Keloidal or nodular scleroderma (NS) is a variant of localized scleroderma (LS) frequently seen in patients with limited or diffuse systemic sclerosis (SSc). It presents as raised, firm plaques or nodules with extensive dermal fibrosis and hyalinized collagen bundles. We present a patient with SSc who presented with this rare entity.

La esclerodermia nodular o queloidea es una variante de esclerodermia localizada que se encuentra predominantemente en pacientes con esclerosis sistémica limitada o difusa (SSc). La presentación clínica es de placas o nódulos firmes y sobreelevados con fibrosis dérmica y haces de colágeno hialinizados. En este reporte de caso presentamos a una paciente con SSc con esta entidad rara.

LS is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by single or multiple sclerotic plaques in the skin and subjacent tissues. It is distinct from SSc, an autoimmune disease in which diffuse cutaneous sclerosis is accompanied by systemic manifestations.1

According to the classification proposed by Kreuter and upheld by the European Dermatology Society, LS has five phenotypic variants: plaque, generalized, bullous, linear, and deep.2,3 NS is a rare variant characterized by sclerotic lesions that rise above the surrounding skin.

We describe a 27-year-old female with a history of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (lcSSc) presenting with multiple keloidal nodules.

Case reportA 27-year-old Hispanic female with a medical history of lcSSc presented for the evaluation of multiple hyperpigmented nodules in her skin. She was diagnosed with lcSSc five years earlier after developing sclerodactyly, Raynaud's phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, and positive anti-centromere antibodies. Shortly after, she developed multiple asymptomatic nodules on her thorax, slowly increasing in size and number. There was no history of trauma or surgery in any affected site and no personal or family history of keloid formation.

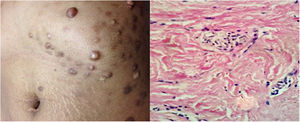

Physical examinations revealed classic findings of lcSSc: sclerodactyly, telangiectasias, fingertip scars, and characteristic facies. Additionally, she presented multiple (25–30), non-tender, firm, hyperpigmented, well-circumscribed nodules scattered on the chest and back; the largest lesion was 4.5cm in diameter (Fig. 1). Some nodules appeared within areas of sclerotic skin changes, and others in normal skin.

An excisional biopsy of a nodule in the back revealed dermal fibrosis with haphazardly arranged thickened and compact collagen bundles with loss of interfibrillar space, sclerotic appearance, and loss of adnexal structures. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of NS.

DiscussionIn 1854, Addison first described firm, nodular elevations in sclerodermatous skin.4 Over the next century, this entity received different names: “keloid-like scleroderma”, “tuberous morphea”, and “fibromes miliares folliculaires, sclérodermie consécutve”. In 1960 Cabré and Landes concluded that flat nodules and keloid-like plaques were part of the same spectrum and rendered the terms nodular and keloidal scleroderma interchangeable.5

There are only a few cases of NS published to date,6,7 and like this case, most occur in individuals with a diagnosis of lcSSc. In clinical practice, the association of LS with lcSSc is an unusual observation, and the idea that the first may progress to the latter has been abandoned.8

Soma et al. observed LS in 9 out of 135 patients with lcSSc and found that male gender and a negative antinuclear antibody, two very unusual features in lcSSc, were significantly correlated with this association.9 Some authors have argued that cases of concurrent LS and lcSSc and patients that report progression may be lcSSc mistakenly identified as LS or vice versa.10 Hence, it is remarkable that most cases of NS, a condition considered a rare form of LS, have been described in patients with lcSSc.

The spectrum of histopathologic findings in NS comprises 1. Keloid (hyalinized collagen bundles), 2. Scleroderma (dermal horizontal sclerotic bands), and 3. Mixed findings,7 such as this case. The main differential diagnoses include keloid/hypertrophic scar, storiform collagenoma, sclerotic dermatofibroma, sclerosing perineuroma, and keloidal fibroxanthoma.

A few anecdotal reports have informed lack of success with d-penicillamine, corticosteroids, methotrexate, and triamcinolone in NS. Our patient denied all treatment options and was further lost to follow-up.

ConclusionNS can be a diagnostic challenge due to its rarity, unknown pathogenesis, and similar differential diagnoses. It must be suspected when a firm nodule resembling a keloid is encountered in patients with no known risk factors for keloid formation or in patients with lcSSc. The association of NS and lcSSc is rare but well-described and must therefore be recognized by rheumatologists. The current knowledge of its pathogenesis and treatment options is limited.

Source of fundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.