The aim of this study was to examine anxiety, depression, pain centralization, and pain catastrophization in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) and evaluate whether these factors are predictors of disease severity in FMS.

Patient and methodsDepression was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), anxiety with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), pain centralization with the Centrality of Pain Scale (COPS), pain catastrophization with the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), and FMS severity with the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ). Two separate hierarchical linear regression analyses were performed to determine whether there was a significant association between disease severity and the assessed psychosocial factors.

ResultsThe study was completed with a total of 48 FMS patients (mean age 49.54±8.28 years). FIQ score was moderately correlated with COPS score (rSpearman=0.670, p<0.001) and PCS score (rSpearman=0.663, p<0.001). In the logistic regression model, COPS and PCS scores were significant predictors of FIQ score. The predictive variables explained 43.7% of the variation in FIQ score.

ConclusionThis study showed that pain centralization and catastrophization can be considered indicators of disease severity in FMS. The results suggest that routine assessment of pain centralization and pain catastrophizing behaviors in individuals with FMS is needed and that cognitive behavioral therapy approaches may be beneficial in reducing disease severity.

El objetivo de este estudio fue examinar la ansiedad, la depresión, la centralización del dolor y la catastrofización del dolor en pacientes con síndrome de fibromialgia (FMS) y evaluar si estos factores son predictores de la gravedad de la enfermedad en el FMS.

Pacientes y métodosLa depresión se evaluó con el Inventario de Depresión de Beck (BDI), la ansiedad con el Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck (BAI), la centralización del dolor con la Escala de Centralidad del Dolor (COPS), la catastrofización del dolor con la Escala de Catastrofización del Dolor (PCS), y la gravedad del FMS con el Cuestionario de Impacto de la Fibromialgia (FIQ). Se realizaron dos análisis de regresión lineal jerárquica por separado para determinar si existía una asociación significativa entre la gravedad de la enfermedad y los factores psicosociales evaluados.

ResultadosEl estudio se completó con un total de 48 pacientes con FMS (edad media 49,54±8,28 años). La puntuación FIQ se correlacionó moderadamente con la puntuación COPS (rSpearman=0,670, p <0,001) y la puntuación PCS (rSpearman=0,663, p <0,001). En el modelo de regresión logística, las puntuaciones COPS y PCS fueron predictores significativos de la puntuación FIQ. Las variables predictivas explicaron el 43,7% de la variación en la puntuación del FIQ.

ConclusiónEste estudio mostró que la centralización del dolor y la catastrofización pueden considerarse indicadores de la gravedad de la enfermedad en el FMS. Los resultados sugieren que es necesaria una evaluación rutinaria de los comportamientos de centralización y catastrofización del dolor en individuos con FMS y que los enfoques de terapia cognitivo-conductual pueden ser beneficiosos para reducir la gravedad de la enfermedad.

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a musculoskeletal disease characterized by various symptoms, especially chronic widespread pain, sleep problems, fatigue, muscle/joint stiffness, and cognitive and psychiatric disorders.1 FMS is common in the general population, with a global prevalence of up to 2–3%.2 The etiology of FMS is not fully understood. However, it is thought that the interaction of genetic predisposition, stressors, and central and environmental mechanisms causes pain perception and nociplastic changes.3

People with FMS experience more psychological stress symptoms such as depression or anxiety compared to the general population and other chronic pain groups.4 Another common condition seen in FMS is pain catastrophization. This forms the cognitive infrastructure for chronification of pain, and is also a correlate of cognitive attention deficit.5 Studies have shown that pain catastrophizing is an important indicator of the presence of emotional disorders such as depression and anxiety and negatively affects treatment results.6

The multidimensional nature of FMS makes it difficult to define the disease and evaluate its severity.7 In previous studies, FMS severity has generally been assessed using the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ).7 The FIQ is a validated, disease-specific scale developed to capture the spectrum of FM-related symptoms and problems.8 However, there is need studies have examined the factors that predict FMS severity as assessed by the FIQ.

Popular pain models, such as the fear-avoidance and psychological pain model, describe a complex interaction between symptomatology and psychological mechanisms that leads to functional limitations in patients with chronic pain, such as individuals with FMS.9 Moreover, people with FMS feel more affected by their disease in their daily lives and have more maladaptive coping strategies compared to patients with other rheumatic diseases.10 Among coping strategies, individuals with FMS catastrophize pain more, and are less likely to use the skills of diverting attention or ignoring pain sensations.11 Taking all this into account, it is also very important to evaluate how centralized pain is in FMS and how patients’ lives are impacted by pain.12 We hypothesized that levels of anxiety, depression, pain centralization, and pain catastrophization may be markers of FMS severity. Thus, the aim of this study was to examine anxiety, depression, pain centralization, and pain catastrophization in individuals with FMS and evaluate whether these factors are predictors of disease severity.

Material and methodsThis descriptive, prospective, cross-sectional study was conducted between May and October 2024 in the physical therapy and rehabilitation center of Kutahya Health Sciences University Hospital. Participants who agreed to participate in the study signed an informed consent form. The study protocol was approved by the Kutahya Health Sciences University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (no: 2024/05-16) and carried out in accordance with the articles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

ParticipantsThe study included individuals diagnosed with FMS by a specialist (H.H.G.) according to the diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR).1

Inclusion criteria- •

Being at least 18 years of age,

- •

Being diagnosed with FMS according to the ACR diagnostic criteria,1

- •

Volunteering to participate in the study.

- •

Being male,

- •

Being diagnosed with any medical condition known to contribute to the symptomatology of FMS, such as thyroid disease, inflammatory arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, myositis, vasculitis, or Sjögren's syndrome,

- •

Being illiterate,

- •

Declining to participate in the study.

Data such as the participants’ age, height, weight, education level, and disease duration were recorded on a personal information form. The patients then completed self-report scales assessing depression, anxiety, pain centralization attitudes, pain catastrophization, and FMS severity.

AssessmentsDepressionThe participants’ depression levels were evaluated with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a scale developed by Beck et al.,13 in 1961 and revised in 1978 to measure the severity of depressive symptoms. The Turkish validity and reliability study was conducted by Hisli in 1989.14 Each of the 12 scale items consists of a self-evaluation statement with 4 response options scored from 0 to 3. A higher total score indicates a higher level or severity of depression. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale was found to be 0.80.14

AnxietyThe participants’ anxiety levels were evaluated with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). The BAI was developed by Beck et al. in 198815 and the Turkish validity and reliability study was conducted by Ulusoy et al. in 1998.16 The self-report measure evaluates the frequency of anxiety symptoms with 21 items scored between 0 and 3. The respondent rates to what extent the feeling of distress has bothered them in the last week. A high score indicates high anxiety. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale was reported to be 0.93.16

Pain centralizationThe participants’ levels of pain centralization, or the impact of pain on the participants, was evaluated with the Centrality of Pain Scale (COPS). The COPS was developed by Nicolaidis et al.,17 in 2011 to evaluate how participants perceive pain and how their lives are affected by pain. It is a 10-item scale in which items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores range from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating more centralized pain. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the scale was conducted by Unubol and Ulutatar,18 who reported a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.84.

Pain catastrophizationThe participants’ catastrophization of pain was evaluated with the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS). The PCS was developed by Sullivan et al.,19 to detect catastrophizing thoughts or feelings related to pain experienced by patients and ineffective coping strategies. The scale consists of 13 items and is scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0–4 points), for a total score ranging from 0 to 52 points. High scores indicate a high level of pain catastrophization. In the validity and reliability of the Turkish version, conducted by Uğurlu et al.,20 the Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale was found to be 0.95.

Disease severityThe Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) was used to determine the severity of the disease. The FIQ is a self-report scale developed by Burckhardt et al.10 that measures physical function, well-being, inability to work, difficulty at work, pain, tiredness, morning tiredness, stiffness, anxiety, and depression. Except for the item about feeling good, low scores indicate improvement or being less affected by the disease. The maximum score is 100, with higher scores indicating greater disease severity. The Turkish validity and reliability adaptation of the scale was conducted by Sarmer et al.,8 who reported a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.72.

Statistical analysisAll data analyses were performed with the SPSS package program, version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The normality of data distributions was examined using skewness and kurtosis. The results indicated that depression and anxiety scores; pain centralization and pain catastrophization scores and disease severity scores were normally distributed. The participants’ quantitative demographic data were expressed using means, standard deviations, and ranges, while categorical data were given as numbers (n) and percentages (%). Relationships between FIQ total score and depression, anxiety, pain centralization, and pain catastrophization scores were examined by Spearman correlation analysis. After checking for potential confounding variables, two separate hierarchical linear regression analyses were performed to determine whether the evaluated psychosocial factors were associated with disease severity. Before conducting regression analysis, the data were checked to ensure they met the necessary assumptions. In the first step of these models, demographic characteristics such as age, body mass index, education level, and pain duration were checked (all of these variables were entered into the model). Data screening procedures revealed significant correlations between measures of depression, anxiety, pain centralization, and pain catastrophization. As a result, a stepwise regression analysis was performed for the variables of depression, anxiety, pain centralization, and pain catastrophization scores.21

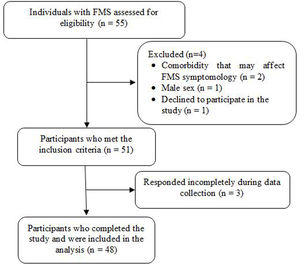

ResultsOf 55 individuals with FMS evaluated for eligibility, 2 were excluded because they had a comorbidity that could affect FMS symptomology, 1 was excluded because they were male, and 1 declined to participate in the study. Therefore, the study was completed with a total of 48 individuals with FMS who met the inclusion criteria and completed the assessments (Fig. 1). The participants’ mean age was 49.54±8.28 years and their mean disease duration was 4.96±3.29 years. The mean disease severity score of the participants according to the FIQ was 52.38±14.75. The participants mean scores were 17.70±12.01 on the BDI, 25.20±13.16 on the BAI, 32.76±10.42 on the COPS, and 30.64±12.74 on the PCS. Detailed information about the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants is shown in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

| n (%) | Mean±SD | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.54±8.28 | 30–66 |

| Height (cm) | 159.81±5.65 | 174–150 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.18±11.56 | 52–96 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.50±5.43 | 19–40.28 |

| Education level | ||

| Elementary school | 30 (62.50%) | |

| High school | 13 (27.08%) | |

| University | 5 (10.42%) | |

| Disease duration (years) | 4.96±3.29 | 1–20 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 17.70±12.01 | 1–42 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 25.20±13.16 | 3–53 |

| Centrality of Pain Scale | 32.76±10.42 | 7–52 |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale | 30.64±12.74 | 1–55 |

| Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire | 52.38±14.75 | 12–73 |

n: number of people, %: percentage, SD: standard deviation.

When the relationship between disease severity and psychosocial factors was examined, FIQ score was found to be moderately correlated with BDI score (rSpearman=0.433, p=0.002) and weakly correlated with BAI score (rSpearman=0.383, p=0.006). FIQ score was also moderately correlated with COPS score (rSpearman=0.670, p<0.001) and PCS score (rSpearman=0.663, p<0.001) (Table 2).

Correlations between Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire score and psychosocial factors.

| Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 0.433* | 0.002 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 0.383* | 0.006 |

| Centrality of Pain Scale | 0.670* | <0.001 |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale | 0.663* | <0.001 |

r=correlation coefficient, p: significance level.

Regression analysis to determine the association of BDI, BAI, COPS, and PCS scores with FIQ score showed that PCS and COPS scores were positive predictors of FIQ score. In the regression model, it was observed that 43.7% of the variation in FIQ score was explained by the predictive variables (Table 3).

Predictors of disease severity in stepwise regression analysis.

| R | R2 | Adj. R2 | F | β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.721 | 0.520 | 0.437 | 39.016 | ||||

| Centrality of Pain Scale | 0.402 | 0.214 | 2.803 | 0.007 | ||||

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale | 0.378 | 0.175 | 2.639 | 0.011 |

F: significance of the model, β: standardized constant, SE: standard error, t: test value, p: significance value, Adj R2: proportion of the variance in the dependent variable explained by independent variables.

The results of this study showed that depression, anxiety, pain centralization, and pain catastrophization were significantly associated with FMS symptomology and severity as measured by the FIQ. In addition, this study revealed that pain centralization and pain catastrophization can be considered indicators of disease severity in FMS.

Previous studies clearly demonstrated that anxiety and depression are associated with pain perception and negatively affect health-related quality of life in FMS.22–24 Higher levels of pain catastrophization have also been associated with increased pain and pain-related disability in FMS.25,26 Similarly, Galvez-Sanchez et al. showed that catastrophizing pain may be an important determinant of health-related quality of life in individuals with FMS.22 Consistent with previous studies, our results showed that high levels of anxiety, depression, and pain catastrophization may cause more severe symptoms in FMS, and that catastrophizing pain may also be an indicator of disease severity/symptomology. As catastrophizing pain directs attention to the threatening stimuli,27 it may exacerbate symptoms and heighten disease perception in individuals with FMS.

Pain catastrophization is associated with various cognitive biases that can propagate a maladaptive state of apprehension in the patient.28 These biases may involve exaggerating the importance of certain negative feelings or symptoms, selective attention to negative elements (ignoring positive elements), overgeneralizing the consequences of a negative event, cognitions of helplessness and loss of control, and a generally pessimistic orientation.29 Other relevant factors may include body hypervigilance and somatosensory amplification, which can increase pain perception.30,31 Likewise, negative affectivity, susceptibility to stress and negative appraisal, and hypervigilance biases may be factors associated with central sensitivity to pain, one of the more widely accepted hypotheses regarding the pathophysiology of FMS.32–35

“Pain centrality” is a term used to describe a patient-centered concept of how central pain is in a person's life (i.e., how much it dominates or takes over their life).36 There may be a mismatch between traditional pain measures and patient or clinician assessment,37 as many assessment methods cannot measure to what extent pain dominates a patient's life or explain how well they are doing in general. In this respect, it has been reported that the PCS can explain how well patients are overall, and it may even be associated with disease severity, quality of life, sleep problems, and depression in individuals with FMS.12 Similarly, the results of this study showed that pain centralization may be an indicator of disease severity.

In clinical practice, routinely assessing different aspects of FMS, such as catastrophizing and centralizing pain, can help healthcare providers recognize possibly maladaptive coping strategies. Furthermore, reductions in pain catastrophization and centralization scores can be used in the clinic as indicators when evaluating the effectiveness of treatment strategies. For clinicians, evaluating these two factors in detail as part of treatment strategies and integrating hands-off approaches such as physiology-informed physiotherapy into the treatment programs of patients with high scores may be considered as promising methods that may increase treatment success in individuals with FMS.38,39 However, more research on this subject is needed.

This study has certain limitations. The main limitations of the study are its cross-sectional design, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions regarding causation, and the relatively small sample size for regression analysis. In addition, the analysis is largely based on self-report measures. These data are susceptible to bias because of factors such as the participants’ moods.

ConclusionThis study showed that pain centralization and catastrophization can be considered indicators of disease severity in FMS. The findings suggest the need for routine assessment of pain centralization and pain catastrophizing behaviors in individuals with FMS and the potential benefit of cognitive behavioral therapy approaches to reduce disease severity.

Authors’ contributionsIsmail Saracoglu and Hasan Huseyin Gokpinar contributed to conception and design analysis and interpretation of data, drafting, and revision of the article. Cihan Caner Aksoy contributed to conception and design, interpretation of data, and revision of the article. Muhammed Fatih Ozdemir contributed to analysis and assembly of data, interpretation of data and revision of the article.

FundingThere is nothing to declare.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.