Osteoporosis (OP) and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) share pathophysiological mechanisms and risk factors. The severity of OP correlates with cardiovascular (CV) risk, suggesting the need for integrated clinical approaches. The VASOS study aimed to have an approach to the frequency of comorbidities, especially CVD, and cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), in OP patients in Spain within a Rheumatology setting, assessing their possible impact on OP treatment decisions.

Materials and methodsSpanish survey-based multicentre study involving 62 Spanish rheumatologists, which give information from the last 10 patients. Participants were selected according to their clinical expertise and their geographical area. Questions were oriented to describe the profile of patients (OP and CVRF), and prescription habits. “Influence on treatment choice” was only accounted if the presence of one or more CVRF could affect the selection of the OP treatment.

ResultsData from 620 patients were collected. The patients were predominantly women (85.2%) with primary OP (73.2%). Bisphosphonates, denosumab and teriparatide were the most used treatments. Most common comorbidities included inflammatory rheumatic or autoimmune diseases, endocrinopathies and major CVD. CVRF influenced treatment choice for 82.3% of rheumatologists, who often avoided prescribing romosozumab, selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), and menopausal hormone therapy (MHT).

ConclusionsMost patients with OP are women with primary OP, often having CVRF. Oral bisphosphonates, denosumab, and teriparatide are the preferred treatments, avoiding MHT, SERMs, and romosozumab in patients with CVRF.

La osteoporosis (OP) y las enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) comparten mecanismos fisiopatológicos y factores de riesgo. El estudio VASOS tuvo como objetivo establecer una aproximación a la frecuencia de comorbilidades, especialmente ECV, y factores de riesgo cardiovascular (FRCV), en pacientes con OP en España en un entorno reumatológico, evaluando su posible impacto en las decisiones de tratamiento de la OP.

Materiales y métodosEstudio multicéntrico a partir de una encuesta en la que participaron 62 reumatólogos españoles que ofrecieron información a partir de sus últimos 10 pacientes con OP. Los participantes se seleccionaron de acuerdo con su experiencia clínica y su área geográfica. Las preguntas estaban orientadas a describir el perfil de los pacientes (OP y FRCV) y los hábitos de prescripción. «Influencia en la selección del tratamiento» solo se consideró si la presencia de uno o más FRCV podía afectar la elección del tratamiento de la OP.

ResultadosSe recogieron datos de 620 pacientes, predominantemente mujeres (85,2%) con OP primaria (73,2%). Los bifosfonatos orales, el denosumab y la teriparatida eran los tratamientos más empleados. Las comorbilidades más frecuentes eran las enfermedades inflamatorias, reumáticas o autoinmunes, las endocrinopatías y las ECV mayores. Los FRCV influyeron en la elección del tratamiento en el 82,3% de los reumatólogos, que evitaban prescribir romosozumab, moduladores selectivos de los receptores estrogénicos (SERM) y terapia hormonal para la menopausia (THM).

ConclusionesLa mayoría de los pacientes con OP son mujeres con OP primaria, que con frecuencia presentan FRCV. Los bifosfonatos orales, el denosumab y la teriparatida son los tratamientos preferidos, evitando la THM, los SERM y el romosozumab en pacientes con FRCV.

Osteoporosis (OP) is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by reduced bone mineral density (BMD) and deterioration of bone microarchitecture. OP is estimated to affect over 200 million people worldwide, with one in three women and one in six men likely to suffer the disease during their lifetime.1 OP is a chronic condition which significantly increases bone fragility and susceptibility to fractures from minimal trauma and it is influenced by a complex interplay of biological factors including age, gender, genetics, environmental factors, and lifestyle.2 OP is considered a global public health problem, contributing to decreased quality of life, increased disability and institutionalization, higher mortality and morbidity rates, and substantial healthcare costs. In 2019, the total cost of fragility fractures and pharmacological interventions in Europe was estimated at 56.9 billion euros, representing about 3.5% of the healthcare spending. The total costs and the percentage of healthcare spending increase every year.1

Several studies analysed the relationship between OP and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs),3–9 the leading cause of death.10 Both conditions share common pathophysiological mechanisms regulating bone homeostasis and vascular repair, involving factors like type 1 collagen, proteoglycan, osteopontin, osteonectin, bone morphogenetic proteins, osteoprotegerin, RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand), phosphate, parathyroid hormone, and vitamins D and K.4,5 Some of the risk factors for both CVD and OP are also shared, with advanced age as a particularly critical factor, but also including family history, oestrogen levels, dyslipidaemia, oxidative stress, inflammation, hypertension, hyperhomocysteinemia, hypovitaminosis D, diabetes mellitus, glucocorticoid intake, and lifestyle factors.4,5

The connection between these conditions might be related to the dependence of skeletal and muscle function on vascular health for blood and nutrient supply, which can be compromised by CVD.4–6 Clinical studies have shown associations between vascular calcification or CVD events and OP, reduced BMD or fracture. For instance, studies have shown that major cardiovascular (CV) events are more common in postmenopausal women with lower BMD.6,11 Similarly, decreased BMD is a predictor of the risk of atherosclerotic vascular disease (AVD),7 with AVD more frequently present in women with OP.12 Moreover, women with low BMD have a 1.9-fold increased risk of stroke,3 and men with OP are at increased risk of CV mortality, whereas women are more prone to CV events but not necessarily CV death.9 Nevertheless, there is a proportional relationship between the severity of OP and the risk of CV events.11 On the other hand, in postmenopausal women, the presence of AVD contributes to the risk of development of OP and hip fractures.13 In this line, a meta-analysis of eight observational studies also linked heart failure with an increased risk of fractures.8 Preliminary studies indicate that some OP treatments may positively impact the CV system.5

Despite the overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms and risk factors between OP and CVD, along with the established scientific evidence linking these conditions, there are very few data analysing the frequency of CVD or CV risk factors in OP patients in clinical practice, or investigating if the presence of these conditions influences the therapeutic management.

The aim of the VASOS (cardioVAScular risk in patients with OSteoporosis) study was to analyse the frequency of comorbidities, with special focus on CVD, as well as the frequency of CV risk factors (CVRF) in patients with OP in Spain in a Rheumatology setting, and if it could influence the osteoporosis therapeutic management of patients.

Material and methodsStudy design and populationVASOS was a Spanish multicentre survey-based study, where the data source was from the insights of rheumatologists in a real clinical setting. No data were collected from patient's medical records. The selection of participants was based on their expertise in OP management and on their geographic area, to have a representative sample, with different clinical experience and including rheumatologists from hospitals throughout various regions of Spain (Autonomous Communities).

All the participants received a remuneration from the sponsor after completing the survey.

Survey and data collectionA total of 62 rheumatologists completed an online survey during the period between January and April of 2023. The participants are listed in the Appendix.

After been provided with a leaflet outlining the aims of the study and agreeing to participate, all physicians were given a link to access the survey. The survey consisted of 25 questions in two sections: the first six questions aimed to identify the characteristics of the participants, while the remaining 19 focused on their experiences with their last 10 patients with OP. These 19 questions were oriented to describe the profile of patients, OP and CVRF, the treatment for OP and the prescription habits. “Influence on treatment choice” was only accounted when participants considered that the presence of one or more CVRF could affect the selection of the osteoporosis treatment.

Completion of the survey required answers to all questions. To prevent potential biases in participants’ responses, surveys were anonymised. The CROSS guidelines were used to report on the findings.

Ethics statementAll procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain), with code 23/023-E. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants (rheumatologists) included in the study. For this type of study, patient consent is not required, as there was no extraction of data from the medical records of patients and all treatments were administered according to routine clinical practice.

Statistical considerationsA descriptive analysis of the answers was performed. For qualitative questions, absolute frequencies were calculated, and for quantitative questions, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were computed. In cases of multiple-choice questions, the sum of percentages could exceed 100%.

The statistical analyses were performed with R, version 4.2.1.

ResultsRheumatologists profileSixty-two rheumatologists completed the survey, with a mean age (SD) of 43.8 years (11.3). Six out of ten (59.7%) were women. In terms of experience treating patients with OP, 51.6% had over 10 years of experience. The majority (82.3%) saw between 10 and 40 patients with OP each week (Table 1). Most of the consultations (93.5%) took place in public hospitals from different regions in Spain (Appendix).

Patient characteristicsRegarding the last 10 patients with OP attended by the rheumatologists (global population of 620 patients), around half (51.4%) were between 66 and 80 years old, while 23.2%, were over 80 years old. Most of these patients were women (85.2%). OP diagnosis was recent (in the last five years) in 45.7% of patients, while in 20.7% of cases OP was diagnosed more than 10 years ago. Most of the patients (mean of 73.2%) had primary OP, and the most common comorbidities were inflammatory rheumatic or autoimmune diseases (26.9%), endocrinopathies (26.7%), and major CVD (16.9%) (Table 2).

Patient characteristics.

| Mean, % (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <50 years | 3.9 (4.3) |

| 50–65 years | 21.5 (11.9) |

| 66–80 years | 51.4 (15.5) |

| >80 years | 23.2 (17.6) |

| Sex | |

| Men | 14.8 (12.3) |

| Women | 85.2 (12.3) |

| Time since diagnosis | |

| <5 years | 45.7 (26.5) |

| 5–10 years | 33.7 (19.6) |

| 11–20 years | 14.7 (11.3) |

| >20 years | 6.0 (12.3) |

| Type of osteoporosis | |

| Primarya | 73.2 (17.7) |

| Secondary | 26.8 (17.7) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Inflammatory or autoimmune rheumatic diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, spondylarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) | 26.9 (17.8) |

| Endocrinopathies (type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism) | 26.7 (17.8) |

| Major cardiovascular diseases (stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure) | 16.9 (16.3) |

| Respiratory diseases (asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) | 16.2 (12.5) |

| Depression | 14.9 (14.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11.5 (11.2) |

| Neoplasms | 10.1 (11.5) |

| Cognitive impairment or dementia | 6.7 (10.7) |

| Intestinal malabsorption (celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease) | 4 (5.5) |

| Haematological diseases (multiple myeloma, monoclonal gammopathy, leukaemia, lymphoma, amyloidosis, mastocytosis, haemoglobinopathies) | 3.8 (5.1) |

| Chronic liver disease | 3 (5.1) |

| Transplants (liver, kidney, lung, or heart) | 1.7 (5.5) |

| Eating disorders (anorexia nervosa) | 1.3 (2.6) |

| Otherb | 1.3 (5.9) |

| Previous fractures | 53.8 (24.2) |

| Fracture location | |

| Vertebral | 37.5 (19.5) |

| Hip | 16.7 (17.9) |

| Wrist (distal radius) | 14.3 (13.2) |

| Humerus | 5.6 (7.4) |

| Other fractures | 2.5 (4.2) |

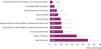

The rheumatologists taking part in the study indicated that a mean (SD) of 53.8% (24.2) of the patients had suffered one or more fragility fractures. Vertebral fractures were the most common (37.5% of the patients), followed by hip fractures (16.7%). When asked for the main risk factors for OP and fragility fracture, most of participants identified older age (68.4%) and previous fracture (47.9%), followed by the use of glucocorticoids (23.4%) (Fig. 1).

Focusing on CVD, according to the participants the most frequent conditions were heart failure and ischemic heart disease, present in a mean of 11.2% and 11.1% of the patients, respectively (Fig. 2a). A mean (SD) of 65.1% (20.1) of the patients had at least one CVRF. The most common CVRF was sedentary lifestyle, present in a mean of 39% of the patients (Fig. 2b).

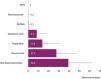

OP treatmentWhen asked about the treatments prescribed, the rheumatologists indicated that a mean (SD) of 73% (25.5) of the patients were receiving a specific treatment for OP (antiresorptive or bone forming agent), while 64.5% (29.8) had received previous OP treatments. The most common current and previous OP treatments were oral bisphosphonates followed by denosumab, teriparatide and zoledronic acid. The order of preference for the OP treatment in patients with some CVRF did not change, being oral bisphosphonates the first choice, followed by denosumab, teriparatide and zoledronic acid (Fig. 3). However, according to the participants, the prescription of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or romosozumab was marginal.

The presence of CVRF was considered by 82.3% of the rheumatologists when selecting the OP treatment, mainly avoiding the prescription of romosozumab, SERMs and MHT (Fig. 4). In addition, most of the rheumatologists (66.1%) reported that they offer guidance and counselling on maintaining a healthy lifestyle in patients with CVRF. On the other hand, 19.4% of them prescribe and monitor CV treatments, while 14.5% delegate the management of CVRF to the Primary care physician.

Finally, 98.4% of rheumatologists believe that there is a need for more training or education on CV risk in OP.

DiscussionThe VASOS study described the rheumatologist's perception regarding the frequency of comorbidities, CVD and CVRF in patients with OP, and the influence on their OP patient management. To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in real clinical practice that provides an approximation of the frequency of CVD and CVRF in patients with OP within a Rheumatology setting.

According to the participants, almost 75% of the patients with OP were aged 65 or above. It is well known that the prevalence of OP increases with age.14 Also, aging predispose to CVD, and it is associated with both structural and functional disturbances on the CV system.15 The predominance of women in the VASOS study is also aligned with the female dominance in OP.16 The rheumatologists participating in the study identified age as the most frequent risk factor for OP and fragility fracture, while a sedentary lifestyle was the most frequent CVRF, closely followed by dyslipidaemia and high blood pressure. Although age and sex are non-modifiable risk factors, modifiable lifestyle choices such as physical activity, dietary habits, smoking, and alcohol consumption play a significant role in the onset and prevention of both OP and CVD.17

Inflammatory rheumatic or autoimmune diseases, along with endocrinopathies, were the most frequent comorbidities in patients with OP. As the study was conducted in Rheumatology units, an increased occurrence of rheumatic and autoimmune diseases was anticipated. Patients with rheumatic diseases are more susceptible for OP due to the bone-degrading effects of both inflammation and corticosteroid treatment.18 Moreover, the reduced physical activity often associated with rheumatic diseases may lead to lower mechanical loading on bones, which is essential for preserving BMD and strength.18 Hormonal imbalances, whether a deficiency or excess, can occur in these patients, and can lead to BMD loss.19

Surprisingly, rheumatologists reported that only an average of 15% of patients experienced depression, lower than what has been previously reported, where the majority of patients with OP exhibited mild to moderate depression.20 This discrepancy might be due to patients not reporting depressive symptoms or the limited time available during medical consultations for a comprehensive evaluation of mental health.

According to the participants, one out of six OP patients had a major CVD. It is well known that OP and CVD share overlapping pathophysiological processes and risk factors.4,5 The most prevalent CVDs among patients with OP were heart failure and ischemic heart disease. Heart failure has been linked to a rise in major osteoporotic fractures.8 Various theories have been suggested to explain the relationship between OP and heart failure, such as chronic inflammation and the overstimulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.21 Similarly, patients with ischemic heart disease are at an increased risk of fractures due to shared pathophysiological processes, which involve factors that contribute to the formation of calcified vascular plaque and bone turnover.22

The rheumatologists participating in the study indicated that they took CVRF into account before prescribing OP treatments. Patients identified with CVRF were not administered MHT, and the average percentage of patients treated with SERMs and romosozumab was numerically reduced from 0.7 and 1.1 to 0.3 and 0.2 respectively, compared to all patients with OP. Furthermore, the rheumatologists expressed that they tend to avoid these treatments in patients with CVRF.

Some therapies for OP may confer CV benefits.5 Several studies conducted on women with OP suggested that bisphosphonates might protect against atherosclerosis by slowing the progression of calcification in the abdominal aorta, decreasing the thickness of the carotid artery walls, and improving patients’ cholesterol levels.23,24 Despite these findings, a meta-analysis encompassing 58 randomized clinical trials found no substantial link between bisphosphonate use and a reduction in CV events.25 On the other hand, SERMs like raloxifene and bazedoxifene have been linked to an increased risk of venous thromboembolism,26,27 MHT has been found to increase CVD by 22%,28 and the CV profile of romosozumab is unclear.29 Therefore, the presence of CVRF must be meticulously assessed before initiating any OP treatment.16 There is not concern about the CV risk with teriparatide or denosumab, and this is reflected in our results, with the prescription of this drugs not been affected by the presence of CVRF. Although abaloparatide was not commercialized in Spain when the study was conducted, according to a real-world study from US, it seems its cardiovascular profile could be comparable to teriparatide.30

According to most of the participants, there is a need for increased training or education on CV risk and OP. This call to action could improve the knowledge of the link between the two diseases and could impact in a better patient management.

This study had several limitations. The data collected were from the insights of rheumatologists, which could be subject to recall bias and lack of individual patient data. Another limitation is that the study was carried in a Rheumatology setting in Spain, so the results may not be applicable or representative of other settings or countries.

Nonetheless, this study offers a novel insight into the intersection of OP and CVD, highlighting the importance of holistic patient care and the need for further investigation into the interplay of OP, CVD, and associated risk factors. Future research could focus on refining strategies to assess CVRF while determining the most suitable OP treatment for each patient.

ConclusionIn conclusion, the VASOS study provides a survey-based comprehensive characterization of patients with OP in a Rheumatology setting in Spain. Most of these patients seem to be elderly women, with primary OP. However, comorbidities such as inflammatory, endocrine, and CVD are common, with CVRF being present in over half of the patients. In patients with CVRF there is a preference for oral bisphosphonates, followed by denosumab and teriparatide, avoiding the use of MHT, SERMs and romosozumab. This study highlights the need for enhanced education on CV risk to improve the management of OP patients.

FundingThis work was funded by Grünenthal Pharma S.A. Medical writing support provided by Evidenze Health España S.L.U., was funded by Grünenthal Pharma S.A.

Conflict of interestE. Casado has received funding for travel or speaker fees from Amgen, UCB, Theramex, STADA, Gedeon-Richter, Grünenthal and GP-Pharm.

I. Gómez-Olmedo is an employee of Grünenthal Pharma.

The list of participants conforming the VASOS study group is provided in the Appendix.

Medical writing support was provided by Carmela García Doval at Evidenze Health España S.L.U. during the preparation of this paper. Responsibility for opinions, conclusions and interpretation of data lies with the author.

| Autonomous Community | Participant |

|---|---|

| Andalusia | Laura Bautista Aguilar |

| Ana de Vicente Delmas | |

| Lola Fernández de la Fuente | |

| Wenceslao Hernanz Mediano | |

| Francisco Gabriel Jimenez Núñez | |

| Gonzalo María Jurado Quijano | |

| Mar López-Sidro Ibáñez | |

| Mª Dolores Miranda García | |

| María Priego | |

| Rodrigo Ramos Morell | |

| Antonio Romero Pérez | |

| Aragon | Juan Carlos Cobeta García |

| Marina Soledad Moreno García | |

| Asturias | Manuel Rubén Queiro Silva |

| Balearic Islands | Carolina Bordoy Ferrer |

| Inmaculada Ros Vilamajó | |

| Basque Country | César Antonio Egües Dubuc |

| Marta González Fernández | |

| Canary Islands | María Jesús Montesa Cabrera |

| Fayna Perdomo Herrera | |

| Cantabria | Natalia Palmou Fontana |

| Castile-La Mancha | Ginés Sánchez Nievas |

| Castile and Leon | Montserrat Corteguera Coro |

| Ismael González Fernández | |

| Juan Pablo Guzmán | |

| Alejandra López Robles | |

| José Andrés Lorenzo Martín | |

| Guadalupe Manzano Canabal | |

| Cristina Parraga Prieto | |

| Catalonia | Gabriel de Febrer Martínez |

| Noemi Navarro Ricos | |

| María Pascual Pastor | |

| Milagros Ricse Salcedo | |

| Basilio Rodríguez Díez | |

| Marta Valls Roc | |

| Extremadura | Mª Carmen Carrasco Cubero |

| Galicia | Antonio Domingo Atanes Sandoval |

| Luis Fernández Domínguez | |

| Nair Pérez Gómez | |

| Victor Eliseo Quevedo Vila | |

| Alejandro Souto Vilas | |

| La Rioja | Miguel Medina Malone |

| Madrid (Community of) | Ángel Aragón Díez |

| Celia Arconada López | |

| Alberto Díaz Oca | |

| Mónica Fernández | |

| Fernando Lozano Morillo | |

| Irene Monjo Henry | |

| Atusa Movasat Hajkhan | |

| Marina Salido Olivares | |

| Cristina Valero Martínez | |

| Murcia (Region of) | Esther Fernández Guill |

| Deseada Palma Sánchez | |

| Navarre | María Cruz Laíño Piñeiro |

| Valencian Community | Pablo Andújar Brazal |

| Nerea Costas Torrijo | |

| Marta Garijo Bufort | |

| Juan Miguel López Gómez | |

| Adrián Mayo Juanatey | |

| Clara Molina Almela | |

| Gaspar Panadero Tendero | |

| María José Pozuelo |