To develop updated guidelines for the pharmacological management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

MethodsA group of experts representative of different geographical regions and various medical services catering to the Mexican population with RA was formed. Questions based on Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) were developed, deemed clinically relevant. These questions were answered based on the results of a recent systematic literature review (SLR), and the evidence's validity was assessed using the GRADE system, considered a standard for these purposes. Subsequently, the expert group reached consensus on the direction and strength of recommendations through a multi-stage voting process.

ResultsThe updated guidelines for RA treatment stratify various therapeutic options, including different classes of DMARDs (conventional, biologicals, and JAK inhibitors), as well as NSAIDs, glucocorticoids, and analgesics. By consensus, it establishes the use of these in different subpopulations of interest among RA patients and addresses aspects related to vaccination, COVID-19, surgery, pregnancy and lactation, and others.

ConclusionsThis update of the Mexican guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of RA provides reference points for evidence-based decision-making, recommending patient participation in joint decision-making to achieve the greatest benefit for our patients. It also establishes recommendations for managing a variety of relevant conditions affecting our patients

Desarrollar guías actualizadas para el manejo farmacológico de la artritis reumatoide (AR).

MétodosSe conformó un grupo de expertos que fueran representativos de las distintas regiones geográficas y los diferentes servicios médicos que atienden a la población mexicana con A. Se desarrollaron preguntas basadas en Población, Intervención, Comparación y Desenlace [Outcome] (PICO) que fueron consideradas relevantes desde el punto de vista clínico; las preguntas encontraron su respuesta en los resultados de una revisión sistemática de la literatura (RSL) reciente y la validez de la evidencia fue evaluada mediante el sistema GRADE, considerado un estándar para estos fines. Posteriormente el grupo de expertos desarrollaró acuerdo en la dirección y fuerza de las recomendaciones mediante un proceso de votación en distintas etapas.

ResultadosLas guías actualizadas para el tratamiento de AR y categorizan en forma estratificada a las distintas opciones terapéuticas incluyendo las distintas familias de FARME (convencionales, biológicos e inhibidores de JAK), además de AINE, glucocorticoides y analgésicos. Establece por consenso el uso de todos ellos en distintas subpoblaciones de interés de pacientes con AR y aborda además aspectos relacionados con vacunación, COVID-19, cirugía, embarazo y lactancia y otros.

ConclusionesLa presente actualización de las guías mexicanas para el tratamiento farmacológico de la AR brinda elementos de referencia en la toma de decisiones basados en la evidencia científica más reciente y recomienda la participación del paciente para la toma de decisiones conjuntas en la búsqueda del mayor beneficio de nuestros pacientes; establece además recomendaciones para el manejo de una diversidad de condiciones relevantes que afectan a nuestros pacientes.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic inflammatory disease that affects the synovial joints. It is a chronic, progressive disease in which the inflammatory process eventually causes joint destruction and disability. Its natural course is marked by the progressive worsening of this joint and systemic inflammation. Fortunately, this can be modified by the use of specific treatments, which should be periodically reassessed and restructured, based on the outcome obtained. If the treatment fails to induce remission, or failing that, low disease activity, the patient's prognosis is significantly poorer, not only at the joint level, but also at the systemic level, compromising the cardiovascular, pulmonary and metabolic bone functions, among others.1 RA is a prevalent disease in Mexico, affecting more than 2% of the population in some of the country’s regions.

The treat-to-target strategy in RA is a strategy involving assessment and therapeutic restructuring cycles, based on objective indicators of disease activity, and its goal is to bring patients to a state of disease remission or, failing that, low activity by optimising their treatment. RA treatment constantly evolves, incorporating new knowledge on the efficacy and safety of specific drugs, in addition to implementing new agents.

Since the formulation of the latest Mexican guidelines, new evidence has been generated regarding the efficacy and safety of the different therapeutic alternatives for patients with RA, and we therefore considered it appropriate to review the guidelines, incorporating recent evidence. Our purpose here was to obtain greater benefit for our patients, and to facilitate evidence-based decision-making for the rheumatologist and other health professionals involved in the RA patient management.

Treatments have been divided into defined subgroups, and given the nature of our times, we have included specific sections for COVID-19, vaccination, and other topics of interest.

RationaleGlobal prevalence of RA oscillates around 1% in the adult population. However, this prevalence is higher in some regions of Mexico, such as Yucatán, where it is greater than 2%. It predominantly affects women in their 50’s, and it has been described that the age of onset in Mexican patients is up to 10 years younger compared to European Caucasian populations.1 This earlier onset is a factor that impoverishes the prognosis of our patients.

RA is a polyarticular, symmetrical, potentially progressive, debilitating and disabling disease, which can shorten survival from 3 to 18 years during its evolution. It is therefore vital to achieve disease remission or at least low disease activity from its earliest stages, and, as far as possible, prevent the systemic complications of extra-articular inflammation, including cardiovascular disease, which is the main cause of death. The failure of initial treatment strategies establishes the need to escalate treatment sequentially and on occasion consider the diagnosis of difficult-to-treat RA.2,3

Cardiovascular involvement, which sometimes presents as major cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, sudden death, heart failure, pulmonary thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, and cerebral vascular disease),4 is the main cause of mortality, followed by interstitial lung disease.5

Another problem derived from both RA activity and treatment with ≥5 mg/d prednisone or equivalent, is osteoporosis, which occurs in 30% of patients.6 Other extra-articular manifestations may also occur, including sleep disturbances, asthenia, etc.7,8

MethodologyGeneral objective: to formulate scientific evidence-based recommendations on the pharmacological treatment of patients with RA to improve their quality of life and reduce disease-associated complications. Clinical aspects included: treatment and special populations. Clinical aspects not included: detection, prevention, diagnosis and rehabilitation. Target users: rheumatologists. Conflict of interest declaration: the members of the guideline development group reported the presence or absence of potential conflicts of interest. Information was collected using a standardised format. The guideline development group (GDG) was convened by the Mexican College of Rheumatology (MCR), which brought together rheumatology specialists who had extensive experience in the treatment of RA. Clinical questions were formulated in PICO format, and the analysis of the evidence and preparation of recommendations were coordinated by experts in the methodology of developing Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) and in evidence-based medicine (EBM). In addition, a librarian helped to develop the algorithms for the systematic search of evidence. Once the clinical questions had been formulated, the inclusion criteria were defined to structure the search strategy from the date of the last guideline update and publication (2019). The databases of Pubmed (R: 497), Embase (R: 519) and The Cochrane Library (R: 4) were consulted. Furthermore, a search was carried out in the LILACS Latin American database, for which the regional BVS portal was used, obtaining 13 results. The main descriptors (Medical Subject Headings [MeSH]), but not the only ones, used for the systematic search of evidence were: rheumatoid arthritis, treatment, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, anti interleukin-6 (anti-IL6, tocilizumab, sarilumab, sirukumab), abatacept, monoclonal anti-B cell antibody, rituximab, protein kinase inhibitors or janus kinase inhibitors or JAK inhibitors, baricitinib, upadacitinib, filgotinib, tofacitinib, biosimilar disease modifying antirheumatic drugs, glucocorticoids y nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In total, the searches yielded a universe of 532 unique documents of which we selected 161. Literature review: 2 members of the guideline development group selected potentially useful documents by title and abstract. Useful publications were identified for full text review. In the event of any lack of agreement between the 2 evaluators, a third party was involved to reach an agreement. The GRADE system was used to classify evidence reliability. The data extracted from this review were placed in the evidence tables prepared using the GRADEprofiler software. Formulation of recommendations: To formulate recommendations, the data contained in the evidence tables were used, together with the clinical experience of the GDG. For each recommendation, a structured consensus was reached in which clinical experts and methodologists participated. In cases where there was no evidence or it was insufficient, a consensus was reached that included all those involved in the GDG to generate a recommendation. The Delphi method was used to create consensus.

General principles of rheumatoid arthritis treatment- •

Reach the diagnosis in the initial phases.

- •

Begin treatment as soon as possible to onset of clinical symptoms.

- •

Individualise treatment.

- •

The rheumatologist is responsible for directing the pharmacological treatment of patients with RA. Early patient referral is therefore extremely important.

- •

Treat RA by joint agreement between the patient and the clinician.

- •

When initiating or modifying pharmacological treatment for RA, consider personal aspects of the patient, including comorbidities.

- •

Pharmacological treatment for RA aims at remission or, failing that, low disease activity.

- •

Consider therapeutic alternatives, based on the availability and accessibility of the patient’s context.

- •

Monitor adverse effects (AE) related to the safety profile and mechanism of action of each drug, especially biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) or protein-kinase/janus kinase inhibitors (JAK).

- •

The use of bDMARDS or JAK inhibitors is not recommended in patients with active infection.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are part of the treatment of RA symptoms. They are all useful, depending on the characteristics of each patient. Celecoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor, is associated with a lower overall mortality rate from cardiovascular causes, both when compared with other NSAIDs and with placebo.9 Likewise, its use has been related to a lower increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels and a lower incidence of high blood pressure, compared to other NSAIDs.10 Etoricoxib shows greater gastrointestinal safety when compared to other non-selective NSAIDs11 in patients with RA.

The use of low-dose glucocorticoids (GC) (equivalent to 10 mg or less of prednisone) in patients with RA has been associated with a decrease in lumbar and femoral bone mineral density, with a higher prevalence (13%) of vertebral fractures, compared to patients who did not use them.12 However, the use of 5 mg of prednisone as maintenance for 24 weeks in patients who had achieved remission or low activity with tocilizumab was associated with lower activity indices, measured with DAS-28, and a lower risk of reactivation after this maintenance treatment.13 Likewise, it was associated with better long-term quality of life, although with a higher frequency of AEs.14 Significantly, even in patients without poor prognosis markers who used GC in the initial COBRA-slim treatment scheme, it was determined that they maintained lower disease activity, even after 16 weeks of suspending them.15 Furthermore, after its administration, the patients who received GC with this scheme consumed fewer NSAIDs, had less need for analgesics,16 and less spontaneous pain.17 Notwithstanding, this benefit does not appear to be observed with other treatment regimens.18

Certainty of the evidence: Low ○○⊗⊗

RecommendationsConsideration of NSAIDs in disease symptom control is recommended.

Conditional recommendation

Non-combination of NSAIDs is recommended.

Strong recommendation

Individualised use of ≤10 mg/day prednisone or equivalent is suggested as a "bridging" therapy with conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) or when disease control with csDMARDs fails in patients diagnosed with AR. Use the lowest dose for the shortest time possible.

Conditional recommendation

Individualised use of low doses of GC (≤10 mg/day prednisone or equivalent) in early RA (less than 6 months of evolution) with poor prognostic factors (seropositivity, high clinical activity, erosions) is suggested, to reduce clinical activity and radiographic progression. Use the lowest dose for the shortest time possible.

Conditional recommendation

Individualised use of high doses of intravenous GC (methylprednisolone pulses) is suggested in patients with severe extra-articular manifestations (mononeuritis multiplex, rheumatoid vasculitis).

Strong recommendation

Conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugsMethotrexate (MTX)MTX continues to be the cornerstone of RA management. It is recommended as initial treatment in patients with active RA, either as monotherapy or in combination with GC, csDMARDs or bDMARDs.19 Starting at a high dose (greater than 15 mg/week) is not recommended, since, although it was associated with a lower DAS, it was not related to a lower score on the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ). In addition to the benefit of MTX on disease activity, there is a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events. In general, the use of MTX is well accepted among patients, with slight preferences for parenteral treatment (subcutaneous or intramuscular) over the oral route.20 Patients are aware of the treatment benefits over side effects, whether serious or non-serious. The presence of a high body mass index (BMI), positive rheumatoid factor (RF) and a high HAQ score increases the risk of discontinuing treatment due to AEs, with gastrointestinal disorders being the most frequent.21 Negative anti-citullinated protein antibodies (ACPA), smoking and high creatinine levels are associated with the risk of transaminasitis, for which monitoring through liver function tests is important. Due to the risk of haematological toxicity, it is important to perform blood biometry. In order to reduce secondary MTX AEs the use of folic acid is recommended.22

Certainty of the evidence: Moderate ⊗⊗⊗○

RecommendationsThe use of csDMARDs as soon as possible is recommended.

Strong recommendation.

The use of MTX in monotherapy is recommended as initial treatment in patients with active RA (initiate treatment with oral MTX due to the ease of administration. If >15 mg/week doses are required, parenteral MTX should be considered) If response to MTX monotherapy is inadequate or there is active disease with poor prognostic factors, its use in combination with other csDMARDs or bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors is recommended.

Strong recommendation.

The use of csDMARD monotherapy is recommended in patients with active RA without prior exposure to DMARDs.

Strong recommendation.

The use of triple therapy with csDMARDs or combined therapy with MTX and bDMARDs is suggested in patients with RA who do not respond to csDMARDs alone.

Conditional recommendation

Leflunomide (LEF)Baes et al., reported that LEF at a dose of 20 mg/day had the greatest probability of being the best treatment, based on the number of treatment abandonments due to lack of efficacy,23 and in a comparison of LEF with tacrolimus, a difference in DAS 28 means of –.18 (95% CI: –6.81−.44) at 28 weeks was reported.24 The addition of LEF to MTX is better than MTX as monotherapy to improve activity, function and quality of life in the short/medium term. In a systematic review, which evaluated the efficacy of LEF as monotherapy vs. MTX at 52 weeks (OR: .88; 95% CI: .74–1.06) for ACR20, a trend was observed in favour of MTX, with a mean difference (MD) in the number of swollen joints of –.82 (95% CI: .24–1.39) and .27 (95% CI: −.4−.94) in the number of painful joints. LEF was associated with a greater increase in liver enzymes when compared to MTX, with an OR: .38 (95% CI: .27–.3). However, it was associated with less gastrointestinal discomfort (OR: 1 .44; 95% CI: 1.17–1.79). With respect to non-serious infections, their results were very similar.25 In a study based on treat-to-target objectives for the addition of a second csDMARD to patients already receiving MTX, no change was observed when combining with HCQ or sulfasalazine, unlike the combination with LEF with which there was improvement in disease activity without increased frequency of AE.26

Certainty of the evidence: Moderate ⊗⊗⊗○

RecommendationsThe use of LEF as monotherapy is recommended as initial treatment in patients with active RA. When response to monotherapy is inadequate, its use in combination with other csDMARDs, b-DMARDs or JAK inhibitors is suggested.

Strong recommendation.

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)In 2 systematic reviews and a meta-analysis that compared HCQ as monotherapy or in combination with MTX, sulfasalazine (SSZ) and/or LEF, the efficacy of HCQ against SSZ was very similar, over a 6-month period, for erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), morning stiffness, number of swollen joints, joint pain, patient assessment, and physician global assessment; At 2 years, the combination of MTX + SSZ + HCQ triple therapy was associated with a higher percentage of ACR20 and ACR50 responses than with MTX + SSZ (78 vs. 49%; p: .02 and 55 vs. 29%; p: .005, respectively).26–28 The adverse effect most associated with the use of HCQ was skin hyperpigmentation (OR: 4.64; 95% CI: 1.13–19.00). Other adverse effects included headache, dizziness, fatigue, gastrointestinal manifestations and dermatoses, in addition to the most feared AE of maculopathy, which is why periodic ophthalmological evaluation is recommended. Its use may be considered in patients with RA and metabolic comorbidities due to its beneficial effects on total cholesterol, LDL and triglyceride levels.29

Certainty of the evidence: Moderate ⊗⊗⊗○

RecommendationsThe use of HCQ or chloroquine is recommended in patients with mild active disease (without poor prognostic criteria), particularly in whom MTX is contraindicated.

Strong recommendation.

The use of HCQ in combination with other csDMARDs is recommended in patients with moderate to severe activity.

Strong recommendation.

Sulfasalazine (SSZ)In a systematic review Rempenault et al. evaluated SSZ as monotherapy vs. HCQ as monotherapy or SSZ + HCQ. The efficacy of HCQ and SSZ as monotherapy was similar. However, in a double-blind randomised clinical trial (RCT), radiographic progression rates at 48 weeks were significantly higher with HCQ than with SSZ (p < .02).27 Another double-blind RCT found no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. However, the ACR20 and ACR50 response percentages were higher at 2 years with triple therapy (MTX + SSZ+HCQ) than with MTX + SSZ combined (78 vs. 49%; p: 02 and 55 vs. 29%; p: .005, respectively). In the safety aspect, no additional AEs were reported, the most frequent being gastrointestinal and cutaneous.26

Certainty of the evidence: Moderate ⊗⊗⊗○

RecommendationsThe use of SSZ is recommended in case of contraindication to MTX or in patients with moderate to severe activity in combination with other scDMARDs.

Strong recommendation

Biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugsTumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitorsbDMARDs generated as monoclonal antibodies (infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab), or as fusion (etarnecept) and pegylated (certolizumab) proteins, have a mechanism of action which inhibits the effects of tumour necrosis factor α (TNF) on the pathways of inflammation and tissue destruction that operate in RA, either in the modalities of original or biocomparable molecules. They have unquestionably demonstrated their effectiveness in the treatment of RA. In the previous updated version of the MCR pharmacological treatment guidelines for RA, the recommendation was made to use these agents and the recommendation was unconditionally supported by high quality evidence. Included in this recommendation was the use of JAK inhibitor drugs in patients with RA with moderate to high activity with inadequate response to treatment with csDMARDs.30

Additionally, in the previous version of the aforementioned MCR guidelines, switching to another TNF inhibitor drug or another bDMARD with a different mechanism of action in the case of failure to a first TNF inhibitor, was strongly recommended with a high-quality grade of evidence.

The Recommendations of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) and the guidelines of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) are in accordance with the fundamental recommendation for the use of TNF inhibitors issued by the MCR, the recommended actions for when to switch to bDMARDs from csDMARDs, the sequence of discontinuation of management in patients on bDMARDs, as well as for the type of bDMARDs or designer synthetics, such as JAK inhibitors, which should be used as first line medication in the case of failure to manage with csDMARDs, or in case of primary or secondary failure to treat with a TNF inhibitor.31,32 Accordingly, the ACR conditionally recommends direct transition to bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors in the case of failure (defined by inability to achieve the therapeutic goal) to management with MTX monotherapy, without the prior step to combination therapy with csDMARDs. The ACR guidelines also conditionally recommend the initial gradual reduction of MTX over that of bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors in patients with RA who have achieved the therapeutic goal for at least 6 months and the recommendation of non-TNF inhibitor DMARDs use in cases of heart failure manifestations or development.

Finally, the EULAR recommends that, in patients with cardiovascular, neoplastic, thromboembolic disease risk factors, or those over 65 years of age, the initial use of bDMARDs (including TNF inhibitors) over JAK inhibitors should be prioritised.31

He et al. conducted an online meta-analysis, which could be classified as having a high risk of bias, but showed a moderate level of certainty in its conclusions, since it included 72 RCT studies with a total of 28,332 patients. According to the SUCRA analysis performed, certolizumab pegol had a greater association with the development of global AEs, serious AEs, and severe infections compared to the other TNF-inhibitor agents. No significant differences were identified between the different TNF inhibitors in terms of the risk of subsequent malignancies.33

Furthermore, through an online meta-analysis, which could be classified as having a high risk of bias and very low certainty in its conclusions because the 10 articles included were carried out with a cohort design, Xie et al. aimed to compare the oncological safety between different options of csDMARDs, bDMARDs (TNF inhibitors, anti-IL-6, anti-CD20) and tofacitinib. The TNF-inhibitor patient arm included 166,073 patients (471,654 patients/years of exposure). In this study, no differences were found in the overall cancer incidence between patients treated with TNF inhibitors compared to those treated with rituximab (HR: 1.9; 95% CI: .92–1.29); tocilizumab (HR: .94; 95% CI: .72–1.23), and tofacitinib (HR: 1.04; 95% CI: .68–1.61). Significantly, an increased risk of overall cancer was found when comparing patients treated with abatacept to those treated with TNF inhibitors (HR: 1.21: 95% CI: 1.11–1.33).34

Quality of evidence: Moderate ⊗⊗⊗○.

RecommendationsThe use of bDMARDs (without preference for mechanism of action) or JAK inhibitors is recommended in patients with RA, taking into account their safety profile, with moderate to high activity and inadequate response to treatment with csDMARDs

Strong recommendation

First-line use with bDMARDs (without preference for mechanism of action) or JAK inhibitors is recommended in patients with RA, without prior disease-modifying treatment, and with poor prognostic factors.

Strong recommendation

Switching to a disease-modifying drug with a different mechanism of action is recommended in patients with RA with moderate or severe activity with inadequate response to bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors.

Strong recommendation

The use of tocilizumab or a JAK inhibitor is recommended in patients with RA with moderate to severe activity for whom monotherapy has been indicated.

Strong recommendation

The use of TNF inhibitors in the treatment of patients with RA who have not previously been exposed to csDMARDs is suggested if they have poor prognosis markers, if they are resistant to csDMARDs, especially if MTX or LEF were used, and in patients resistant to bDMARDs.(other mechanisms of action) or a JAK inhibitor.

Conditional recommendation

Intentionally monitoring for the appearance or reactivation of tuberculosis (Tb), or the appearance of opportunistic infections, demyelinating disorders, serious cardiovascular events or cancer is recommended in patients with RA on treatment with b-DMARDs or JAK inhibitors.

Strong recommendation

Abatacept (ABA)According to Endo et al.,35 ABA performed less adequately in RA patients with positive anti-Ro antibodies. Those with negative anti-Ro had a greater decrease in DAS-28 ESR and CRP scores, with statistically significant differences at 12 months. In the study by Pappas et al.,36 when analysing data from a US registry that included 46,414 patients with RA, no differences were found between TNF inhibitors and non-TNF-inhibitor bDMARDs, in obtaining low disease activity or remission; minimal clinically relevant effect from CDA, or disturbances in sleep or anxiety. Overall, there was no difference in effectiveness. In the ASCORE study by Alten R et al.,37 based on routine clinical practice, it was shown that the persistence of ABA at 2 years was 47%. Retention was highest in the group of patients who were seropositive for FR or ACPA. The study by Tardelia M et al.,38 showed that patients with RA and interstitial lung disease had an adequate response with little progression in the majority of them, both in treatment with ABA and with JAK inhibitors. Rigby et al.39 reported a post hoc analysis of the AMPLE study, which compared ABA vs. adalimumab (ADA) in a population naïve to biologics, in whom the presence of a shared epitope increased the relative efficacy of ABA over ADA, with a higher remission rate due to SDAI or CDAI in the group treated with ABA. The presence and titre of anti-CCP2 predicted the response to ABA.

This response in ACPA + patients was also confirmed by Harrold et al.,40 but with anti-CCP3. There was an inverse correlation with anti-CCP3 concentrations per quartile with response in CDAI and all PROs (patient-reported pain, pFGA, MHAQ, and fatigue). This correlation was not observed in those treated with TNF inhibitors. The response to TNF inhibitors was lower in patients with high anti-CCP3 titres. This greater effect of ABA vs. TNF inhibitors in ACPA seropositive RA was confirmed in the study by Kin et al.41 which is based on the Korean national registry, and in which ACPA-positive RA patients had a better clinical response measured by CDAI.

The advantages of using ABA over TNF inhibitors are not only observed in the clinical response, but also in the cost per patient achieving a response, according to the study by Park et al.42 in which the cost for a clinical response was lower with ABA in RA patients seropositive to aCCP.

Results regarding the long-term survival of the different treatments with DMARDs or scDMARDs are controversial in some studies, such as that of Choi et al.,43 which indicates that the survival of ABA, tocilizumab and tofacitinib was superior to etanercept as first, second and third drugs. However, in an analysis of 31,846 patients from 19 registries, published by Lauper et al.44 the survival of ABA was superior to that of TNF inhibitors, but inferior to that of anti-interleukin 6 (anti-IL6) drugs and tofacitinib.

Certainty of the evidence: Low ⊗⊗○○

RecommendationsThe use of ABA is recommended in patients with RA who have not previously been exposed to csDMARDs; in those with poor prognostic factors; in patients resistant to csDMARDs, or in patients with failure to other biologics or JAK inhibitors.

Strong recommendation

Anti-interleukin 6 drugsRegarding effectiveness (assessed by DAS28-ESR, ACR20 response, ACR50, ACR70, HAQ-DI, DAS28-ESR remission, VAS pain, global VAS of the disease), tocilizumab was more effective than placebo in achieving ACR20 RR 3 .70 (1.84–7.24), ACR 50 RR: 14.29 (1.95–104.44) and remission by DAS28-VSG RR: 17.36 (2.40–125.29).45 Spacing the weekly dose of 162 mg of tocilizumab to every 2 weeks was associated with lower efficacy in maintaining remission at 24 weeks.46

Sarilumab obtained a better efficacy rate to achieve ACR50 when compared with placebo + MTX, sarilumab 200 mg, OR: 4; 95% CI: 2.04–8.33; 200 mg sarilumab + MTX, OR: 3.75; 95% CI: 2.37–5.72 and 150 mg sarilumab + MTX, OR: 2.83; 95% CI: 1.82–4.4.47 200 mg Sarilumab every 2 weeks had improvement in HAQ-DI, mean difference of −0.18; 95% CI: –0.31 to –.06, VAS pain, mean difference of –8.78; 95% CI: –13.66−3.9 and global VAS of the disease mean difference of –8.48; 95% CI: −13.24 to −3.72) vs. 40 mg subcutaneous (SC) adalimumab every 2 weeks.48 100 mg SC Sirukumab every 2 weeks had a better efficacy rate to achieve DAS28-ESR remission when compared with 40 mg SC adalimumab every 2 weeks RR: 2.70 (1.51–4.81).49 No differences were found when comparing the dose of 50 mg SC sirukumab every 4 weeks with 100 mg SC sirukumab every 2 weeks. Both doses showed improvement in joint symptoms, physical function and inhibition of structural damage when compared with placebo.50

Regarding the safety aspect (evaluated by rate of AEs, infections, serious infections, infestations, major cardiovascular events, acute myocardial infarction) it was found that tocilizumab vs. rituximab had an RR: 5.41; 95% CI: 1.70–17.26, for serious cardiovascular events, without differences when compared with other DMARDs and TNF inhibitors. Tocilizumab vs. placebo had a higher risk of adverse events RR: 1.42; 95% CI: 1.13–1.78.51 When comparing AEs between 200 mg SC sarilumab every 2 weeks vs. 8 mg/kg tocilizumab intravenously every 4 weeks, there were no significant differences.52 When comparing 50 mg SC sirukumab every 4 weeks with 100 mg SC sirukumab every 4 weeks, there were no differences in serious AEs, serious infections, mortality and cardiovascular events.53

Certainty of the evidence: Very low ⊗⊗○○.

RecommendationsTocilizumab is recommended for the treatment of patients with RA who have not previously been exposed to csDMARDs if they have poor prognostic markers; in patients resistant to csDMARDs, especially if they used MTX or LEF, and in patients resistant to bDMARDs (with other mechanisms of action) or JAK inhibitors.

Strong recommendation

Its use in combination with csDMARDs or as monotherapy is recommended.

Strong recommendation

Rituximab (RTX)Five studies referring to RTX (one systematic review, 2 meta-analysis and one RCT) that compared MTX, LEF, anakinra, golimumab, tofacitinib, etanercept, tocilizumab, abatacept, infliximab, certolizumab, TNF-inhibitor bDMARDs and non-TNF-inhibitor bDMARDs were evaluated. In the area of effectiveness (evaluated by ACR20 response, ACR50, ACR70, HAQ, DAS28 remission, low DAS28 activity, good EULAR response, CDAI50%) RTX in early RA reached ACR70 in 52,8%.54 The use of RTX + MTX had an RR: 1.74 (1.53–1.98) for ACR70, compared to MTX alone.55 Regarding the use of low doses (500 mg on day 1 and day 15), there were no differences vs. LEF (10−20 mg/day) + MTX (10−20 mg/wk).56 RTX (1,000 mg on day 1 and day 15), compared to tocilizumab (infusion of 8 mg/kg/every 4 weeks), achieved CDAI50% improvement with an RR: 1.71 (1.01–2.09).57 Regarding safety (evaluated by rate of infections, serious infections, serious adverse events and neoplasias) it was observed that RTX vs.TNF inhibitor had an RR: .47 (.30–.73) for the presence of any infection.58

Certainty of the evidence: Moderate ⊗⊗⊗○

RecommendationsThe use of RTX is suggested for the treatment of patients with RA who have not previously been exposed to csDMARDs if they have poor prognosis markers; in patients resistant to csDMARDs, especially if they used MTX or LEF, and in patients resistant to bDMARDs (with other mechanisms of action) or JAK inhibitors.

Conditional recommendation

JAK inhibitorsJAK inhibitors are a new class of drugs with an adequate efficacy and safety profile. These drugs are associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic effects, particularly due to the activity of the inflammatory process. The effect of JAK inhibitors on cardiovascular risk and the atherosclerosis process as the main contributor to serious adverse cardiovascular events has been shown to be protective, as has been demonstrated for other DMARDs.59

Studies conducted with JAK inhibitors (in monotherapy or in combination with MTX or LEF) have demonstrated superior efficacy to that achieved with scDMARDs in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe RA. Two meta-analyses showed that the efficacy of JAK inhibitors, assessed by DAS28, ACR 20, 50 and 70, as well as remission rates by DAS, SDAI and CDAI, are equivalent to those achieved with biological therapies. This applied to both in patients with prior failure to MTX, and in patients with prior failure to other bDMARDs.60 Compared to the general population, studies show that patients with RA have a higher risk of thromboembolism. The risk is independent of traditional venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk factors, is highest during the first year after RA diagnosis and subsequently progressively decreases.61,62

Regarding infections, a meta-analysis of 21 studies found that the absolute rates of serious infections associated with JAK inhibitor treatment were low. Opportunistic infections, including TB, are uncommon. There is a higher incidence of herpes zoster compared to that expected for the general population (3.23 per 100 years/patient), and the risk of infectious events may decrease with the reduction or elimination of concomitant GCs.63

Malignancy rates do not appear elevated with JAK inhibitors, although the risk of non-melanoma skin cancer may be higher. Other AEs described are lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia and anaemia, as well as an increase in CK and serum creatinine without association with muscular clinical events, renal failure or high blood pressure.

Absolute contraindications for its prescription are serious active (or chronic) infections, including TB and opportunistic infections; current malignant neoplasms; severe organ dysfunction, such as liver disease (Child-Pugh C) or kidney failure; pregnancy and lactation, and recurrent VTE (unless the patient is on anticoagulants).31,64

Certainty of the evidence: Very low ⊗○○○

RecommendationsJAK inhibitor use is recommended for the treatment of patients with RA who have not previously been exposed to csDMARDs if they have poor prognostic markers; in patients resistant to csDMARDs, especially if they used MTX or LEF, and in patients resistant to bDMARDs.

Strong recommendation

The combined use of JAK inhibitors with csDMARDs or as monotherapy is suggested.

Conditional recommendation

The detection of risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease, neoplasia and risks prior to treatment is suggested. Also, the performance of specific laboratory tests (blood count, liver function tests, kidney function, lipid levels); hepatitis B and C testing; human immunodeficiency virus testing in high-risk populations; TB detection, and evaluation and updating of vaccination status.

Conditional recommendation

The use of recombinant particle herpes zoster vaccine in patients treated with JAK inhibitors is suggested as a consideration.

Conditional recommendation

Caution is suggested when the following risk factors exist when prescribing a JAK inhibitor:

- •

Age over 65 years.

- •

A history of either a current or past smoking habit.

- •

Cardiovascular risk factors (such as diabetes, obesity, or high blood pressure).

- •

Risk factors for malignancy (current or previous history of malignancy other than successfully treated non-melanoma skin cancer).

- •

Risk factors for thrombotic events (history of myocardial infarction or heart failure, cancer, inherited blood clotting disorders or history of blood clots, as well as patients taking combined hormonal oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, undergoing major surgery or immobile).

- •

Consider dose adjustments in patients >70 years of age, with significant renal or hepatic impairment, and/or risk of drug interactions, or as a result of other comorbidities, based on individual product information.

Conditional recommendation

BiocomparablesWe evaluated four studies (two online meta-analyses and two RCTs) comparing MTX, adalimumab, etanercept, RTX, and placebo. In terms of effectiveness (evaluated by ACR20, ACR50, ACR70, DAS28-PCR response and CDAI remission) for ACR20 no difference was found when comparing adalimumab biosimilar + MTX vs. adalimumab + MTX, OR: 1.04 (95% CI: .67–1.66).65 Biocomparable adalimumab (CT-P17) and adalimumab (EU) had similar efficacy in achieving remission through CDAI, RR: .95 (.73–1.23).66 No difference was found in the efficacy rate for ACR20 when comparing etanercept biocomparables (LBEC0101, HD203 or SB4).67

In terms of safety (assessed by rate of AEs, treatment abandonment and serious AEs), no difference was found in the number of AEs when comparing adalimumab biocomparable + MTX vs. adalimumab + MTX vs. placebo + MTX.66

RTX (GP2013) had a similar rate of AEs RR: 1.08 (91−1.27), serious AEs RR: 93 (.52–1.71) and treatment dropouts RR: .72 (.30–1.77) than its original comparator.68

Certainty of the evidence: Low ⊗⊗○○

RecommendationsThe use of biocomparables to achieve ACR20 and remission by CDAI in the RA population is similar to its original comparator.

Conditional recommendation

There are no differences in AE compared with the original biologics.

Conditional recommendation

Special populationCardiovascular riskIn recent years updating has mainly focused on JAK inhibitors. The ORAL Surveillance study is a large (n: 4362), randomised, non-inferiority, active-controlled clinical study which evaluates the safety of tofacitinib with two doses (5 and 10 mg/2 times a day) vs. a TNF inhibitor (adalimumab or etanercept) in RA patients aged 50 years or older who had at least one additional cardiovascular risk factor: smoking, systemic arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes or a history of coronary heart disease. The cardiovascular endpoints of this study were confirmed major cardiovascular AEs (MACE). To consider the study completed, follow-up of at least 1,500 patients for 3 years was required. The results showed that the pre-specified non-inferiority objectives of tofacitinib vs. a TNF inhibitor were not obtained. The results suggested that these risks were associated with the two dosing regimens. Results included 135 patients with confirmed MACE. The most frequently observed MACE was myocardial infarction. In those patients with a higher prevalence of known risk factors for MACE (e.g., older age, smoking habit), a higher incidence of events was observed. Regarding the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), it was found that at the dose commonly used of tofacitinib in RA (5 mg/every 12 h) the risk was very similar to that derived from the use of the 2 TNF inhibitors that it had been compared with.69

Because these preliminary results from the ORAL Surveillance study showed an increased incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients treated with tofacitinib compared to those treated with a TNF inhibitor, the FDA issued an alert that impacted the recommendation of the latest ACR guidelines regarding the initial use of a bDMARD before a JAK inhibitor, in patients resistant to csDMARDs.70

In the EULAR guidelines, a weighting of the evidence was made and the recommendation is that in older patients and with additional cardiovascular risk factors, in whom csDMARDs do not achieve disease control, treatment with JAK inhibitors should be avoided and another available therapeutic alternative (bDMARD) used.71

ThrombosisParticular caution is recommended with the use of baricitinib in patients with risk factors for DVT or PTE. In Mexico, the presentations of 2 and 4 mg/every 24 h h72 are approved. The FDA in the United States of America only approved the presentation of 2 mg, in consideration of thrombosis events.73

In a recent systematic review with meta-analysis, the risk of cardiovascular event has OR: 2.33 (baricitinib vs. placebo for DVT). A lower risk of MACE cardiovascular event or peripheral venous thrombosis was reported when comparing the lower dose of baricitinib of 2 mg vs. 4 mg.74

Lipid profileElevation of total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol, without changes in the total cholesterol/HDL ratio, has been described in up to 49% of patients treated with JAK inhibitors, being more frequent during the first 3 months of treatment.75 These changes are generally reversed with statins.76

Certainty of the evidence: Low ⊗⊗○○

RecommendationsWhilst there is no greater strength in the evidence on the modification of cardiovascular risk in the population with RA and JAK inhibitors, this type of medication should be indicated with caution, assessing the risk-benefit in patients with RA and cardiovascular disease with concomitant risk factors.

Conditional recommendation

InfectionsTuberculosis (Tb)In a meta-analysis of 39 randomised studies, a higher risk of TB (OR: 3.86) with TNF inhibitors was observed in 9.21/1,000 exposed patients, although the risk was also high for those who received tocilizumab (OR: 5.98) and tofacitinib (OR: 7.39), and lower with the use of csDMARDs.77 The increased risk for TB is not restricted to those individuals with a positive tuberculin or a positive or indeterminate interferon-gamma release test (IGRA), as reported in a systematic review of 20 randomised studies.78

Certainty of the evidence: Low ⊗⊗○○

RecommendationsHepatitis BIn the use of intense immunosuppression, the Hepatitis B virus, even in an inactive state and without viral load, creates a potential risk of exacerbation and of expressing both disease activity with viral load, with or without laboratory biomarkers, and also the development of severe liver failure.82,83 The latter is particularly relevant with the use of B cell depletion therapy (RTX) and T cell co-stimulation inhibitor (ABA), as reported in 2 observational studies that with moderate certainty highlighted the significant association, and the multiple increased high risk.84–86 RTX increases the risk of hepatitis B reactivation (OR: 7.2; 95% CI: 5.3–99), thus its administration should be monitored in these patients and its use should be avoided in cases of active infection.87,88 Latent HBV infection, defined as the presence of serum HBV ADN and undetectable hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), can cause reactivation of HBV infection in patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy and can lead to acute deadly liver failure.83,85,89–95 Although there are reports of exacerbation of RA activation in patients receiving the HBV vaccine, it is generally considered safe and effective for them.83

Certainty of the evidence: Low ⊗⊗○○

RecommendationsPatients receiving biological agents are recommended to be screened for the presence of HBV.

Strong recommendation

The non-use of RTX in patients with RA and hepatitis B is suggested.

Strongly against.

It is suggested that patients with RA and HBsAg negative, anti-hepatitis B core (HBc) positive patients (with or without anti-HBs and undetectable HBV ADN) be closely monitored by HBV ADN quantification during and at least 12 months after immunosuppressive treatment, if available. Antiviral treatment should be started once HBV ADN is detectable (Table 1).

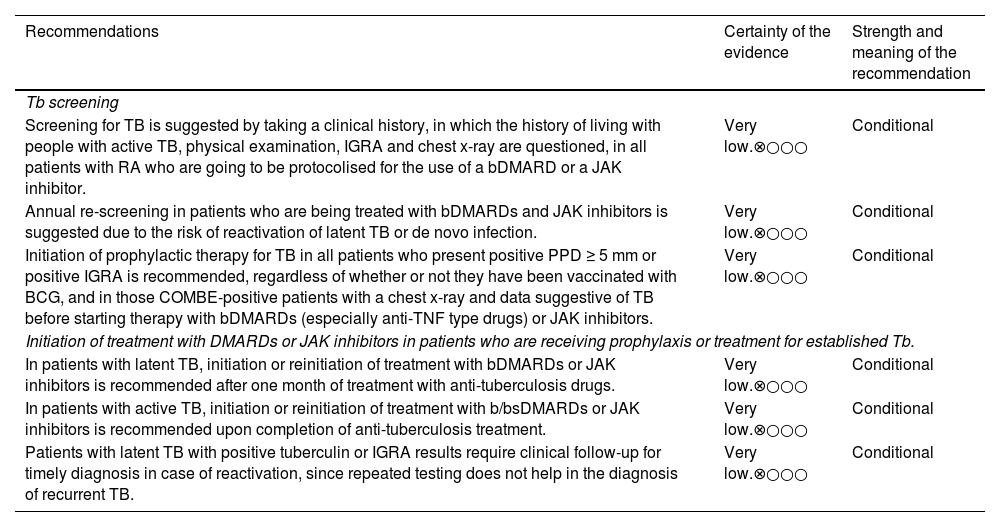

TB screening and management.

| Recommendations | Certainty of the evidence | Strength and meaning of the recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Tb screening | ||

| Screening for TB is suggested by taking a clinical history, in which the history of living with people with active TB, physical examination, IGRA and chest x-ray are questioned, in all patients with RA who are going to be protocolised for the use of a bDMARD or a JAK inhibitor. | Very low.⊗○○○ | Conditional |

| Annual re-screening in patients who are being treated with bDMARDs and JAK inhibitors is suggested due to the risk of reactivation of latent TB or de novo infection. | Very low.⊗○○○ | Conditional |

| Initiation of prophylactic therapy for TB in all patients who present positive PPD ≥ 5 mm or positive IGRA is recommended, regardless of whether or not they have been vaccinated with BCG, and in those COMBE-positive patients with a chest x-ray and data suggestive of TB before starting therapy with bDMARDs (especially anti-TNF type drugs) or JAK inhibitors. | Very low.⊗○○○ | Conditional |

| Initiation of treatment with DMARDs or JAK inhibitors in patients who are receiving prophylaxis or treatment for established Tb. | ||

| In patients with latent TB, initiation or reinitiation of treatment with bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors is recommended after one month of treatment with anti-tuberculosis drugs. | Very low.⊗○○○ | Conditional |

| In patients with active TB, initiation or reinitiation of treatment with b/bsDMARDs or JAK inhibitors is recommended upon completion of anti-tuberculosis treatment. | Very low.⊗○○○ | Conditional |

| Patients with latent TB with positive tuberculin or IGRA results require clinical follow-up for timely diagnosis in case of reactivation, since repeated testing does not help in the diagnosis of recurrent TB. | Very low.⊗○○○ | Conditional |

BCG: bacillus Calmette and Guérin (tuberculosis vaccine); bDMARDs: biological disease-modifying drugs; IGRA: interferon gamma release; JAK inhibitors: protein kinase inhibitors; PPD: purified protein derivative, tuberculin test; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; Tb: tuberculosis.

Conditional recommendation

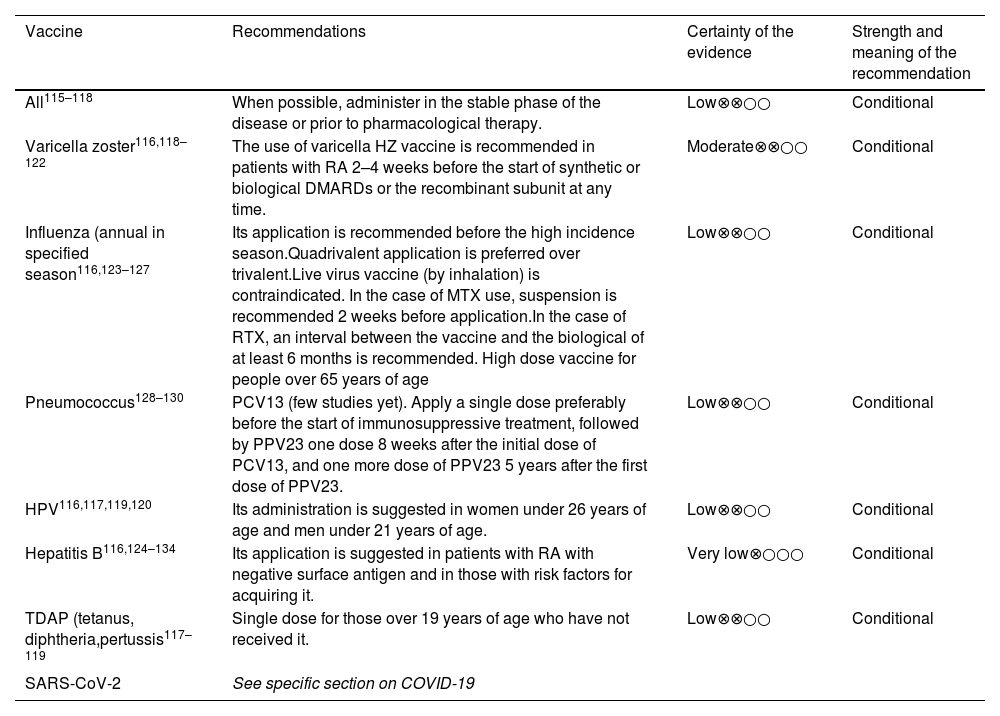

Vaccination is recommended for patients at risk of HBV infection, in keeping with the guidelines in Table 2.

Vaccination in RA patients.

| Vaccine | Recommendations | Certainty of the evidence | Strength and meaning of the recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| All115–118 | When possible, administer in the stable phase of the disease or prior to pharmacological therapy. | Low⊗⊗○○ | Conditional |

| Varicella zoster116,118–122 | The use of varicella HZ vaccine is recommended in patients with RA 2–4 weeks before the start of synthetic or biological DMARDs or the recombinant subunit at any time. | Moderate⊗⊗○○ | Conditional |

| Influenza (annual in specified season116,123–127 | Its application is recommended before the high incidence season.Quadrivalent application is preferred over trivalent.Live virus vaccine (by inhalation) is contraindicated. In the case of MTX use, suspension is recommended 2 weeks before application.In the case of RTX, an interval between the vaccine and the biological of at least 6 months is recommended. High dose vaccine for people over 65 years of age | Low⊗⊗○○ | Conditional |

| Pneumococcus128–130 | PCV13 (few studies yet). Apply a single dose preferably before the start of immunosuppressive treatment, followed by PPV23 one dose 8 weeks after the initial dose of PCV13, and one more dose of PPV23 5 years after the first dose of PPV23. | Low⊗⊗○○ | Conditional |

| HPV116,117,119,120 | Its administration is suggested in women under 26 years of age and men under 21 years of age. | Low⊗⊗○○ | Conditional |

| Hepatitis B116,124–134 | Its application is suggested in patients with RA with negative surface antigen and in those with risk factors for acquiring it. | Very low⊗○○○ | Conditional |

| TDAP (tetanus, diphtheria,pertussis117–119 | Single dose for those over 19 years of age who have not received it. | Low⊗⊗○○ | Conditional |

| SARS-CoV-2 | See specific section on COVID-19 | ||

DMARDS: disease-modifying drugs; HZ; Herpes zoster; MTX: methotrexate; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; RTX: Rituximab.

Strong recommendation

Vaccination is recommended for HBV-seronegative RA patients, at high risk of exposure to HBV.

Strong recommendation

The application of the HBV vaccine is suggested in patients with RA with negative surface antigen and in those with risk factors for acquiring it.

Strong recommendation

Herpes zoster (HZ)The prevalence of HZ is higher in patients with chronic systemic rheumatologic diseases with an autoimmune background than in the general population, particularly for those with greater disease activity and under immunomodulatory treatment. The above is relevant for patients under treatment with csDMARDs and specifically for biologics, and even more so for those receiving small molecules (JAK inhibitors). The relative risk of HZ ranges from 1.38 to 2.86, and does not appear to be particularly restricted to variable inhibition of one or more of the various kinases. In the majority of people who present HZ (>90%), this is limited from 1 to 3 dermatomes and the prevalence appears to be lower in the Latin American population.63

Certainty of the evidence: Moderate ⊗⊗⊗○

RecommendationsIn the event of the appearance of HZ, the suspension of immunosuppressive treatment is recommended until complete healing of the lesions is achieved.

Strong recommendation

Interstitial lung disease (ILD)Recent studies suggest that the lung can compete with the synovial membrane, as the original organ of RA, with ILD, frequently observed. In a longitudinal study of 1,419 participants, Sparks et al., mentioned disease activity and seropositivity as associated factors, in addition to the fact that non-specific ILD was far more frequent.96

In a systematic review Kamiya et al.,97 emphasized that age at diagnosis of ILD is a factor for acute exacerbations, HR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.05−1.5. Bonilla et al.98 highlighted smoking and seropositivity as relevant factors for the development of ILD. Dawson et al.,99 based on 13 observational studies, found inconsistency of the potential positive or negative effect of MTX. In a systematic review of 43 observational studies, Carrasco et al.100 reported that MTX and LEF do not increase the incidence, complications or mortality of ILD. TNF inhibitors are associated with a higher incidence and poorer outcomes when compared with MTX, LEF, ABA and RTX, but there is no evidence concerning JAK inhibitors and antifibrotics, although there a lack of consensus regarding anti IL-6.

In vitro studies and in animal models have shown that pirfenidone inhibits the synthesis of collagen as a result of fibroblast differentiation and its deposition. The CAPACITY 004 study (phase 3, randomised and double-blind) showed the reduction in the decrease in forced vital capacity (FVC) in the pirfenidone group (193 vs. 235 ml; p = .001), without significant difference in the CAPACITY 006 study (p = .44). In the multinational placebo-controlled phase 3 ASCEND study, pirfenidone reduced disease progression, but there were no significant differences between the 2 groups in all-cause or pulmonary fibrosis-related mortality.101

In a systematic review, Vicente et al.102 observed improvement or stabilisation of ILD images between 76.6% and 92.7%, and in FVC or carbon monoxide diffusion capacity >85% in mean follow-up of 17.4–47.8 months, with the use of ABA. They also observed lower rates of worsening than with TNF inhibitors and a 90% reduction in the relative risk of deterioration of ILD at 24 months of follow-up in comparison with TNF inhibitors and csDMARDs, with no unexpected AEs being identified.

In a cohort study, Mena et al.103 reported a lower percentage of FVC decrease in favour of RTX, with a mean difference of −3.97; 95% CI: −7.07 to −.87.

Certainty of the evidence: Moderate ⊗⊗⊗○

RecommendationsWhen there is suspicion in an initial study for screening for ILD in RA, the performing of a high-resolution chest computed tomography (HRCT) is suggested, particularly when symptoms such as progressive dyspnoea and persistent cough exist, in the absence of primary cardiovascular disease.

Conditional recommendation

A plain chest x-ray as proof of screening is not suggested.

Strongly against

Other tools such as electronic auscultation or ultrasound appear to be promising, but recommendation is limited for their use as a first step in the diagnosis of ILD.

It is recommended that patients with RA who use MTX and LEF with ILD do not discontinue these disease-modifying medications.

Strong recommendation

The use of ABA or RTX over TNF inhibitors is recommended in patients with RA and ILD to achieve stabilisation of the lung disease.

Strong recommendation

The use of pirfenidone is not recommended in patients with ILD and RA.

Strongly against.

COVID-19

Vaccination.

The GDG found no evidence that an extended number of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine doses has an effect on the clinical outcomes of patients with RA.104 There is evidence to support that a greater number of vaccine doses increases immunogenicity against SARS-CoV-2.105

Certainty of the evidence: Very low ⊗○○○

RecommendationsThe application of the available SARS-CoV-2 vaccination schedule is recommended in the population with RA (if there are no contraindications).

Strong recommendation

Use of DMARDs and risk of COVID-19 infections.

Three observational studies were evaluated in relation to the use of HCQ and the probability of modifying the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections. None of the three studies reported modifying this risk.105–107

Certainty of the evidence: Very low ⊗○○○

RecommendationsThe use of HCQ to reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections in the RA population is not recommended.

Strongly against.

Use of bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors.

Five observational studies on the use of RTX in patients with RA and COVID-19 and its relationship with severe infections were evaluated and it was found that the use of RTX can increase the risk of severe COVID-19 up to 5 times in this population. No recommendation can be made regarding modification of treatment with other bDMARDs or JAK inhibitors to modify the risk of hospitalisation due to COVID-19.108–112

Certainty of the evidence: Very low ⊗○○○

RecommendationsThe discontinuation of RTX treatment in patients with RA and COVID-19 is recommended to reduce the risk of severe COVID-19 (including hospitalisation with supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation) and death.

Strong recommendation

Post-COVID-19 and long-term COVID-19 complications.

RA is not a risk factor for the presence of post-COVID-19 and long-term COVID-19 complications. No evidence was found that evaluates the impact of RA on the quality of life of patients with a history of SARS-COV-2 infection.113,114

Certainty of the evidence: Very low ⊗○○○.

RecommendationsIt is not suggested to consider RA as a risk factor for post-COVID-19 complications or long-term COVID.

Conditional recommendation

VaccinationRecommendationsContinuous updating and training on the use of vaccines in patients with RA is suggested.

Point of good practice.

A complete vaccination schedule in patients with RA is recommended, together with the use of synthetic or biological DMARDs.

Strong recommendation

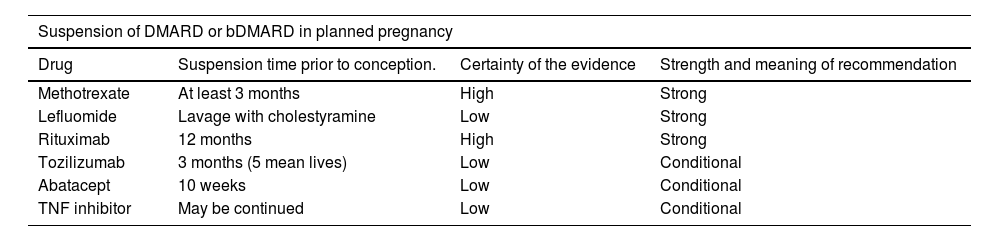

Pregnancy and breast feedingPregnancyFor the pregnant population with RA, due to disease activity, it is suggested when necessary to use HCQ or SSZ to control the disease during pregnancy (Table 3).

Pharmacological treatment of RA during pregnancy and breastfeeding.135–140*.

| Suspension of DMARD or bDMARD in planned pregnancy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Suspension time prior to conception. | Certainty of the evidence | Strength and meaning of recommendation |

| Methotrexate | At least 3 months | High | Strong |

| Lefluomide | Lavage with cholestyramine | Low | Strong |

| Rituximab | 12 months | High | Strong |

| Tozilizumab | 3 months (5 mean lives) | Low | Conditional |

| Abatacept | 10 weeks | Low | Conditional |

| TNF inhibitor | May be continued | Low | Conditional |

| Control of clinical activity in pregnancy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Recommended, suggested or contraindicated | Pregnancy stage in which it can be used | Certainty of the evidence | Strength and meaning of recommendation |

| Prednisone | Recommended | Throughout pregnancy | High | Strong |

| Anti-malaria drugs | Recommended | Throughout pregnancy | High | Strong |

| Sulfasalazine ≤2 g/d+5 mg/d of folic acid | Recommended | Throughout pregnancy | High | Strong |

| Azathioprine | Recommended | Throughout pregnancy | High | Strong |

| Certolizumab pegol | Suggested | Throughout pregnancy | High | Conditional |

| Infliximab | Suggested | First 20 Weeks | Low | Conditional |

| Adalimumab | Suggested | Throughout pregnancy | Moderate | Conditional |

| Etanercept | Suggested | Up to 30 Weeks | Low | Conditional |

| Golimumab | Contraindicated | Throughout pregnancy | Very low | Conditionally against |

| Biocomparable TNF inhibitor | Suggested | Throughout pregnancy | Very low | Conditional |

| Treatment during breast feeding | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | Additional considerations | Certainty of the evidence | Strength and meaning of recommendation |

| Prednisone | Dose equal to or less than 10 mg | High | Strong |

| NSAID | Those with a short half-life (e.g., ibuprofen) are suggested and to be administered after each breast-feeding. | Moderate | Conditional |

| Anti-malaria drugs | HCQ and chloroquine | High | Strong |

| Sulfasalazine | Not recommended in premature infants, with G6PD deficiency or hyperbilirubinaemia | Moderate | Conditional |

| Azathioprine | Caution in patients with thiopurine methyltransferase deficiency | Moderate | Conditional |

| Certolizumab pegol | Under the clinician’s responsibility | Moderate | Conditional |

| Methotrexate and leflunomide | Contraindicated | Moderate | Strongly against |

bDMARDs: biological disease-modifying drugs; DMARDS: disease-modifying drugs; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; TNF inhibitors: tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

Conditional recommendation

Evaluation of the use of certolizumab pegol is suggested for the pregnant population with RA, when necessary due to disease activity.

Conditional recommendation

Breast feedingIn the population with RA that is breastfeeding, when necessary due to disease activity, the use of HCQ or SSZ to control the disease during pregnancy is suggested (Table 3).

Conditional recommendation.

Pharmacological treatment in the perioperative periodCertainty of the evidence: Low ⊗⊗○○

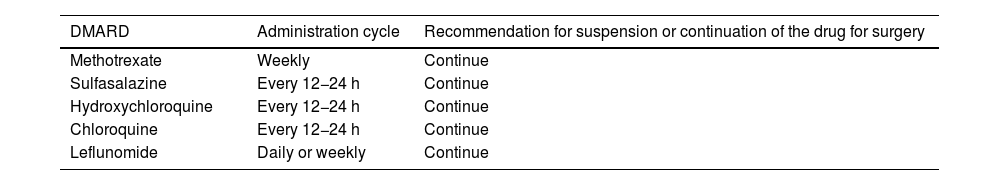

The continuation of csDMARDs in the RA population is recommended during the perioperative period (Tables 4 and 5).

Drugs that are recommended to continue in the perioperative period in the RA population.

| DMARD | Administration cycle | Recommendation for suspension or continuation of the drug for surgery |

|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate | Weekly | Continue |

| Sulfasalazine | Every 12−24 h | Continue |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Every 12−24 h | Continue |

| Chloroquine | Every 12−24 h | Continue |

| Leflunomide | Daily or weekly | Continue |

DMARDS: Disease-modifying drugs; RA: rheumatoid arthritis.

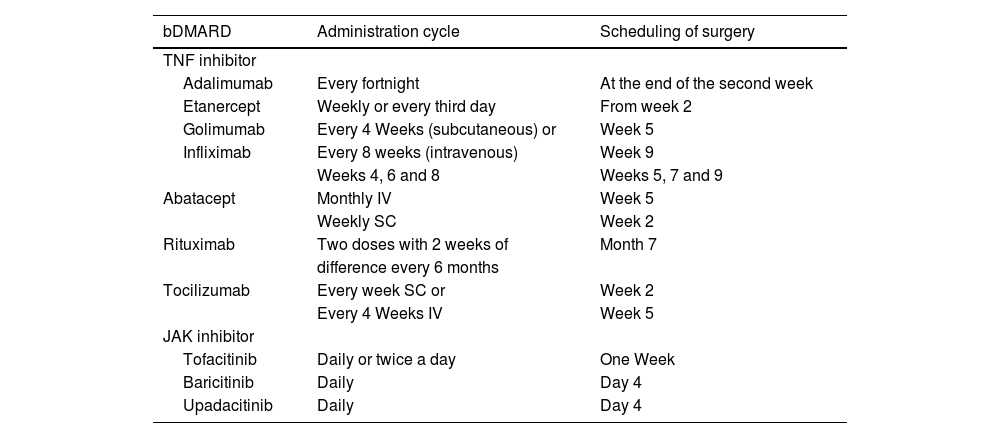

bDMARDs recommended to be suspended and for surgery to be scheduled on termination of the dose interval.

| bDMARD | Administration cycle | Scheduling of surgery |

|---|---|---|

| TNF inhibitor | ||

| Adalimumab | Every fortnight | At the end of the second week |

| Etanercept | Weekly or every third day | From week 2 |

| Golimumab | Every 4 Weeks (subcutaneous) or | Week 5 |

| Infliximab | Every 8 weeks (intravenous) | Week 9 |

| Weeks 4, 6 and 8 | Weeks 5, 7 and 9 | |

| Abatacept | Monthly IV | Week 5 |

| Weekly SC | Week 2 | |

| Rituximab | Two doses with 2 weeks of | Month 7 |

| difference every 6 months | ||

| Tocilizumab | Every week SC or | Week 2 |

| Every 4 Weeks IV | Week 5 | |

| JAK inhibitor | ||

| Tofacitinib | Daily or twice a day | One Week |

| Baricitinib | Daily | Day 4 |

| Upadacitinib | Daily | Day 4 |

bDMARDs: biological disease-modifying drugs; JAK inhibitors: protein kinase inhibitors; SC: subcutaneous; TNF inhibitors: tumour necrosis factor inhibitors.

Strong recommendation

The suspension of bDMARDs for at least the duration of one treatment cycle prior to the scheduled date of surgery in the RA population is recommended (Table 4).

Strong recommendation

Before restarting treatment with bDMARDs, verification of adequate healing of the surgical wound and absence of infection is suggested.

Point of good practice

It is suggested that the lowest possible dose of GC be used during the perioperative period. Assess the need for stress doses of GC or low to moderate doses, to avoid adrenal suppression.

Strong recommendation

OsteoporosisA meta-analysis conducted by Siu et al.146 evaluated the effect of GCs (chronic use, with a follow-up of 20 weeks to 2 years) on bone mineral density (BMD) in the population with RA. It was found that these had a negative effect on BMD changes in the lumbar spine, MD: –0.3; 95% CI: −0.55 to −0.04. This differs from what was reported by Blavnsfeldt et al.147 who found no difference in BMD in the lumbar spine or hip when comparing the use of GC vs. placebo in patients with recently diagnosed RA. Regarding the prevention of osteoporosis secondary to the GC use, a meta-analysis (which included 9 randomised clinical studies) reported that compared to vitamin D alone, bisphosphonates alone or in combination with vitamin D, BMD increased in the lumbar spine and femoral neck in patients with GC-induced osteoporosis.148

Less et al.149 evaluated the effect of TNF inhibitors on BMD density in patients with RA and found no difference in the median one-year percentage change in BMD in the lumbar spine or in the femoral neck. The same occurred in another study, in which it was found that the use of TNF inhibitors showed no changes in BMD in the lumbar spine MD: –.12; 95% CI: −.36 to .11, or in the hip MD: .2; 95% CI: −.11 to .51.146

In their review article Orsolini et al. comment that the IL-6 blockade could have a positive effect on general bone balance. The effect is limited to stabilisation or a small gain. Regarding JAK inhibitors, since they are relatively new drugs, no conclusions can be made regarding the bone health of patients with RA.150 Other authors mention that anti-IL-6 prevent bone damage, cartilage degeneration in patients with RA and delay bone loss progression. They also indicate that JAK inhibitors induce bone repair by altering gene expression and increasing osteoblast activity in murine models.151

Regarding RTX, Al Khayyat et al. reported an increase in BMD compared to baseline after 18 months of treatment (1.031 ± .11 vs. 1.11 ± .1). No difference was found in BMD at the femoral neck after the same treatment time.152

In a cohort study, Tada et al. found that compared to other bDMARDs, ABA had a greater probability of increasing BMD in the femoral neck, but this did not occur in the lumbar spine.153 Another cohort study compared BMD modification with ABA vs. csDMARDs and TNF inhibitors. When comparing ABA against csDMARDs, they reported a significant difference in favour of ABA in all the sites measured: +.8 vs.−2.7% in the femoral neck, +.5 vs.−1.1% in the hip and +.8 vs. –2% in the lumbar spine. When comparing it against TNF inhibitors, the same occurred.: there was a significant difference in favour of ABA: +.8 vs. –1.8% in the femoral neck, +.5 vs. –1% in the hip and +.8 vs.−3.5% in the lumbar spine.154

Certainty of the evidence: Low ⊗⊗○○

Bioethical aspectsThe patient-centred care model is optimal for the management of chronic diseases, which include RA, and has been shown to have a positive impact in terms of effectiveness, safety, and treatment adherence.152,155 Patient-centred care is defined as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.” 156 This model presupposes an exchange of information between the clinician and the patient, which is then integrated into the treatment plan and considers the patient’s individual characteristics from a biopsychosocial perspective that provides a complementary vision in the evaluation of treatment-derived risks and benefits.157 In short, the model recognises shared decision-making as a necessary activity for its operationalisation.

Shared decision-making implies respect for the principle of autonomy (PA) and patient self-determination in health-related issues.157,158 The PA establishes that every person must have the opportunity to decide for themselves what to do, without coercion, in situations that are important to and concern them. Medical practice means respecting the patient's freedom to decide for themselves on health-related issues. There are different conceptualisations of PA. The prevalent model is the liberal and individualistic interpretation proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, in which a patient is autonomous to the extent that they may choose, act intentionally, understand and control the elements that can influence their decisions.159 Here the relevant highlight is that autonomy conceptualised as negotiated consent emphasizes interpersonal and social communication, in which clinician and patient focus on mutual understanding. This concept of PA, which differs from that proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, is a better match with shared decisión-making.160

Brief mention should be made of the principle of justice and its relationship with the PA. The principle of justice is the equitable distribution of rights, benefits, responsibilities or burdens among the members of society. In the area of health, it involves the equitable distribution of available resources, which includes access to medicines (particularly high-cost ones). According to principle-based ethics there are four cardinal principles: autonomy; beneficence; non-malfeasance, and justice, which rank the same and are prima facie, that is, they are always binding, unless a conflict between them exists. Gracia161 (doctor, philosopher and bioethicist) proposes a hierarchy of principles to resolve the potential tension between PA and justice. For the author, PA and beneficence are explained with reference to the person, the bearer of a belief system, from which this person defines their private life project and this implies the maximum to which every person aspires. The principles of justice and non-malfeasance, however, correspond to the elements that ensure survival, as a basis for subsequent decision-making of a personal nature. They belong to the public sphere and define a level of minimums, which enables maximums. For the author, the defence of personal freedom cannot endanger the obligations of justice. In other words, these guidelines, which emphasize PA and shared decision-making, will only have value in public settings that guarantee equitable and universal access to health care.

DiscussionAlthough different updated therapeutic guidelines for the treatment of RA have been published by various societies, it is important that the recommendations given consider the nature of the patients locally and the benefits and limitations that the local health system provides, in order to achieve a progressive improvement of treatment alternatives, detect barriers to access, and generate joint strategies with authorities and patient groups.

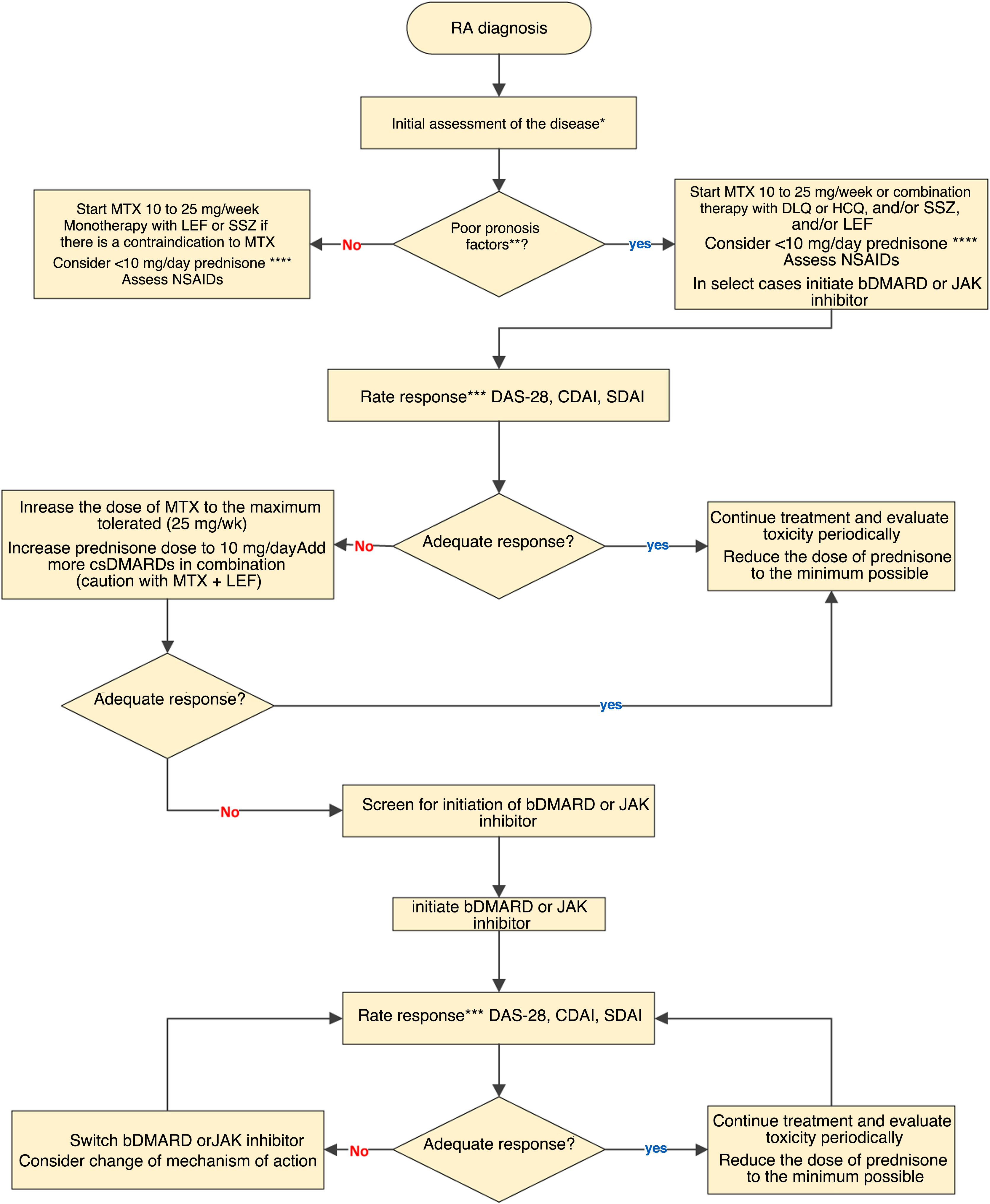

In this edition, a group of MCR experts has updated its RA treatment guidelines, and included specific modifications to its treatment algorithm (Fig. 1). The main contributions of this update are as follows: a collegiate position is established regarding the use of GC in the treatment of arthritis, leaving its use to the discretion of the rheumatologist, partly based on the accessibility of other agents. Safety information specific to JAK inhibitors is included. Regarding JAK inhibitors and RA, recommendations are included on cardiovascular safety, cancer and thrombophilias. This update aims to incorporate the best treatment strategies on an individualised basis and stresses the importance of the availability of at least some of these high-cost medications in the different health subsystems. As in previous versions, the relevance of patient participation in decision-making is highlighted.

RA treatment algorithm: bDMARD: biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; CDAI: Clinical Disease Activity Index; csDMARDs: conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug; CQL: chloroquine; DAS28: Disease Activity Score 28; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; LEF: leflunomide; MTX: methotrexate; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs SDAI: Simplified Disease Activity Index; SSZ: sulfasalazine.

*Initial clinical, serological and radiological evaluation of the disease.

**Poor prognostic factors: seropositivity with very high levels of RF or ACPA, erosive disease, high level of clinical activity and extra-articular manifestations.

***The assessment of the clinical response can be from 4 to 12 weeks in the case of active disease, every 12 weeks in the case of a low level of activity and up to every 6 months in the case of sustained remission without neglecting pharmacovigilance. An adequate response is considered to be clinical remission or a low level of activity.

****At the lowest possible dose and time.

Appropriate treatment of RA must include more efficient systems and processes, with an optimal number of committed rheumatologists, who have sufficient time to provide adequate care, in addition to pharmacological options that allow good disease control. None of the above can be achieved without government support and the commitment of all participants.

These recommendations, endorsed by the MCR, were developed by a group of experts in the clinical aspects, evaluation and treatment of RA.

Where possible, recommendations are evidence-based, resulting from a systematic literature review (SLR) as of March 19, 2018, although the clinical experience of experts and the characteristics of the Mexican health system were also considered. The evidence was classified using the GRADE system. During the second in-person session, voting took place to reach consensus, through a voting system of up to 3 rounds, considering that agreement would be reached with 80% of the votes in the first round, 75% in the second and 60% in the third. After the first and second rounds of votes, any points that had caused disagreement were discussed.

An element to consider in the Mexican health system is the non-inclusion of several indicated treatments in its basic drug tables. This limits the use of the guidelines in certain circles of care. Due to this situation, treating physicians must establish strategies based on the alternatives available at their centre. These guidelines are expected to become a benchmark in decision-making to optimise the treatment of patients with RA in Mexico.

FundingThe undertaking of these guidelines received unrestricted funding from Abbvie, Janssen, UCB and Eli-Lilly.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.