We describe the case of a 51-year-old woman with a seropositive, erosive, and non-nodular rheumatoid arthritis of 15 years of evolution. The patient had poor compliance with medical visits and treatment. She came to the clinic with persistent pancytopenia and spleen and liver enlargement. Liver and bone marrow biopsies were carried out and amyloidosis, neoplasias and infections were ruled out.

We discuss the differential diagnosis of pancytopenia and spleen and liver enlargement in a long-standing rheumatoid arthritis patient.

Se describe a una paciente de 51 años de edad con artritis reumatoide de 15 años de evolución, seropositiva –factor reumatoide positivo y anticuerpos antipéptido citrulinado positivos–, erosiva, no nodular, con poca adherencia al tratamiento y controles médicos, que presentó un cuadro caracterizado por pancitopenia persistente y hepatoesplenomegalia. La biopsia hepática y de médula ósea descartó tumores, amiloidosis e infecciones.

Se discute el diagnóstico diferencial de pancitopenia y hepatoesplenomegalia en una paciente con artritis reumatoide de larga evolución.

The patient is a 51-year-old female diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who met the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology 1987, with disease onset 15 years prior, seropositive (rheumatoid factor [RF] and anti-peptide antibodies citrullinated), erosive disease, non-nodular, who had a family history of lymphoma. She denied substance abuse and toxic tobacco or alcohol use. This patient had been under treatment with leflunomide (6 years), methotrexate (3 years) and hydroxychloroquine (1 year) without response, for which she received 2 months of treatment with etanercept, which was suspended due to a skin reaction. She later received adalimumab during 5 months in 2010, lost to follow-up.

In September 2012 she complained of fatigue, loss of 8kg of weight in 4 months, grade III dyspnea and abdominal distention for 10 days. On physical examination the patient had no fever (37°C), was normotensive (blood pressure 110/80mmHg), presented tachycardia (110bpm), tachypnea (28cycles/min), thin skin and pale mucous membranes with multiple bruises. The remainder of the examination showed the presence of a pulmonary systolic multifocal murmur 2/6, bibasal hypoventilation and dullness, globular abdomen with hepatomegaly and splenomegaly, ascites and collateral circulation, and a painful ulcer, 5cm in diameter on the trochanter of the right hip, and purpura on the legs below the knees. There was hypotrophy of interosseous muscles, ulnar deviation, swan neck deformity and arthritis of the metacarpophalangeal joints of the third right and fourth bilateral fingers. The clinimetry showed HAQ: 2375 and DAS28: 7.29 (ESR: 142mm in the first hour, 3 swollen joints, 12 tender joints, patient assessment of activity: 100mm).

Laboratory data showed: hematocrit 25%, hemoglobin 7.6g/dl, WBC 1900cells/ml, neutrophils 1140cells/ml, platelets 82 000cells/ml, CRP 17.4mg/l, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 142mm in the first hour, increased alkaline phosphatase (997U/l), RF (latex: 1/1280), anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (53.7U/ml) and anti-nuclear antibodies (Hep2): 1/2560. Renal function, alanine aminotransferase (13U/l), aspartate aminotransferase (19U/l), anticardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, anti-DNA (Crithidia), C3 and C4, and serology for histoplasmosis, HBV and HCV were normal.

Cultures of blood, urine, stool and bone marrow were negative for common bacteria, typical and atypical mycobacteria and fungi. Thoracentesis reported an uncomplicated exudate. Computed tomography with contrast (oral and IV) of the head, neck and pelvis were normal; the scan showed the presence of a bibasal pleural effusion, and the abdomen (Fig. 1) showed homogeneous hepatomegaly (230mm of longitudinal diameter) and splenomegaly (200mm of longitudinal diameter). Hepatic vessels on an eco Doppler ultrasound showed dilation of the portal vein (14mm in diameter) with no evidence of thrombosis. Upper gastrointestinal fiberoptic endoscopy ruled out the presence of esophageal varices.

The peripheral blood smear showed leukopenia and thrombocytopenia, so a bone marrow biopsy was performed, finding hypercellularity with megakaryocytes, myeloid hyperplasia and isolated clusters of mature lymphocytes. The patient began treatment with methylprednisolone 50mg/day orally for 1 month, with subsequent gradual decline, methotrexate 15mg/week, calcium, vitamin D and folic acid. However, despite the immunosuppressive therapy, pancytopenia persisted (hematocrit 28.4%, hemoglobin 9.2g/dl, WBC 3200cells/ml, platelets 44 000cells/ml) and the patient showed worsened liver function (alanine aminotransferase: 62U/l; aspartate aminotransferase: 47U/l), leading to a liver biopsy.

Based on the results it was decided to treat the patient with prednisone 10mg/day, methotrexate 10mg/week, leflunomide 20mg/day, folic acid, calcium and vitamin D, presenting inactive RA with pancytopenia, but no neutropenia or bleeding.

Differential DiagnosisFaced with a patient diagnosed with longstanding RA who develops persistent pancytopenia and hepatosplenomegaly, the first step in diagnostic reasoning should be to ask whether it is due to concomitant conditions, treatment, or if it is secondary to the underlying disease.

InfectionsPatients with RA have an increased risk of infection.1 The major risk factors for their development is the presence of extra-articular manifestations, comorbidities, advanced age, leukopenia, and therapy with corticosteroids and biologics, among others.2 The most common infections are the upper respiratory tract, skin and soft tissue, bones and joints.3

Concern about the risk of severe opportunistic infections (histoplasmosis, tuberculosis, leishmaniasis, Pneumocystis carinii) among patients with rheumatic diseases has increased, especially since they share several clinical features such as fever, fatigue, chest pain, pleural effusion, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates, pericarditis, myalgia, epistaxis, joint pain, arthritis, erythema nodosum, diffuse papules, lesions in the oropharynx, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, stroke, seizures, endocarditis, anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin, and uveitis.

Occasionally, histoplasmosis is first manifested by extrapulmonary organ involvement. These isolated lesions are usually considered manifestations of disseminated disease, despite the lack of lung involvement. This situation may mimic other diseases, such as Felty's syndrome, and it is important to suspect it as an unusual manifestation of the disease when it occurs4,5 in an outpatient setting.

Therefore, although our patient came from an endemic area (the Argentine coast) and histoplasmosis may mimic a flare of RA or an extra-articular manifestation of it (Felty's syndrome: fatigue, joint pain, arthritis, pleural effusion, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia and abnormal liver function), serology, blood, bone marrow and liver cultures were negative for histoplasmosis and deep mycoses, allowing us to rule out this diagnosis.

NeoplasmsRA is characterized by persistent immune stimulation, which could lead to polyclonal lymphocytic proliferation, increasing the potential for malignant transformation.6 According to some reports, the risk of cancer is two times higher in RA patients compared with the general population, with the estimated risk in these patients for developing lymphoma7 ranging from 1.5 to 8.7, while the relative risk of developing non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in Felty's syndrome is closest to 13.8 Anti-TNF drugs do not seem to increase the incidence of lymphoma.9 Current disease in this case includes a series of hematological symptoms (weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly, leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia) that made us suspect lymphoma. However, the absence of lymphadenopathy confirmed by a CT scan and negative results on bone marrow and liver biopsy allowed us to exclude them.

AmyloidosisAnother rare disease with a poor prognosis associated with longstanding RA patients who present with systemic symptoms, hepatomegaly, cardiomyopathy, neuropathy, purpura and proteinuria, is amyloidosis.

It is characterized by the extracellular accumulation of amorphous, eosinophilic hyaline material.10 The diagnosis is established by Congo Red staining of rectal mucosa, abdominal fat, and tissues involved.11 In this patient, no such amorphous material was found in the liver tissue.

Felty's SyndromeIt occurs in <1% of RA (10–15 years since disease onset) with positive RF and severe joint disease (erosions, dislocations) contrasting with absent or moderate joint inflammation and accompanied by extra-articular manifestations (weight loss, brown pigmentation on the pretibial area, ulcers on the lower limbs, subcutaneous nodules, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly as well as Sjögren syndrome).

60%–70% occurs in women 50–70 years of age, and is characterized by the triad of RA, persistent neutropenia (<2000/mm3) and no other reason that explains it, and splenomegaly, with a strong association with HLA-DR4 (nearly 95% of cases).12–15

The clinician should consider this diagnosis as likely given the time since disease onset (15) and the characteristics of the disease (positive RF, erosions), and neutropenia and splenomegaly accompanied with weight loss, pigmented lesions and leg ulcers.

Pseudo-Felty SyndromeThe proliferation of large granular lymphocytes, also called pseudo-Felty's syndrome, is a rare systemic complications (<0.6%) of RA. It is characterized by the presence of persistent neutropenia, lymphocytosis and splenomegaly, which in the absence of proper treatment can progress in 3%–14% of cases to large granular lymphocyte leukemia.

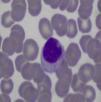

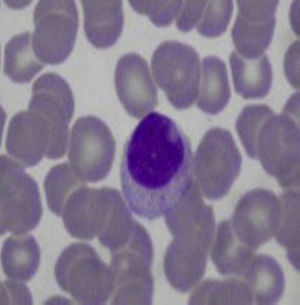

Approximately 30%–40% of patients with Felty's syndrome presents an expansion of large granular lymphocytes in peripheral blood (lymphocytosis >0.5×109/l) (Table 1).12,13,16,17 This accounts for 5%–10% of circulating mononuclear cells which morphologically are large (15–18μ in diameter), round or have an indented nucleus and abundant cytoplasm with azurophilic granules (Fig. 2).18 When associated with clonal invasion of the bone marrow, spleen or liver, it is called large granular lymphocyte leukemia. This is a low-grade malignancy, which is accompanied by neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia and high susceptibility to infection.19 The patient in this case had long-standing RA with severe joint damage and serious sequelae, along with clinical manifestations similar to Felty's syndrome, but without lymphocytosis or large granular lymphocytes in the peripheral blood smear, so this diagnosis was also discarded.

Clinical and Laboratory Differences Between Felty's Syndrome and Pseudo-Felty.

| Felty's syndrome | Pseudo-Felty syndrome | |

|---|---|---|

| Extra-articular manifestations | Common | Common |

| Erosive arthritis | Common | Common |

| Recurrent infections | Common | Common |

| Splenomegaly | Common | Common |

| Leukemia progression | Rare | 3%–14% |

| Spontaneous remission | 0%–22% | 0%–14% |

| WBC | Low | Normal/low |

| Lymphocytosis | Absent | Present |

| RF, ANA (positive) | Common | Common |

| Response to splenectomy | Improvement | Exacerbation |

ANA, antinuclear antibodies; RF: rheumatoid factor.

The presence of significant liver disease in patients with RA is rare. When a significant liver disease occurs, it is usually due to autoimmune systemic involvement which also compromises the liver, or coinfection with hepatotropic viruses such as Hepatitis B and C viruses, or treatment-associated hepatotoxicity.20

Hepatic nodular regenerative hyperplasia (HNRH) is a rare disorder first described in 1953 by Ranstrom as “miliary hepatocellular adenomatosis” and has many synonyms, including non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, diffuse nodular hyperplasia and nodular transformation of the liver.21 Steiner Coind called it nodular regenerative hyperplasia, the currently accepted term for this lesion, characterized by secondary liver nodules, hepatocyte hyperplasia with absent or low fibrosis and portal hypertension. The prognosis is generally good, unlike portal hypertension due to cirrhosis. Both are easily confused, so it is essential to perform a liver biopsy.22

Clinical Diagnosis of the PresenterOur patient had the clinical features of RA associated with Felty's syndrome.

Integrating this data with Doppler ultrasound of hepatic vessels, which showed dilatation of the portal vein with signs of portal hypertension (ascites and peripheral pancytopenia secondary to splenomegaly), and having ruled out other causes of hepatosplenomegaly, we assumed that the patient had HNRH as an autoimmune condition secondary to the underlying disease, making a liver biopsy the necessary diagnostic test to confirm the diagnosis.

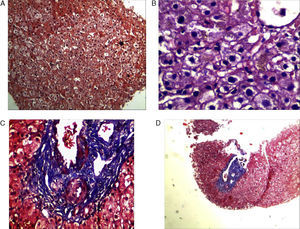

Final Result and CommentThe liver biopsy was a diagnostic test, demonstrating the presence of parenchymal nodularity and hepatocyte regeneration with preserved portal tracts without evidence of significant fibrosis and negative Congo red staining (Fig. 3).

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia is a rare condition that affects both sexes and is usually found in association with many diseases (Table 2), with RA and Felty's syndrome the most frequent.21,23,24 HNRH patients may be asymptomatic or present with recurrent abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, signs of hypersplenism (splenomegaly or hematologic abnormalities) and signs of portal hypertension (such as ascites, bleeding of esophageal varices, or splenomegaly). Laboratory tests show mild abnormal liver function tests in a nonspecific manner (mainly elevated aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, GGT and alkaline phosphatase).

Conditions Associated With Nodular Hepatic Regenerative Hyperplasia.

| Rheumatic | Hematologic | Pharmacological | Congenital | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | ITP | Azathioprine | Congenital absence of portal vein | Toxic oil syndrome |

| Felty's syndrome | Polycythemia vera | Busulfan | Cardiac abnormalities | Metastasis |

| SLE | Essential thrombocytosis | Doxorubicin | PBC | |

| PAN | Sickle cell | Cyclophosphamide | Celiac disease | |

| Systemic sclerosis | Macroglobulinemia | Chlorambucil | CHF | |

| APS | Myeloid metaplasia | Bleomycin | TBC | |

| CREST syndrome | Lymphocytic Leukemia | |||

| POEMS Syndrome | Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

RA: rheumatoid arthritis; PBC: primary biliary cirrhosis; CHF: congestive heart failure; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; PAN: polyarteritis nodosa; POEMS: polyneuropathy, organomegaly, M protein, organomegaly, skin disorders; ITP: idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; APS: antiphospholipid syndrome; TB: tuberculosis.

68% of patients have positive antinuclear antibodies and a similar percentage of patients are positive for RF. With regard to the pathogenesis, several hypotheses have been proposed: (a) increase of portal blood flow due to an increase in splenic flow; (b) primary vascular injury, for example, RA-associated vasculitis, and (c) altered hepatic blood flow due to hepatic ischemia.

In 1998, Perez Ruiz et al. showed a possible role of antiphospholipid antibodies in its pathogenesis.24

On the other hand, normal findings on needle biopsy do not exclude the diagnosis because, although HNRH diffusely involves the liver, it does so in patches and the degree of nodularity may vary from one part of the liver to another. Treatment focuses on correcting the underlying cause (autoimmune disease, hematologic disorders, drugs).

Although these patients have a relatively benign prognosis compared with cirrhotic portal hypertension, a number of patients require splenectomy and referral to address complications such as pancytopenia and gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to esophageal varices. Liver transplantation is rarely required and is reserved for patients with hepatic impairment.25,26

In conclusion, HNRH is a complication that can occur during the development of autoimmune diseases, which should be considered in cases with hepatomegaly, persistent abnormalities of liver function tests and/or signs of portal hypertension.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare this research did not perform experiments on humans or animals.

Data confidentialityThe authors state that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Conflict of InterestThe authors have no conflict of interest to state.

Please cite this article as: Bedoya ME, Ceccato F, Paira S. Hepatomegalia y esplenomegalia en una paciente con artritis reumatoide. Reumatol Clin. 2015;11:227–231.