To establish recommendations for the management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) to serve as a reference for all health professionals involved in the care of these patients, and focusing on the role of available synthetic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

MethodsConsensual recommendations were agreed on by a panel of 14 experts selected by the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER). The available scientific evidence was collected by updating three systematic reviews (SR) used for the EULAR 2013 recommendations. A new SR was added to answer an additional question. The literature review of the scientific evidence was made by the SER reviewer's group. The level of evidence and the degree of recommendation was classified according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine system. A Delphi panel was used to evaluate the level of agreement between panellists (strength of recommendation).

ResultsThirteen recommendations for the management of adult RA were emitted. The therapeutic objective should be to treat patients in the early phases of the disease with the aim of achieving clinical remission, with methotrexate playing a central role in the therapeutic strategy of RA as the reference synthetic DMARD. Indications for biologic DMARDs were updated and the concept of the optimisation of biologicals was introduced.

ConclusionsWe present the fifth update of the SER recommendations for the management of RA with synthetic and biologic DMARDs.

Establecer recomendaciones para el manejo de pacientes con artritis reumatoide (AR) centrado en el papel de los fármacos antirreumáticos modificadores de enfermedad (FAME) sintéticos y biológicos disponibles, que sirvan de referencia para todos los profesionales implicados en la atención de estos pacientes.

MétodosLas recomendaciones se consensuaron a través de un panel de 14 expertos previamente seleccionados por la Sociedad Española de Reumatología (SER). Se recogió la evidencia disponible mediante la actualización de las 3 revisiones sistemáticas (RS) que se utilizaron para las recomendaciones EULAR 2013, a las que se añadió una nueva RS para dar respuesta a una pregunta adicional. Todas fueron realizadas por miembros del grupo de revisores de la SER. La clasificación del nivel de la evidencia y del grado de la recomendación se realizó utilizando el sistema del Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine de Oxford. Se utilizó la metodología Delphi para evaluar el grado de acuerdo entre los panelistas para cada recomendación.

ResultadosSe emiten un total de 13 recomendaciones sobre el manejo terapéutico de pacientes con AR del adulto. El objetivo terapéutico debe ser tratar al paciente en fases precoces de la enfermedad, con el objetivo de la remisión clínica, teniendo un papel central el metotrexato como FAME sintético de referencia. Se actualizan las indicaciones de los FAME biológicos disponibles, se enfatiza la importancia de los factores pronósticos y se incide en el concepto de optimización de biológicos.

ConclusionesSe presenta la quinta actualización de las recomendaciones SER para el manejo de la AR con FAME sintéticos y biológicos.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most prevalent form of chronic polyarthritis and has the greatest socio-sanitary impact in society today. RA can cause different degrees of disability, loss of quality of life and even increased rates of mortality. In recent years, important advances have been made in the management and treatment of this disease that have resulted in better patient prognosis, although we are still far from a definitive cure.1

In 2010, we witnessed publication of the fourth and latest update of the consensus document by the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER – Sociedad Española de Reumatología) regarding the use of biological therapies in RA.2 In recent years, a vast amount of scientific evidence has been generated about the effectiveness of diverse therapeutic strategies. Meanwhile, new concepts have been developed, such as the optimisation of biological therapies, and new disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) have surpassed their original clinical targets with new indications. This is the reasoning behind this fifth update, which incorporates discussion of these advances and latest insights into a new consensus document.

The present document not only compiles the main aspects of control and treatment with biologic drugs, but it also deals with important aspects in the management of RA, such as early diagnosis, therapeutic objectives, use of chemical drugs (synthetic DMARDs) and comorbidities. The recommendations, however, mainly focus on therapeutic strategies with synthetic and biologic DMARDs.

Similar to previous versions, this document is aimed at healthcare professionals treating patients with RA, especially rheumatologists, as they are usually involved in the management of this disease. These recommendations are not intended to embody a strict protocol for management and treatment of the disease. Instead, they have been created as a foundation to increase the quality of RA patient care and to aid the therapeutic decision-making process.

MethodologyDevelopment of this document began with the empanelling of experts, drawn from an open call to all members of SER. The Committee for Clinical Practice Guidelines and Consensus of SER assessed the candidates’ curricula vitae by evaluating contributions made towards the better understanding of RA. Their objective criteria mainly focused on candidates participation in articles published in high-impact journals during the last 5 years. In the end, the panel of experts was comprised of 14 rheumatologists who are members of SER.

At the first meeting, three different strategies were considered: (a) update the systematic reviews (SR) on which the recommendations of the previous SER Consensus was based2; (b) adapt the recommendations made by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 20133 for the management of RA with synthetic and biologic DMARDs by updating the 3 EULAR SR4–6 that were the basis for said recommendations; and (c) restructure the recommendations in order to include new clinical questions. After a vote, the expert panel opted to update the EULAR 2013 SR and adapt its recommendations to our environment.4–6 However, some aspects of the EULAR 2013 SR, such as those referring to the effectiveness and safety of biosimilars and kinase inhibitors, were excluded from the present update by SER.

An additional SR was created to respond to a new clinical question posed by the panel of experts: “In adult patients with AR and osteoporosis, how safe is the combined treatment of denosumab and biologic DMARD?” Reports of the 4 SRs written by members of the Evidence-Based Rheumatology group, as well as all related methodological materials (development protocol and search strategies), are available for consultation on request (proyectos@ser.es).

The levels of evidence and grades of recommendation were classified according to the system developed by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009).7

At a second meeting, the panellists presented written proposals for each of the recommendations in order to establish a group consensus on the final draft proposal. The degree of agreement for each of the recommendations was established by means of a 3-round Delphi method.

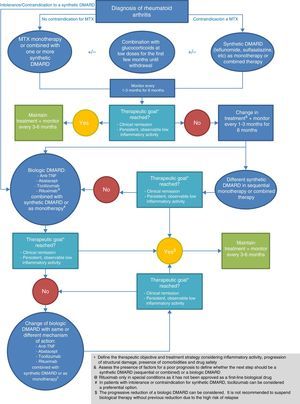

This document presents the 13 recommendations (Table 1) made by the panel of experts, accompanied by their corresponding levels of evidence (LE), grades of recommendation (GR), degrees of agreement (DA) and percentages of panellists who agreed with the recommendation. Recommendations 3, 5, 6, 11 and 12 have been subdivided into several sections. In accordance with the recommendations, a treatment algorithm has been created (Fig. 1) to summarise the treatment approach after a diagnosis of RA. This document also includes a table that summarises the risk management of each of the biological therapies that are currently available in our setting (Table 2).

SER 2014 Consensus Recommendations.

| Recommendation | LE | GR | DA | % votes in favour (DA ≥4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||||

| 1 | It is recommended to begin treatment with a synthetic DMARD as soon as the diagnosis for RA is made. | 1a | A | 5.00 | 0.00 | 100% |

| 2 | The recommended therapeutic goal is to reach a state of clinical remission or, if not, a persistently low degree of inflammatory activity, as evaluated by objective, validated indices. | 1a | A | 4.92 | 0.28 | 100% |

| 3a | Disease activity in patients with RA should be frequently monitored. | 1b | A | 4.69 | 0.85 | 92.31% |

| 3b | Said frequency should be every 1–3 months if the disease is active, a new treatment has been initiated, or the therapeutic goal has not been reached. | 5 | D | 4.77 | 0.60 | 92.31% |

| 3c | Said frequency will be every 3–6 months once the therapeutic goal has been reached. | 5 | D | 4.46 | 0.88 | 92.31% |

| 3d | DMARD treatment should be adjusted 3 months after the start of the latest treatment regimen if there is no improvement and after 6 months if the therapeutic goal has not been reached. | 5 | D | 4.46 | 0.78 | 84.61% |

| 4 | The inclusion of MTX is recommended in the initial therapeutic strategy of patients with RA. | 1a | A | 4.92 | 0.28 | 100% |

| 5a | In patients with a contraindication for MTX, it is recommended to initiate treatment with another synthetic DMARD; in Spain, leflunomide is the most commonly used. | 1a | A | 4.69 | 0.63 | 92.31% |

| 5b | Sulfasalazine is also an effective therapeutic alternative. | 1a | A | 4.46 | 0.66 | 92.31% |

| 6a | The use of a synthetic DMARD, either combined or as monotherapy, is recommended in patients with RA who have not previously received it. | 1a | A | 4.85 | 0.55 | 92.31% |

| 6b | This recommendation is made independently of the concomitant use of glucocorticoids. | 1a | A | 4.62 | 0.77 | 84.61% |

| 7 | The use of low doses of glucocorticoids is recommended in the initial treatment of RA (combined with one or more synthetic DMARDs) during the first months, with progressive reductions until definitive withdrawal is achieved. | 1a | A | 4.31 | 1.11 | 84.61% |

| 8 | When the therapeutic goal is not reached with an initial strategy involving a synthetic DMARD, another synthetic DMARD can be used in sequential or combined therapy, or a biologic DMARD can be added depending on the characteristics of the patient and the presence of factors for a poor prognosis. | 5 | D | 4.85 | 0.38 | 100% |

| 9 | In patients with active RA in whom there is an indication to initiate therapy with a biological DMARD, anti-TNF, abatacept, tocilizumab or, under certain circumstances, rituximab can be used in combination with MTX/other synthetic DMARD. | 1b | A | 4.69 | 0.48 | 100% |

| 10 | In patients with intolerance or a contraindication for a synthetic DMARD, biological treatment can be used in monotherapy. In this case, tocilizumab can be considered as the preferred option. | 1b | B | 4.15 | 0.99 | 76.92% |

| 11a | After a failure to respond to an initial biologic DMARD, it is recommended that the patient be treated with another biologic DMARD. | 1b | A | 4.69 | 0.63 | 92.31% |

| 11b | If the first agent used was an anti-TNF, the patient can receive another anti-TNF or another biological DMARD with a different mechanism of action. | 1b | A | 4.62 | 0.65 | 92.31% |

| 12a | In patients with established RA in remission or persistently low activity, the biological dose can be progressively reduced, especially when used in combination with a synthetic DMARD. | 2b | B | 4.38 | 0.77 | 84.61% |

| 12b | It is not recommended to suspend the biological treatment without previous reduction due to the high risk of relapse. | 2b | B | 4.62 | 0.87 | 92.31% |

| 13 | When defining the therapeutic goal and treatment strategy, including dose adjustments, in addition to the parameters for disease activity and structural damage progression, the presence of comorbidities and drug safety should be considered. | 2b | C | 4.77 | 0.44 | 100% |

RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SD: standard deviation; DMARD: disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs; DA: degree of agreement (1: absolute disagreement, 2: moderate disagreement, 3: neither agreement nor disagreement, 4: moderate agreement, 5: absolute agreement); GR: grade of recommendation; MTX: methotrexate; LE: level of evidence.

Biological Therapy Risk Management.

| Considerations common to all BT | Specific considerations by biological drug | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-TNF | Anakinra | Abatacept | Rituximab | Tocilizumab | ||

| Prior to treatment | (a) Clinical aspects:- Rule out: active infection (including TB, cancer, CHF, cytopenia, demyelinating disease, relevant comorbidity- Rule out recent contacts with TB(b) Complementary studies:- Blood work, biochemistry- Serology HBV, HCV- Chest Rx- Mantoux and Booster; quantiFERON(c) Other measures:- Preventive measures:• Pneumonia and flu vaccines• Assess HBV, meningitis and Haemophilus vaccines according to baseline disease or comorbidities• Assess antiviral treatment if positive HBV; assessment by specialist in hepatology• Avoid vaccines with attenuated or live germs- Instructions for patient:• Symptoms for concern• Hygienic-dietary measures• Planning for pregnancy(d) Special clinical situations:- Pregnancy and breastfeeding: Advise against pregnancy and breastfeeding- Major elective surgery- Immigrant population: evaluation of infections uncommon to our setting | - Consider administration in patients with a history of CHF, ILD, demyelinating disease and HBV/C+Pregnancy:• FDA category: B• Transference through the placenta or breast milk is very low with certolizumab pegol• Interrupt 3–24 weeks before, depending on the biological agent (see drug data sheet) | Pregnancy:• FDA category: B• Interrupt 10–12 weeks before | Pregnancy:• FDA category: C• Interrupt 14 weeks before | - Consider its administration in patients with a history of CHF or other serious cardiac diseases, and ILD- Consider antiviral treatment if HBV+Before each perfusion, premedication should be given with glucocorticoids, analgesia/antipyretic and an antihistamine.Determine immunoglobulin levelsPregnancy:FDA category: CInterrupt one year before | - Consider its administration in patients with a history of demyelinating disease- Evaluate neutrophils, platelets and hepatic enzymesPregnancy:FDA category: CInterrupt 12 weeks before |

| During treatment | (a) Clinical aspects:- Appearance of infections (including TB), severe cytopenia, demyelinating disease or optical neuritis, cancer- Appearance or worsening of CHF and lung disease(b) Complementary studies:- Monthly general blood work and biochemistry for the first 3 months, later every 3–6 months.(c) Other measures:- According to patient progress | Appearance of worsened CHFSkin neoplasmsWatch for appearance of neoplasms in COPD patients or with a smoking history | Appearance of COPD or declining lung function in patients with previous COPD | Reactions during perfusionPotential risk for infections, including PMLWatch for development of late neutropenia | ||

| Suspension of treatment | - Appearance of cancer, demyelinating disease or optical neuritis, severe cytopenia, new interstitial lung disease or decline in previous disease, or other severe events related with the drug- Temporary suspension if infection or major elective surgery in perioperative periodAssess pregnancy or breastfeeding | |||||

ILD: interstitial lung disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHF: congestive heart failure; PML: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy; BT: biologic therapy; TNF: tumour necrosis factor; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus.

The EULAR 2013 systematic review on the efficacy of synthetic DMARD4 and the related update by SER for this consensus document both demonstrate that treatment with synthetic DMARDs improves the symptoms and signs of RA (LE 1a). Thus, it is logical that the panellists are in complete agreement for this recommendation. Additionally, the panel emphasised the importance of the diagnosis and early treatment of the disease because a recently published SR supports the concept of a “window of opportunity”. Said review has found a significant correlation between disease duration before the start of treatment with DMARD and radiological progression (LE 1a). Moreover, the same study reported that the duration of symptoms before the start of treatment with DMARD has a significant negative influence on the possibility of later maintaining remission in the absence of treatment with DMARD (LE 1a).8

This first recommendation differs from those of EULAR,3 which established the option of initiating treatment with both synthetic and biologic DMARDs. One reason for starting treatment with a synthetic DMARD stems from the fact that subanalysis of the TEAR study in patients with RA and factors for a poor prognosis showed no relevant mid-term differences when treatment was initiated with methotrexate (MTX) monotherapy versus combined therapy either with or without a biologic agent.9 This study revealed the possibility of changing to a combined therapy regimen (with another synthetic DMARD or a biologic drug) 6 months after the start of treatment, which is feasible in our standard clinical practice. Two years after follow-up, 30% of patients continued treatment with MTX monotherapy, and no relevant differences were observed with those groups that received combined therapy.9

Given that early therapy with DMARDs has a relevant effect on later disease progression, and despite the fact that diagnosis of RA is based on the personal impression of the rheumatologist treating the patient, the 2010 classification criteria can help re-adjust the way in which patients with initial onset arthritis are treated by providing greater sensitivity for the diagnosis of RA.10 Considering that the risk-benefit correlation of early therapy with a synthetic DMARD, especially MTX, is favourable and its management is well known,6 the prescribing of synthetic DMARDs could be extended to patients with undifferentiated arthritis if the rheumatologist suspects that it could progress to RA. Different therapeutic strategies have been tried in these patients in an attempt to halt the progression towards RA and to improve the possibility of achieving treatment-free remission.11–13

Recommendation 2. The Recommended Therapeutic Goal Is to Reach Either a State of Clinical Remission or, Alternatively, a Low Degree of Persistent Inflammatory Activity, as Evaluated by Objective, Validated IndicesThis recommendation is based on the fact that it is now possible to achieve clinical remission in a significant percentage of patients. Although there is no unequivocal definition for the concept of “remission”, the current conviction is that clinical remission in RA is an attainable therapeutic goal.

Several observational studies show that 20%–35% of patients with early RA reach clinical remission.14 Furthermore, approximately half or more of patients with early RA who are treated with intensive therapy (i.e., with a combination of biological and synthetic DMARD, begun either at detection or very early on)15,16 or with a strategy of close therapeutic control of the disease,17,18 achieve short-term remission. Nonetheless, long-lasting clinical remission is much less frequent.19,20 The presence of long-term remission is associated with less advanced structural damage and lower disability rates.21,22 It has also been well established that the outcomes are worse if the patient has persistent inflammatory activity, even if low grade.23

The previous SER consensus proposed a low degree of activity as a therapeutic goal, defined quantitatively by the cut-off points of validated activity indices.2 The latest EULAR 2013 recommendations3 insist that remission is an attainable objective in a significant percentage of patients and advocate the use of stricter definitions, such as the ACR/EULAR criteria,24 which correlate better with a state of practical absence of synovitis. The reason is that the definition of remission based on the Disease Activity Index (DAS28), which is widely used in our clinical practice, has important limitations; for example, patients with several inflamed joints and radiological progression can be considered in remission based on this scale.25 The ACR/EULAR remission criteria, initially designed for use in clinical trials24 and validated under daily clinical practice conditions,26 are stricter; only 7%–20% of patients in observational studies meet these criteria.27–29 In addition, one must also consider that factors unrelated to RA, such as subjective patient characteristics30 or the presence of comorbidities,29 can mean that some patients do not meet remission criteria. Thus, a significant percentage of patients either do not reach clinical remission or their remission is not long-lasting. In these cases, especially in patients with established RA, a low degree of inflammatory activity can also be considered a reasonable therapeutic goal (defined by validated indices)3,24 since better outcomes have also been described in the presence of low inflammatory activity compared to intermediate or high inflammatory activity.31

As for the need to include criteria from imaging studies when defining remission, it is well known that a significant percentage of patients in apparent clinical remission have subclinical synovitis that is detectable with MRI or ultrasound.32 Approximately half of such patients have active synovitis with a positive Doppler signal on ultrasound.33,34 The presence of subclinical synovitis is a predictive factor for the loss of remission during follow-up34,35 and could explain the radiological progression observed in patients in an apparent state of clinical remission.33,34 Furthermore, the use of stricter remission criteria using the ACR/EULAR or SDAI criteria is associated with lower rates of subclinical sinovitis36,37 than when DAS28 is used. Nonetheless, the panel holds that there is still no solid evidence to establish a definition of remission that includes an “imaging studies” dimension. However, the panel recognises the importance of imaging techniques for assessing the presence of synovitis in cases of difficult or uncertain physical exploration, which can provide additional information for the management of some patients.

Moreover, as in the previous SER consensus document,2 the therapeutic goal has not been reached if there is persistent inflammation that remains unresolved following local therapeutic measures in important joints or when significant radiological progression is detected.

Recommendation 3. Frequent Monitoring of Disease Activity in Patients With RA Is Recommended. This Frequency Should Be:- •

Every 1–3 months if the disease is active, a new treatment has been initiated, or the therapeutic goal has not been reached.

- •

Every 3–6 months once the therapeutic goal has been reached.

Treatment with DMARDs should be adjusted 3 months after the start of a new dosage if there is no improvement, and 6 months thereafter if the therapeutic objective has not been reached.

The “treat to target” strategy has demonstrated clear benefits in efficacy with regards to overall disease evolution over the mid- and long-term, regardless of the pharmacological treatment applied. In the context of this strategy, this recommendation attempts to establish follow-up schedules and times for changes in therapy.

There are no specific data regarding the appropriate periodicity required for monitoring patients with RA. The studies included in both the EULAR 2013 systematic review on the efficacy of DMARDs,4,5 as well as the updates of said revisions done by SER for this consensus, were designed to assess treatment effectiveness, not to define monitoring strategies. Even so, several studies designed to assess therapeutic strategies propose monitoring periods ranging from 4 weeks to 4 months16,38–49 (LE 1b-2b). Only one study assessed disease activity every 24 weeks.50 The period that is considered appropriate before making treatment changes in these studies ranges from 4 to 26 weeks.

In this context, the study by Aletaha et al.51 demonstrates a correlation between disease activity after 3 months and after one year of treatment Therefore, the response reached after 3 months of treatment is highly predictive of the clinical progression during the first year.

In general, the results of the studies mentioned above are applicable to the Spanish healthcare system. Nonetheless, given the organisational differences at various hospitals, the creation of monographic treatment units or, at least, the structure needed, would provide for preferential and frequent care during periods of treatment adjustment or inflammatory activity. In addition, given the variability of resources in our health care system, the panel believes that the collaboration of other medical professionals, such as the nursing staff, would be necessary for successful compliance with this recommendation.

Recommendation 4. It Is Recommended to Include MTX in the Initial Therapeutic Strategy of Patients With RAThis recommendation, included in those of EULAR 2013,3 has been adopted unchanged by the panel of experts responsible for this consensus. Said recommendation sanctions the inclusion of MTX in the therapeutic strategy, without making allusions to administration as monotherapy, therapy in combination with other synthetic DMARDs, or even exceptional cases in which therapy combined with another biologic agent could be initiated.

MTX is not merely very effective for the treatment of RA, but in fact is regarded as the drug of choice. In the most important studies involving MTX as a monotherapy in patients who had not previously received it, 25%–50% reached ACR70, which in many cases meant remission or low activity.52–54 No less relevant is its impact on structural damage. The first study that compared MTX monotherapy with a biological agent (etanercept) in monotherapy or combined with MTX demonstrated that, over the course of 2 years, 60% of patients who received MTX monotherapy did not progress radiologically; in 85%, the change in the Sharp score was less than or equal to the minimal detectable change (5.72 units).55 MTX should be used in rapid escalation such that, in a period of 8–16 weeks, the optimal dose is reached; i.e., at least 15mg (the maximum is generally 25mg).56 Administration is always weekly and preferably in one oral or parenteral dose. Although it is difficult to determine how rapidly dosage is escalated in our country, one must be aware of the fact that, in most cases, the minimum effective dose is approximately 15mg weekly and can be increased to 25–30mg per week. The emAR II study reported that the average maximum dose of MTX in 2008–2009 for patients with RA was 15mg/week (interquartile range from 10 to 20mg/week). Thus, a significant number of patients were probably not receiving the optimal drug dosage.57

Treatment with MTX involves the administration of folic or folinic acid 24h after receiving a dose of MTX; the former does not affect the efficacy of MTX and reduces the toxicity of this drug.58,59 When this occurs, it is not severe and does not require suspension of treatment; rather, a common practice is to increase folate supplementation.58,59 Patients who do not tolerate weekly 15mg doses are usually given smaller weekly doses ranging between 7.5 and 12.5mg.

Generally speaking, MTX is taken orally. However, when a patient receives weekly doses of 20mg or greater, parenteral MTX administration is preferable, since the oral bioavailability of this drug diminishes as the dosage increases. Moreover, the parenteral bioavailability increases in a linear manner.60 There is ample evidence that patients who respond insufficiently to oral doses have a better response to the parenteral route.61–64 Digestive tolerability, as well as that of other organs, seems to be better with parenteral administration.61–64

The efficacy data for MTX remain indisputable, both in monotherapy and when administered in combination with either synthetic or biologic DMARDs. In fact, only 2 agents, tocilizumab and tofacitinib, have been shown to be superior in monotherapy when compared with MTX.65,66

In general, MTX is well tolerated by most patients. Nonetheless, there are certain patients with severe hematologic, hepatic or pulmonary involvement in whom MTX would be contraindicated from the outset. In these cases, it is necessary to start the treatment with other drugs that have also proven effective. See recommendation 5.

Recommendation 5. In Patients With Contraindications to MTX, It Is Advisable to Initiate Treatment With Other Synthetic DMARDs. In Spain, the Most Frequently Used DMARD Is Leflunomide, Although Sulfasalazine Is Also an Effective Therapeutic AlternativeLeflunomide is an effective drug in RA from both a clinical standpoint and in terms of radiological progression. No differences have been found in comparative studies with MTX, whether the doses of MTX used in these studies were optimal for this drug remains debatable.67,68 Leflunomide is also effective when combined with biological agents,69,70 although the available evidence compared to MTX is scant. Indeed, the main clinical assays involving biological agents have used MTX.

The results from studies done with leflunomide are consistent; therefore, this drug can be considered the first alternative to MTX when use of the latter is not possible. In Spain, leflunomide (at a dose of 20mg per day in monotherapy) has become the most widely used drug in patients with intolerance or contraindications to MTX.57

Sulfasalazine with enteric coating at a dose of 3–4g per day has demonstrated effectiveness similar to MTX from both a clinical and radiological standpoint.71–75 Sulfasalazine has the advantage of being safe during pregnancy, which offers an added advantage over the use of MTX or leflunomide. One disadvantage to using such doses is the number of tablets that the patient must take each day (between 6 and 8), which could affect treatment compliance. Nonetheless, a randomised clinical trial (RCT) was designed with 3 therapeutic approaches in patients with RA who received: (a) leflunomide at 20mg per day after a load of 100mg the first 3 days; (b) placebo; and (c) sulfasalazine up to a maximum of 2g/per day for 24 weeks. The results demonstrated that both drugs boasted superior efficacy versus placebo, with no differences between the two.76 The decision to administer 2g of sulfasalazine as a monotherapy was based on previous studies in which this dose had been shown to be effective both at the initiation of treatment as well as during maintenance,74,75,77–79 although occasionally the dose of 2g was administered in combined therapy.

Therefore, in those patients in whom MTX is contraindicated, sulfasalazine could be taken at a dose of 2g in monotherapy if the patient does not tolerate higher doses. However, what is most common is to prescribe these doses in combination therapy with MTX and hydroxychloroquine.80–82 In Spain, sulfasalazine with enteric coating is not available, which explains the poor tolerability of 3–4g doses in a large number of patients. Thus, the use of this drug in RA is very limited in our country.57,83

Another widely used drug in the 1970s and 1980s was gold salts. This drug was considered an alternative to MTX in the first EULAR recommendations.84 However, gold salts disappeared from the list of recommended drugs in the EULAR 2013 recommendations.3 The main reason why gold salts are not used anymore is due to the advent of MTX and from the severe side effects (hematologic and renal toxicity) caused by gold salts in some patients. As a result, in many countries (including Spain), the drug is not widely available.

Last of all, chloroquine and, fundamentally hydroxychloroquine, are drugs that are usually found to be safe, effective agents in cases of very mild RA with little inflammation.85,86 Nonetheless, their use as a monotherapy in RA is practically non-existent and has been almost wholly limited to combined therapy, where they have been widely used with sulfasalazine and MTX.80–82 Like sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine is safe for use during pregnancy,87 which offers some advantages in certain clinical situations. Other drugs, such as azathioprine, cyclosporine and cyclophosphamide, are not discussed in this section because their initial use in RA is practically non-existent.

Recommendation 6. The Use of Synthetic DMARDs Is Recommended in Patients With RA Who Have not Previously Taken Them, Either as Monotherapy or in Combined Therapy. This Recommendation Is Made Independently of the Concomitant Use of GlucocorticoidsThis recommendation once again underlines the fact that the first treatment strategy in a patient with early stage RA should include synthetic DMARD(s). Given the current controversy over the use of DMARDs in monotherapy or combined therapy, this recommendation was initially much debated, although it ultimately met with a high level of agreement.

The EULAR 2013 SR regarding the efficacy of synthetic DMARDs4 confirmed the effectiveness of these drugs in RA based on several RCTs verifying this fact (LE 1a). Specifically, the efficacy of MTX was demonstrated in both first- and second-line DMARD use (LE 1a). Likewise, the EULAR 2013 recommendations3 identified 5 studies43,88–91 suggesting that combined therapy with synthetic DMARDs was superior to monotherapy with MTX (LE 1a). Among these 5 studies, one even proposed that the efficacy of combined therapy with a synthetic DMARD could be equal to that of biological therapies in combination with MTX. Nonetheless, the EULAR 2013 SR also argued that said studies suffered methodological limitations that hindered their interpretation. It also noted that other studies had demonstrated that sequential monotherapy (by changing a DMARD if there is no response) was as effective as combined therapy in terms of clinical, functional and structural results.92 In spite of the latter, the EULAR 2013 recommendations concluded that combined therapy with or without steroids was an adequate strategy in patients with RA. This combined therapy should generally include MTX, since other combinations that do not include it have not been sufficiently studied.

The previously mentioned SR4 specifically addressed 2 of the 5 studies mentioned above. The tREACH study (LE 1b) is an RCT with three treatment modalities in which patients with recent-onset RA were randomised to receive: (a) a combination of MTX, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine with intramuscular glucocorticoids; (b) the same combination, but with oral glucocorticoids at a decreasing dosage; and (c) only MTX together with the same descending dosage of oral glucocorticoids. The study found that, after 3 months of follow-up, there were no differences in DAS28, ESR and swollen joints among the three treatment groups. However, there were differences in HAQ, painful joints and CRP which were superior in the monotherapy group compared to the combined therapy groups.88 In contrast, the TEAR study (LE 1b) found no differences in clinical results or in radiological damage between the combined therapy used from the start versus sequential therapy.89

The update of this SR has also identified 2 new studies on this subject. The first (LE 1b), a non-inferiority study, compared a COBRA-light prescription (prednisolone in decreasing dosage + MTX) with the original COBRA prescription (decreasing doses of prednisolone+MTX+sulfasalazine). After 6 months, the authors found that both interventions reduced disease activity in early RA and no differences were seen between the two.93 The second study (LE 1b), a post hoc study of the aforementioned TEAR study, analysed the MTX group versus the combined therapy groups (etanercept+MTX, and MTX+sulfasalazine+hydroxychloroquine) and found that patients who received MTX monotherapy (after 102 weeks) maintained benefits similar to groups that received combined treatments.9

As for safety, the different studies analysed revealed that synthetic DMARDs are safe, both in monotherapy and in combined therapy. Only 2 studies (LE 2a) suggest an increase in the rates of cancer94 and infectious lung disease95 when MTX (versus another synthetic DMARD) was involved.

The results of the identified studies can be directly applied to our healthcare system since the therapeutic agents evaluated are commonly used in our setting. Both strategies, monotherapy and combined therapy, are effective in patients with RA, with or without steroids. Preferences, expectations and side effects should be considered when discussing treatment options with patients.

Recommendation 7. Low Doses of Glucocorticoids Are Recommended in the Initial Treatment of RA (in Combination With One or More Synthetic DMARDs) During the First Few Months. Doses Should Be Progressively Reduced Until Their Use Can Be Completely WithdrawnThere is evidence about the usefulness of low doses of glucocorticoids in the initial treatment of RA. What has not been defined, however, is the optimal duration of treatment since only 2-year studies have been published. Based on expert opinions, the EULAR 2013 SR suggests not prolonging administration for more than 6 months.

The EULAR 2010 SR on the management of RA with glucocorticoids96 identified 11 RCT (including 3 Cochrane SR). It concluded that the addition of low glucocorticoid doses (7.5mg/day or less) to the initial synthetic DMARD treatment of recent-onset RA is clinically effective and reduces radiological progression when used continuously for 2 years (LE 1b).97–99 The use of glucocorticoids in RA patients with more than 2 years of disease progression only led to improvements in terms of signs, symptoms and functional state.100 The use of glucocorticoids thus offers a bridge therapy until the effect of a new DMARD provides better clinical results after one month of treatment (LE 1b). However, its long-term clinical and radiological usefulness still has not been determined.101,102

The EULAR 2013 SR4 identified 2 new RCT (SAVE and CAMERA-II [LE 1b]) that evaluated the efficacy of glucocorticoids in recent-onset RA combined with synthetic DMARDs. The CAMERA-II study demonstrated that 10mg per day of prednisone in a control strategy that was closely associated with MTX (up to 30mg/week) reduced radiological damage after 2 years of treatment, and increased the probability of a clinical response (e.g., higher remission rates, lower levels of DAS and better results in HAQ). This treatment strategy also yielded clinical improvement in less time and had less need for other future treatments (e.g., other synthetics or biologic DMARDs).103

The SAVE study demonstrated that administration of a single dose of 120mg of prednisolone to patients with very early stage undifferentiated arthritis was not able to prevent the later progression of RA. Nor did it induce clinical remission or the need to initiate a synthetic DMARD.104 The tREACH trial (LE 1b), mentioned previously, compared clinical effectiveness in patients with early-phase RA (<1 year of symptoms) for one year in 3 treatment modalities: (a) initial triple therapy with a single intramuscular dose of glucocorticoids (120mg 6-methylprednisolone or 80mg triamcinolone); (b) initial triple therapy with oral glucocorticoids withdrawn over 10 weeks; and (c) MTX as a monotherapy with glucocorticoids as in (b). The authors used a “treat to target” strategy for the dose adjustments and intensification to biological therapy. After 3 months, better clinical results were observed (40% less intensifications), but there were no differences in the radiological progression after one year. No clinical or radiological differences were found between the 2 bridge therapies involving glucocorticoids.105

The results of the different studies identified in the 2 EULAR SR are consistent and demonstrate the effectiveness of adding glucocorticoids to the initial treatment (up to 24 months) in patients with recent-onset RA. Some studies also showed that monotherapy with glucocorticoids (e.g., with no associated synthetics or biologic DMARDs) was effective in controlling the symptoms and signs of RA.106,107 Despite the fact that some controlled clinical trials suggest that the side effects associated with the use of low doses of prednisone are modest,108 there is still not sufficient evidence about its long-term safety and efficacy in order to recommend its prolonged use, except in unique situations.

Recommendation 8. When the Therapeutic Goal Has not Been Reached With the Initial Synthetic DMARD Strategy, Either Another Synthetic DMARDs Can Be Used in Sequential or Combined Therapy, or a Biologic Agent Can Be Added, Depending on Patient Characteristics and the Presence of Poor Prognostic FactorsThe panel of experts determined that risk stratification is an important aspect in the management of RA. Factors indicating a poor prognosis include a state of high disease activity, positivity for rheumatoid factor and/or anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) and the presence of radiographic erosions.109,110

In patients who do not present factors for a poor prognosis and who have failed to respond to an initial strategy with a synthetic DMARD (which almost always includes MTX) the panel recommends using another strategy with a synthetic DMARD as monotherapy (leflunomide or sulfasalazine) or in combination (MTX+hydroxychloroquine+sulfasalazine, or MTX+leflunomide). In patients with some type of factor indicative of a poor prognosis, the recommendations are as follows: add a biologic DMARD or, if the first strategy involved an initial synthetic DMARD in monotherapy, then a combination of a synthetic DMARD could be used (MTX+hydroxychloroquine+sulfasalazine or MTX+leflunomide).

In RA patients who do not adequately respond to MTX, the addition of hydroxychloroquine+sulfasalazine has demonstrated a clinical effectiveness equivalent to the addition of an anti-TNF agent in 3 RCT (IFX in the SWEFOT study,91 etanercept in the TEAR9,89 and RACAT90 study) all of which were of high quality (LE 1b), although the radiological evolution in one of the clinical trials was significantly less in the patient group that received an additional anti-TNF agent.91

There are no data from clinical assays on the use of MTX+leflunomide compared with the addition of a biological agent in patients with RA and insufficient response to MTX. Therefore, based on existing scientific evidence, this panel cannot recommend its use in RA patients with factors for a poor prognosis and insufficient response to monotherapy with MTX. Nonetheless, the panel is conscious of the poor tolerability of Spanish patients to sulfasalazine, as well as the widespread acceptance in our healthcare system regarding the effectiveness and safety of combining MTX and leflunomide. In selected cases, the combination of MTX and leflunomide could be a reasonable alternative to the use of MTX+hydroxychloroquine+sulfasalazine.

In addition, after an insufficient response to MTX in RA patients with no factors for a poor prognosis, the use of a biologic DMARD could be considered in those cases in which (1) the patient characteristics suggest the likelihood of side effects with other synthetic DMARDs (monotherapy or combined) or (2) when there is deficient compliance with the therapeutic prescription.

The panel emphasises that, following a poor response to the initial strategy using a synthetic DMARD, it is of the utmost importance to closely follow the patient. The basic objective is to at least reach a state of low disease activity and, ideally, to enter remission within 6 months of having initiated therapy with DMARD.

Given the importance of the efficient use of healthcare resources, the panel believes that higher mid- and long-term cost-effectiveness is best achieved by inducing a state of disease remission during the first 6 months of treatment. Therefore, the use of a biologic DMARD is justified when the first strategy (synthetic DMARD) has failed in those patients with factors for a poor prognosis.

Recommendation 9. In Patients With Active RA in Whom There Is an Indication to Initiate Therapy With a Biologic DMARD, It Can Be Used in Combination With MTX/Another Synthetic DMARD, Anti-TNF Drugs, Abatacept, Tocilizumab or, in Certain Circumstances, RituximabBased on new indications and evidence for certain biological drugs, the number of available therapeutic agents has increased.

In patients with RA and insufficient response to MTX, the 9 biological agents available in Spain (abatacept, adalimumab, anakinra, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab and tocilizumab) show promising evidence (LE 1a) not only of the rescue effect, but also of the greater therapeutic effectiveness of the combine use of a biologic DMARD+MTX versus continued MTX monotherapy.111–116 In this scenario, combined biologic DMARD+MTX vs MTX presents a relative risk (RR) of reaching an ACR70 response of 4.07 (95% CI: 3.21–5.17). In this context, there are also data that confirm demonstrating the higher efficacy of combining a biologic DMARD+synthetic DMARD (other than MTX) vs a synthetic DMARD in those patients with an insufficient response to a synthetic DMARD (RR to obtain an ACR70 response: 4.74 [95% CI: 2.63–8.56]).5

Combining a biologic agent with another is not recommended since such a regimen does not provide greater effectiveness in controlling RA and the risk of adverse events, especially infections, increases. Currently there remains a lack of quality scientific data analysing the safety of using denosumab with other biological therapies in patients with RA.

All biologic DMARDs (except anakinra) show a similar therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of those RA patients who respond poorly to MTX (LE 1a).5 Two clinical assays (LE 1b) have directly compared the therapeutic effect of 2 biological agents: the AMPLE study,116 which compared abatacept+MTX versus adalimumab+MTX in cases of RA with less than 2 years of mean disease duration; and the ADACTA study,117 which compared tocilizumab on monotherapy versus adalimumab on monotherapy. In the former, the clinical and radiological responses were similar, while in the latter tocilizumab was more effective than adalimumab.

In active RA patients with an insufficient response to MTX, biological treatment is usually initiated with anti-TNF combined with MTX. This is done for several reasons, including the greater likelihood that the physician has experience with these agents, as well as the greater availability of long-term safety data. Clinical trials and meta-analyses52,118 (LE 1a) have demonstrated that anti-TNF combined with MTX is superior to these biological agents in monotherapy, especially with regards to the slower radiological progression of joint damage (although there is still some doubt about the actual magnitude of this effect).

In RA patients who respond poorly to MTX, the choice of abatacept, rituximab or tocilizumab depends on different factors: patient preference, drug cost, comorbidities, administration pathway, physician experience and indications (rituximab has not been approved when there is failed response to MTX). These biological agents seem very similar to each other, with the following considerations (LE 1b)119–122:

- •

The response to rituximab is greater in patients with rheumatoid factor and/or ACPA+.

- •

The immunosuppression/immunomodulation exerted by these 3 biologic DMARDs reverts more rapidly with abatacept and tocilizumab than with rituximab, the effects of which on immune function can be longer lasting.

- •

Certain comorbidity factors (demyelinating disease, congestive heart failure, lymphoma) can contraindicate the use of an anti-TNF and favour administration of a biological agent.

- •

Abatacept may carry less risk of triggering serious infections, which is of particular relevance in elderly patients and those with comorbidities.

This recommendation was the subject of intense discussion among members of the panel of experts, and it was necessary to twice revise it in order to reach agreement consensus of 77% after the third Delphi round. The writing in the present recommendation attempts to explain that while tocilizumab is more likely to be effective in this patient profile, any of the other options approved for RA are also acceptable.

This recommendation is based on 3 lines of evidence. The first stems from the only direct comparative study between 2 biologic DMARDs in monotherapy: ADACTA.117 This was a randomised, double-blind study with a low risk for bias (LE 1b) that demonstrated the superiority of tocilizumab versus anti-TNF adalimumab. This proved true both in monotherapy, when the efficacy was measured by DAS28, and when using other indices with less weight of the acute phase reactants (ACR20, 50, 70, SDAI or CDAI). Moreover, tocilizumab is the only biologic DMARD that has demonstrated its biological superiority over MTX in monotherapy65,123,124 (LE 1b). In fact, none of the other biologic DMARDs have consistently shown an effectiveness superior to MTX in monotherapy, except in terms of its effect on structural damage or its quicker action.5,56,118 Third, monotherapy with tocilizumab has an effectiveness similar to the combined MTX therapy125 (LE 1b), while anti-TNF is less effective in monotherapy than when combined with MTX.5,118,126 Therefore, these 3 lines of evidence support the contention that tocilizumab is more effective than anti-TNF in monotherapy treatment of RA patients.

A possible limitation of this recommendation lies in the fact that there is only direct comparative data for tocilizumab with adalimumab. Nonetheless, considering the existence of data from multiple studies reporting an effectiveness very similar to that of other biologic DMARDs in monotherapy,5,56,118,126 as well as the results mentioned in the previous paragraph, it is reasonable to extrapolate the data on adalimumab to other anti-TNF drugs in this context, although for this reason the grade of recommendation is reduced to B.

One clarification is necessary in the case of etanercept. There was an open 16-week study (ADORE) in which etanercept monotherapy reached an efficacy similar to its combination with MTX.127 However, two other studies, the 52-week double-blind randomised TEMPO study118 (LE 1b) and the 52-week randomised JESMR study126 (LE 1b), showed that the combination of etanercept+MTX was more effective compared to etanercept monotherapy. Furthermore, this greater effectiveness was also noted in a recent Cochrane meta-analysis.128 There are no studies comparing etanercept with other anti-TNF drugs in monotherapy. Therefore, despite certain contradictory evidence surrounding this drug, and in the absence of direct comparative studies with other anti-TNF in monotherapy, the majority of the panel decided that there is no consistent evidence to regard etanercept differently from the use of other anti-TNF drugs in monotherapy.

Lastly, the panel would like to emphasise that the intention of this recommendation is not to support monotherapy with biological agents. Rather, in line with the EULAR recommendations,117 there is agreement that a given biologic DMARD should preferentially be used in combination with a synthetic DMARD, even in the case of tocilizumab.

Recommendation 11. Following a Failed Response to an Initial Biological DMARD, the Panel's Recommendation Is to Treat the Patient With Another Biologic DMARD. If an Anti-TNF Had Been Used, the Patient Can Receive Another Anti-TNF or Another Biologic DMARD That Utilises a Different Mechanism of ActionAt least 5 randomised, double-blind clinical trials129–133 have demonstrated the effectiveness of abatacept, rituximab, tocilizumab and golimumab in an analysis of the primary objective. Moreover, a subanalysis studied the efficacy of certolizumab in patients who had not previously responded to another biologic agent (LE 1b). There are no clinical trials comparing the effectiveness of secondary biological agents. However, a recent meta-analysis134 involving indirect comparisons concluded that in patients who have failed to respond to an anti-TNF, the use of abatacept, rituximab or tocilizumab can be superior to the use of a second anti-TNF (LE 1a). This meta-analysis supports observational studies of registries135–139 that compared the effectiveness of a second anti-TNF with rituximab, abatacept or certolizumab (LE 2b).

All of the published evidence shows the effectiveness of using a second biological agent in patients who failed to respond to an anti-TNF. There is a lack of published data on the effectiveness of a second biological agent in patients who did not respond to biologicals other than anti-TNF.

These results are applicable to our health care system, where anti-TNF is generally used as the first biological agent.

In clinical trials, the safety of the second biological drug did not seem very different from the control group129–133 (LE 1b).

Recommendation 12. In Patients With Established RA in Remission or Low Persistent Activity, the Biological Dose Can Be Progressively Reduced, Especially When Used in Combination With a Synthetic DMARD. Due to the High Risk of Relapse, Suspension of Such a Biologic Treatment Is not Recommended Without Previous ReductionOne area of great interest and uncertainty is whether the dose can be reduced, or the biological treatment interrupted, while still retaining the same degree of efficacy.

Several studies46,140–147 indicate that in cases of established RA, withdrawal of anti-TNF is usually not very effective.

In the PRESERVE study, 12 months after the suspension of anti-TNF therapy, 57% of patients with low activity had a new disease episode, compared with 21% of those who reduced the dose of etanercept (25mg etanercept/week+MTX) and 18% who continued with complete doses (50mg etanercept/week+MTX).143 In the CERTAIN study, only 3 out of 17 patients who had reached remission (CDAI ≤2.8) by week 24 of treatment with certolizumab were able to maintain it by week 52.46 Last of all, in the DOSERA study, only 13% of patients who suspended anti-TNF maintained a state of low activity/remission (DAS28 ≤3.2) versus 44% of patients who received half the dose and 52% that continued at full doses (50mg etanercept/week+MTX).147

In established RA, several observational studies about the withdrawal of anti-TNF found 12-month remission rates between 25 and 43%,140,145 and for low activity rates ranging from 16146 to 18.5141 to 55%.145

In cases of recent-onset RA initially treated with anti-TNF, withdrawal of the biological drug is more effective. After suspension of anti-TNF, the TNF 20 study found 12-month remission rates of 70%148 and in the BeST study the percentage was 52% after 5 years. The remaining 48% of the patients required treatment renewal after 17 months (IQR 3–47).149,150 In the IDEA study, 78.6% of the patients in remission for more than 6 months maintained said state when the anti-TNF was suspended.44 In the PRIZE study, 38.5% of patients in remission who continued with MTX alone remained in remission at week 39, versus 63.5% of the patients treated with half of etanercept+MTX and 23% treated with placebo.151 Last of all, in the HIT-HARD study, there were no differences in the DAS 28 between patients randomised to receive MTX+placebo versus MTX+adalimumab during the first 24 weeks versus those in whom the treatment with adalimumab was interrupted and then continued with MTX+placebo, although significant differences were observed in terms of radiographic progression.152 The OPTIMA study reported that most patients who discontinued treatment with adalimumab after reaching the objective of low activity after 6 months of treatment with adalimumab+MTX exhibited either low activity or remained in remission for the following 52 weeks.16

There are studies with agents other than anti-TNF. In the ORION study, which included patients treated with abatacept in remission (DAS28-CRP <2.3), 41.2% whose treatment was suspended maintained remission at week 52 versus 64.7% of those who continued with treatment.153 In the AVERT study, 14.8% of the patients in remission with abatacept+MTX after 12 months of treatment maintained remission 6 months after the withdrawal of all treatment. In those treated only with abatacept, 12.4% were able to maintain said state 6 months after suspension of the biological drug.154

The DREAM study, which evaluated remission rates after the suspension of tocilizumab, found that after 52 weeks 13.4% of the patients continued with low activity and 9.1% reached remission.155 In the ACT-RAY, 50.4% of the patients in remission at week 52 (those treated with either tocilizumab+MTX or tocilizumab+placebo) remained in remission for 52 weeks after tocilizumab was withdrawn.156

Regarding the effectiveness of biological therapy dose reduction in maintaining the state of remission or low activity, the PRESERVE,143 DOSERA147 and PRIZE151 studies-all of which compared the efficacy of the complete withdrawal of a biological agent+MTX (etanercept in 3 cases) versus dose reduction-found that reduced dosing was less effectiveness compared to a full dosage. These differences, however, were not statistically significant.

Additionally, three observational studies showed that dose reductions within a “treat to target” strategy can be effective in clinical practice.146,157,158

A more realistic approach, although one with much less evidence behind it, is dose reduction once the therapeutic objectives are reached. With this strategy the results are slightly lower than with treatment at full doses. Recently, SER has published a consensus document that makes recommendations based mainly on expert opinions about this subject.159

Recommendation 13. Comorbidities and Drug Safety Should Be Considered When Defining Therapeutic Goals and Treatment Strategies (Including Dose Adjustments, Disease Activity Parameters and Progression of Structural Damage)The purpose of this recommendation is to address the potential existence of comorbidities when treating RA. The presence of comorbidities should be considered in addition to the risks and possible adverse effects of these drugs.

The presence of comorbidities can effect both treatment strategies and efficacy results (LE 2b).160–162 Currently, there are no specific criteria to indicate biological agents for use in patients with significant comorbidities. In such patients, even in those with high disease activity or progressive structural deterioration, the start of a given therapies is often delayed. The assessment of the risk/benefit ratio in these patients would help to select the most appropriate medication and adjust the dose (LE 5). In studies that have examined treatment adjustment strategies, the safety profiles among the different dosages prescribed proved similar.16,143,163

The therapeutic objective should be to reach remission or low disease activity. Nevertheless, due to the aforementioned considerations, attaining either goal in patients with comorbidities should not assume all precedence and, in fact, good results can also be achieved.

In patients with RA, a persistently high degree of inflammation can be associated with the appearance of comorbidities. Therefore, effective RA treatment can also help prevent them (LE 2b).164–168

The results on which this recommendation is based have a low LE given that the presence of comorbidities is usually a cause for exclusion in clinical trials. The conclusions are indirectly extracted from case–control studies or clinical trials in which such patients were not the primary objects of study. Clinical trials are usually short term; due to the heterogeneity of patient groups in observational studies, it is therefore difficult to make definitive conclusions.

Nevertheless, this recommendation was easily agreed upon because it is not uncommon to encounter patients presenting comorbidities, factors for poor prognosis or with secondary effects and in whom complete remission or low disease activity should not be the primary objective. Nonetheless, this does not mean that good results cannot also be achieved.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of InterestsRaimon Sanmartí is a member of the Advisory Council for Hospital Outpatient Medication Dispensation for the Catalonian Public Healthcare System (Catsalut). He has received: funding to attend courses and medical congresses from MSD, Abbvie, Roche and Pfizer; professional fees as a lecturer from MSD, Abbvie, Roche, Pfizer, UCB and Bristol; funding for educational programmes or courses from Bristol and MSD; funding for research participation from Roche; and consulting fees from MSD, Abbvie, Roche, Pfizer, UCB and Bristol.

Susana García declares no conflict of interests.

José María Álvaro-Gracia has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Pfizer and Roche; professional fees as a lecturer from BMS, Abbvie, MSD, Pfizer, UCB, Roche, Jansen-Cilag, Abbvie and Amgen; funding for research participation from UCB, Roche and Amgen; and consulting fees from BMS, Pfizer, UCB, Roche and Jansen-Cilag.

José Luis Andreu has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Pfizer, Abbvie, Gebro and Menarini; professional fees as a lecturer from Abbvie, GSK, Roche and UCB; and consulting fees from UCB and GSK.

Alejandro Balsa has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Roche, BMS, Pfizer, Abbvie and MSD; professional fees as a lecturer from Roche, BMS, Pfizer and Abbvie; funding for educational programmes or courses from Roche and Pfizer; funding for research participation from Pfizer; and consulting fees from Roche, BMS, Pfizer, Abbvie and MSD.

Rafael Cáliz has received funding to attend courses/medical congresses from MSD, Roche, Abbvie and Pfizer; and professional fees as a lecturer from BMS, Menarini, Roche, Pfizer and GSK.

Antonio Fernández-Nebro has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from MSD, Pfizer, BMS, Abbvie, Roche and Angen; professional fees as a lecturer from MSD, Pfizer, BMS, Abbvie and Roche; and consulting fees from MSD, Pfizer, BMS, Abbvie and Roche.

Iván Ferraz-Amaro has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Abbvie, MSD and Pfizer; and professional fees as a lecturer from Abbvie.

Juan Jesús Gómez-Reino has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Abbott, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB; professional fees as a lecturer from Abbott, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB; funding for educational programmes or courses from MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB; and consulting fees from Abbott, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB.

Isidoro González has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from MSD, Actelion, Abbvie and Pfizer; professional fees as a lecturer from UCB, Roche, Abbott and BMS; funding for research participation from Amgen and Tigenix; and consulting fees from Pfizer. He is also a stockholder in Zeltia.

Sara Marsal has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Pfizer and Roche; professional fees as a lecturer from BMS, Roche and UCB; funding for educational programmes or courses from Roche and UCB; funding for research participation from Roche; and consulting fees from Pfizer, Roche, UCB and BMS.

Emilio Martín-Mola has received professional fees as a lecturer from Pfizer, MSD, BMS and Abbott; and consulting fees from MSD, Pfizer, Celgene, Abbott and Roche.

Víctor Manuel Martínez-Taboada has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Abbott, Menarini and Pfizer; professional fees as a lecturer from Esteve, Abbott, Roche and UCB; funding for research participation from Roche, MSD, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, UCB and Pfizer; and consulting fees from UCB, Roche, Cellerix, Pfizer, Sobi, Servier and Hospira.

José Vicente Moreno Muelas has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Gebro, Pfizer and Abbvie.

Ana M. Ortiz has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Abbvie, Amgen, GSK, Lilly, Menarini, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB; professional fees as a lecturer from Abbvie, Esteve, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB; funding for research participation from Roche; and consulting fees from Abbvie.

Jesús Tornero has received funding to attend courses and medical congresses from Pfizer; professional fees as a lecturer from Gebro, Pfizer, FAES FARMA, UCB, Menarini and Grunenthal; and funding for research participation from Roche.

We would like to acknowledge the authors of the systematic reviews: Ana M. Ortiz, Miguel Ángel Abad, Claudia Alejandra Pereda, María Betina Nishishinya, Jesús Maese and Eugenio Chamizo. We would also like to thank Federico Díaz-González, Director of the SER Research Unit, for his contributions towards safeguarding the independent nature of this document, along with Mercedes Guerra, SER documentalist, and Daniel Seoane, SER methodologist.

Please cite this article as: Sanmartí R, García-Rodríguez S, Álvaro-Gracia JM, Andreu JL, Balsa A, Cáliz R, et al. Actualización 2014 del Documento de Consenso de la Sociedad Española de Reumatología sobre el uso de terapias biológicas en la artritis reumatoide. Reumatol Clin. 2015;11:279–294.