease or in refractory patients, without offering therapeutic alternatives. For our part, based on the limited evidence identified68,91–95 and on the clinical experience of the DG, TNF-α inhibitors are recommended in BS with refractory neurological-parenchymal phenotype, without being able to establish priority when choosing between them, since no studies have been identified that compare the use of different TNF-α inhibitors in the study population, although there are more data with adalimumab or infliximab. Differentially and after reviewing the existing literature, the use of tocilizumab as a second line is recommended.96–99 Rituximab is considered as the last therapeutic option, despite the few patients described in the literature and the various drug administration guidelines,100–103 which are not equivalent to those used in our healthcare context. Finally, the DG considers that the limited evidence available95 and the little experience in this group of patients with etanercept do not allow making a recommendation on its use.

The DG considers that since all the biological drugs described are not approved in the technical specifications for the health condition analysed and authorisation from the hospital management is necessary for their use, complications may arise at the time of their implementation, which may vary in each centre.

Gastrointestinal manifestationsIn patients with refractory gastrointestinal phenotype of Behçet’s syndrome, what is the efficacy and safety of systemic pharmacological treatments?The prevalence of GI manifestations in BS varies widely according to geographical distribution, ranging between 3% (Turkey, India) and 35%–50% (United Kingdom and Japan). From a pathogenic point of view, 2 types of involvement have been described: a vasculitis mainly of capillaries and venules that leads to the formation of ulcers due to inflammation of the digestive mucosa, and vasculitic involvement of the mesenteric arteries that causes intestinal ischaemia (intestinal angina or intestinal infarction).104 The most common complication is the appearance of single or multiple ulcers, typically volcano-shaped, which are usually located in the ileal or ileocecal region (although they have also been described in the oesophagus and colon). The patients present with abdominal pain and episodes of sometimes bloody diarrhoea, which can lead to acute or chronic complications (perforation, massive haemorrhage, obstruction and development of fistulas). They generally occur between 4.5 and 6 years after the appearance of oral ulcers.

The appearance of GI manifestations in BS is associated with a poorer prognosis, with a significant increase in morbidity and mortality. Between 33% and 62% of patients do not respond adequately to conventional treatment with systemic glucocorticoids, mesalazine and azathioprine (there is also limited experience with calcineurin inhibitors).105–107 Furthermore, among patients who respond to this first line of treatment, 25% relapse after 2 years, a percentage that increases to 43%–49% at 5 years.105–107

With conventional treatment, it is estimated that around one third of patients with GI involvement end up requiring surgery due to perforation, massive haemorrhage, obstruction, or development of fistulas.108–110 Hence the need to identify alternative treatments that are effective in refractory or recurrent cases.

Recommendation 7: In patients with BS with refractory or recurrent GI involvement after conventional treatment, the use of TNF-α inhibitory monoclonal antibodies is recommended, preferably adalimumab or infliximab (Strong recommendation in favour)

Recommendation 7.1: Its use will also be evaluated in patients with severe initial GI involvement who require rapid control of inflammation (GCP Recommendation).

Recommendation 7.2: In cases refractory to TNF-α inhibitors, evaluation of the use of tofacitinib is recommended, individualising the decision (GPC Recommendation).

Relevant clinical considerations

- •

In TNF-α inhibitor treatments, the DG considers that AEs are not very frequent, but they can be serious. However, they can be minimised with screening protocols for chronic infections and a vaccination programme for immunosuppressed patients:

- o

Prior to starting TNF-α inhibitor drugs, and by extension the rest of the biologics, it is very important to screen for tuberculosis with chest x-ray, tuberculin test and/or IGRA as appropriate, as well as lues serology and hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV.

- o

Previous vaccination for pneumococcus, hepatitis B, seasonal influenza and herpes zoster should be considered before starting treatment, without delaying its administration in severe cases.

- o

- •

Monitoring and assessment

- -

Periodic analyses should be performed and the possibility of optimising treatment should subsequently be assessed in the event of improvement or remission, as well as close monitoring of potential AEs, mainly infections.

- -

The EULAR 20187 recommendation and the 2020111 Japanese Society of Gastroenterology recommendation is for the use of TNF-α inhibitors in patients with refractory or recurrent GI involvement. The EULAR7 recommendations also contemplate its use as the first therapeutic step in serious initial cases that require rapid control of inflammation, since clinical and endoscopic improvement has been observed in a high percentage of cases. In the same sense, the DG has issued a strong recommendation in favour of its use in these patients, based on the evidence from a meta-analysis112 and several OS,113–115 and on their clinical experience. In those patients with a refractory or recurrent course despite treatment with TNF-α inhibitors (adalimumab or infliximab), the DG recommends the use of tofacitinib, always individualising the decision. Although the evidence is scarce, in the majority of cases with refractory or recurrent intestinal BS published to date, a favourable response is achieved, both clinical and endoscopic.116–118

In the opinion of the DG, it is foreseeable that rescue treatment in refractory cases will lead to substantial savings in resources by achieving better control of the disease activity, avoiding the development of complications and the need for surgery due to perforation, massive haemorrhage, obstruction or fistulas, and hospital admissions. Furthermore, biosimilars of infliximab and adalimumab are currently available at an acceptable economic cost. The DG considers that it is likely that the treatment of GI manifestations with TNF-α inhibitors (adalimumab and infliximab) will be generally accepted by patients and prescribers, since these are drugs with experience in their use in other diseases, with an acceptable safety profile and are generally used in patients with refractory and/or severe involvement who require rapid control of inflammation. In terms of feasibility, the indication for biological drugs (infliximab and adalimumab) and tofacitinib is outside the technical specifications. Since authorisation from the hospital management is necessary for its use, there may be obstacles when implementing these recommendations. The DG considers that the availability of recommendations such as these, endorsed by scientific societies, is an authoritative argument to justify the request.

DiscussionBS is a complex clinical situation that is characterised by the simultaneous or sequential presence of different clinical manifestations, with a chronic and relapsing-remitting course. It was initially described as a “trisymptomatic complex” due to the presence of the characteristic clinical triad of oral thrush, genital thrush and uveítis,119 but joint, vascular, neurological and/or GI manifestations may also appear.

There is a growing body of literature that supports that, within BS, different clusters of patients can be identified that include 4 predominant clinical phenotypes (mucocutaneous, articular, ocular and vascular), to which another 2 possible phenotypes can be added (neurological and GI).120

This major clinical diversity makes the therapeutic management of BS difficult. The therapeutic strategy could be adapted to the specific needs of the patient, depending on clinical phenotypes and their severity, since we frequently find cases of BS refractory to conventional therapies with isolated clinical manifestations or overlapping of different forms of involvement.

In 2018, the update of the 2008 EULAR recommendations for the management of patients with BS7 was published, based on data from a bibliographic review up to 2016, which is why they have become obsolete. Furthermore, these recommendations do not include the therapeutic attitude in cases of complex and refractory BS, nor do they propose lines of treatment, as proposed by Bettiol et al. in 2019, taking into account the different clinical phenotypes recently described.121

The absence of standardised and homogeneous recommendations for the treatment of patients with BS who do not respond to initial therapy has encouraged us to review the existing scientific evidence. This has been carried out by applying a strict and validated methodology for evaluating the quality of the evidence and establishing recommendations, in order to prepare an updated document with application in our healthcare field on how to treat these patients. Seven recommendations have been developed that include the management of 4 refractory or recurrent clinical phenotypes in BS: 1) mucocutaneous-articular; 2) vascular; 3) neurological-parenchymal, and 4) GI, and try to establish lines of therapeutic strategy.

Mucocutaneous involvement of BS is the most prevalent and can be observed in up to 75% of patients. Joint manifestations appear in 30%–50% of cases and arthritis can be associated with acneiform/papulopustular lesions and a higher frequency of enthesopathy, as previous studies have shown.120 Mucocutaneous and joint involvement significantly impacts the quality of life of patients with BS. Oral and/or genital aphthosis can frequently be recurrent and refractory to conventional therapy, with a significant increase in morbidity.

The EULAR 2018 recommendations propose a single recommendation for mucocutaneous symptoms and another for joint involvement, without specifying the management of refractory cases or prioritising the use of different drugs.7 Differentially, the SER recommendations focus on refractory BS cases.

Vascular manifestations are the main cause of morbidity and mortality in BS, especially in young men. BS can affect the entire vascular tree, veins and arteries, of all sizes. Arterial involvement is rare (3%–5%) and arterial aneurysms (pulmonary, visceral and peripheral) predominate.

The presence of recurrent superficial venous thrombosis and/or DVT in young men is characteristic. The thrombus adheres tightly to the inflamed wall of the vessel with a low probability of migrating, resulting in the development of pulmonary embolism being rare. The pathogenesis of thrombosis in BS is especially relevant to direct specific treatment, which is based on immunosuppression rather than anticoagulation, since vascular involvement is induced by an altered inflammatory response at the local vascular level that defines a natural model of thromboinflammation.122

Neurological involvement in BS marks the prognosis of the disease. The central nervous system is the most common site of neurological involvement, although the peripheral nervous system can also be affected. It has 2 forms of presentation: parenchymal in 3 out of 4 cases and neurological vascular. The parenchymal type is characterised by small inflammatory lesions in the brain stem, hemispheres, basal ganglia, spinal cord, and meninges. Depending on the location and form of onset, the clinical manifestations and prognosis can be very diverse. Treatment of neurological-parenchymal involvement in BS is a priority to avoid neurological and cognitive sequelae.

The appearance of GI manifestations in BS is associated with a poorer prognosis, with a significant increase in morbidity and mortality. The main symptom is abdominal pain and the most common complication is the appearance of single or multiple intestinal ulcers predominantly in the ileocecal area. Between 33% and 62% of patients do not respond adequately to conventional treatment with systemic glucocorticoids, mesalazine and azathioprine.105–107 Relapses are frequent and, with conventional treatment, it is estimated that around a third of patients with GI involvement eventually require surgery due to perforation, massive haemorrhaging, obstruction or development of fistulass.108–110 Hence the need to identify alternative treatments that are effective in refractory or recurrent cases.

The main limitation of these recommendations is the scarcity of evidence available on the management of refractory BS and the lack of quality RCTs, especially in manifestations that imply greater mortality, such as vascular, neurological or GI manifestations. Another limitation that has prevented greater precision is the absence of a clear definition in the literature of “difficult to treat” or “refractory” BS, as well as the difficulty in interpreting results of the selected studies as there are no universally accepted or agreed upon cut-off points for the indices used, which prevents the concepts of low activity, high activity or refractoriness from being adequately defined.123 Furthermore, the SR of the literature has revealed great variability in the studies analysed. For all these reasons, a significant part of the recommendations issued are based mainly on the experience and criteria of the DG.

Treatment algorithms for each refractory clinical phenotype of BS are proposed in Appendix A Annex III of the supplementary material. These algorithms are based on the current available evidence and, like the recommendations, should be considered as an aid to the decision-making of clinicians directly involved in the care of these patients. The DG wants to highlight that in no case should algorithms and recommendations be considered as restrictive or mandatory rules of use, but rather as recommendations for action.

ConclusionsThe treatment of the most severe or refractory clinical manifestations of BS is a particularly difficult and complex clinical scenario, where the limited scientific evidence published is not solid, and there are no recommendations agreed upon by scientific societies to date. In order to respond to this need, we present the first multidisciplinary document of specific SER recommendations for the therapeutic approach of these patients in the most frequent scenarios in clinical practice.

The DG members who drafted these recommendations have extensive experience in the use of the different therapies contemplated in this document, as well as in other complex rheumatological diseases, and extrapolated their experience to issue these recommendations in refractory BS, always assessing the risk/benefit. The importance of these recommendations lies in the effort of a multidisciplinary group to establish the best therapeutic strategy for patients with BS that is difficult to manage, in order to reinforce the decisions of the clinicians involved and homogenise care and applicability in our healthcare setting.

Research agendaThis document of recommendations is based on an SR of the literature, which has helped the authors locate areas of scientific evidence where the DG considers that a research effort should be made in the future. Among others, the following can be mentioned:

- •

The DG considers it essential to study the effectiveness of different biological drugs in the treatment of different BS disorders, for which it would be necessary to carry out comparative clinical trials between drugs that evaluate different patient populations.

- •

Real-life population studies with prolonged follow-up are necessary to determine the doses and duration of biological therapies and anticoagulation, and the results in efficacy and safety in these patients.

- •

Widely agreed definitions of remission, minimal activity and persistence are necessary.

- •

Widely agreed definitions of therapeutic response, complete, partial and refractoriness are necessary.

- •

Greater knowledge is needed about risk factors for the development of severe manifestations refractory to conventional treatment, in order to identify these patients and avoid delaying the start of the therapies recommended in these cases.

- •

The DG considers it necessary to carry out a controlled study to support the effectiveness of anti-TNFα in the treatment of different manifestations. Meanwhile, it is advisable to promote the development of a national registry on the use of biologic in the BS.

The authors have made substantial contributions regarding: a) the conception and design of the study and the data analysis; the draft of the article or the critical review of the intellectual content, and the final approval of the version presented, and b) the review of the evidence and the preparation of the systematic review report.

FundingSpanish Foundation of Rheumatology.

Conflict of interestsJenaro Graña Gil has received funding from Lilly, Pfizer, Roche, Novartis, Amgen, Abbvie and Janssen for attendance at courses/conferences and fees for presentations, for the financing of educational programmes or participation in research by Lilly and Amgen, and as a consultancy by Janssen.

Clara Moriano Morales has received funding from Lilly, Pfizer, Roche, Theramex, Stada and Boehringer Ingelheim for attendance at courses/conferences, fees for presentations or consultancy from GSK, AstraZeneca, Lilly, Amgen and Grünenthal, and research funding from Roche.

José Luis Martín Varillas has received funding from Lilly, Pfizer, Janssen, Nordic and UCB Pharma for attendance at courses/conferences and fees for presentations.

Vanesa Calvo del Río has received funding from Lilly, Pfizer, MSD, Abbvie, UCB Pharma, Grünenthal and Celgene for attendance at courses/conferences and speaking fees.

Patricia Moya Alvarado has received funding from Pfizer, Roche and Novartis for attendance at courses/conferences, fees for presentations and for the financing of educational programmes or courses.

Francisco Javier Narváez García has received funding from Roche, Bristol, Lilly, Abbvie, Pfizer, Boehringer, Sanofi, GSK, Gebro Pharma, Kern and Sobi for attendance at courses/conferences or fees for presentations, as well as for consultancy.

Gerard Espinosa has received speaking fees from GSK, Boehringer, Otsuka and Gebro, from GSK for research funding, and from Otsuka, AstraZeneca and GSK for consulting.

Noé Brito García, José Mateo Arranz, Petra Díaz del Campo Fontecha, Mercedes Guerra Rodríguez and Manuela López Gómez have declared the absence of a conflict of interest.

Félix Manuel Francisco Hernández, Raquel Dos Santos Sobrín, Jesús Maese Manzano, Julio Suárez Cuba, Mar Trujillo Martín and Juan Ignacio Martín Sánchez present an absence of interest in relation to their work in this document of recommendations.

The group preparing this work would like to express its gratitude to Dr. Belén Atienza Mateo and Dr. Sergio Martínez Yélamos, expert reviewers of the document, for their critical review and contributions to it. They would also like to thank Dr. Federico Díaz González, director of the SER Research Unit, for his participation in the review of the final manuscript and for contributing to preserving the independence of this document.