Corticosteroids are a mainstay in the therapy of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In recent years, a number of high-quality controlled clinical trials have shown their effect as a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) and a favorable safety profile in recent-onset RA. Despite this, they are more frequently used as bridge therapy while other DMARDs initiate their action than as true disease-modifying agents. Low-dose corticosteroid use during the first two years of disease slows radiologic damage and reduces the need of biologic therapy aimed at reaching a state of clinical remission in recent-onset RA. Thus, their systematic use in this clinical scenario should be considered.

Los glucocorticoides son un componente fundamental en el tratamiento de la artritis reumatoide (AR). En los últimos años, numerosos ensayos clínicos controlados de alta calidad metodológica han demostrado su acción como fármaco antirreumático modificador de enfermedad (FAME) y un favorable perfil de seguridad en la AR de reciente comienzo. No obstante, es frecuente que se utilicen más como terapia puente hasta que otros FAME comienzan a actuar que como auténticos agentes modificadores de enfermedad. Los glucocorticoides a dosis bajas durante los 2 primeros años de la enfermedad frenan el deterioro radiológico y reducen la necesidad de usar agentes biológicos para conseguir la remisión clínica en la AR de inicio por lo que se debería valorar su utilización sistemática en este contexto clínico.

Glucocorticoids (GC) were started to be used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 1948 by Hench with dramatic clinical results in patients with elevated inflammatory activity who were confined to their beds.1 Its excellent suppressive activity on joint inflammation was quickly overshadowed by the appearance of a range of side effects associated with prolonged use at medium and high doses. This prompted clinicians to relegate them to use as genuine rescue medication, to some extent, assuming treatment failure and the inability to control activity through disease modifying drugs (DMARDs) such as gold salts, antimalarials or sulfasalazine (SSZ). However, initial studies indicated2,3 that GC acted as disease-modifying drugs.

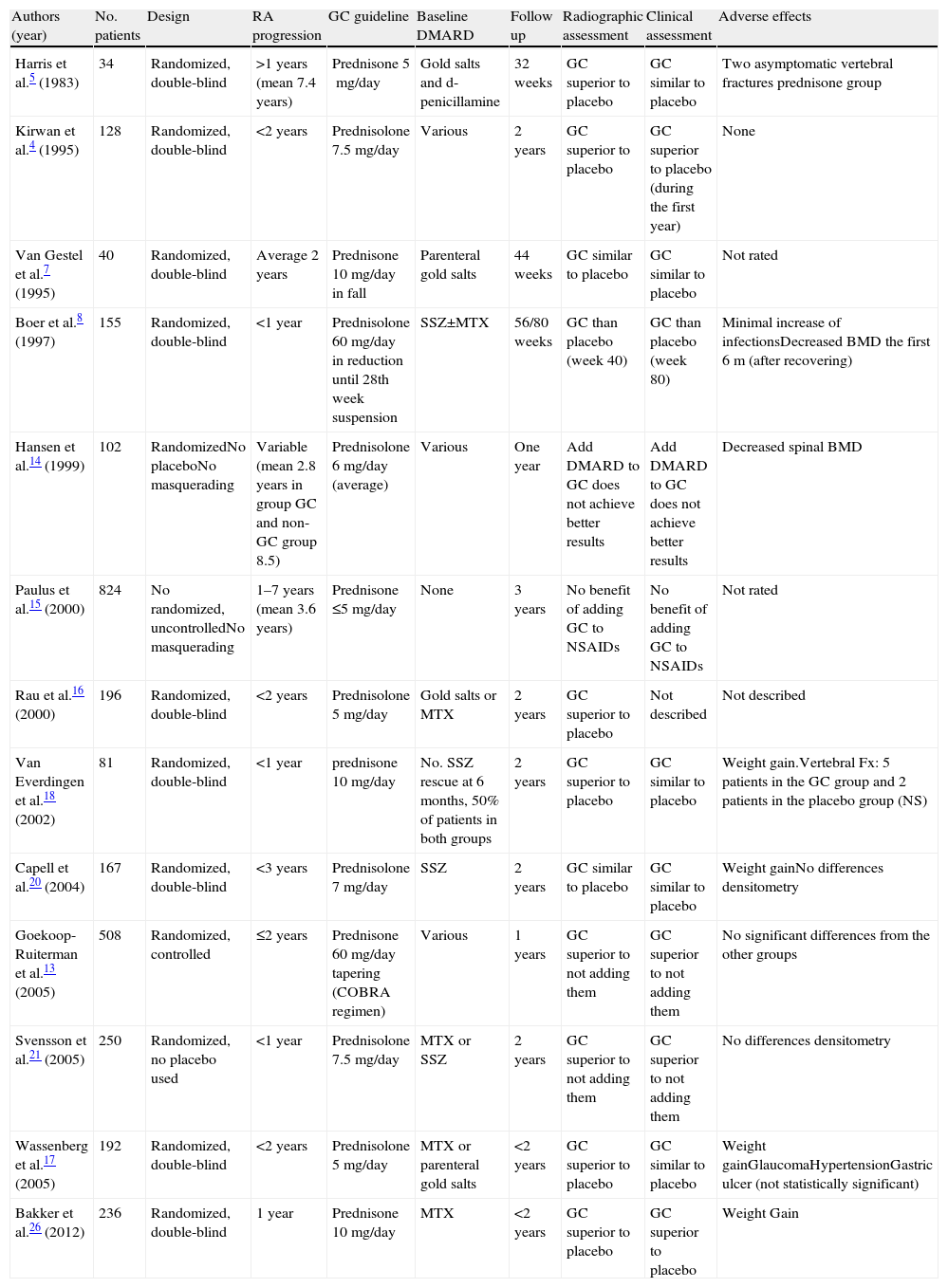

It was not until 1995 when it was hypothesized that they acted to prevent radiological damage and, ultimately, act as DMARD.4 In recent years there have been several clinical trials and meta-analysis examining the role of low dose GC in RA as DMARD and have documented their safety profile. The main features and conclusions of these randomized clinical trials are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical Trials Evaluating the Effect of Glucocorticoids in Rheumatoid Arthritis.

| Authors (year) | No. patients | Design | RA progression | GC guideline | Baseline DMARD | Follow up | Radiographic assessment | Clinical assessment | Adverse effects |

| Harris et al.5 (1983) | 34 | Randomized, double-blind | >1 years (mean 7.4 years) | Prednisone 5mg/day | Gold salts and d-penicillamine | 32 weeks | GC superior to placebo | GC similar to placebo | Two asymptomatic vertebral fractures prednisone group |

| Kirwan et al.4 (1995) | 128 | Randomized, double-blind | <2 years | Prednisolone 7.5mg/day | Various | 2 years | GC superior to placebo | GC superior to placebo (during the first year) | None |

| Van Gestel et al.7 (1995) | 40 | Randomized, double-blind | Average 2 years | Prednisone 10mg/day in fall | Parenteral gold salts | 44 weeks | GC similar to placebo | GC similar to placebo | Not rated |

| Boer et al.8 (1997) | 155 | Randomized, double-blind | <1 year | Prednisolone 60mg/day in reduction until 28th week suspension | SSZ±MTX | 56/80 weeks | GC than placebo (week 40) | GC than placebo (week 80) | Minimal increase of infectionsDecreased BMD the first 6m (after recovering) |

| Hansen et al.14 (1999) | 102 | RandomizedNo placeboNo masquerading | Variable (mean 2.8 years in group GC and non-GC group 8.5) | Prednisolone 6mg/day (average) | Various | One year | Add DMARD to GC does not achieve better results | Add DMARD to GC does not achieve better results | Decreased spinal BMD |

| Paulus et al.15 (2000) | 824 | No randomized, uncontrolledNo masquerading | 1–7 years (mean 3.6 years) | Prednisone ≤5mg/day | None | 3 years | No benefit of adding GC to NSAIDs | No benefit of adding GC to NSAIDs | Not rated |

| Rau et al.16 (2000) | 196 | Randomized, double-blind | <2 years | Prednisolone 5mg/day | Gold salts or MTX | 2 years | GC superior to placebo | Not described | Not described |

| Van Everdingen et al.18 (2002) | 81 | Randomized, double-blind | <1 year | prednisone 10mg/day | No. SSZ rescue at 6 months, 50% of patients in both groups | 2 years | GC superior to placebo | GC similar to placebo | Weight gain.Vertebral Fx: 5 patients in the GC group and 2 patients in the placebo group (NS) |

| Capell et al.20 (2004) | 167 | Randomized, double-blind | <3 years | Prednisolone 7mg/day | SSZ | 2 years | GC similar to placebo | GC similar to placebo | Weight gainNo differences densitometry |

| Goekoop-Ruiterman et al.13 (2005) | 508 | Randomized, controlled | ≤2 years | Prednisone 60mg/day tapering (COBRA regimen) | Various | 1 years | GC superior to not adding them | GC superior to not adding them | No significant differences from the other groups |

| Svensson et al.21 (2005) | 250 | Randomized, no placebo used | <1 year | Prednisolone 7.5mg/day | MTX or SSZ | 2 years | GC superior to not adding them | GC superior to not adding them | No differences densitometry |

| Wassenberg et al.17 (2005) | 192 | Randomized, double-blind | <2 years | Prednisolone 5mg/day | MTX or parenteral gold salts | <2 years | GC superior to placebo | GC similar to placebo | Weight gainGlaucomaHypertensionGastric ulcer (not statistically significant) |

| Bakker et al.26 (2012) | 236 | Randomized, double-blind | 1 year | Prednisone 10mg/day | MTX | <2 years | GC superior to placebo | GC superior to placebo | Weight Gain |

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; BMD, bone mineral density; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; GC, glucocorticoid; MTX, methotrexate; NS, not significant; SSZ, sulfasalazine.

Harris et al.5 published in 1983 the first study to suggest a possible effect of glucocorticoids on structural damage in RA. It was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial which treated 18 patients with active RA with low-dose prednisone (5mg/day) for 24 weeks, compared with 16 patients on placebo, finding at follow-up erosions in one prednisone patient group and in 4 patients in the placebo group. However, the small sample size did not enable sound conclusions.

In 1995, Kirwan4 included 128 patients with active RA of less than 2 years of evolution in a randomized, double-blind study comparing 7.5mg daily prednisolone versus placebo added to conventional DMARD therapy. The disease progressed in the first year at an average of 0.73 units in the prednisolone group, according to the Larsen radiological method, compared to 3.63 units in the placebo group (P=.052). Furthermore, the prednisolone group showed significant clinical improvement. After 2 years of follow up, only 22% of patients who had received prednisolone had radiographic erosions compared with 45% in the placebo group (P=.007). After stopping treatment with prednisolone at 2 years, it was seen that during the third6 year there was an increase of radiological damage, even though the majority of patients were receiving background treatment with DMARDs.

In contrast, Van Gestel et al.7 found no data proving that treatment with GC decreased radiological damage despite initial clinical improvement. This study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that enrolled 40 patients with RA treated with parenteral gold after the failure of other DMARDs. Twenty patients received 7.5mg of prednisone and 20 received placebo for 18 weeks. The mean duration of RA was approximately 2 years in the 2 groups.

The COBRA study compared8 RA patients of less than two years of development with poor prognostic criteria receiving a combination of SSZ, MTX and prednisolone tapering from 60mg/day to 7.5mg/day and suspension at 28 weeks –compared to SSZ monotherapy. It was observed that the rate of Sharp modified score was significantly higher in patients on SSZ at 28 weeks (P<.0001), 56 weeks (P=.004) and 80 weeks (P=.01). The lower radiological deterioration in the group whose treatment included prednisolone was maintained at 5 years of follow-up.9 Assuming that SSZ monotherapy and the combination of MTX and SSZ have a similar effect on disease progression,10 the difference between the 2 groups could plausibly be attributed to the administration of prednisolone. Van Tuyl et al.11 in 2009 published a study evaluating survival, comorbidities and structural damage after 11 years of follow-up of patients in the COBRA study.8 The authors found a significant difference of 3.1 points per year in the radiological Sharp/van der Heijde score favorable to the combined treatment group. In addition, there was a reduction in mortality in the group receiving combination therapy.

Also, an analysis of the impact of different treatment regimens from the BeSt study at 5 years follow-up has been published.12 The BeSt study13 compared the COBRA combination regimen8 with other treatment regimens (sequential monotherapy with various DMARD, stepwise addition of MTX, SSZ and HCQ and initial treatment with MTX plus infliximab) in 508 patients with RA of less 2 years. It was observed that patients who received the standard COBRA treatment or combination therapy with MTX and infliximab experienced a more rapid functional improvement and less radiographic progression at one year than patients in the sequential monotherapy or stepwise addition of conventional DMARD groups. The group that received the standard COBRA therapy showed less joint damage, probably due to a more rapid initial response than that seen in DMARD monotherapy groups or stepwise DMARD addition.

However, Hansen et al.14 in a randomized, non-blinded and non placebo-controlled study published in 1999, were unable to demonstrate superiority of prednisolone at a mean dose of 6mg daily versus not adding GC to DMARD in preventing radiographic damage after one year of treatment. It is possible that this difference in results with respect to the study of Kirwan et al.4 is due in part to the fact that it did not include patients with recent-onset RA as patients in the group receiving GC and that their RA was more recent (2.8 years versus 8.5 years in the group without GC), which may have influenced greater radiological progression rate in the group treated with GC.

In another study, published by Paulus et al.15 a post hoc analysis did not demonstrate any action of prednisone on radiological progression, although this trial was not designed specifically to study the effects of GC and RA patients included had 1–7 years of disease progression.

Instead, Rau et al.16 studied a population with RA of less than 2 years, finding significant differences in rates of radiographic damage at 6, 12 and 24 months between the two groups (with or without 5mg prednisolone daily, both with MTX or parenteral gold salts). The placebo group quadrupled the progression of the prednisolone group, mainly in the first 6 months of treatment. The authors recommended treatment with low doses of prednisolone during the first 12 months after diagnosis of RA as bridge therapy, pending the effect of DMARD. Subsequently, the same group published new results,17 this time including 192 patients (94 in the group with prednisolone 5mg/day and 98 in the placebo group) with RA of less than 2 years, treated with MTX or parenteral gold salts. The differences in radiographic progression according to the Ratingen index between the two groups were significant for the prednisolone group throughout the 24-month follow-up, although much more pronounced during the first 6 months. However, the greater clinical efficacy of GC was not sustained beyond 6 months.

In 2002 the results of placebo-controlled clinical trial by Van Everdingen et al. came to light18 which included 81 patients with RA of less than a year of development who had not previously received any DMARD. Patients were divided into two treatment groups: 41 patients received 10mg of prednisone daily and 40 received placebo for two years. It allowed the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in both groups and the initiation of SSZ, at doses of 2g/day in the first 6 months of treatment, which was introduced in the 2 groups homogeneously. The prednisone group showed greater clinical improvement in nearly all measured variables (mainly endpoints of the disease by the patient) but this difference was not maintained past six months except with respect to the tender joint count and prensile strength. The radiographic progression was significantly lower in the prednisone group and this difference persisted at 2 years, with an Sharp index score of 16±23 in the prednisone group versus 29±26 in the placebo group (P=.007). In the opinion of the authors, the discrepancy between the clinical and radiological results could probably be attributed to the increased use of complementary therapies and the placebo group. In the 5 year follow-up study,19 (2–3 years after stopping treatment) there was less radiological progression in the prednisone group compared with the placebo group, both in total score radiological Sharp/van der Heijde index (P=.01) and joint impingement score (P=.02), There were no differences in clinical variables or the use and duration of FAME.

The study by Capell et al.20 showed no significant differences in GC in preventing radiographic damage. This randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial included 167 patients with RA of less than 3 years treated with SSZ randomized to receive a 7mg prednisolone daily (84 patients) or placebo (83 patients) for 2 years. 59% of patients with erosions in the placebo group and 61% in the prednisolone group had radiographic progression, with no differences between the 2 groups in any of the radiological variables. No significant differences were seen in terms of clinical efficacy. These results contrast sharply with those obtained by other authors.4,16,18 Differences between the groups (genetic and the percentage of patients with erosive disease), the systematic use of SSZ as DMARD and the different methods used to quantify radiological damage could explain this discrepancy.

Svensson et al.21 selected 250 patients with active RA of less than one year of evolution, randomizing 119 to 7.5mg/day of prednisolone and 131 to no treatment or placebo. All patients received a DMARD at the discretion of their doctor, mainly MTX or SSZ. The change in the overall radiographic score according to the index of Sharp/van der Heijde was less p ronunciado in the prednisolone group as both a year to two years, with significant differences between groups. The erosion rate was also significantly lower in the prednisolone group and a similar trend, but no statistical significance, was seen in joint impingement scores. With regard to clinical efficacy, measured through DAS28, significant differences were found for the prednisolone group starting at 3 months of treatment, and these differences were maintained over a 2 year follow up.

In 1997 the first meta-analysis was published,22 which included nine studies on the use of GC, with a total of 472 patients with RA. A first analysis compared the efficacy of prednisone at a mean dose of 10.2mg/day versus placebo, aspirin, chloroquine and deflazacort. In the second, prednisone was compared against various DMARD, among which MTX, SSZ, hydroxychloroquine, and parenteral gold salts were employed. Prednisone r proved superior to placebo and about as effective as conventional DMARD with regard to clinical and laboratory parameters. The radiological progression was not formally studied by the great disparity in the assessment of radiographic progression between studies.

In 2010, another meta-analysis was published23 which attempted to define the differences in joint damage between different treatment strategies: DMARD monotherapy, combination therapy plus DMARD and GC, GC monotherapy and biological agents. They analyzed data from 70 trials and compared with placebo and the annual radiological progression rate. It was evident that all groups in the first year reduced the rate of progression by 48%–84%. Compared with the monotherapy group, the annual radiological progression rate was 0.62% lower in the group of 2 DMARD plus GC (P<.001) and 0.61% lower in the biological plus MTX group (P<.00001). The authors proposed reserving the biological agents for patients who do not respond to combination therapy. They also recommended future trials that directly compared treatment with a biologic agent plus one DMARD with 2 or 3 DMARD and GC.

A review from the Cochrane Library,24 2006, that took into account only studies with low-dose GC compared with placebo or NSAIDs and short-term follow-up, concluded that doses equivalent to or less than 15mg prednisolone were highly effective in daily clinical management of RA. This analysis excluded most of the abovementioned studies because of its long term monitoring.

A subsequent meta-analysis of the Cochrane Library25 on the effectiveness of corticosteroids for inhibiting the progression of radiological damage identified 15 randomized controlled trials that included 1414 patients with RA, mostly early cases, in comparing GC and placebo to no treatment. In most cases, GC was used added to a standard regimen of conventional DMARD. Hands and feet radiographs were evaluated and the difference in radiological progression was significant in all studies except one. This meta-analysis provides strong evidence in favor of the role of GC as a DMARD in RA of less than 2 years of evolution and added to a conventional DMARD.

Finally, the results of the CAMERA II study,26 a randomized, placebo-controlled trial directly comparing treatment with MTX plus 10mg/day of prednisone versus placebo and MTX and within a protocol escalation and treatment dose adjusted to a preset target with therapeutic intensification has to be considered. In the MTX+GC group, 78% of patients had no erosions at 2 years follow-up compared with 67% in the other group (P=.022) and radiographic damage score according to the radiological Sharp/van der Heijde index was 0.87 units lower in the prednisone group (P=.001). This group also had a better and faster clinical response, including functional capacity and quality of life. Another fact of great pharmacoeconomic significance was that only 20% of patients treated with MTX+GC versus 40% of those treated with placebo MTX+placebo needed to add an anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agent to achieve good control of the disease, and this difference was statistically significant (P<.001).

In summary, the addition of low doses of GC to conventional DMARD, ideally MTX, in RA of less than 2 years of evolution has shown solidly to slow radiological progression, improve symptoms and signs of the disease, improving the functional prognosis of patients and reduce the need for maintaining biological therapy for patients with clinically adequate control of the disease.

Safety of Glucocorticoids in Rheumatoid ArthritisAfter more than 60 years of experience, the extent of the risk of major adverse events (AE) associated with the use of GC treatment regimen depends on how likely the use of GC is present and if this long-term risk remains despite their suspension has not been fully clarified. There is still mistrust of their side effects by physicians and patients, although controlled studies discussed above have revealed an exceptionally favorable safety profile. In addition, assessment of patient characteristics, underlying disease, comorbidities present, the dose and time are used to define this risk individually.

Hoes et al.27 in a meta-analysis, showed that in RA the risk of AE due to the use of GC is significantly lower (43 AE of 100 patient-years) than in polymyalgia rheumatica (88 AE per 100 patient-years) or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (550 AE per 100 patient-years). These results seem to influence not only the study design (in most RA study designs AE frequency is not collected in a systematic way unlike IBD), but also the characteristics of the study population. In RA it is known that most AE related to GC occur at high doses and occur less frequently in the long-term. In the meta-analysis that quantified the risk of AE with low and medium doses of GC from the first month of treatment continued having a low risk, confirming the good safety profile of short-term low-dose GC treatment described in previous studies.4 The most common AEs found were mild psychological or behavior disorders followed by minor gastrointestinal problems such as dyspepsia.

In an 11-year follow-up study of COBRA8 major AE attributed to the use of GC were hypertension, hyperglycemia and cataracts (P=.02). However, in the group treated with GC, hypercholesterolemia, cancer and infections were less frequent. In addition, patients treated with GC did not show an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease or osteoporosis. In fact, treatment of the disease, reducing inflammatory activity could reverse the altered lipid profile, acting as a cardioprotective agent.28

Another meta-analysis published in 2009,29 also found a favorable balance between the expected benefit and the risk of AE associated with the use of low-dose long-term GC-over a year-in RA. The same conclusions can be drawn from the BeST study after 5 years of follow up,12 with no evidence to start GC combination therapy, increased the risk of long-term toxicity, and mortality remained similar for all AE in the treatment groups.

CAMERA II26 even found beneficial effects in the MTX+GC group, with less nausea and less alteration of liver enzymes, e.g. However, it found greater weight gain and higher blood glucose levels after 2 years of treatment attributable to the use of GC. A slight weight gain is common, even with low doses of GC, but is usually reversible after discontinuation.8,17,18,20

Another major concern about the chronic use of GC is the increased susceptibility to infections. The risk of infection increases with the dose and duration of treatment and is discrete in patients using low doses, even when the cumulative dose is higher.30 A meta-analysis of 71 studies,31 which included 2111 patients with different conditions and different doses of GC, found that the relative risk of infection was 2. However, the 5 studies that included patients with rheumatic diseases with GC identified, did not find a significantly elevated risk of infection, even in the subgroup of patients treated with doses below 20mg/day of prednisone, regardless of the process by which GC were indicated.

However, Dixon et al.32 using a model in which he used the cumulative dose of GC, found a history of GC consumption in a population of RA patients over 65 that also increased the risk of infection in the 2–3 years after the suspension, although the risk was much higher if GC consumption was current or within the prior 6 months. Of 16207 patients, 1947 developed a serious infection in a follow-up of 3.8 years. The authors calculated that current use of 5mg of prednisolone continuously conferred an increased risk of serious infection of 30%, 46%, and 100% by the third and sixth months and third year, respectively. Obviously, we cannot rule out prescription bias for glucocorticoids in patients with more aggressive RA despite conventional treatment, since the inflammatory activity of RA has also been implicated as a factor favoring the development of infections.

Various studies on the occurrence of fractures in osteoporosis due to corticosteroids have suggested that risk is determined by several factors, including bone mineral density (BMD) before and after treatment, the dose of GC, the duration of treatment, underlying disease, the risk of falls and, finally, bone strength, since it has been observed that patients receiving GC have fractures with higher values of BMD.33–36 Of all these factors, the most compared are the dose and duration of treatment, although no consensus has been reached on the dose that is considered safe. A subgroup of 24 patients included in the study by Kirwan4 underwent annual BMD measurement of the lumbar spine and femoral neck. Although the prednisolone group lost more bone mass in the lumbar spine during the first year of treatment, the difference with the placebo group was offset during the second year and in the end there was no significant difference.37 In the same vein, a review38 by Verhoeven and Boers concluded that bone loss occurred early in the course of treatment with low doses of GC but stabilized over time in patients receiving prolonged therapy and even reverted after discontinuation. These findings suggest that the initial detrimental effect of GC on bone remodeling would be offset by a significant reduction of the inflammatory burden, even protecting the bone.21,30 It is necessary to note that RA activity leads to a reduction in physical activity and a significant elevation of inflammatory cytokines that stimulate the differentiation of osteoclasts. Therefore, the reduction of the inflammatory burden reduces bone mass loss.30,33

Hyperglycemia may occur relatively quickly after the start of treatment with GC. With daily doses below 8mg of prednisone, the risk of hyperglycemia is 1.77 (95% CI, 1.54–2.02) and increases with the dose of GC used, becoming 10, 34 (95% CI, 3.16–33.90) for doses higher than 25mg of prednisone daily.39 Patients who have risk factors for developing diabetes, such as obesity or family history, have an increased risk of hyperglycemia during treatment with GC.28 Fortunately, the emergence of frank diabetes with low-dose glucocorticoids is rare.33

The side effects of low dose GC documented by different studies are much less frequent than those seen with high doses of GC. If one also takes into account the indication bias, it is likely that complications directly related to the use of low-dose GC are even less frequent. It should be emphasized that patients with more severe disease and more comorbidities are more likely to receive GC treatment than well controlled RA patients, so that the allocation of certain adverse events due to the use of GC in nonrandomized observational studies is questionable from a methodological point of view.

ConclusionsThere is solid evidence generated in clinical trials of high methodological quality that low-dose glucocorticoids have a modifying effect of structural damage in early RA. This is probably because GC inhibit cytokine production induced by factor receptor-ligand κβ that activate osteoclasts.

No studies have evaluated whether the protective effect is maintained after 2 years of continuous use. However, there is evidence that the improvement produced in early RA impacts outcome after 10 years of follow up. The recommendation would be to interrupt them at 2 years.40 Moreover, glucocorticoids also have shown effectiveness as bridge therapy.40

Our recommendation is to start early treatment with MTX and an increasing pattern of low dose GC during the first 2 years of the disease, as postulated by the latest EULAR guidelines41 in the treatment of RA. Toxicity has not proven higher than that of other DMARDs and its use at low doses during the first 2 years of the disease seems reasonably secure, partly due to the benefits caused by the control of the inflammatory activity and its impact on bone and lipid metabolism. Therefore, GC should be positioned next to adequately scaled MTX as a cornerstone in the treatment of recent-onset RA, following the endorsement of firm and high quality scientific evidence. Optimal doses, decrease patterns and the time of administration and the efficacy of long-term use are not precisely known.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this research has not been done in humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors state that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: García-Magallón B, et al. Actualización del uso de los glucocorticoides en la artritis reumatoide. Reumatol Clin. 2013;9:297–302.