Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystemic autoimmune disease that particularly affects young women during their second and third decades. Events attributed to SLE itself and others related to the disease may impact negatively on the quality of life, employment and disability. However, there are not many studies focused on the impact that the disease may have on patients regarding those aspects. In Spain, the evaluation of disability and the assignation of a pension is given by the National Social Security Institute of Spain, INSS (“Instituto Nacional de la Seguridad Social”).

ObjectiveTo assess the relationship between cumulative damage regarding the affected organ and the percentage of disability recognised by the National Social Security Institute of Spain (INSS) in SLE patients.

MethodsCross-sectional prospective study of SLE patients according to the SLICC-2012 criteria, from the Rheumatology Service of two Spanish hospitals. We collected clinical and demographic data through personal interview and the SLICC/ACR questionnaire, and classified patients regarding a recognised disability or not.

Results142 patients were evaluated; 30% had some percentage of official disability. We found a positive correlation between percentage of recognised disability and the SLICC/ACR index score. Musculoskeletal system is the most affected system, without differences between both groups; but we found a higher proportion of damage in nervous system, renal and vasculitis in patients with a recognised disability.

ConclusionThere is a positive correlation between percentage of recognised disability in Spain and the cumulative damage in SLE.

El lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) es una enfermedad multisistémica autoinmune que afecta especialmente a las mujeres jóvenes durante su segunda y tercera décadas. Los eventos atribuidos al propio LES y otros relacionados con la enfermedad pueden tener un impacto negativo en la calidad de vida, el empleo y la discapacidad. Sin embargo, existen pocos datos publicados al respecto. En España, la evaluación de la discapacidad y la asignación de una pensión corresponden al Instituto Nacional de Seguridad Social de España (INSS).

ObjetivoEvaluar la relación entre el daño acumulado relacionado con el órgano afectado y el porcentaje de discapacidad reconocido por el INSS en pacientes con LES.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo transversal de pacientes con LES según los criterios SLICC-2012, del servicio de reumatología de 2 hospitales de España. Recopilamos datos clínicos y demográficos mediante entrevista personal y el cuestionario SLICC/ACR, y clasificamos a los pacientes con respecto a una discapacidad reconocida o no.

ResultadosSe evaluaron 142 pacientes; el 30% tenía algún porcentaje de discapacidad oficial. Encontramos una correlación positiva entre el porcentaje de discapacidad reconocida y la puntuación del índice SLICC/ACR. El sistema musculoesquelético es el sistema más afectado, sin diferencias entre ambos grupos; pero encontramos una mayor proporción de daño en el sistema nervioso, renal y vasculitis en pacientes con una discapacidad reconocida.

ConclusiónExiste una correlación positiva entre el porcentaje de discapacidad reconocida en España y el daño acumulado en el LES.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystemic autoimmune disease that particularly affects young women during their second and third decades. In Spain, according to the EPISER1 population study (Estudio de Prevalencia e Impacto de las enfermedades reumáticas en la población adulta española, de la Sociedad Española de Reumatología), SLE prevalence is estimated at 9 per 10,000 inhabitants, although in Europe it is estimated at around 50 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.2 According to Spanish national registries, between 5 and 10 new cases per 100,000 people are detected each year.3,4

Events attributed to SLE itself and others related to the disease may impact negatively on the quality of life, employment and disability of those affected. However, there are not many studies focused on the impact that the disease may have on patients regarding those aspects. For example, in 2013 a Slovakian cohort showed that 63% of SLE patients were registered disabled and receiving some kind of pension,5 whereas in 2018 a Finnish cohort revealed that 6% of SLE workers needed a work disability authorisation in a 5 year follow-up study.6

The latest report on disability data in Spain, the “Olivenza Report” (El Informe Olivenza), edited by the State Disability Observatory and promoted by the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality, was published in 2017. This report states that in Spain there are 1,774,800 people with recognised disabilities between the ages of 16 and 64, representing 5.9% of the active age population. Focusing on our region, it shows that 3.2% of the general population have a recognised disability, representing 6% of the total country.7 The assessment of this situation is regulated by Royal Decree (RD) 1971/1999, of December 23, on the procedure for the recognition, declaration and qualification of the degree of disability.8 It gives the responsibility for the determination of the degree of disability to technical teams called Assessment and Guidance Teams (in Spanish Equipos de Valoración y Orientación: EVO) which are formed by, at least, one doctor, one psychologist and one social worker. They issue a proposed opinion that must necessarily contain the diagnosis, type and degree of the disability and, where appropriate, the scale scores to determine the need for help from another person and the existence of mobility difficulties to use public transport. The 33% of disability that gives the right to the recognition of the condition of a “person with disability”.9

Finally, the evaluation and certification of disability and the assignation of a pension, if applicable, is given by the National Social Security Institute of Spain, INSS (Instituto Nacional de la Seguridad Social). This certificate is the administrative recognition of disability and its purpose is to compensate for the social disadvantages that disability implies by providing access to rights and benefits of different types, with a view to providing equal opportunities. The rating of the degree of disability relates to unified technical criteria, set by the scales described in Annex I of the aforementioned Royal Decree, and will be subject to assessment of both the disabilities presented by the person, and, where appropriate, the relative social factors, among others, to their family environment and employment, educational and cultural situation, which hinder their social integration. The degree of disability will be expressed as a percentage, through the application of the scales indicated in Section (A) of the aforementioned annex.9 We therefore attempted to assess the relationship between cumulative damage regarding the affected organ and the percentage of disability recognised by the INSS in SLE patients in two Spanish hospitals of this region. In addition, we describe the employment profile between SLE patients in our cohort. It is to be noted that this is a post hoc study, not being the main objective of our initial study.

MethodsWe performed a cross-sectional prospective study of SLE patients according to the 2012 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC-2012) criteria,10 from the Rheumatology Service of two Spanish hospitals. We collected clinical and demographic data through personal interview and the SLICC/ACR questionnaire, and used a tailor-made survey to classify patients regarding a recognised disability or not, as well as their actual job.

Study participantsBetween 2014 and 2015, we recruited 142 patients who met the SLICC-2012 criteria for the classification of SLE, and 34 healthy subjects. Patients were monitored at the Rheumatology Department two Spanish hospitals. All subjects underwent a complete medical examination upon enrollment, and cumulative clinical manifestations were reflected as defined in the RELESSER study11 (REgistro de Lupus Eritematoso Sistémico de la Sociedad Española de Reumatología). Our study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent was obtained from both patients and healthy subjects. The study had previously been approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the hospital. The data was stored in an electronic and secure database. However, we only had registered data for employability in 130 patients, and for official pensions in 140 patients.

Clinical featuresWe arranged one additional visit to assess the study. Each patient underwent a clinical and analytical evaluation, as well as a review of their clinical history focused mainly on SLE and related pathologies.

Regarding SLE, data was collected through personal interviews with the patients and from their clinical history, particularly focusing on the debut date and initial manifestations, previous and current treatments and general state of the disease according to the patient using a visual analog scale (VAS), where 0 meant “very good” and 10 “very bad”.

QuestionnairesTo assess chronic impairment in patients, the SLICC/ACR (Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology) index was employed. It is used to measure the accumulated damage in SLE, defined as irreversible change, but not related to active inflammation, occurring from the diagnosis of the disease, confirmed by clinical evaluation and present for ≥6 months unless otherwise indicated.12

For the disability percentage, we used a tailor-made survey designed for this purpose. We asked subjects (both patients and healthy control subjects) if they had any official degree of disability, the options being ‘yes’ or ‘no’. If an affirmative response was given, the percentage was asked. Regarding work profiles, we asked patients some simple questions to gather information about employment/unemployment, retirement and if they were receiving any pension.

Statistical analysisAs this is an observational and descriptive substudy, it only reflects the prevalence of disability and employability in our group of patients, allowing us to estimate this fact. Likewise, we analysed by organs or systems affected, and tried to find any association with the official given disability.

ResultsDemographic characteristicsIn our group of 142 patients, which had a clear majority of female participants (94.4%), the average age at SLE diagnosis was 33.29 (13.53) years, and the mean age at the time of visit was 49.13 (12.84) years, with a mean of 15.83 (10.56) years of disease duration. Regarding race, 94% of the patients were Caucasian, 5% were Hispanic and <1% were Indian. Patients were receiving medication as follows: 55% hydroxychloroquine, 53.52% corticosteroids, 18.3% azathioprine, 18.3% methotrexate, 7.75% mycophenolate mofetil, 6.35% biological agents and 0.7% cyclophosphamide. In addition, 40.85% were on aspirin and 10.56% on anticoagulants.

Clinical featuresIn our series, 30% of SLE patients had some percentage of official disability; however, none of the healthy control subjects had an official disability recognised by the INSS. Regarding cumulative damage, the mean SLICC/ACR was 1.06±1.42, and 57% of our patients ticked 4 or less on the VAS scale.

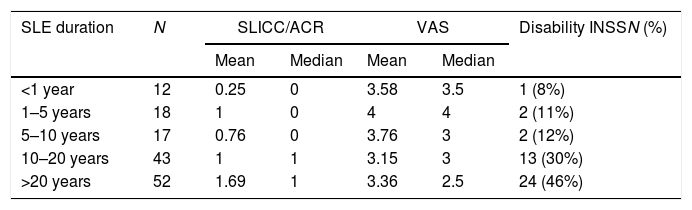

In order to synthesise results, we first classified patients depending on SLE duration: less than 1 year, between 1 and 5 years, between 5 and 10 years, between 10 and 20 years and more than 20 years. Results of the SLICC/ACR questionnaire, VAS scale and official disability are shown in Table 1.

Cumulative damage regarding SLICC/ACR and SLE evolution. Relation to VAS scale and official disability.

| SLE duration | N | SLICC/ACR | VAS | Disability INSSN (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | |||

| <1 year | 12 | 0.25 | 0 | 3.58 | 3.5 | 1 (8%) |

| 1–5 years | 18 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 (11%) |

| 5–10 years | 17 | 0.76 | 0 | 3.76 | 3 | 2 (12%) |

| 10–20 years | 43 | 1 | 1 | 3.15 | 3 | 13 (30%) |

| >20 years | 52 | 1.69 | 1 | 3.36 | 2.5 | 24 (46%) |

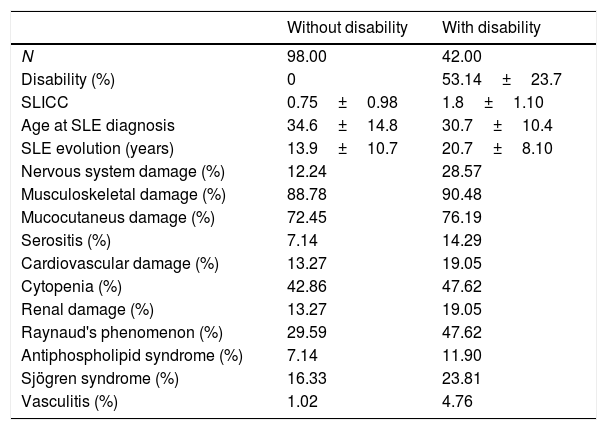

Finally, we analysed a possible association between cumulative damage according to the affected organ and official disability, classifying patients depending on whether they had an official disability or not. We found a positive correlation between the percentage of recognised disability and the SLICC/ACR index score. The musculoskeletal system is the most affected in general, without differences between either groups. However, we found a greater involvement of the nervous system, serous, renal and vasculitis in patients with disabilities. The clinical characteristics of each group regarding SLICC/ACR results are summarised in Table 2. In addition, the longer the SLE evolution, the greater the proportion of patients with a recognised disability, and the greater its degree, albeit varying from 33% to 100%.

SLE patients description regarding SLICC/ACR index and disability.

| Without disability | With disability | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 98.00 | 42.00 |

| Disability (%) | 0 | 53.14±23.7 |

| SLICC | 0.75±0.98 | 1.8±1.10 |

| Age at SLE diagnosis | 34.6±14.8 | 30.7±10.4 |

| SLE evolution (years) | 13.9±10.7 | 20.7±8.10 |

| Nervous system damage (%) | 12.24 | 28.57 |

| Musculoskeletal damage (%) | 88.78 | 90.48 |

| Mucocutaneus damage (%) | 72.45 | 76.19 |

| Serositis (%) | 7.14 | 14.29 |

| Cardiovascular damage (%) | 13.27 | 19.05 |

| Cytopenia (%) | 42.86 | 47.62 |

| Renal damage (%) | 13.27 | 19.05 |

| Raynaud's phenomenon (%) | 29.59 | 47.62 |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome (%) | 7.14 | 11.90 |

| Sjögren syndrome (%) | 16.33 | 23.81 |

| Vasculitis (%) | 1.02 | 4.76 |

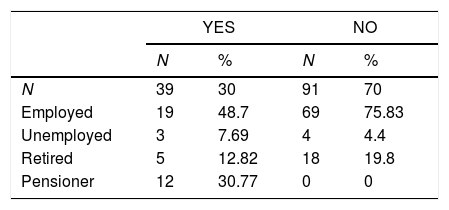

Concerning the work profile, we had data from just 130 patients; in this order, we used the previous classification depending on whether they had a disability or not, and took note of their laboural state. Results are reflected in Table 3. Among those who were employed, professions were very varied, without there being any correlation.

DiscussionThe patient profile in our series is that of a young woman, who debuted with SLE at around 30 years of age, and who at the time of the visit has an average age of 50 years, with 15 years of disease evolution. The figures are similar in both sexes. This data corresponds to that published in other series, both national and international.2,3,11 Regarding the ethnic characteristics, given the circumstances of our location, we could not assess the existence of different interracial patterns, due to the low rate of non-Caucasians in the areas of influence of both hospitals; therefore, the data of this study could not be extrapolated to patients of other races.

Focusing on disability and the work profile, we could only analyse this data in 130 patients. Of these, 30% had experienced some degree of disability, on the understanding that we refer to people with a degree of disability greater than or equal to 33% and assimilated according to Legislative RD 1/2013. This means that the proportion of disabled people is multiplied by a factor of 10 between SLE patients, with respect to the total circumstances that are taken into account to give an official measure of disability, in our region.7 However compared to the Slovakian cohort, it doubles the percentage of SLE patients registered as disabled (63%).5 But in Spain, we have the same rate as the Finnish cohort.6 In this last report, we found that in Finland SLE itself is enough for a disability ranking, unlike Spain. In Spain, SLE itself is not recognised as a disabling disease by the National Health System. Here in Spain, the degree of disability is assessed depending on how the disease affects the worker and their ability to work. In light of this data, it could be interesting to carry out a more detailed analysis regarding the occupational profile of SLE patients as well as the disability they present.

Within our group of disabled SLE patients, 48.7% were active, 7.69% were unemployed, 12.82% were retired and 30.77% were receiving a full disability pension, and in Spain this last circumstance means they are no longer working. This data is difficult to compare with the Slovakian cohort, since profiles of disability are different5; nor to the Finnish cohort, since they studied an early-onset SLE group.6 However, compared to the Spanish data, the musculoskeletal system is the most affected both in SLE patients and in those of the general population with an official disability, which matches our own results.7 This contrasts with the fact that between disabled SLE patients, there is a higher proportion of major organs affected than in non-disabled SLE patients.

Regarding cumulative damage, we observed that the longer the disease progressed, the greater its impairment was according to the scores of the SLICC/ACR questionnaire, a fact that seems logical on the basis that lupus affects patients in an organ-specific way. It is striking that the perception of the quality of life of our sample does not correlate with the accumulated damage caused by the disease; then we see that the deterioration of an organ or system does not necessarily diminish the quality of life of our patients. Therefore, the perception of the general state of our patients does not appear to depend on the time of evolution of the disease, nor on the accumulated damage caused by it. However, there is a positive correlation in the trinomial time of evolution-disability-degree of disability, since a greater evolution relates to a greater disability and to a greater degree. In terms of disease self-perception we used a VAS scale. The mean in our patients was 3.55 with a median of 3, which indicates a good or very good assessment of the state of their disease. 57% of our sample scored 4 points or less on the scale. Overall, patients have a very low degree of accumulated damage, and also the general state perceived by patients is good, regardless of the time of disease progression.

ConclusionsThere is a positive correlation between the percentage of recognised disability in Spain and the cumulative damage in SLE. There are no unified criteria for disability recognition or what it implies between countries. Further studies would give a broader profile of disability in SLE patients.

Ethics approvalAll procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

FundingThis study was funded by Generalitat Valenciana (grant number GV15/83).

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

We are thankful to David Hervás and Victoria Fornés from Biostatistic Unit IIS La Fe, to Dr Raquel Amigo from the Biobanco La Fe from the HUP La Fe and to Mª Jesús Baeza from the Arnau de Vilanova Hospital library, for their help with this study. Also to Barbara Richmond-O’Neill, for helping with the language style.

The authors would like to give special thanks to all SLE patients and healthy volunteers for their altruistic participation in this study.